At the University of Edinburgh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

272 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

272 bus time schedule & line map 272 Banff Low Street - Fraserburgh Bus Station View In Website Mode The 272 bus line (Banff Low Street - Fraserburgh Bus Station) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Banff: 10:02 AM - 12:02 PM (2) Fraserburgh: 10:57 AM - 2:57 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 272 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 272 bus arriving. Direction: Banff 272 bus Time Schedule 39 stops Banff Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 10:02 AM - 12:02 PM Bus Station, Fraserburgh Hanover Street, Fraserburgh Tuesday 10:02 AM - 12:02 PM Commerce Street, Fraserburgh Wednesday 10:02 AM - 12:02 PM King Edward Street, Fraserburgh Thursday 10:02 AM - 12:02 PM King Edward Street, Fraserburgh Friday 10:02 AM - 12:02 PM Alexandra Terrace, Fraserburgh Saturday Not Operational Crimond Court, Fraserburgh Corbie Drive, Fraserburgh Strichen Road, Fraserburgh 272 bus Info Direction: Banff Buchan Road, Fraserburgh Stops: 39 Strichen Road, Fraserburgh Trip Duration: 55 min Line Summary: Bus Station, Fraserburgh, Commerce Boothby Road, Fraserburgh Street, Fraserburgh, King Edward Street, Fraserburgh, Alexandra Terrace, Fraserburgh, Crossroads, Memsie Crimond Court, Fraserburgh, Corbie Drive, Fraserburgh, Buchan Road, Fraserburgh, Boothby Techmuiry Schoolhouse, Memsie Road, Fraserburgh, Crossroads, Memsie, Techmuiry Schoolhouse, Memsie, Whitestripe, Strichen, Bridge Whitestripe, Strichen Street, Strichen, Town Hall, Strichen, White Ship Court, Strichen, Library Gardens, Strichen, -

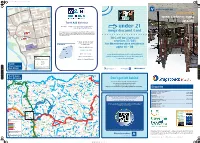

Don't Get Left Behind Turriff Public Transport Guide August 2017

Turriff side 1 Aug 2017.pdf 1 20/07/2017 13:13 ST M 2017 August CHURCH A R E K AC RD E D RR NFIEL E T R T CO NE TO S S Guide Transport Public D T GLA 24 B90 47 A9 T TREE P S Turriff FIFE STREET DUFF P Turriff A2B dial-a-bus M A ST I MANSE N S ET Mondays - Fridays: First pick up from 0930 hours T STRE R L P HAPE Last drop off by 1430 hours E C C A E S T T L E H A2B is a door-to-door dial-a-bus service operating in Turriff and outlying I L areas. The service is open to people who have difficulty walking, those L with other disabilities and residents who do not live near or have access PO B to a regular bus route. HIGH REET STR E S T EET ELLI A BALM All trips require to be pre-booked. OAD ON R CLIFT Simply call our booking line to request a trip. Turriff Academy Contact the A2B office on: Q ACE U RR IA T E EE R VICTO N ’ 01467 535 333 S P R O A D Option 1 for Bookings www.aberdeenshire.gov.uk/roads-and-travel/ Option 2 for Cancellations public-transport/under-21-mega-discount-card/ Key or call us 01467 533080 Route served by bus Option 3 for General Enquiries Bus Stop P Car Parking Turriff PO Post Office C Town Centre Created using Ordnance Survey OpenData A M 9 ©Crown Copyright 2016 Bus Stops 4 7 Y CM MY CY Pittulie Sandhaven Fraserburgh CMY Turriff Area Rosehearty K Bus Network Peathill 253 Don’t get left behind Pennan Whitehills Percyhorner Macduff Crovie Banff Gardenstown To receive advanced notification of changes to Auds Coburty bus services in Aberdeenshire by email, Boyndie 35/35A Greenskares Towie Mid Ardlaw A98 Silverford A90(T) sign up for our free alert service at Dubford New Gowanhill Longmanhill Aberdour https://online.aberdeenshire.gov.uk/Apps/publictransportstatus/ 35/35A Dounepark Cushnie Boyndlie Tyrie Memsie Enquiries To Elgin Mid Culbeuchly A97 Whitewell A98 Ladysford A98 Rathen Union Square Bus Station All Enquiries Kirktown Minnonie of Alvah 0800-1845 (Monday to Friday)............................................................................ -

