Filed an Amended Complaint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NH Bill Report March 19, 2021 NH Bill Report March 19, 2021

NH Bill Report March 19, 2021 NH Bill Report March 19, 2021 NH - HB10 relative to the rates of business profits tax and the business enterprise tax. Last Action: Retained in Committee (March 9, 2021) Primary Sponsor: Representative Sherman Packard (R) NH - HB20 establishing the Richard "Dick" Hinch education freedom account program. Last Action: Retained in Committee (February 18, 2021) Primary Sponsor: Representative Sherman Packard (R) NH - HB62 relative to continued in-network access to certain health care providers. Last Action: Minority Committee Report: Ought to Pass with Amendment # 2021-0067h (March 12, 2021) Primary Sponsor: Representative William Marsh (R) NH - HB62 relative to continued in-network access to certain health care providers. Last Action: Minority Committee Report: Ought to Pass with Amendment # 2021-0067h (March 12, 2021) Primary Sponsor: Representative William Marsh (R) NH - HB63 relative to the reversal or forgiveness of emergency order violations. Last Action: Division I Work Session: 03/09/2021 09:00 am Members of the public may attend using the following link:To join the webinar: https://www.zoom.us/j/94444579237 (March 4, 2021) Primary Sponsor: Representative Andrew Prout (R) NH - HB68 relative to the definition of child abuse. Last Action: Committee Report: Inexpedient to Legislate (Vote 15-0; CC) (February 23, 2021) Primary Sponsor: Representative Dave Testerman (R) NH - HB79 relative to town health officers. Last Action: Committee Report: Ought to Pass (Vote 17-1; CC) (February 25, 2021) Primary Sponsor: Representative William Marsh (R) NH - HB89 adding qualifying medical conditions to the therapeutic use of cannabis law. Last Action: Committee Report: Ought to Pass with Amendment # 2021-0437h (Vote 20-0; CC) (March 2, 2021) Primary Sponsor: Representative Suzanne Vail (D) NH Bill Report March 19, 2021 NH - HB90 allowing alternative treatment centers to acquire and use in manufacturing hemp-derived cannabidiol (CBD) isolate. -

2014 Families First Voter Guide

2014 Families First Voter Guide About the 2014 guide to the New Hampshire primary Contents: election: Find your legislator………….............. 2-6 Cornerstone Action provides this information to help you NH Executive Council Pledge…………7 select the candidates most supportive of family-friendly NH State Senate Scores……...............7,8 policies including the right to life, strong marriages, and choice in education, sound fiscal management, and NH Representative’s Scores…….….8-29 keeping New Hampshire casino-free. NH Delegate Pledge Signers……...29, 30 What's in the guide and how we calculated the ratings : Where a candidate is a former state representative who left Cornerstone invited all candidates to sign the Families First office after the 2012 election, we provide their Cornerstone Pledge. We have indicated on this guide who has signed the voter guide score for 2012. Likewise, if an incumbent had pledge without candidate having modified it in any way. insufficient data from this year's votes, we have provided the 2012 score if available. Voting records are drawn from the 2014 legislative session, for incumbent state legislators running for re-election. We We encourage you to look beyond the scores and consider a include results from three Senate votes and eight House candidate's particular votes. You can contact candidates to votes. thank them for past votes, or to ask about disappointing ones or gaps in the record. Let them know what matters to you as A candidate's percentage mark is for votes cast in 2014. you consider your options at the polls. There is no penalty for an excused absence from a vote; however, an unexcused absence or “not voting" is penalized This guide will be updated as more candidate replies are by being included as a "no" vote. -

Senate Dems Newsletter

A P R I L 2 3 , 2 0 2 1 : I S S U E # 1 5 LEGISLATIVE WRAP UP S E N A T E D E M O C R A T S W E E K L Y N E W S L E T T E R This week, Welcome! we're looking at: S E N A T E C O N T I N U E S R E M O T E W e e k i n R e v i e w A C T I V I T Y N e x t W e e k ' s H e a r i n g s This week Senate Committees continued to I n t h e N e w s meet remotely via Zoom. The Senate will meet in session on Thursday beginning at 10AM. To sign in to speak, register your position, and/or submit testimony, please visit: http://gencourt.state.nh.us/remotecommittee /senate.aspx Week in Review This week we're joined by Senator Cindy Rosenwald to discuss the budget and HB 544 Senate Democratic Leader on Derek Chauvin Trial April 20th Following the jury verdict that Derek Chauvin had been found guilty on all three charges in the death of George Floyd, Senate Democratic Leader Donna Soucy (D-Manchester) released the following statement: “What happened today does not bring George Floyd back to his family. It does not erase where we have been, but it is a critical step forward towards what this nation can become. -

