Based on Case Studies of 15 Allnews Radio Stations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who Pays Soundexchange: Q1 - Q3 2017

Payments received through 09/30/2017 Who Pays SoundExchange: Q1 - Q3 2017 Entity Name License Type ACTIVAIRE.COM BES AMBIANCERADIO.COM BES AURA MULTIMEDIA CORPORATION BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX MUSIC BES ELEVATEDMUSICSERVICES.COM BES GRAYV.COM BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IT'S NEVER 2 LATE BES JUKEBOXY BES MANAGEDMEDIA.COM BES MEDIATRENDS.BIZ BES MIXHITS.COM BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES MUSIC CHOICE BES MUSIC MAESTRO BES MUZAK.COM BES PRIVATE LABEL RADIO BES RFC MEDIA - BES BES RISE RADIO BES ROCKBOT, INC. BES SIRIUS XM RADIO, INC BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES STARTLE INTERNATIONAL INC. BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STORESTREAMS.COM BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES TARGET MEDIA CENTRAL INC BES Thales InFlyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM BES SIRIUS XM RADIO, INC CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT MUSIC CHOICE PES MUZAK.COM PES SIRIUS XM RADIO, INC SDARS 181.FM Webcasting 3ABNRADIO (Christian Music) Webcasting 3ABNRADIO (Religious) Webcasting 8TRACKS.COM Webcasting 903 NETWORK RADIO Webcasting A-1 COMMUNICATIONS Webcasting ABERCROMBIE.COM Webcasting ABUNDANT RADIO Webcasting ACAVILLE.COM Webcasting *SoundExchange accepts and distributes payments without confirming eligibility or compliance under Sections 112 or 114 of the Copyright Act, and it does not waive the rights of artists or copyright owners that receive such payments. Payments received through 09/30/2017 ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting ACRN.COM Webcasting AD ASTRA RADIO Webcasting ADAMS RADIO GROUP Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting ADORATION Webcasting AGM BAKERSFIELD Webcasting AGM CALIFORNIA - SAN LUIS OBISPO Webcasting AGM NEVADA, LLC Webcasting AGM SANTA MARIA, L.P. -

Microsoft Outlook

Emails pertaining to Gateway Pacific Project For April 2013 From: Jane (ORA) Dewell <[email protected]> Sent: Monday, April 01, 2013 8:12 AM To: '[email protected]'; Skip Kalb ([email protected]); John Robinson([email protected]); Brian W (DFW) Williams; Cyrilla (DNR) Cook; Dennis (DNR) Clark; Alice (ECY) Kelly; Loree' (ECY) Randall; Krista Rave-Perkins (Rave- [email protected]); Jeremy Freimund; Joel Moribe; 'George Swanaset Jr'; Oliver Grah; Dan Mahar; [email protected]; Scott Boettcher; Al Jeroue ([email protected]); AriSteinberg; Tyler Schroeder Cc: Kelly (AGR) McLain; Cliff Strong; Tiffany Quarles([email protected]); David Seep ([email protected]); Michael G (Env Dept) Stanfill; Bob Watters ([email protected]); [email protected]; Jeff Hegedus; Sam (Jeanne) Ryan; Wayne Fitch; Sally (COM) Harris; Gretchen (DAHP) Kaehler; Rob (DAHP) Whitlam; Allen E (DFW) Pleus; Bob (DFW) Everitt; Jeffrey W (DFW) Kamps; Mark (DFW) OToole; CINDE(DNR) DONOGHUE; Ginger (DNR) Shoemaker; KRISTIN (DNR) SWENDDAL; TERRY (DNR) CARTEN; Peggy (DOH) Johnson; Bob (ECY) Fritzen; Brenden (ECY) McFarland; Christina (ECY) Maginnis; Chad (ECY) Yunge; Douglas R. (ECY) Allen; Gail (ECY) Sandlin; Josh (ECY) Baldi; Kasey (ECY) Cykler; Kurt (ECY) Baumgarten; Norm (ECY) Davis; Steve (ECY) Hood; Susan (ECY) Meyer; Karen (GOV) Pemerl; Scott (GOV) Hitchcock; Cindy Zehnder([email protected]); Hallee Sanders; [email protected]; Sue S. PaDelford; Mary Bhuthimethee; Mark Buford ([email protected]); Greg Hueckel([email protected]); Mark Knudsen ([email protected]); Skip Sahlin; Francis X. Eugenio([email protected]); Joseph W NWS Brock; Matthew J NWS Bennett; Kathy (UTC) Hunter; ([email protected]); Ahmer Nizam; Chris Regan Subject: GPT MAP Team website This website will be unavailable today as maintenance is completed. -

