Toward a Theory of Consumer Interaction with Mobile Technology Devices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newton Solutions 1

page1 9/22/95 9:55 AM Page 1 Solutions Guide Software, Peripherals and Accessories for Newton PDAs Information Management Desktop Integration Communications Vertical Market Solutions Newton Accessories Newton Software Development page2 9/22/95 9:59 AM Page 1 Suddenly Newton understands everything you write. All you need is Graffiti.® The And here is what some of fastest, most accurate way to the over 20,000 real users are enter text on saying about Graffiti: a Newton.™ Guaranteed. “Graffiti makes a useful device How fast? twice as useful. I now use my Try over 30 Newton constantly.” words a minute. How accurate? “I can take notes at a meeting About 100%. as fast as I print… Every bit as fast And Graffiti takes only twen- as paper and pen.” ty minutes to learn. That’s “I have been using my Newton because it’s really just a simpli- much more than before because fied version of the same Graffiti makes it much easier to alphabet you learned in the first enter data on the fly.” grade. “Just received Graffiti. It’s all they claim and more. I think it’s a must for Newton.”* See for yourself how much you need Graffiti. Call 1-800-881-7256 to order Graffiti for only $79—with a 60-day money-back guarantee. From outside the USA, please call 408-848-5604. *Unsolicited user comments from Graffiti registration cards and Internet news groups. ©1994 Graffiti is a registered trademark and ShortCuts is a trademark of Palm Computing. All other trademarks are property of their respective holders. -

Newton Messagepad 100

Newton MessagePad 100 The Newton MessagePad 100 per- of your time, find your way around sonal digital assistant is the affordable unfamiliar cities, and even deliver member of the Newton family. better-organized speeches. And while it looks like the original The Newton MessagePad 100 has Newton MessagePad, it has important powerful handwriting-recognition new features that make it more capabilities—for both printed and Features powerful and more useful. cursive writing. So it can transform Built-in applications These features mean that the your handwriting into text letter • Let you capture, manage, and Newton MessagePad 100 can help by letter or word by word. It can communicate business and personal information you manage information; stay in also leave your notes handwritten • Allow free-form notetaking—mixing touch via fax, e-mail, and paging; and should you wish to defer recognition handwriting, printed text, and graphics until later. • Turn printed or cursive handwriting into exchange information with your typed text or leave it handwritten computer. And as time goes by, it learns about • Recognize writing letter by letter or word by word It can help you stay in touch— you, your handwriting, and the way • Update daily to-do lists and help assign and communicate—more effectively. you work, helping you get more done. priorities to tasks It comes with a built-in notepad, • Let you create name files for colleagues You can send faxes and receive pages and friends using a familiar business-card and messages. Tap into on-line to-do list, datebook, and name file to format get you started. -

Accessionindex: TCD-SCSS-T.20170830.010 Accession Date: 30-Aug-2017 Accession By: Hans-Jurgen Kugler Object Name: Apple Newton M

AccessionIndex: TCD-SCSS-T.20170830.010 Accession Date: 30-Aug-2017 Accession By: Hans-Jurgen Kugler Object name: Apple Newton MessagePad 2000 Vintage: c.1997 Synopsis: Apple personal digital assistant (PDA) with handwriting recognition, plus keyboard and power supply, Model: H0149, S/N: ????. Description: The Apple Newton was introduced in Aug-1993 after a 6-year gestation that also involved gestation of the company Advanced RISC Machines (ARM). It began with ambitious goals but eventually was re-imagined as a personal digital assistant (PDA). Similar devices had existed for a decade, for example the Psion Organiser was introduced in 1984, but they were not called PDAs. Not only did the Newton introduce the term PDA, but it also became the first such device to feature handwriting recognition. The Newton was championed by John Sculley, and then discontinued by his rival Steve Jobs in 1998 after the latter rejoined Apple. It is very likely that the concept led directly to the iPad and iPhone. An operating system, NewtonOS , and a language, NewtonScript , were invented for it, with garbage collection, soup storage and user-interface toolkit, specifically tuned for designs with large ROM and small RAM capacities. The original Newton MessagePad (Model H1000 or Junior ) had a 20MHz ARM 610 CPU, 4MB of ROM, 640kB of RAM, a 336 x 240 monochrome display, RS422 serial and LocalTalk interfaces, and SHARP ASK infrared communications. It also had one PCMCIA-II slot (5V or 12V). It ran NewtonOS versions 1.0-1.11, and it could be powered either from four internal AAA or NiCd rechargeable batteries or an external power supply. -

Why Did Apple Kill Newton?