Senate Rules Committee Votes to Consolidate Bills Bipartisan Agreement Will Streamline Legislation in 2021

New Hampshire Senate NEWS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: December 21, 2020 CONTACT: Carole Alfano, 603.496.0412 Senate Rules Committee votes to consolidate bills Bipartisan agreement will streamline legislation in 2021 CONORD, NH – On a 6-0 vote, members of the Senate Rules Committee today agreed to consolidate all bills for the coming session into categories, clearing the way for better facilitation when public hearings are held remotely beginning in January. Senators called the bi-partisan accomplishment a “great collaboration”. Chairman Jeb Bradley (R-Wolfeboro) thanked all 24 senators for their willingness to participate in the process and staffers who worked so diligently to the organize some 250 bills. He said, “We may not agree on the content of every bill, but I believe the process that the Select Committee on Legislation undertook to categorize all of the proposed legislation was fair and inclusive.” Bradley also thanked Senators Sharon Carson and Cindy Rosenwald as well as bipartisan senate staffers whose expertise was” indispensable in the process." Sen. Donna Soucy (D- Manchester) emphasized the collaborative process and thanked her fellow senators for their input by adding, “By consolidating bills, we will be able to move forward with an efficient session that focuses on the immediate and long-term needs of the state.” The committee members agreed that senators will still have the option for a bill to be considered as a “stand alone” if that is their preference. However, due to consolidation, bills will have one designated sponsor, instead of individuals. The committee stressed they will work with the Office of Legislative Services to ensure that all senators who sponsored legislation that was consolidated are given credit for the bill. -

January 16, 2018 Chris Sununu Governor of New Hampshire 107

January 16, 2018 Chris Sununu Jeb Bradley Governor of New Hampshire New Hampshire Senate Majority Leader 107 North Main Street 107 North Main Street Concord, NH 03303 Concord, NH 03303 Chuck Morse Gene Chandler New Hampshire Senate President New Hampshire Speaker of the House 107 North Main Street 107 North Main Street Concord, NH 03303 Concord, NH 03303 Dear Governor Sununu, Senator Morse, Senator Bradley, and Speaker Chandler, In the coming months, the New Hampshire legislature will be responsible for reauthorizing our state's Medicaid Expansion, the New Hampshire Health Protection Plan, a program that currently covers more than 50,000 Granite Staters. Medicaid Expansion provides vital services to those who wouldn’t be able to afford health insurance on their own. It also plays a crucial role during the opioid crisis, with more than 20,000 Granite Staters having accessed Substance Use Disorder treatment services through the program. It is vital that Republicans and Democrats alike come together and reauthorize a clean version of Medicaid Expansion. Our objective is simple: reauthorize Medicaid Expansion so that nobody loses their health insurance. Every single one of those more than 50,000 New Hampshire residents who rely on the program for quality care must be able to continue to rely on this program after the reauthorization. That is our bottom line and fundamental guarantee. This should be a simple decision for New Hampshire Republicans, who have pledged to work to reauthorize the program as well. Hopefully Republicans join us in the understanding that any reauthorization that kicks people off of insurance isn’t really reauthorization at all; it’s a partial repeal and that is simply unacceptable. -