Curriculum Vitae Brenda J. Baker

CURRICULUM VITAE BRENDA J. BAKER Associate Professor of Anthropology Center for Bioarchaeological Research School of Human Evolution & Social Change Arizona State University Tempe, AZ 85287-2402 Phone: (480) 965-2087; Fax: (480) 965-7671; E-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION 1992 Ph.D. in Anthropology, University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Dissertation: Collagen Composition in Human Skeletal Remains from the NAX Cemetery (A.D. 350-550) in Lower Nubia. Doctoral committee chair: Dr. George J. Armelagos 1983 M.A. in Anthropology, University of Massachusetts, Amherst. 1981 B.A. in Anthropology, with Honors, Northwestern University Honors thesis: A Bioarchaeological Analysis of N155-2: A Prehistoric Mortuary Structure from Nauvoo, lllinois. Advisor: Dr. Jane E. Buikstra PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS 2002-present Associate Professor, School of Human Evolution & Social Change (Department of Anthropology prior to 2005), Arizona State University. 1998-2002 Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, Arizona State University. 1994-1998 Senior Scientist (Bioarchaeology), Curator of Human Osteology and Director of Repatriation Program, Anthropological Survey, New York State Museum, Albany, NY. Developed research program concerning human skeletal remains in the museum's collections and in New York State; consulted on identification of human remains for other agencies (e.g., State Police); supervised staff and student interns in inventory work for the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA); oversaw budget and grants for NAGPRA and research projects; served on museum exhibit planning and collections committee; participated in public programming. 1995-1998 Adjunct Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, University at Albany, SUNY. 1993-1994 Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Moorhead State University, MN. -

In the United States Bankruptcy Court for the District of Delaware

IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE In re: ) Chapter 11 ) PACIFIC ENERGY RESOURCES LTD., et al.,' ) Case No. 09-10785 (KJC) ) (Jointly Administered) Liquidating Debtors. ) AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE STATE OF CALIFORNIA ) ) ss: COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES ) Ann Mason, being duly sworn according to law, deposes and says that she is employed by the law firm of Pachulski Stang Ziehl & Jones LLP, attorneys for the Debtors in the above- captioned action, and that on the 5 th day of October 2012 she caused a copy of the following documents to be served upon the parties on the attached service lists in the manner indicated: Liquidating Debtors’ Notice of Motion for Order Approving Assignment of Assets to Hilcorp Alaska, LLC and Distribution of the Proceeds Thereof ("Notice") Liquidating Debtors’ Motion for Order Approving Assignment of Assets to Hilcorp Alaska, LLC and Distribution of the Proceeds Thereof ("Motion") Because the service list was so large (nearly 9,000 parties), the copies of the Motion that were served on parties in interest other than the core service list did not contain copies of Exhibits A, B or D. However, the service copies of the Motion and the Notice advised parties in interest that they can obtain copies of Exhibits A, B and D by making a request, in writing, to counsel for the Liquidating Debtors at the address listed in the signature block to the Motion. The Liquidating Debtors (and the last four digits of each of their federal tax identification numbers) are: Pacific Energy Resources Ltd. (3442); Pacific Energy Alaska Holdings, LLC (tax I.D. -

Theory and Practice of Counseling and Psychotherapy

ninth edition Theory and Practice of Counseling and Psychotherapy GERALD COREY California State University, Fullerton Diplomate in Counseling Psychology American Board of Professional Psychology $XVWUDOLDä%UD]LOä-DSDQä.RUHDä0H[LFRä6LQJDSRUHä6SDLQä8QLWHG.LQJGRPä8QLWHG6WDWHV Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. About the Author GERALD COREY is a Professor Emeritus of Human Serv- ices at California State University at Fullerton and a licensed psychologist. He received his doctorate in counseling from the University of Southern California. He is a Diplomate in Counseling Psychology, American Board of Professional Psychology; a National Certified Counselor; a Fellow of the American Psychological Association (Counseling Psychol- ogy); a Fellow of the American Counseling Association; and Associated Press a Fellow of the Association for Specialists in Group Work. He also holds memberships in the American Group Psycho- therapy Association; the American Mental Health Counselors Association; the As- sociation for Spiritual, Ethical, and Religious Values in Counseling; the Associa- tion for Counselor Education and Supervision; and the Western Association for Coun selor Education and Supervision. Along with Marianne Schneider Corey, Jerry received the Lifetime Achieve- ment Award from the American Mental Health Counselors Association in 2011 and the Eminent Career Award from the Association for Specialists in Group Work in 2001. -