From Pen Computing Magazine #22, June 1998 Why Did Apple Kill Newton? ©Copyright 1998 David MacNeill Early Friday morning, February 27, 1998, Apple Computer made official what the Newton cognoscenti had strongly suspected for six months: the Newton handheld computing platform was dead. The rather terse press release gave the basic facts: Apple will cease all Newton OS hardware and software development, no more products will be made after the existing stock is depleted, and Apple will continue to provide support to users. Brief mention was made of development of a new low-cost Mac OS-based mobile device in the future, but no details were offered. But the most galling omission was the lack of an answer to the question on the minds of hundreds of thousands of shocked, angry Newton owners: Why? Before I attempt to answer this question, let’s take a quick tour of the mercurial five-year career of Newton. This will serve to prepare you for the several explanations we will be considering. A brief history of Newton During its turbulent five-year life, Newton technology was close to death several times, yet always managed to survive. Department heads came and went, but the essential concept of the personal digital assistant (PDA) was too compelling to die easily: A small, inexpensive, pen-based computing device that would accompany you everywhere, and that would learn enough about you to make informed assumptions about how to help you keep track of the myriad little bits of information we all must carry. It would be simple enough for anyone to use, a true computer for the rest of us. -

List of Palm OS Versions Included on Palm Handhelds, and Possible Upgrades

List of Palm OS versions included on Palm handhelds, and possible upgrades www.palm.com < Home < Support < Knowledge Library Article ID: 10714 List of Palm OS versions included on Palm handhelds, and possible upgrades Palm OS® is the operating system that drives Palm devices. In some cases, it may be possible to update your device with ROM upgrades or patches. Find your device below to see what's available for you: Centro Treo LifeDrive Tungsten, T|X Zire, Z22 Palm (older) Handspring Visor Questions & Answers about Palm OS upgrades Palm Centro™ smartphone Device Palm OS Handheld Palm OS version Palm Desktop & version (out- Upgrade/Update after HotSync Manager of-box) available? upgrade/update update Centro (AT&T) 5.4.9 No N/A No Centro (Sprint) 5.4.9 No N/A No Treo™ 755p smartphone Device Palm OS Handheld Palm OS version Palm Desktop & version (out- Upgrade/Update after HotSync Manager of-box) available? upgrade/update update Treo 755p (Sprint) 5.4.9 No N/A No Treo™ 700p smartphones Device Palm OS Handheld Palm OS version Palm Desktop & version (out- Upgrade/Update after HotSync Manager of-box) available? upgrade/update update Treo 700p (Sprint) Garnet Yes N/A No 5.4.9 Treo 700p (Verizon) Garnet No N/A No 5.4.9 Treo™ 680 smartphones Device Palm OS Handheld Palm OS version Palm Desktop & version (out- Upgrade/Update after HotSync Manager of-box) available? upgrade/update update Treo 680 (AT&T) Garnet Yes 5.4.9 No 5.4.9 Treo 680 (Rogers) Garnet No N/A No 5.4.9 Treo 680 (Unlocked) Garnet No N/A No 5.4.9 Treo™ 650 smartphones Device Palm OS -

Tealtracker User's Manual Table of Contents

TealTracker User's Manual Program Version 1.44 Last Updated: October 4, 2010 Table of Contents Introduction..................................................................................................................... 1 Description.........................................................................................................................1 Contents ............................................................................................................................1 PalmOS Files (.ZIP Archive)............................................................................................1 Windows Mobile Files (.EXE Installer) ..............................................................................1 Windows Desktop PC File (.EXE Program) ......................................................................1 Installing the Program .........................................................................................................2 Chapter 1 – Overview.................................................................................................... 3 Main Screen.......................................................................................................................3 Time-Clock View ............................................................................................................3 Manual Entry View..........................................................................................................3 Chapter 2 – Accounts .................................................................................................. -

Palm OS Is One of the Most Popular Handheld Operating Systems on the Planet

Palm and Treo Hacks By Scott MacHaffie ............................................... Publisher: O'Reilly Pub Date: October 2005 ISBN: 0-596-10054-X Pages: 234 Table of Contents | Index Palm OS is one of the most popular handheld operating systems on the planet. From the newest Tungstens and Treos all the way down the family tree, Palms are everywhere. Although the Palm OS is simple to learn and use, there is more to it than meets the eye--from new features in the Palm to capabilities you can get with add-on software, the Palm can be made to do quite a lot. Palm and Treo Hacks gives you tips and tools that show you how to make the most of your Palm. A few minutes spent reading some of the hacks in this book will save you hours of research. Inside this book, you'll learn how to: Find great applications for your Palm and make the most of the ones you're using now Get super-organized, getting more from the built-in Personal Information Manager and learning how to manage complex projects with your Palm Extend the Palm with must-have software and hardware add-ons Take your Palm online, reading email, surfing the web, and sending instant messages Get some rest and relaxation with your Palm, whether it's listening to music, playing classic games, or watching video Written for beginning to experienced Palm users, Palm and Treo Hacks is full of practical, ingenious tips and tricks you can apply immediately. Whether you're looking to master the built-in applications or you want to trick out your Palm to its fullest extent, this book will show you how to get it. -