New Hampshire General Election Voter Guide 2020

New Hampshire General Election Voter Guide 2020 Statewide polls conducted in 2017 and 2019 have found that 68% of Granite Staters support ending cannabis prohibition. With public support now overwhelmingly in favor of reform, there has never been a more important opportunity to move New Hampshire forward on cannabis policy than this year’s elections for governor, state senator, and state representative. The 2020 general election is scheduled for Tuesday, November 3. Please note that if you have any concerns about voting in light of COVID-19, the state has made it clear that you may choose to register and vote by absentee ballot. Color key: Green = supports legalizing cannabis for adults’ use Orange = unknown, uncertain, or less supportive Red = opposed or much less supportive Voter Guide Highlights: Republican Gov. Chris Sununu signed the decriminalization bill into law in 2017, and he also signed bills adding chronic pain and PTSD as qualifying conditions for medical cannabis. However, he vetoed a medical cannabis home cultivation bill in 2019, and on October 5 he once again dismissed the idea of legalizing cannabis saying, "now is just not the time." (website) The Democratic nominee for governor, state Sen. Dan Feltes, supports legalizing, regulating, and taxing cannabis for adults’ use. According to an article in The Concord Monitor, Feltes says he supports legalization and regulation under certain “eminently achievable conditions” such as “no gummies.” After the September 8 primary, he publicly endorsed the legalization plan that had been put forward by his opponent. (website) The Libertarian candidate for governor, Darryl Perry, is a longtime supporter of cannabis legalization. -

Political Contributions & Related Activity Report

Political Contributions & Related Activity Report 2012 CARTER BECK JACKIE MACIAS ALAN ALBRIGHT SVP & Counsel VP & General Manager Legal Counsel to WellPAC Medicaid JOHN JESSER VP, Provider Engagement & GLORIA MCCARTHY JOHN WILLEY COC EVP, Enterprise Execution & Sr. Director, Efciency Government Relations 2012 WellPAC DAVID KRETSCHMER WellPAC Treasurer SVP, Treasurer & Chief MIKE MELLOH Investment Ofcer VP, Human Resources TRACY WINN Board of Directors Manager, Public Affairs ANDREW MORRISON DEB MOESSNER WellPAC Assistant Treasurer & SVP, Public Affairs President & General Manager Executive Director WellPAC Chairman KY 1 from the Chairman America’s health care system is in the midst of transformative change, and WellPoint is leading the way by making it easier for consumers to access and use it while improving the health of the people we serve. In this new post-reform era, WellPoint’s Public Affairs function is more important than ever as the government expands its regulatory scope into our key lines of business. By 2015, almost 66 percent of the company’s revenue will be paid either in part or entirely by the federal and state government. For this reason, we continue to play an active role in the political process through our Public Affairs efforts, industry memberships and WellPAC, our political action committee. More than 1,875 WellPoint associates provided voluntary nancial support to WellPAC in 2012. Their generosity allowed our PAC to make contributions of more than $780,000 to federal campaigns and $140,000 to state and local campaigns on both sides of the political aisle in 2012. Our participation in the political process helps us develop good working relationships with Members of Congress, as well as key state legislators, in order to communicate WellPoint’s perspective on a range of issues including the cost and quality of today’s health care, the establishment of insurance exchanges and the expansion of Medicaid. -

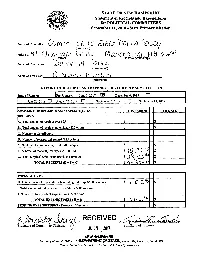

Soucy - Combined 1.Pdf

STATE OF NEW HAMPSIDRE Statement ofReceipts and Expenditures for POLITICAL COMMITTEES CC September 11, 2018 - State Primary Election Name of Committee c0 m m I ti ee.._ t 0 E.\~~,.. :Do() nO\ Et::Dcv (print name) Address: 9 \ fr \ e..x C1 n cJ u '})( \\( L M QYJCbes-r tc N }J 03 \D£1 (street) (town/city/state/zip) Name of Chairperson: ]){!) rlO{) m &uS!::fe (print n e) NameofTreasurer: B\ CkJD.Cd 6un\Lf£ (print name) REPORT OF RECEIPTS AND EXPENDITURE FOR PRIMARY ELECTION D December 6, 2017 D June 20, 2018 D tember 5, 2018 D Se tember 19, 2018 D SUMMARY OF RECEIPTS AND EXPENDITURES THIS PERIOD TO DATE RECEIPTS A. Total amount of receipts over $25 $ 2.'i, ~1 $ B. Total amount of receipts unitemized ($25 or less) $ ~50 $ C. Number of Contributors I 06 D. Number of receipts unitemized ($25 or less) f(o E. Subtotal of non-monetary (in-kind) receipts $ $ F. Subtotal of monetary receipts ( A + B - E) $ :J..Lf ~~I()(. $ \ lti ,10 >57 G. Total Surplus/Deficit from previous campaign- should be reported once (on the first report filed for the 20 18 election cycle) $ $ 67 TOTAL RECEIPTS (E + F +G) $ J,J.! lu k-7.00 $ I \6 11 t., . EXPENDITURES H. Total amount of expenditures (excluding Ind. Exp. $500 or more) $ \ I. Total amount of Independent Ex enditures $500 or more J. Number oflndependent Expenditures $500 or more TOTAL EXPENDITURES ( H +I) PENDING EXPENDITURES- Promise of Payment $ $ RECEIVED AUG 2 2 2018 Signature of Treasurer Secretary ofState's Office, I ort Main Street, State House, Room 204, Concord, NH 03301 Phone: 603-271-3242 --Fax: 603-271-6316-- http://sos.nh.gov Donna Soucy- 8/22/2018 Contributions ~name --~ployer IEmployerAddresstSt.~- AIG Claims, Inc •••~ t.- - -• t • -•-L --- ~~~ Almy js_~:-~~an j266 Poverty Lane !Lebanon INH 03766j 6/lS/181 $ 2SO.OO I I Retired I Retired Lebanon NH I 03766 Anheuser Busch It Busch Place 1st Louis IMO 631181 7/27/181 $ 2SO.OO Bakolas I Arthur 1247 Whitford St. -