Pierce College Student Handbook

PIERCE COLLEGE FORT STEILACOOM AND PUYALLUP 2018-19 Academic Calendar For Pierce College at JBLM calendar dates, see www.pierce.ctc.edu/calendar SUMMER QUARTER WINTER QUARTER July 2 Instruction begins Jan. 7 Instruction begins July 2-5 Add classes without Jan. 7-9 Add classes without instructor signature instructor signature July 3 100% refund ends Jan. 10-18 Add classes with instructor (first 4-week session) signature July 5 100% refund ends (8-week classes) Jan. 11 100% refund ends July 9 50% refund ends Jan. 18 Last day to withdraw so class (first 4-week session) will not show on transcript^ July 9-16 Add classes with instructor Jan. 21 Martin Luther King, Jr. Day** signature (8-week classes) Jan. 25 50% refund ends July 16 Last day to withdraw so class Jan. 29 Pre-registration advising will not show on transcript (8-week classes)^ Feb. 7 Faculty Assessment Day* July 16 50% refund ends (8-week classes)^ Feb. 8 All District In-service Day** July 26 Instruction ends Feb. 12 Spring student registration begins (first 4-week session) Feb. 18 Presidents' Day** July 30 Instruction begins Feb. 25 Last day to withdraw/continuous (second 4-week session) entry registration ends July 31 100% refund ends Feb. 26 Open student registration begins (second 4-week session) March 21 Instruction ends Aug. 6 50% refund ends (second 4-week session) March 22, 25, 26 Final exams Aug. 6 Last day to withdraw/continuous April 1 Graduation applications due for name in entry registration ends graduation program Aug. 22 Instruction ends SPRING QUARTER April 8 Instruction begins FALL QUARTER April 8-10 Add classes without Sept. -

Puget Sound Area 950 Use

Puget Sound Area 950 Use FREQ. STATION FACILITY IDHOR/VERTANALOG DIG. TX. LOC. RX. LOC. CALL SIGN EMISSION TX AZ BANDWIDTH Lat. Long DATE 944.0000 944.2500 KMTT 18513 HORZ Digital MET PARK SEATTLE TIGER MT WLP634 300KF8E 115.0 944.2500 KHTP HORZ Digital Met. Park West WTM/Cougar WLP634 500KD7W 500khz 47-36-58.3 122-19-49.4 Oct. 21, 2013 944.5000 KPLZ 21663 VERT Digital FISHER PLAZA CAPITOL HILL SEATTE WLF845 300KD7W 342.9 11-Nov-2013 944.5000 KRWM 53870 HORZ Digital EAST BREMERTON ????????? WLG525 500KF9W 87 11-Nov-2013 944.5000 KXXO 67027 VERT CRAWFORD MT ROOSTER ROCK WLP283 500KF9W 135.6 11-Nov-2013 944.7500 KFMY 51167 HORZ 1803 STATE ST OLYMPIA CAPITOL PEAK WPYK602 500KF9W 248.4 11-Nov-2013 944.7500 KDDS 33622 HORZ 1803 STATE ST OLYMPIA CAPITOL PEAK WPY1744 500KF9W 248.4 11-Nov-2013 944.7500 KRWM 53870 HORZ Digital CAPITOL HILL SEATTLE COUGAR MT WPJD816 500KF9E 117.8 11-Nov-2013 944.8750 KCED 63026 VERT ACROSS CAMPUS ACROSS CAMPUS WLI862 250KF9W 288 11-Nov-2013 944.8750 KSUH 32339 HORZ OLD STUDIO FIFE PUTLLUP TX WIJ771 250KF9W 144 11-Nov-2013 945.0000 KMPS 20356 VERT Digital CAPITOL HILL SEATTLE TIGER MT ATC SITE WBG555 250KD7E 116 11-Nov-2013 945.1250 KCED 63026 VERT ACROSS CAMPUS ACROSS CAMPUS WLI862 250KF9W 288 11-Nov-2013 945.1250 KSUH 32339 HORZ OLD STUDIO FIFE PUTLLUP TX WIJ771 250KF9W 144 11-Nov-2013 945.2500 KDDS 33622 HORZ TUMWATER HILL NORTH MT WQBY639 300KD7W 316.2 11-Nov-2013 945.2500 KNBQ 33829 HORZ KFNK TX EATONVILLE CAPITOL PEAK PENDING 180KF3C 283 11-Nov-2013 945.5000 KBSG 33682 HORZ Analog MET PARK SEATTLE TIGER MT -