Scottish Samurai Trail the Story of Thomas Blake Glover

Scottish Samurai Trail The story of Thomas Blake Glover #aberdeentrails Model of Jho Sho Maru #aberdeentrails Much has been written about the life and times of Thomas Blake Glover, and many myths have grown up around him. This guide has been produced to introduce his story and to inspire you to learn more about the era, the man, and some of places associated with him. Thomas’s links with Japan, and the changes that country went through in the latter half 19th century are rightly celebrated there, and his home in Nagasaki is Above: Thomas Blake Glover wearing the Order of the Rising Sun preserved as a museum, in extensive parkland known as Glover Garden. Courtesy Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture Both Aberdeen and Fraserburgh have connections to Glover and this trail guide covers both locations. Enjoy discovering about Thomas, his early life Cover: Thomas Blake Glover Courtesy Glover Garden in Scotland, and finding out about our connections to Japan! Accessibility This trail is accessible but has occasional steep parts / uneven ground. Picture Credits Transport All images © Aberdeen City Council unless otherwise stated. The historical images in the first section are courtesy First Bus 20 runs through Old Aberdeen to Don Street near Brig O’ Balgownie. Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture First Bus 15 runs to Footdee, returning by York Street. First Bus 1 & 2 run to Bridge of Don via King Street and Ellon Road. Images at 3 & 4: Courtesy of Aberdeen City Libraries/Silver City Vault All services go to/from Union Street. www.silvercityvault.org.uk Stagecoach 67/68 runs between Fraserburgh and Aberdeen Bus Station via King Street and Ellon Road. -

ADDRESSING CONCERNS RAISED by RSPB SCOTLAND .88 27 Addressing Concerns Raised by RSPB Scotland

Annex B - Appropriate Assessment – Moray West Offshore Wind Farm T: +44 (0)300 244 5046 E: [email protected] SCOTTISH MINISTERS ASSESSMENT OF THE PROJECT’S IMPLICATIONS FOR DESIGNATED SPECIAL AREAS OF CONSERVATION (“SAC”), SPECIAL PROTECTION AREAS (“SPA”) AND PROPOSED SPECIAL PROTECTION AREAS (“pSPA”) IN VIEW OF THE SITES’ CONSERVATION OBJECTIVES APPLICATION FOR CONSENT UNDER SECTION 36 OF THE ELECTRICITY ACT 1989 (AS AMENDED) AND FOR MARINE LICENCES UNDER THE MARINE (SCOTLAND) ACT 2010 AND MARINE AND COASTAL ACCESS ACT 2009 FOR THE CONSTRUCTION AND OPERATION OF THE MORAY WEST OFFSHORE WIND FARM AND ASSOCIATED OFFSHORE TRANSMISSION INFRASTRUCTURE SITE DETAILS: MORAY WEST OFFSHORE WIND FARM AND EXPORT CABLE CORRIDOR BOUNDARY – APPROXIMATELY 22.5KM EAST OF THE CAITHNESS COASTLINE IN THE OUTER MORAY FIRTH Name Assessor or Approver Date Fiona Mackintosh Assessor 15 April 2019 Ross Culloch Assessor 15 April 2019 Tom Evans Assessor 15 April 2019 Gayle Holland Approver 26 April 2019 Annex B - Appropriate Assessment – Moray West Offshore Wind Farm TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1: BACKGROUND ..................................................................................... 2 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 2 2 Appropriate assessment (“AA”) conclusion ................................................................ 2 3 Background to including assessment of proposed SPAs ........................................... 3 4 Details of proposed operation -

