1. UNDERSTANDING of the PROJECT REQUIREMENTS Austral Understands That the Project Will Be Assessed Under Part 4 of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Linking the Illawarra. Improving the Region's Transport

LINKING THE ILLAWARRA Improving the region’s transport connectivity Thinking business Disclaimer This report has been prepared by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) at the request of the Illawarra Business Chamber (IBC) in our capacity as advisors in accordance with the Terms of Reference and the Terms and Conditions contained in the Consultant Agreement between the IBC and PwC. The information, statements, statistics and commentary (together the ‘Information’) contained in this report have been prepared by PwC from publicly available material and from discussions held with the IBC. PwC may in their absolute discretion, but without being under any obligation to do so, update, amend or supplement this document. PwC have based this report on information received or obtained, on the basis that such information is accurate and, where it is represented by the client and other stakeholders as such, complete. The Information contained in this report has not been subject to an Audit. The Information must not be relied on by third parties, copied, reproduced, distributed, or used, in whole or in part, for any purpose other than detailed in our Consultant Agreement without the written permission of the IBC and PwC.1 Illawarra Business Chamber 1 Liability limited by a scheme approved under Professional Standards Legislation Illawarra Business Chamber PwC i Foreword A recent survey of members of the Illawarra Business Chamber (IBC) found that over 95% of businesses want to see better transport links to Sydney. Inefficiencies in transport links drive up the costs of doing business in the Illawarra and compromise future opportunities for market expansion. There are strong concerns that without effective planning and action now to address this issue, the projected expansion in the passenger and freight movement task over the next 20 years will see the transport and logistics costs for business increase significantly. -

Mt Keira Summit Park PLAN of MANAGEMENT December 2019

Mt Keira Summit Park PLAN OF MANAGEMENT December 2019 The Mt Keira Summit Park Plan of Management was prepared by TRC Tourism Pty Ltd for Wollongong City Council. Acknowledgements Images used in this Plan are courtesy of Wollongong City Council, Destination Wollongong and TRC Tourism except where otherwise indicated. Acknowledgement of Country Disclaimer Wollongong City Council would like to show their Any representation, statement, opinion or advice, respect and acknowledge the traditional expressed or implied in this document is made in good custodians of the Land, of Elders past and present, faith but on the basis that TRC Tourism Pty. Ltd., and extend that respect to other Aboriginal and directors, employees and associated entities are not Torres Strait Islander people. liable for any damage or loss whatsoever which has occurred or may occur in relation to taking or not taking action in respect of any representation, statement or advice referred to in this document. ©Copyright TRC Tourism Pty Ltd www.trctourism.com Contents 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Purpose of the Plan of Management ............................................................................................ 2 1.3 Making of the Plan of Management ............................................................................................ -

Wagga Wagga Australia

OPENING NIGHT THE MAN WHO KNEW INFINITY FRIDAY 11 MARCH 7PM Directed by Matthew Brown | UK | In English and Tamil with English subtitles | 108 mins | PG SELECTED: TORONTO & DUBAI FILM FESTIVAL 2015 Based on the inspirational biography of a genuine mathematical genius in the early twentieth century, The Man Who Knew Infinity tells the life story of Srinivasa Ramanujan (Dev Patel, Slumdog Millionaire). Image: Mustang From an underprivileged upbringing in Madras, India, Ramanujan earns admittance to Cambridge University during WWI, where he becomes a pioneer in mathematical theories. Academy Award-winner Jeremy Irons delivers a terrific performance as Cambridge University Professor G.H. Hardy, who is inspired and captivated by the mathematician’s ground-breaking theories. Their friendship transcends race and culture through mutual respect and understanding, and Ramanujan’s visionary theories shine through the ignorance and prejudice of those around him. WAGGA WAGGA “Tells such a good story, it’s hard to resist.” – SCREEN DAILY “Highly engaging performances…an extraordinary story.” – THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER FORUM 6 CINEMAS Followed by complimentary Opening Night drinks and party. 11-13 MARCH 2016 SPECIAL SCREENING: SUBSCRIBE HOW CALL ME DAD AND SAVE TO BOOK SATURDAY 12 MARCH 10.30AM Save over 35% on regular ticket Book tickets online in advance at Directed by Sophie Wiesner | Australia | In English | 80 mins | M prices with a subscription - all sff.org.au/Wagga. The Travelling Film Festival and Good Pitch Australia present a special screening of Australian nine films for only $9 per film ($8 documentary, Call Me Dad, a story about men who have perpetrated, or are at risk of concession), including Opening For ticket enquiries please perpetrating, family violence. -