Section 9202 Joint Information Center Manual

Section 9202 Joint Information Center Manual Communicating during Environmental Emergencies Northwest Area: Washington, Oregon, and Idaho able of Contents T Section Page 9202 Joint Information Center Manual ........................................ 9202-1 9202.1 Introduction........................................................................................ 9202-1 9202.2 Incident Management System.......................................................... 9202-1 9202.2.1 Functional Units .................................................................. 9202-1 9202.2.2 Command ............................................................................ 9202-1 9202.2.3 Operations ........................................................................... 9202-1 9202.2.4 Planning .............................................................................. 9202-1 9202.2.5 Finance/Administration....................................................... 9202-2 9202.2.6 Mandates ............................................................................. 9202-2 9202.2.7 Unified Command............................................................... 9202-2 9202.2.8 Joint Information System .................................................... 9202-3 9202.2.9 Public Records .................................................................... 9202-3 9202.3 Initial Information Officer – Pre-JIC................................................. 9202-3 9202.4 Activities of Initial Information Officer............................................ 9202-4 -

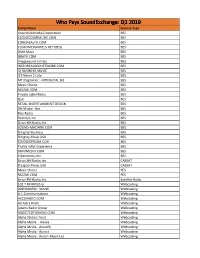

Licensee Count Q1 2019.Xlsx

Who Pays SoundExchange: Q1 2019 Entity Name License Type Aura Multimedia Corporation BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX Music BES GRAYV.COM BES Imagesound Limited BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IO BUSINESS MUSIC BES It'S Never 2 Late BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES Music Choice BES MUZAK.COM BES Private Label Radio BES Qsic BES RETAIL ENTERTAINMENT DESIGN BES Rfc Media - Bes BES Rise Radio BES Rockbot, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES Thales Inflyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM BES Vibenomics, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT Music Choice PES MUZAK.COM PES Sirius XM Radio, Inc Satellite Radio 102.7 FM KPGZ-lp Webcasting 999HANKFM - WANK Webcasting A-1 Communications Webcasting ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting Ad Astra Radio Webcasting Adams Radio Group Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting Aloha Station Trust Webcasting Alpha Media - Alaska Webcasting Alpha Media - Amarillo Webcasting Alpha Media - Aurora Webcasting Alpha Media - Austin-Albert Lea Webcasting Alpha Media - Bakersfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Biloxi - Gulfport, MS Webcasting Alpha Media - Brookings Webcasting Alpha Media - Cameron - Bethany Webcasting Alpha Media - Canton Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbia, SC Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbus Webcasting Alpha Media - Dayton, Oh Webcasting Alpha Media - East Texas Webcasting Alpha Media - Fairfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Far East Bay Webcasting Alpha Media -

Common Frequency Simulation #2

Via Electronic Mail November 12, 2010 Marlene H. Dortch Federal Communications Commission Office of the Secretary Room TW-A35 445 12 th Street, SW Washington, DC 20554 Re: LPFM Proceeding, MM Docket No. 99-25 Dear Ms. Dortch: Common Frequency (“CF”) previously submitted a letter and study on September 28, 2010 to the FCC concerning the shortcomings of implementing a ten application processing cap for pending translators in Auction No. 83. Since then a smattering of comments on translator processing and questions regarding the comment have beckoned CF to provide further clarification in this follow-up. In this comment, CF responds to questions about our earlier study, addresses the proposals from other parties, and provides a second study with a more exhaustive methodology to provide better insight on our position. The translator preclusion study submitted by CF was produced to communicate that the ten application cap did not appear effective at providing more opportunity for LPFM in urban areas. At the heart of the matter, in our simulation, if ~97% of the top 150 urban MXs are taken by translators then there would be no difference in these urban markets if there was a ten application cap or was no ten application cap . Although we additionally expressed that very few channels would be left for LPFM in major urban areas—a generalization that could require the processing of further data on CF’s part to be exact —this observation is separate from reporting that 97% of the top urban MXs being consumed, which was foremost reported in CF’s executive summary. -

