Tees Valley Economic Assessment Is the Core Statistical Document Related to Economic Development in Tees Valley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drinking Establishments in TS13 Liverton Mines, Saltburn

Pattinson.co.uk - Tel: 0191 239 3252 drinking establishments in TS13 Single storey A4 public house Two bedroom house adjoining Liverton Mines, Saltburn-by-the-Sea Excellent development potential (STP) North Yorkshire, TS13 4QH Parking for 3-5 vehicles Great roadside position £95,000 (pub +VAT) Freehold title Pattinson.co.uk - Tel: 0191 239 3252 Summary - Property Type: Drinking Establishments - Parking: Allocated Price: £95,000 Description An end-terraced property of the pub, which is a single-storey construction under flat roofing. It is attached to a two-storey house, which is connected both internally and both have their own front doors. The pub main door is located at the centre of the property and leads into, on the right a Public Bar with pool area. To the left of the entrance is a Lounge Bar. Both rooms are connected by the servery, which has a galley style small kitchen in-between both rooms. There are Gents toilets in the Bar with Ladies toilets in the Lounge. Behind the servery are two rooms, one for storage the other being the beer cellar. We are informed that the two-storey house on the end elevation is also part of the property, but is in poor decorative order and is condemned for habitation. It briefly comprises Lounge, Kitchen and Bathroom on the ground floor and has two double bedrooms and a small box room on the first floor of the house only. The property would lend itself to be used for existing use or be developed for alternative use, subject to the required planning permissions. -

BRI 51 1 Shorter-Contributions 307..387

318 SHORTER CONTRIBUTIONS An Early Roman Fort at Thirkleby, North Yorkshire By MARTIN MILLETT and RICHARD BRICKSTOCK ABSTRACT This paper reports the discovery through aerial photography of a Roman fort at Thirkleby, near Thirsk in North Yorkshire. It appears to have two structural phases, and surface finds indicate that it dates from the Flavian period. The significance of its location on the intersection of routes north–south along the edge of the Vale of York and east–west connecting Malton and Aldborough is discussed in the context of Roman annexation of the North. Keywords: Thirkleby; Roman fort; Roman roads; Yorkshire INTRODUCTION The unusually dry conditions in northern England in the summer of 2018 produced a substantial crop of new sites discovered through aerial photography. By chance, the Google Earth satellite image coverage for parts of Yorkshire has been updated with a set of images taken on 1 July 2018, during the drought. Amongst the numerous sites revealed in this imagery – often in areas where crop-marks are rarely visible – is a previously unknown Roman fort (FIG.1).1 The site (SE 4718 7728) lies just to the west of the modern A19, on the southern side of the Thirkleby beck at its confluence with the Carr Dike stream, about 6 km south-east of Thirsk. It is situated on level ground at a height of about 32 m above sea level on the southern edge of the flood plain of the beck, which is clearly visible on the aerial images. A further narrow relict stream bed runs beside it to the south-east. -

Yorkshire GREEN Corridor and Preliminary Routeing and Siting Study

Yorkshire GREEN Project – Corridor and Preliminary Routeing and Siting Study Report Yorkshire GREEN Project Corridor and Preliminary Routeing and Siting Study (YG-NSC-00001) National Grid National Grid House Warwick Technology Park Gallows Hill Warwick CV34 6DA Final - March 2021 Yorkshire GREEN Project – Corridor and Preliminary Routeing and Siting Study Report Page intentionally blank Yorkshire GREEN Project – Corridor and Preliminary Routeing and Siting Study Report Document Control Document Properties Organisation AECOM Ltd Author Alison Williams Approved by Michael Williams Title Yorkshire GREEN Project – Corridor and Preliminary Routeing and Siting Study Report Document Reference YG-NSC-00001 Version History Date Version Status Description/Changes 02 March 2021 V8 Final version Yorkshire GREEN Project – Corridor and Preliminary Routeing and Siting Study Report Page intentionally blank Yorkshire GREEN Project – Corridor and Preliminary Routeing and Siting Study Report Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Overview and Purpose 1 1.2 Background and Need 3 1.3 Description of the Project 3 1.4 Structure of this Report 7 1.5 The Project Team 7 2. APPROACH TO ROUTEING AND SITING 8 2.1 Overview of National Grid’s Approach 8 2.2 Route and Site Selection Process 11 2.3 Overview of Stages of Development 11 3. THE STUDY AREA 16 3.1 Introduction 16 3.2 York North Study Area 16 3.3 Tadcaster Study Area 17 3.4 Monk Fryston Study Area 17 4. YORK NORTH OPTIONS APPRAISAL 19 4.1 Approach to Appraisal 19 4.2 CSEC Siting Area Identification 19 4.3 Substation Siting Area Identification 19 4.4 Overhead Line Routeing Identification 20 4.5 Combination Options 20 4.6 Screening of York North Options 24 4.7 Options Appraisal Summary of Remaining York North Options 28 4.8 The Holford Rules and Horlock Rules 76 4.9 York North Preferred Option 76 5. -