Senate Districts

Senate Districts D A A Legend N A Senate District Names C Dist 01 - Sen. Erin Hennessey PITTSBURG Dist 02 - Sen. Bob Giuda Dist 03 - Sen. Jeb Bradley ³ Dist 04 - Sen. David Watters CLARKSVILLE ATKINSON & GILMANTON Dist 05 - Sen. Suzanne Prentiss ACADEMY GRANT STEWARTSTOWN Dist 06 - Sen. James Gray DIXS GRANT COLEBROOK DIXVILLE SECOND Dist 07 - Sen. Harold French COLLEGE GRANT WENTWORTHS LOCATION Dist 08 - Sen. Ruth Ward COLUMBIA ERVINGS Dist 09 - Sen. Denise Ricciardi LOC MILLSFIELD ERROL Dist 10 - Sen. Jay Kahn ODELL STRATFORD Dist 11 - Sen. Gary Daniels CAMBRIDGE Dist 12 - Sen. Kevin Avard DUMMER Dist 13 - Sen. Lucinda Rosenwald STARK MILAN N OR Dist 14 - Sen. Sharon Carson TH UM BE RL AN Y D N N SUCCESS E Dist 15 - Sen. Becky Whitley K IL K BERLIN LANCASTER Dist 16 - Sen. Kevin Cavanaugh 1 Dist 17 - Sen. John Reagan GORHAM JEFFERSON RANDOLPH DALTON Dist 18 - Sen. Donna Soucy WHITEFIELD SHELBURNE T LITTLETON AN MARTINS GR S LOC NK BA UR Dist 19 - Sen. Regina Birdsell B & GREENS CARROLL OW L C THOMPSON & GRANT BEANS PURCHASE H MESERVES PUR MONROE A S N D S R D O M F L W E A T A S E LYMAN R A H N H R Dist 20 - Sen. Lou D'Allesandro C C A R K U S E R P IN S G P P A U H LISBON R C BETHLEHEM . R BEANS T U N GRANT P SUGAR A Dist 21 - Sen. Rebecca Perkins Kwoka R S HILL G T N S E T T G U R BATH FRANCONIA C A JACKSON S Dist 22 - Sen. -

FISCAL COMMITTEE of the GENERAL COURT MINUTES May 28, 2020

FISCAL COMMITTEE OF THE GENERAL COURT MINUTES May 28, 2020 The Fiscal Committee of the General Court met on Thursday, May 28, 2020 at 10:00 a.m. via audio conference. Members in attendance were as follows: Representative Mary Jane Wallner, Chairman Representative Ken Weyler Representative Susan Ford Representative Lynne Ober Representative Peter Leishman Representative David Huot (Alternate) Representative Patricia Lovejoy (Alternate) Representative Erin Hennessey (Alternate) Senator Lou D’Allesandro Senate President Donna Soucy Senator Jay Kahn Senator Cindy Rosenwald Senator Chuck Morse The audio conference convened at 10:05 a.m., with the assistance of Fallon Reed at the Department of Safety and Michael Kane, Legislative Budget Assistant. OFFICIAL AUDIO CONFERENCE MEETING PROCEDURES: The Chair opened the meeting with the following Right-to-Know checklist; “Due to the state of emergency declared by the Governor as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, and in accordance with the Governor's Emergency Order #12, pursuant to Executive Order 2020-04, as extended pursuant to Executive Order 2020-09, a public body is authorized to meet electronically. Please note that there is no physical location to observe and listen contemporaneously to this meeting which was authorized pursuant to the Governor's Emergency Order.” “However, in accordance with the Emergency Order, I am confirming that; 1) we are providing the public access to the meeting by telephone, with additional access possible by video or other electronic means. We are utilizing VAST -