Messagepad Accessories

MessagePad Accessories Now you can make your Apple range of accessory products—from network. You can also work for MessagePad even more valuable, connectivity solutions to battery hours without having to change and make it work even more enhancements to storage options. batteries. And you can protect efficiently. With these optional accessories, your MessagePad—and its acces- Because no matter which you can print letters, connect to sories—in a leather carrying case, MessagePad product you have, your personal computer, or gain wherever you go. you can choose from a broad access to information on your Accessories Newton Keyboard Rechargeable Battery Pack MessagePad and Newton Keyboard Nylon Now you can enter information into your MessagePad with This rechargeable nickel-cadmium battery pack can be Carrying Case Newton 2.0 or 2.1 as fast as you can type. The comfortable one of the most effective ways to keep your MessagePad This book-style, nylon carrying case is a lightweight, touchtype keyboard is lightweight and portable and comes 120 or 130 running. all-in-one solution for your MessagePad 2000 or 2100, with an attractive carrying case, so you can take it where- and Newton Keyboard. A built-in adjustable easel allows MessagePad Battery Charging Station ever you take your MessagePad. It comes in several for easy viewing of the MessagePad in any lighting Sit your MessagePad 120 or 130 onto this charging station international versions. environment. to run it on AC power while recharging its batteries. You Newton 9W Power Adapter can simultaneously quick-charge its external battery pack MessagePad Telescoping Pen The Newton 9W Power Adapter lets you run your in two to three hours. -

A Study of the Growth and Evolution of Personal Computer Devices Throughout the Pc Age

A STUDY OF THE GROWTH AND EVOLUTION OF PERSONAL COMPUTER DEVICES THROUGHOUT THE PC AGE A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science (Honours) in Software Engineering Ryan Abbott ST20074068 Supervisor: Paul Angel Department of Computing & Information Systems Cardiff School of Management Cardiff Metropolitan University April 2017 Declaration I hereby declare that this dissertation entitled A Study of the Growth and Evolution of Personal Computer Devices Throughout the PC Age is entirely my own work, and it has never been submitted nor is it currently being submitted for any other degree. Candidate: Ryan Abbott Signature: Date: 14/04/2017 Supervisor: Paul Angel Signature: Date: 2 Table of Contents Declaration .................................................................................................................................. 2 List of Figures ............................................................................................................................... 4 1. ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................ 5 2. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 6 3. METHODOLOGY.................................................................................................................... 8 4. LITERATURE REVIEW ............................................................................................................ -

Downloaded in Jan 2004; "How Smartphones Work" Symbian Press and Wiley (2006); "Digerati Gliterati" John Wiley and Sons (2001)

HOW OPEN SHOULD AN OPEN SYSTEM BE? Essays on Mobile Computing by Kevin J. Boudreau B.A.Sc., University of Waterloo M.A. Economics, University of Toronto Submitted to the Sloan School of Management in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASSACHUBMMIBE OF TECHNOLOGY Doctor of Philosophy at the AUG 2 5 2006 MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY LIBRARIES June 2006 @ 2006 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All Rights Reserved. The author hereby grn Institute of Technology permission to and to distribute olo whole or in part. 1 Signature ot Author.. Sloan School of Management 3 May 2006 Certified by. .............................. ............................................ Rebecca Henderson Eastman Kodak LFM Professor of Management Thesis Supervisor Certified by ............. ................ .V . .-.. ' . ................ .... ...... Michael Cusumano Sloan Management Review Professor of Management Thesis Supervisor Certified by ................ Marc Rysman Assistant Professor of Economics, Boston University Thesis Supervisor A ccepted by ........................................... •: °/ Birger Wernerfelt J. C. Penney Professor of Management Science and Chair of PhD Committee ARCHIVES HOW OPEN SHOULD AN OPEN SYSTEM BE? Essays on Mobile Computing by Kevin J. Boudreau Submitted to the Sloan School of Management on 3 May 2006, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Abstract "Systems" goods-such as computers, telecom networks, and automobiles-are made up of mul- tiple components. This dissertation comprises three esssays that study the decisions of system innovators in mobile computing to "open" development of their systems to outside suppliers and the implications of doing so. The first essay considers this issue from the perspective of which components are retained under the control of the original innovator to act as a "platform" in the system. -