List of Consultees and Issues.Xlsx

Name / Organisation Issue Mr Ian Adams Climate change Policy C1 Using resources in buildings Mr Ian Adams Shaping Formartine Newburgh Mr Iain Adams Natural Heritage and Landscape Policy E2 Landscape Mr Ian Adams Shaping Formartine Newburgh Mr Michael Adams Natural Heritage and Landscape Policy E2 Landscape Ms Melissa Adams Shaping Marr Banchory Ms Faye‐Marie Adams Shaping Garioch Blackburn Mr Iain Adams Shaping Marr Banchory Michael Adams Natural Heritage and Landscape Policy E2 Landscape Ms Melissa Adams Natural Heritage and Landscape Policy E2 Landscape Mr Michael Adams Shaping Marr Banchory Mr John Agnew Shaping Kincardine and Mearns Stonehaven Mr John Agnew Shaping Kincardine and Mearns Stonehaven Ms Ruth Allan Shaping Banff and Buchan Cairnbulg and Inverallochy Ruth Allan Shaping Banff and Buchan Cairnbulg and Inverallochy Mrs Susannah Almeida Shaping Banff and Buchan Banff Ms Linda Alves Shaping Buchan Hatton Mrs Michelle Anderson Shaping Kincardine and Mearns Luthermuir Mr Murdoch Anderson Shaping Kincardine and Mearns Luthermuir Mrs Janette Anderson Shaping Kincardine and Mearns Luthermuir Miss Hazel Anderson Shaping Kincardine and Mearns Luthermuir J Angus Shaping Banff and Buchan Cairnbulg and Inverallochy Mrs Eeva‐Kaisa Arter Shaping Kincardine and Mearns Mill of Uras Mrs Eeva‐Kaisa Arter Shaping Kincardine and Mearns Mill of Uras Mr Robert Bain Shaping Garioch Kemnay K Baird Shaping Banff and Buchan Cairnbulg and Inverallochy Rachel Banks Shaping Formartine Balmedie Mrs Valerie Banks Shaping Formartine Balmedie Valerie Banks -

The Dalradian Rocks of the North-East Grampian Highlands of Scotland

Revised Manuscript 8/7/12 Click here to view linked References 1 2 3 4 5 The Dalradian rocks of the north-east Grampian 6 7 Highlands of Scotland 8 9 D. Stephenson, J.R. Mendum, D.J. Fettes, C.G. Smith, D. Gould, 10 11 P.W.G. Tanner and R.A. Smith 12 13 * David Stephenson British Geological Survey, Murchison House, 14 West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA. 15 [email protected] 16 0131 650 0323 17 John R. Mendum British Geological Survey, Murchison House, West 18 Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA. 19 Douglas J. Fettes British Geological Survey, Murchison House, West 20 Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA. 21 C. Graham Smith Border Geo-Science, 1 Caplaw Way, Penicuik, 22 Midlothian EH26 9JE; formerly British Geological Survey, Edinburgh. 23 David Gould formerly British Geological Survey, Edinburgh. 24 P.W. Geoff Tanner Department of Geographical and Earth Sciences, 25 University of Glasgow, Gregory Building, Lilybank Gardens, Glasgow 26 27 G12 8QQ. 28 Richard A. Smith formerly British Geological Survey, Edinburgh. 29 30 * Corresponding author 31 32 Keywords: 33 Geological Conservation Review 34 North-east Grampian Highlands 35 Dalradian Supergroup 36 Lithostratigraphy 37 Structural geology 38 Metamorphism 39 40 41 ABSTRACT 42 43 The North-east Grampian Highlands, as described here, are bounded 44 to the north-west by the Grampian Group outcrop of the Northern 45 Grampian Highlands and to the south by the Southern Highland Group 46 outcrop in the Highland Border region. The Dalradian succession 47 therefore encompasses the whole of the Appin and Argyll groups, but 48 also includes an extensive outlier of Southern Highland Group 49 strata in the north of the region. -

Banffshire and Buchan Coast Polling Scheme

Polling Station Number Constituency Polling Place Name Polling Place Address Polling District Code Ballot Box Number Eligible electors Vote in person Vote by post BBC01 Banffshire and Buchan Coast DESTINY CHURCH AND COMMUNITY HALL THE SQUARE, PORTSOY, BANFF, AB45 2NX BB0101 BBC01 1342 987 355 BBC02 Banffshire and Buchan Coast FORDYCE COMMUNITY HALL EAST CHURCH STREET, FORDYCE, BANFF, AB45 2SL BB0102 BBC02 642 471 171 BBC03 Banffshire and Buchan Coast WHITEHILLS PUBLIC HALL 4 REIDHAVEN STREET, WHITEHILLS, BANFF, AB45 2NJ BB0103 BBC03 1239 1005 234 BBC04 Banffshire and Buchan Coast ST MARY'S HALL BANFF PARISH CHURCH, HIGH STREET, BANFF, AB45 1AE BBC04 BBC05 Banffshire and Buchan Coast ST MARY'S HALL BANFF PARISH CHURCH, HIGH STREET, BANFF, AB45 1AE BBC05 BBC06 Banffshire and Buchan Coast ST MARY'S HALL BANFF PARISH CHURCH, HIGH STREET, BANFF, AB45 1AE BB0104 BBC06 3230 2478 752 BBC07 Banffshire and Buchan Coast WRI HALL HILTON HILTON CROSSROADS, BANFF, AB45 3AQ BB0105 BBC07 376 292 84 BBC08 Banffshire and Buchan Coast ALVAH PARISH HALL LINHEAD, ALVAH, BANFF, AB45 3XB BB0106 BBC08 188 141 47 BBC09 Banffshire and Buchan Coast HAY MEMORIAL HALL 19 MID STREET, CORNHILL, BANFF, AB45 2ES BB0107 BBC09 214 169 45 BBC10 Banffshire and Buchan Coast ABERCHIRDER COMMUNITY PAVILION PARKVIEW, ABERCHIRDER, AB54 7SW BBC10 BBC11 Banffshire and Buchan Coast ABERCHIRDER COMMUNITY PAVILION PARKVIEW, ABERCHIRDER, AB54 7SW BB0108 BBC11 1466 1163 303 BBC12 Banffshire and Buchan Coast FORGLEN PARISH CHURCH HALL FORGLEN, TURRIFF, AB53 4JL BB0109 BBC12 250 216 34 -