Middlesbrough Flyer (Aug 2015).Cdr

SPECIALIST STOP SMOKING SERVICE SESSIONS Middlesbrough 2015 West Middlesbrough Children's Centre Monday Stainsby Road, Whinney Banks, 13.00pm - 15.00pm Middlesbrough, TS5 4JS Starting Monday 1st June 2015 Lifestore Tuesday 10-12 Central Mall, The Mall, 10.00am - 14.00pm Middlesbrough TS1 2NR Community Hub 13.00pm - 14.30pm Wednesday Grove Hill, Bishopton Road, Middlesbrough, TS1 3JR Starting Wednesday 3rd June 2015 The Manor Hub 5.00pm - 7.00pm Manor Farm Way, Coulby Newham, Middlesbrough TS8 0TJ Friday Community Hub 9.30am - 11.00am Birkhall Road, Thorntree TS3 9JW Life Store Saturday 10-12 Centre Mall, The Mall, 10.00am - 12 noon Middlesbrough TS1 2NR GP PRACTICE STOP SMOKING SUPPORT Stop Smoking Support is also available from many GP practices - to find out if your GP practice provides this support, please contact the Specialist Stop Smoking Service on 01642 383819. No appointment needed for the above Specialist Stop Smoking Sessions. Please note that clients should arrive at least 20 minutes before the stated end times above in order to be assessed. Clinics are subject to changes - to confirm availability please ring the Specialist Stop Smoking Service on 01642 383819. Alternatively, if you have access to the internet, S L please visit our website 5 1 / 9 d for up-to-date stop smoking sessions: e t a d p www.nth.nhs.uk/stopsmoking u Middlesbrough Redcar & Cleveland t Middlesbrough Redcar & Cleveland s Stockton & Hartlepool a Stockton & Hartlepool L PHARMACY ONE STOP SHOPS Middlesbrough AC Moule & Co Pharmacy *P PJ Wilkinson Chemist -

Minerals and Waste Core Strategy

Tees Valley Joint Minerals and Waste Development Plan Documents In association with Core Strategy DPD Adopted September 2011 27333-r22.indd 1 08/11/2010 14:55:36 i ii Foreword The Tees Valley Minerals and Waste Development Plan Documents (DPDs) - prepared jointly by the boroughs of Darlington, Hartlepool, Middlesbrough, Redcar and Cleveland and Stockton-on-Tees - bring together the planning issues which arise from these two subjects within the sub-region. Two DPDs have been prepared. This Minerals and Waste Core Strategy contains the long-term spatial vision and the strategic policies needed to achieve the key objectives for minerals and waste developments in the Tees Valley. The separate Policies and Sites DPD, which conforms with it, identifies specific sites for minerals and waste development and sets out policies which will be used to assess minerals and waste planning applications. The DPDs form part of the local development framework and development plan for each Borough. They cover all of the five Boroughs except for the part within Redcar and Cleveland that lies within the North York Moors National Park. (Minerals and waste policies for that area are included in the national park’s own local development framework.) The DPDs were prepared during a lengthy process of consultation. This allowed anyone with an interest in minerals and waste in the Tees Valley the opportunity to be involved. An Inspector appointed by the Secretary of State carried out an Examination into the DPDs in early 2011. He concluded that they had been prepared in accordance with the requirements of the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004 and were sound. -