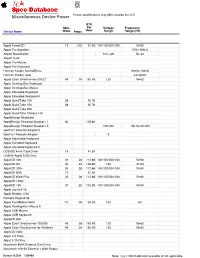

Miscellaneous Device Power Power Specifications May Differ Outside the U.S

Miscellaneous Device Power Power specifications may differ outside the U.S. BTU Max. Per Voltage Frequency Device Name Watts Amps Hour Range Range (Hz) Apple PowerCD 15 .125 51.30 100-125/200-240 50-60 Apple Pro Speakers 70Hz-20kHz Airport BaseStation 100–120 50–60 Airport Card Apple Pro Mouse Apple Pro Keyboard Harman Kardon SoundSticks 200Hz-15kHz Harman Kardon iSub 44-180Hz Apple Color OneScanner 600/27 45 .38 153.90 120 58-62 Apple Desktop Bus Keyboard Apple Desktop Bus Mouse Apple Extended Keyboard Apple Extended Keyboard II Apple QuickTake 100 28 95.76 Apple QuickTake 150 28 95.76 Apple QuickTake 200 Apple QuickTime Camera 100 AppleDesign Keyboard AppleDesign Powered Speakers I 40 136.80 AppleDesign Powered Speakers II 100-240 150 Hz-20 kHz GeoPort Telecom Adapter II GeoPort Telecom Adapter 5 Apple Adjustable Keyboard Apple Standard Keyboard Apple Standard Keyboard II DDS-DC 4mm Tape Drive 15 51.30 UniDisk-Apple 5.25 Drive AppleCD 300 33 .28 112.86 100-125/200-240 50-60 AppleCD SC 40 .33 136.80 120 47-64 AppleCD 300+ 33 .28 112.86 100-125/200-240 50-60 AppleCD 600i 15 51.30 AppleCD 600e Plus 33 .28 112.86 100-125/200-240 50-60 AppleCD 1200i AppleCD 150 30 .25 102.60 100-125/200-240 50-60 Apple Joystick //e Apple Modem 1200 Numeric Keypad IIe Apple Fax Modem 9600 10 .08 34.20 120 60 Apple Desktop Bus Mouse II Apple USB Mouse Apple USB Keyboard AppleCD 800 Apple Color OneScanner 1200/30 45 .38 153.90 120 58-62 Apple Color OneScanner for Windows 45 .38 153.90 120 58-62 AppleCD 300e Apple 3.5 Drive Apple 5.25 Drive Macintosh 800K External Disk Drive Macintosh HDI-20 External 1.4MB Floppy OCTOBER 15, 2016 12:58 AM Note: n/a = information not available or not applicable Miscellaneous Device Power Power specifications may differ outside the U.S. -

This Article Is About the Wireless Tablet Computer by Apple Inc. for the Retail Point-Of-Sale Device, See Fujitsu Ipad

Ipad This article is about the wireless tablet computer by Apple Inc. For the retail point-of-sale device, see Fujitsu iPAD. iPad An iPad showing its home screen Developer Apple Inc. [1] Manufacturer Foxconn (on contract) Type Tablet media player/PC Wi-Fi model (U.S.): April 3, 2010[2][3] Wi-Fi + 3G Model (U.S.): Release date April 30, 2010[4] Both Models (Nine more countries): May 28, 2010[5] Units sold 3 million (as of 22 June 2010)[6] Operating iOS 3.2.2 (build 7B500)[7] Released system August 11, 2010; 54 days ago Internal rechargeable non-removable Power 25 W·h (90 kJ) lithium-polymer battery[8] [8][9] CPU 1 GHz Apple A4 Storage Flash memory capacity 16GB, 32GB, or 64GB models only[8] 256 MB DRAM built into Apple A4 Memory package (top package of PoP contains two 128 MB dies)[10] 1024 × 768 px (aspect ratio 4:3), 9.7 in Display (25 cm) diagonal, appr. 45 in2 (290 cm2), 132 PPI, XGA, LED-backlit IPS LCD[8] Graphics PowerVR SGX 535 GPU[11] Multi-touch touch screen, headset controls, proximity and ambient light Input sensors, 3-axis accelerometer, magnetometer Camera None Wi-Fi (802.11a/b/g/n) Bluetooth 2.1 + EDR Wi-Fi + 3G model also includes: Connectivity UMTS / HSDPA (Tri band±850, 1900, 2100 MHz) GSM / EDGE (Quad band±850, 900, 1800, 1900 MHz) iTunes Store, App Store, MobileMe, Online services iBookstore, Safari 242.8 mm (9.56 in) (h) Dimensions 189.7 mm (7.47 in) (w) 13.4 mm (0.53 in) (d) Wi-Fi model: 680 g (1.5 lb) Weight Wi-Fi + 3G model: 730 g (1.6 lb)[8] Related articles iPhone, iPod touch (Comparison) Website www.apple.com/ipad The iPad is a tablet computer designed and developed by Apple.