271 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

271 bus time schedule & line map 271 Fraserburgh View In Website Mode The 271 bus line Fraserburgh has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Fraserburgh: 7:35 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 271 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 271 bus arriving. Direction: Fraserburgh 271 bus Time Schedule 37 stops Fraserburgh Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:35 AM Low Street, Banff Tuesday 7:35 AM Water Lane, Banff Water Lane, Banff Wednesday 7:35 AM Bridge Road, Banff Thursday 7:35 AM Bridge Road, Scotland Friday 7:35 AM Union Road, Macduff Saturday Not Operational Hutcheon Street, Macduff Shore Street, Macduff Nicols Brae, Macduff 271 bus Info Direction: Fraserburgh Market Street, Macduff Stops: 37 Trip Duration: 55 min Mill Street, Macduff Line Summary: Low Street, Banff, Water Lane, Banff, Bridge Road, Banff, Union Road, Macduff, Moray Street, Macduff Hutcheon Street, Macduff, Nicols Brae, Macduff, Market Street, Macduff, Mill Street, Macduff, Moray Ewen Crescent, Macduff Street, Macduff, Ewen Crescent, Macduff, Cotton Hill Quarry, Macduff, Fairburn Cottages, Longmanhill, Shop, Sauchenbush, Bridge Of Bo, Netherbrae, Road Cotton Hill Quarry, Macduff End, Netherbrae, Hillside Of Cook, Crudie, Woodside, New Byth, Langleys, New Pitsligo, Craigmaud, New Fairburn Cottages, Longmanhill Pitsligo, Woodhead, Tyrie, Bell Terrace, Tyrie, Church Rd End, Tyrie, Strichen Junction, Tyrie, Crossroads, Shop, Sauchenbush Fraserburgh, Percyhorner Cottage, Fraserburgh, Asda, Fraserburgh, -

Fraser She Was Born in 1910 and Died 2003

Notes: 1. Woman keep their maiden name in the telling of this tale to avoid confusion. In fact, in Scotland many woman used their maiden name throughout their married life . 2. Spelling was pretty fluid before the 20th century so expect to see names and places spelled differently over time. Accent also changed spelling and people wrote down what they heard for example Mairshell for Marshall. 3. The map to the right shows Aberdeen and Banffshire the birthplaces of most of the people in this story. In the main, they inhabited the far north of the counties. 4. I've tried to use our great-great-great-great-great-grand parents as a starting point. They are abbreviated to 5x Great Grandparents in the texts 1 This is the start of Jennifer and Keith Jolly's family history and the reason I'm starting with our maternal grandmother's family is simple. It has been the easiest to follow back in time. The Nobles of Broadsea have been well researched and the records in Banffshire are far more complete than those I've found in other parts of Scotland. In the main, these people hug the coast line following the work whether that be in fishing, making barrels or curing fish. We have butchers, blacksmiths, masons, and tailors and a multitude of people working the land often as farm servants but sometimes as crofters. In the beginning we're all in the far north of Scotland up around that piece of water we call the Moray firth. Over time people will move south to gain employment but for this branch of the family that still means north of the river Tay. -