U.S. Senate *Denotes Incumbent DISTRICT DEMOCRAT

2020 New Hampshire Primary Election Candidates Tuesday, September 8, 2020 U.S. Senate *Denotes Incumbent DISTRICT DEMOCRAT REPUBLICAN Jeanne Shaheen, Madbury* Bryant “Corky” Messner, Wolfeboro U.S. House of Representatives *Denotes Incumbent DISTRICT DEMOCRAT REPUBLICAN 1 Chris Pappas, Manchester* Matt Mowers, Bedford 2 Ann McLane Kuster, Hopkinton* Steven Negron, Nashua New Hampshire Governor *Denotes Incumbent Note: As of 7:30 a.m., Dan Feltes leads Andru Volinsky 63,793 to 60,904 DISTRICT DEMOCRAT REPUBLICAN Dan Feltes, Concord Chris Sununu, Newfields* Andru Volinsky, Concord New Hampshire Executive Council *Denotes Incumbent Note: As of 7:30 a.m., Cinde Warmington leads Leah Plunkett 8,392 to 7,538 Jim Beard leads Stewart Levenson 9,171 to 8,107 Janet Stevens leads Bruce Crochetiere 10,350 to 8,589 DISTRICT DEMOCRATS REPUBLICANS 1 Michael Cryans, Hanover* Joseph Kenney, Wakefield 2 Leah Plunkett, Concord Jim Beard, Lempster Cinde Warmington, Concord Stewart Levenson, Hopkinton 3 Mindi Messmer, Rye Bruce Crochetiere, Hampton Falls Janet Stevens, Rye 4 Mark Mackenzie, Manchester Ted Gatsas, Manchester* 5 Debora Pignatelli, Nashua* David Wheeler, Milford New Hampshire State Senate *Denotes Incumbent DISTRICT DEMOCRATS REPUBLICANS 1 Susan Ford, Easton Erin Hennessey, Littleton 2 Bill Bolton, Plymouth Bob Giuda, Warren* 3 Theresa Swanick, Effingham Jeb Bradley, Wolfeboro* 4 David Watters, Dover* Frank Bertone, Barrington 5 Suzanne Prentiss, Lebanon Timothy O’Hearne, Charlestown 6 Christopher Rice, Rochester James Gray, Rochester* 7 Philip -

Americans for Prosperity Foundation-New Hampshire Is Pleased to Present Our 2014 Legislative Score Card

2014 KEY VOTE SCORECARD Dear New Hampshire Taxpayer: Americans For Prosperity Foundation-New Hampshire is pleased to present our 2014 Legislative Score Card. AFP Foundation hopes that this Score Card will aid you in your e!orts to remain well informed regarding some of the key legislative activity that took place in Concord over this past year. While 2014 was not a budget year, there were many issues that impact the long-term financial future of New Hampshire, such as expanding the state’s Medicaid program under the A!ordable Care Act, increasing the gas tax and e!orts to pass a Right to Work law. These are critical issues that will shape our state for years to come. Within this Score Card you will find these votes and many others that are essential to ensuring free markets, entrepreneurship and opportunity. We hope this helps you see a clear picture of how legislators performed in these important areas. In addition to information on how your state legislators voted on important pieces of legislation, you will find included in this Score Card their contact information. AFP Foundation hopes you will use it to reach out to your State Senator and State Representatives and engage them on the issues that impact you and your family and our state. Sincerely, Greg Moore State Director AFP Foundation-NH About Americans for Prosperity Foundation Americans for Prosperity Foundation (AFPF) is a nationwide organization of citizen-leaders committed to advancing every individual’s right to economic freedom and opportunity. AFPF be- lieves reducing the size and intrusiveness of government is the best way to promote individual productivity and prosperity for all Americans.