Albion Park & Kiama District

Bus Route Numbers Look for bus Albion Park Stockland Shellharbour to Kiama via numbers 71 Dunmore, Minnamurra, Kiama Downs & & Kiama Bombo. Service operates Monday–Saturday. District Shellharbour to Albion Park via Flinders & 71 Buses Serving 76 Warilla. Service operates 7 days. 76 Albion Park Stockland Shellharbour to Albion Park via Oak Flats 77 Oak Flats & Albion Park Rail. Warilla Service operates Monday–Saturday. 77 Flinders Shellharbour Minnamurra Kiama See back cover for detailed route descriptions Price 50c Effective from 11 October 2010 Additional Services There are additional services operating in this area. Region 10 Please call 131500 or visit Transport Info for details. Wollongong This service is operated by 13-23 Investigator Drive Your Outer Metropolitan Unanderra NSW 2526 Region 10 operator Ph: 4271 1322 www.premierillawarra.com.au ABN: 27 080 438 562 Premier Illawarra Timetable 71/76/77 | Version 6 | 11 October 2010 Kiama Route Shellharbour to Kiama 71 via Dunmore, Minnamurra, Kiama Downs & Bombo Monday to Friday map ref Route 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 am am am pm pm pm pm pm A Shellharbour (Stockland) .... 9.10 10.40 12.10 1.40 2.40 4.25 5.30 B Dunmore (Princes Hwy & Riverside Dr) .... 9.20 10.50 12.20 1.50 2.50 4.35 5.40 C Kiama Downs (Barton Dr & McBrien Dr) 8.26 9.26 10.56 12.26 1.56 2.56 4.41 5.46 D Minnamurra (Public School) 8.34 9.34 11.04 12.34 2.04 3.04 4.49 5.54 E Kiama Downs (North Kiama Dr & Riverside Dr) 8.43 9.43 11.13 12.43 2.13 3.13 4.58 6.02 F Kiama Leisure Centre 8.50 9.50 11.20 12.50 2.20 3.20 5.05 6.08 G Kiama Hospital (Bonaira St) 8.56 9.56 11.26 12.56 2.26 3.26 5.11 6.13 Saturday map ref Route 71 71 71 71 am am pm pm A Shellharbour (Stockland) ... -

Faculty of Engineering December 2007

University o f Wollong ong FACULTY OF ENGINEERING DECEMBER 2007 Dean’s Spot At this time of the year our academic lives. For Faculty hosts large numbers of example, in addition high school students who are to abilities in maths, The Faculty of trying to choose their career science and lan- Engineering and to decide what University guages, we are look- course and which University to ing for any examples would like to enrol in for 2008. Naturally we of leadership, crea- wish all its staff think that Engineering and tive, and imaginative Physics at University of Wollongong or other skills students may and students a offers a wide variety of challenging and have demonstrated. This may Merry Christmas worthwhile careers and so we are very be apparent in non academic and a Happy keen to convince as many students as areas such as sport, music, possible to come to our Faculty. Hence debating, social or other ac- New Year! we run an innovative and comprehensive tivities, either within school or ‘Early Entry’ program. outside of school. We are interested in each student as a com- high school students in their final year at This program was pioneered by Engi- plete person, as this is important in school. neering at Wollongong over 10 years ago, establishing whether or not someone and has now been adopted by most other The early entry program is a wonderful is likely to become a good engineer. Faculties here, and even by other Univer- team effort of staff and students from all sities, such as University of New South So far this year we have interviewed parts of the Faculty and everyone in- Wales, who introduced their own early over 300 people interested in joining volved is impressed with the enthusiasm entry scheme last year. -