Redcar-Cleveland Flyer

SPECIALIST STOP SMOKING SERVICE SESSIONS Redcar & Cleveland 2015 Wednesday Redcar Library 14.30pm - 16.00pm Kirkleatham Street, Redcar TS10 1RT Sunnyfield House Friday Community Centre, Guisborough 13.00pm - 14.30pm TS14 6BA GP PRACTICE STOP SMOKING SUPPORT Stop Smoking Support is also available from many GP practices - to find out if your GP practice provides this support, please contact the Specialist Stop Smoking Service on 01642 383819. No appointment needed for the above Specialist Stop Smoking Sessions. Please note that clients should arrive at least 20 minutes before the stated end times above in order to be assessed. Clinics are subject to changes - to confirm availability please ring the Specialist Stop Smoking Service on 01642 383819. Alternatively, if you have access to the internet, please visit our website S L 5 1 / for up-to-date stop smoking sessions: 3 d e t www.nth.nhs.uk/stopsmoking a d p u Middlesbrough Redcar & Cleveland t Middlesbrough Redcar & Cleveland s Stockton & Hartlepool a Stockton & Hartlepool L PHARMACY ONE STOP SHOPS Redcar & Cleveland Asda Pharmacy *P Coopers Chemist 2 North Street South Bank New Medical Centre Middlesbrough TS6 6AB Coatham Road Redcar TS10 1SR Tel: 01642 443810 Tel: 01642 483861 Boots the Chemist Harrops Chemist High Street Normanby TS6 0NH 1 Zetland Road Loftus TS13 4PP Tel: 01287 640557 Tel: 01642 452777 Lloyds Pharmacy Boots Pharmacy 35 Ennis Road, Rectory Lane Guisborough TS14 7DJ Dormanstown Tel: 01287 632120 TS10 5JZ Tel: 01642 490964 Boots Guisborough Westgate 18 Westgate Guisborough -

Descendants of Robert Appleby

Descendants of Robert Appleby Robert Appleby Mary Dennison Mary Liddle b: Bef 2 Apr 1777 in Mickley In The Parish Of b: Abt 31 Jul 1774 in Staindrop, County Durham, b: Abt 1786 in St. Hilda, South Shields, County Kirkby Malzeard, Yorkshire, England. England. Durham, England. d: 1 Nov 1847 in Eryholme, North Yorkshire, m: 26 Dec 1801 in Stanwick St. John, Yorkshire, m: 13 May 1811 in Eryholme, North Yorkshire, England. England. England. bu: 4 Nov 1847 in St. Marys Church, Eryholme, d: 28 Aug 1809 in Eryholme, North Yorkshire, d: Abt 22 Nov 1857 in Thornaby-On-Tees, North North Yorkshire, England. England. Yorkshire, England. bu: Aug 1809 in Eryholme, North Yorkshire, bu: 22 Nov 1857 in Thornaby-On-Tees, North England. Yorkshire, England. Robert Appleby Elizabeth Robinson Jane Appleby John Parkinson Thomas Appleby Anthony Appleby Eleanor Newton John Appleby Elizabeth Johnson James Appleby Margaret Workman Henry Appleby Sarah Davison William Appleby b: Abt 17 Aug 1806 in Forcett Near Gainford, b: Abt 1811 in Marrick, Yorks, ENG b: Abt 10 Jul 1808 in Eryholme, North Yorkshire, b: Abt 12 Mar 1809 in South Cowton, North b: Bef 28 Jun 1812 in Eryholme, North Yorkshire, b: Bef 14 Aug 1814 in Eryholme, North Yorkshire, b: Abt 29 Aug 1813 in Saint Andrews, Bishop b: Bef 23 Feb 1817 in Eryholme, North Yorkshire, b: Abt 1 Oct 1826 in Hurworth On Tees, County b: Bef 14 May 1820 in Eryholme, North Yorkshire, b: Abt 1813 in Bongate, Westmoreland, England. b: Abt 18 Aug 1822 in Eryholme, North Yorkshire, b: Abt 1827 in Hudswell, Yorkshire, England. -