Pre-Application Consultation (PAC) Report

Moray West Offshore Wind Farm and Offshore Transmission Infrastructure (OfTI) Pre-application Consultation (PAC) Report This Pre-application Consultation (PAC) Report has been prepared in accordance with requirements of the Marine Licencing (Pre-application Consultation) (Scotland) Regulations 2013 in support of an application for a Marine Licence for the Moray West Offshore Transmission Infrastructure (OfTI) components of the Moray West Offshore Wind Farm. 1. Proposed Licensable Marine Activity Please describe below or, where there is insufficient space, in a document attached to this form the proposed licensable marine activity, including its location Moray Offshore Windfarm (West) Limited (known as Moray West) are proposing to develop the following licensable marine activities/project; Moray West Offshore Wind Farm and Offshore Transmission Infrastructure (OfTI). Maps showing the location of the Offshore Wind Farm and OfTI are presented in Appendix A. The Moray West Offshore Wind Farm will comprise up to 85 Wind Turbine Generators (WTGs), associated substructures and seabed foundations, inter-array cables and any scour protection around substructures or cable protection. The OfTI comprises up to two Offshore Substation Platforms (OSPs) which will be located within the Moray West Site, OSP interconnector cables and two offshore export cable circuits which will be located within the Offshore Export Cable Corridor and will be used to transmit the electricity generated by the offshore wind farm to shore. The offshore export cable circuits come ashore in the Landfall Area which is located on the Aberdeenshire Coast between Findlater Castle and Redhythe Point, approximately 65 km south of the Moray West Site. The Marine Licensing (Pre-application Consultation) (Scotland) Regulations 2013 apply to all licensable marine activities (as defined under the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010) within Scottish marine area, the area of sea within the seaward limits of the territorial sea (0 – 12 nautical miles [nm]). -

Banff Castle

UE 12 2010 - ISS insideinside thisthis issueissue .. .. .. newsnews fromfrom aroundaround thethe areaarea .. .. .. TransportTransport newsnews .. .. .. andand lotslots moremore partnershipupdate Chairman’s Letter Design: Kay Beaton, elcome to the latest edition of the Banffshire Partnership PURPLEcreativedesign WNewsletter. During the year one of the longest serving directors Eddie Bruce Printed by had to stand down due to ill-health. Eddie was a very valued Halcon, Aberdeen member of the board and I would like to record our thanks for community transport Paper his contribution and wise counsel over the years. Printed on environ- Also during the year Evelyn Elphinstone, our administrator and book-keeper retired. Evelyn had worked for the Partnership for many mentally friendly paper. years and I would also like to record our thanks for her hard work and Woodpulp sourced from dedication over the years. sustainable forests. This has been a busy and challenging year for BPL. Once again we entered into a formal Service Level Agreement with Aberdeenshire Council which commenced on 1st April and Board Of Directors runs to 31st March 2010. This is core funding for the Partnership which allows it to carry Directors can be out its very important tasks helping many community groups throughout our operational “keeping the community moving” area. contacted through the With the expected squeeze on local government finances in the coming years there Partnership is no guarantee that such funding will endure at the required level. However, both community use minibus office - 01261 843286. Aberdeenshire Council and the Local Rural Partnerships across the shire are keen to ensure that they survive any reduced funding from the Scottish Government. -

Ellon P&R L Oldmeldrum L Inverurie 49 MONDAY to FRIDAY SATURDAY Service No

bustimes from 08 January 2018 page 1 of 28 Stagecoach North Scotland Buchan Travel Guide from 08 January 2018 This booklet contains all the timetable and route information you’ll need for travelling around the Buchan area, including maps of our routes on the centre pages. Easy Access We make every effort to provide wheelchair accessible vehicles on our services, however, there may be exceptional circumstances when we need to substitute another bus rather than miss a journey. Real-Time Tracking We provide real-time bus information on all our routes, enabling our passengers to check exactly when their bus will arrive. You can plan your journey on www.stagecoachbus.com or using our app. Timetable Variations A normal service will operate on Good Friday and Easter Monday. A Saturday service will be in operation on May Day. No services will operate on Christmas Day and New Years Day. Adjusted services will operate during the festive period, please see separate publications issued for this period. School Holidays Aberdeenshire school holidays for 2018 are: 12 February 2018, 30 March - 13 April 2018, 7 May 2018, 9 July - 20 August 2018, 15 - 26 October 2018. College Holidays North East Scotland College holidays for 2018 are: 26 - 29 January 2018, 2 - 13 April 2018, 7 May 2018, 3 July - 15 August 2018. Ellon P&R l Oldmeldrum l Inverurie 49 MONDAY TO FRIDAY SATURDAY Service No. 49 49 49 49 49 49 Service No. 49 49 49 49 49 Ellon Park & Ride 0747 0930 1253 1433 1630 1720 Ellon Park & Ride 0750 0927 1243 1448 1632 Market Street Interchange 0750 0933