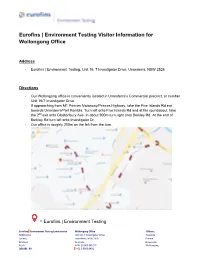

Environment Testing Visitor Information for Wollongong Office

Eurofins | Environment Testing Visitor Information for Wollongong Office Address - Eurofins | Environment Testing, Unit 16, 7 Investigator Drive, Unanderra, NSW 2526 Directions - Our Wollongong office is conveniently located in Unanderra’s Commercial precinct, at number Unit 16/7 Investigator Drive. - If approaching from M1 Princes Motorway/Princes Highway, take the Five Islands Rd exit towards Unanderra/Port Kembla. Turn left onto Five Islands Rd and at the roundabout, take the 2nd exit onto Glastonbury Ave. In about 900m turn right onto Berkley Rd. At the end of Berkley Rd turn left onto Investigator Dr. - Our office is roughly 200m on the left from the turn. = Eurofins | Environment Testing Eurofins Environment Testing Laboratories Wollongong Office Offices : Melbourne Unit 16, 7 Investigator Drive Adelaide Sydney Unanderra, NSW 2526 Darwin Brisbane Australia Newcastle Perth ABN: 50 005 085 521 Wollongong QS1081_R0 +61 2 9900 8492 Parking - There are 3 car spaces directly in front of the building, if the spaces are all occupied there is also on street parking out the front of the complex. General Information - The Wollongong office site includes a client services room available 24 hours / 7 days a week for clients to drop off samples and / or pick up bottles and stock. This facility available for Eurofins | Environment Testing clients, is accessed via a coded lock. For information on the code and how to utilize this access service, please contact Elvis Dsouza on 0447 584 487. - Standard office opening hours are between 8.30am to 5.00pm, Monday to Friday (excluding public holidays). We look forward to your visit. Eurofins | Environment Testing Management & Staff Eurofins Environment Testing Laboratories Wollongong Office Offices : Melbourne Unit 16, 7 Investigator Drive Adelaide Sydney Unanderra, NSW 2526 Darwin Brisbane Australia Newcastle Perth ABN: 50 005 085 521 Wollongong QS1081_R0 +61 2 9900 8492 . -

Guide to Cycling in the Illawarra

The Illawarra Bicycle Users Group’s Guide to cycling in the Illawarra Compiled by Werner Steyer First edition September 2006 4th revision August 2011 Copyright Notice: © W. Steyer 2010 You are welcome to reproduce the material that appears in the Tour De Illawarra cycling guide for personal, in-house or non-commercial use without formal permission or charge. All other rights are reserved. If you wish to reproduce, alter, store or transmit material appearing in the Tour De Illawarra cycling guide for any other purpose, request for formal permission should be directed to W. Steyer 68 Lake Entrance Road Oak Flats NSW 2529 Introduction This cycling ride guide and associated maps have been produced by the Illawarra Bicycle Users Group incorporated (iBUG) to promote cycling in the Illawarra. The ride guides and associated maps are intended to assist cyclists in planning self- guided outings in the Illawarra area. All persons using this guide accept sole responsibility for any losses or injuries uncured as a result of misinterpretations or errors within this guide Cyclist and users of this Guide are responsible for their own actions and no warranty or liability is implied. Should you require any further information, find any errors or have suggestions for additional rides please contact us at www.ibug,org.com Updated ride information is available form the iBUG website at www.ibug.org.au As the conditions may change due to road and cycleway alteration by Councils and the RTA and weather conditions cyclists must be prepared to change their plans and riding style to suit the conditions encountered. -