The Benefice Profile of Yarm with Kirklevington, Picton and Worsall

The Benefice Profile of Yarm with Kirklevington, Picton and Worsall St Mary Magdalene, Yarm Aerial photographs taken by Harry Brown All Saints, Worsall A message from the Rt Revd Paul Ferguson, Bishop of Whitby Welcome, and thank you for your interest in the post of Rector of Yarm with Kirklevington, Picton and Worsall. This post offers exciting possibilities for ministry in a varied town-and-country setting. As you will read in these pages, this is a benefice of two parishes comprising the market town of Yarm and a group of nearby villages. This relatively new grouping was formed under the leadership of the previous Rector, Canon John Ford, who was also Area Dean and who retired in 2020. The communities are conscious of their very long history — Yarm is an ancient fording place over the River Tees, and the villages have been the source of a wealth of Saxon and Anglo-Danish archaeology — but they are not in any sense locked into the past. Retail and education are key to their economy and culture; rural industry still has a significant part to play, and there is extensive new house-building and an increasing population. The new Rector will find a secure foundation to build on, willing and able lay leaders, and a shared commitment to worship well planned and led in a generally liberal Catholic style. Although there is mention in this profile of concern that congregations are ageing, in fact there is more involvement with families and younger people, and with external institutions, than would be found in many other places. -

Tees Valley Local Major Scheme Prioritisation Draft 3

Appendix 1 Tees Valley Local Major Scheme Prioritisation Draft 3 This note sets out the draft priority list for the Tees Valley’s 2015‐19 local major transport scheme budget, which has been devolved from central government. The management of this budget is explained in further detail within the Tees Valley Local Major Transport Schemes Assurance Framework. The process and the Tees Valley’s current position is summarised below: 1 Appendix 1 Scheme Identification and Sifting Scheme Identification A long list of highway and public transport schemes has been identified through the Tees Valley Area Action Plan (AAP). This has been achieved within the AAP by identifying congestion hotspots using the Tees Valley Multimodal Model. The model helps to predict where development and growth, specified within the Development Database, will contribute to future congestion on the Tees Valley’s Strategic Road Network. Numerous schemes are then tested within the model to identify which will mitigate these congestion hotspots and appropriate schemes are added to the long list. The long list of schemes has also been supplement by schemes identified by local authorities through work they have undertaken on a site by site basis. The model provides an assessment of each scheme and produces outputs that can be used within the sifting and prioritisation process. Sifting The sifting criteria have been selected so that any scheme that reaches the prioritisation phase would most likely be able to be developed into a WebTAG compliant business case with further work. The sifting criteria are: Value for Money: A Benefit Cost Ration (BCR) of greater than 1.5 Total Scheme Cost: Between £1.5m and £20m Timescale: A scheme would be deliverable within the funding period (2015‐19) and would provide sufficient benefits to offset its costs within 5 years of the end of the period. -

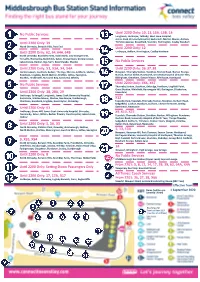

Middlesbrough Bus Station

No Public Services Until 2200 Only: 10, 13, 13A, 13B, 14 Longlands, Linthorpe, Tollesby, West Lane Hospital, James Cook University Hospital, Easterside, Marton Manor, Acklam, Until 2200 Only: 39 Trimdon Avenue, Brookfield, Stainton, Hemlington, Coulby Newham North Ormesby, Berwick Hills, Park End Until 2200 Only: 12 Until 2200 Only: 62, 64, 64A, 64B Linthorpe, Acklam, Hemlington, Coulby Newham North Ormesby, Brambles Farm, South Bank, Low Grange Farm, Teesville, Normanby, Bankfields, Eston, Grangetown, Dormanstown, Lakes Estate, Redcar, Ings Farm, New Marske, Marske No Public Services Until 2200 Only: X3, X3A, X4, X4A Until 2200 Only: 36, 37, 38 Dormanstown, Coatham, Redcar, The Ings, Marske, Saltburn, Skelton, Newport, Thornaby Station, Stockton, Norton Road, Norton Grange, Boosbeck, Lingdale, North Skelton, Brotton, Loftus, Easington, Norton, Norton Glebe, Roseworth, University Hospital of North Tees, Staithes, Hinderwell, Runswick Bay, Sandsend, Whitby Billingham, Greatham, Owton Manor, Rift House, Hartlepool No Public Services Until 2200 Only: X66, X67 Thornaby Station, Stockton, Oxbridge, Hartburn, Lingfield Point, Great Burdon, Whinfield, Harrowgate Hill, Darlington, (Cockerton, Until 2200 Only: 28, 28A, 29 Faverdale) Linthorpe, Saltersgill, Longlands, James Cook University Hospital, Easterside, Marton Manor, Marton, Nunthorpe, Guisborough, X12 Charltons, Boosbeck, Lingdale, Great Ayton, Stokesley Teesside Park, Teesdale, Thornaby Station, Stockton, Durham Road, Sedgefield, Coxhoe, Bowburn, Durham, Chester-le-Street, Birtley, Until -