July 2006 Vol.67, No

-. • . I ~* ~/~~ : 0ur Success! * 't*" 1~ its insureds. Isn't it time you JOINED THE MOVEMENT and insured with AIM? AIM: For the Difference! Attorneys Insurance Mutual of Alabama, Inc. 200 Inverness Parkway Telephone (205) 980-0009 Toll Free (800) 526-1246 Birmingham , Alabama 35242-4813 FAX (205) 980-9009 Service • Strength • Sec u rity [ml -UT.lffl ISI ALABAMA --ll dh•iJion o/-- [NS URAN CE SPECIALISTS, INC. ISi ALABAMA, a division of Insurance Specialists, Inc . ( ISi), in its fift h decade of service to the national association marketplace, is proud to have maintained service to the Alabama State Bar since 1972. ISi is recogni7.£<1as a leader among affinity third party administrators, and maintains strong affiliations with leading carriers of its specialty products. Association and affi.nity gro ups provide added value to Membership benefits through offerings of these qua.lity insurance plans tailored to meet the needs of Members. INSURANCE PROGRAMS AVAILABLE TO ALABAMA STATE BAR MEMBERS Select tlie products tlrat you want i11formatio11011 from tlie list below, complete tlie form and retum via fax or mail. Tlrere is 110 obligation. 0 Long Term Disability 0 AccidentaJ Death & Dismemberment Plan D Individual Tenn Life 0 Business Overhead Expense 0 Hospital Income Plan D Medica re Supp lement Plan Alahlnu S1:1teBnt Mt:fflbn N11mc AJI< Spou~NarM ,.,.. ' ordq)c-ndcntJ OffictAddtffl (Sum, Ory.Sr,1tt,Zip) OfficePhone HomePhone Fu Q«upat1on E-mailAddm.a: 0,/1 me for 011 appointmelllto discwscoverage at: O Home D Office RETURN COMPLETED REPLY CARD TO: Fax: 843-525-9992 Mail:[$[ ADMINISTRATIVBCENTBII • SALES · P.O. -

530 CIAO BRAMPTON on ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb

frequency callsign city format identification slogan latitude longitude last change in listing kHz d m s d m s (yy-mmm) 530 CIAO BRAMPTON ON ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb 540 CBKO COAL HARBOUR BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N50 36 4 W127 34 23 09-May 540 CBXQ # UCLUELET BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 56 44 W125 33 7 16-Oct 540 CBYW WELLS BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N53 6 25 W121 32 46 09-May 540 CBT GRAND FALLS NL VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 57 3 W055 37 34 00-Jul 540 CBMM # SENNETERRE QC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 22 42 W077 13 28 18-Feb 540 CBK REGINA SK VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N51 40 48 W105 26 49 00-Jul 540 WASG DAPHNE AL BLK GSPL/RELIGION N30 44 44 W088 5 40 17-Sep 540 KRXA CARMEL VALLEY CA SPANISH RELIGION EL SEMBRADOR RADIO N36 39 36 W121 32 29 14-Aug 540 KVIP REDDING CA RELIGION SRN VERY INSPIRING N40 37 25 W122 16 49 09-Dec 540 WFLF PINE HILLS FL TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 93.1 N28 22 52 W081 47 31 18-Oct 540 WDAK COLUMBUS GA NEWS/TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 540 N32 25 58 W084 57 2 13-Dec 540 KWMT FORT DODGE IA C&W FOX TRUE COUNTRY N42 29 45 W094 12 27 13-Dec 540 KMLB MONROE LA NEWS/TALK/SPORTS ABC NEWSTALK 105.7&540 N32 32 36 W092 10 45 19-Jan 540 WGOP POCOMOKE CITY MD EZL/OLDIES N38 3 11 W075 34 11 18-Oct 540 WXYG SAUK RAPIDS MN CLASSIC ROCK THE GOAT N45 36 18 W094 8 21 17-May 540 KNMX LAS VEGAS NM SPANISH VARIETY NBC K NEW MEXICO N35 34 25 W105 10 17 13-Nov 540 WBWD ISLIP NY SOUTH ASIAN BOLLY 540 N40 45 4 W073 12 52 18-Dec 540 WRGC SYLVA NC VARIETY NBC THE RIVER N35 23 35 W083 11 38 18-Jun 540 WETC # WENDELL-ZEBULON NC RELIGION EWTN DEVINE MERCY R.