Listing and Sitting Arrangements, Nsw Local Court

LISTING AND SITTING ARRANGEMENTS, NSW LOCAL COURT Listing and sitting arrangements of the NSW Local Court Click on the links below to find the listing and sitting arrangements for each court. CHAMBER DAYS – Please note that Chamber Days have been cancelled from August 2020 to March 2021 to allow for the listing of defended work Albion Park Broken Hill Deniliquin Albury Burwood Downing Centre Armidale Byron Bay Dubbo Assessors - Small Claims Camden Dunedoo Ballina Campbelltown Dungog Bankstown Campbelltown Children's Eden Batemans Bay Casino Fairfield Bathurst Central Finley Bega Cessnock Forbes Bellingen Cobar Forster Belmont Coffs Harbour Gilgandra Bidura Children's Court Commonwealth Matters - Glen Innes (Glebe) (see Surry Hills see Downing Centre Gloucester Children’s Court) Condobolin Gosford Blayney Cooma Goulburn Blacktown Coonabarabran Grafton Boggabilla Coonamble Grenfell Bombala Cootamundra Griffith Bourke Corowa Gulgong Brewarrina Cowra Broadmeadow Children's Gundagai Crookwell Court Circuits Gunnedah 1 LISTING AND SITTING ARRANGEMENTS, NSW LOCAL COURT Hay Manly Nyngan Hillston Mid North Coast Children’s Oberon Court Circuit Holbrook Orange Milton Hornsby Parkes Moama Hunter Children’s Court Parramatta Circuit Moree Parramatta Children’s Court Illawarra Children's Court Moruya Peak Hill (Nowra, Pt. Kembla, Moss Moss Vale Vale and Goulburn) Penrith Mt Druitt Inverell Picton Moulamein Junee Port Kembla Mudgee Katoomba Port Macquarie Mullumbimby Kempsey Queanbeyan Mungindi Kiama Quirindi Murrurundi Kurri Kurri Raymond Terrace Murwillumbah -

Eurofins | Environment Testing Visitor Information for Brisbane Laboratory

Eurofins | Environment Testing Visitor Information for Brisbane Laboratory Directions ‐ Our lab is located at 1/ 21 Smallwood Place, Murarrie QLD 4172. Once at Borthwick Avenue, take the third exit on the roundabout and turn into Smallwood Place. Our driveway is located at the right hand corner of Smallwood Place. = Eurofins | Environment Testing Parking ‐ Parking spaces are company specific. You can park in any of the free spaces in front of company with Eurofins park sign. If you have any difficulties locating the car park, please call our Business Unit Manager on 07 3902 4606 or Sample Receipt on 07 3902 4611. Eurofins | Environment Testing Brisbane Laboratory T +61 7 3902 4600 Laboratories: 1/21 Smallwood Place Offices : Melbourne Murarrie Adelaide Sydney Queensland 4172 Darwin Brisbane Australia Newcastle Perth ABN: 50 005 085 521 Wollongong QS1061_R2 General Information ‐ Once on site all visitors are to enter through the front office door located to the right and sign-in using our Visitors log book. Office hours are 9am to 5pm Monday-Friday excluding public holidays. ‐ For all deliveries (including sample drop offs) please enter through the roller door located to the left. Drop off hours are from 8am to 6pm Monday-Friday excluding public holidays. ‐ Lastly, our Eurofins | Environment Testing site is a laboratory, so please remember if you are venturing beyond Reception long pants and enclosed shoes must be worn. We are able to provide blue (Visitor) lab coats and safety glasses. We look forward to your visit. Eurofins | Environment Testing Management & Staff Eurofins | Environment Testing Brisbane Laboratory T +61 7 3902 4600 Laboratories: 1/21 Smallwood Place Offices : Melbourne Murarrie Adelaide Sydney Queensland 4172 Darwin Brisbane Australia Newcastle Perth ABN: 50 005 085 521 Wollongong QS1061_R2 . -