Tees Tidal Flooding 5Th December 2013

Lead Local Flood Authority Flood Investigation Report Tees Tidal Flooding 5th December 2013 Final Report 2 Revision Schedule Document Date Author Draft 1.0 3/3/14 J L Salisbury Draft 2.0 20/3/14 J L Salisbury Final Report 26/3/14 J L Salisbury 3 4 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1.1. LLFA investigation 1.2. Stockton on Tees 1.3. Site Locations 1.3.1. Port Clarence 1.3.2. Billingham Reach Industrial Estate 1.3.3. Greatham Creek 1.3.4. A19 Portrack Interchange 1.3.5. A66 Teesside Park 2. History 2.1. Drainage history 2.1.1. Port Clarence 2.1.2. Billingham Reach Industrial Estate 2.1.3. Greatham Creek 2.1.4. A19 Portrack Interchange 2.1.5. A66 Teesside Park 3. Incident 3.1. Incident on 5th December 2013 3.2. Event data 4. Types of Flooding 4.1. Tidal Flooding 4.2. Main River flooding 4.3. Ordinary Watercourse Flooding 4.4. Sewerage Flooding 4.5. Highway Drainage 4.6. Culvert Issues 4.7. Run Off 5. Duties and Responsibilities 5.1. Lead Local Flood Authority 5.2. Stockton on Tees Borough Council 5.3. Environment Agency 5.4. Northumbrian Water 5.5. Highways Agency 5 5.6. Riparian Landowners 5.7. Residents 6. Flood Alleviation Scheme 7. Recommendations Appendices 1. Flood warning area 121FWT568 2. Flood warning area 121FWT557 3. Flood warning area 121FWT562 4. Location Plan of Greatham Creek Breach 5. Plan showing worst affected residential area in Port Clarence Glossary of Terms Useful Contacts Useful Links References 6 Executive Summary On Thursday 5th December 2013, the Borough of Stockton on Tees was again subject to severe flooding. -

Chairman's Report

TEES VALLEY LOCAL AC CESS FORUM ANNUAL REPORT 2014 - 2 0 1 5 Chairman’s Report The Heritage Lottery Funded Partner- The TVLAF is supporting steps to ex- ship programme, River Tees Re- tend the England Coast Path route discovered centering on the River Tees, from North Gare at Hartlepool across Appointing Authority was officially launched on the 17th the Tees Estuary to link with the Cleve- Membership March 2015 at Middlesbrough College. land Way. The Secretary of State has ‘Welcome Aboard’ was attended by opened the consultation on this stretch COUNCILLOR MICHAEL SMITH representatives from local business and during March 2015 linking North Gare industry, and senior leaders from the in Hartlepool, across the Newport STOCKTON ON TEES BOROUGH COUNCIL public and third sectors. The TVLAF Bridge to Middlesbrough and on to has played a key role in the develop- Filey Brigg in North Yorkshire. ment of this project, pulling together COUNCILLOR DOT LONG the relevant Officers and Volunteers DARLINGTON BOROUGH COUNCIL critical to the project’s success. Doug Nicholson, Chair of River Tees Rediscovered, said: “The River Tees is COUNCILLOR ALAN CLARK the greatest natural asset in the area HARTLEPOOL BOROUGH and this will be the first time it has COUNCIL been developed as a whole. We view this project as a real opportunity to change perceptions about our river and COUNCILLOR CHARLES our area, to look through fresh eyes at ROONEY the beauty and drama of the landscape MIDDLESBROUGH COUNCIL today and to celebrate this great asset Newport Bridge by courtesy of Malc McDonald at the heart of Teesside.’’ In 2009 the Limestone Landscapes Regional working has continued, with partnership began the current pro- joint work pledged between our gramme of works.