Toolijooa Stock List Eastern & Western Sydney August 2009

Eastern Sydney Stock August 2009 Genus species hiko tube Provenance Acacia falcata 150 Pittwater Acacia linifolia 50 Warringah Acacia longifolia 300 Warringah Allocasuarina littoralis 250 Willoughby Allocasurina littoralis 500 Warringah Angophora costata 150 North Sydney Baloskion tetraphyllum 300 Warringah Banksia integrifolia 400 200 Pittwater Banksia integrifolia 200 Warringah Callistemon citrinus 400 300 Manly Callistemon linearis 100 Warringah Casuarina glauca 640 150 Warringah Cerratopetalum apetalum 80 Willoughby Commelina cyanea 20 Warringah Corymbia gummifera 100 Warringah Cymbopogon refractus 80 Pittwater Elaeocarpus reticulatus 20 Warringah Eucalyptus pillularis 300 Willoughby Eucalyptus robusta 20 Warringah Eucalyptus saligna 40 Lane Cove Eucalyptus sieberi 200 Warringah Eucalyptus umbra 100 Warringah Ficus coronata 100 Pittwater Melaleuca armillaris 100 Warringah Melaleuca linearifolia 900 Warringah Melaleuca stypheloides 200 Warringah Microlaena stipoides 120 Lane Cove Pomaderris intermedia 500 Willoughby Trema aspera 300 Pittwater Tristaniopsis laurina 1000 Marrickville Viola hederacae 40 Warringah Xanthorrhoea arborea 100 Mosman Western Sydney Stock August 2009 Genus species hiko tube Provenance Acacia binervia 200 Bankstown Acacia decurrens 400 Parramatta Acacia elongata 600 Bankstown Acacia falcata 1000 Bankstown Acacia floribunda 100 Hornsby Acacia linifolia 360 Cordeaux Acacia longifolia 200 150 Bankstown Acacia mearnsii 400 Cordeaux Acacia rubida 300 Cordeaux Acacia stricta 600 Hornsby Allocasurina littoralis 2000 -

A Brief History of the Mount Keira Tramline

84 NOV /DEC 2000 lllawarra Historical Society Inc. A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE MOUNT KEIRA TRAMLINE 1839 The Rev W B Clarke, who was a qualified geologist, recorded a finding of coal at Mount Keira. 1848 James Shoobert, a retired sea captain and land-owner, drove a tunnel in what is now known as the No. 3 seam. He then observed an outcrop of the No. 2 (4-ft) seam about 21 metres above it, in which the coal was of better quality. 1849 Shoobert then opened a tunnel in the 4-ft seam, which seems to have been on the north side of Para Creek. A track was then cut through the bush to the Mount Keira Road where a depot was established about 400 metres west of the crossroads forming the junction with the main south road. The track and the crossroads both appear on Plan A (page 85), an 1855 proposal to supply Wollongong with water. The first load of coal was taken from this depot to Wollongong Harbour, with much fanfare, on August 27. The coal was delivered from the mine to the depot by bullock drays and dumped there. It was then loaded onto horse-drawn drays and taken to the harbour, where it was bagged and carried on board the waiting vessel, the paddle steamer William the Fourth, and tipped into its hold. [Sydney Morning Herald 10.09.1849) Plan B (page 87) is a line diagram showing the position ofShoobert's road in relation to later developments. 1850 A second tunnel was opened in the 4-ft seam. -

Tourism Opportunities Plan Report Prepared for Kiama Municipal Council July 2018

Tourism Opportunities Plan Report Prepared for Kiama Municipal Council July 2018 1 Kiama Tourism Opportunities Plan – Report Table of Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................... 10 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................ 12 Product and Market Review ....................................................................................................................... 14 Tourism Market Review ............................................................................................................................. 15 Product and Experience Review ............................................................................................................. 17 Defining Kiama’s Hero Experiences ....................................................................................................... 19 Hero Experiences....................................................................................................................................... 20 Tourism Development and Investment Opportunities ..................................................................... 23 Long List of Development Opportunities ................................................................................................. 24 Project Prioritisation ......................................................................................................................................