Seymour Fox and Israel Scheffler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy in Education: Questioning and Dialogue in Schools by Jana Mohr Lone and Michael D

Philosophical Inquiry in Education, Volume 26 (2019), No. 1, pp. 102-105 Review of Philosophy in Education: Questioning and Dialogue in Schools by Jana Mohr Lone and Michael D. Burroughs. New York: Rowman and Littlefield, 2016 TREVOR NORRIS Brock University For several decades philosophers and educational theorists have advocated for the inclusion of philosophy into the K-12 school system instead of reserving it for the post-secondary context. Lone and Burroughs’ Philosophy in Education: Questioning and Dialogue in Schools avoids extensive philosophical considerations about the nature of philosophy or philosophical education, though much emerges implicitly through the activities they present. Instead, it is more of a practical handbook, guidebook, or reference. While Lone and Burroughs outline dozens of simple and effective ways to engage students of younger ages in philosophy, the book is more than just a “how to”: the authors present several compelling arguments that can be used to persuade students, parents, administrators and the general public that philosophy is worthwhile for those of younger ages. Recent years have seen a boom in literature arguing that philosophy in schools is both possible and worthwhile. Even the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy now has an entry for philosophy for children.1 Early founders of P4C include Matthew Lipman and Gareth Matthews, who helped its establishment in the northeastern US in the 1960s and 70s. Examples of recent scholarship include Philosophy in Schools: An Introduction for Philosophers and Teachers by Goering, Shudak, & Wartenberg (2013) which is divided into distinctive approaches for elementary and secondary contexts. Its editors provide a convincing and thorough description of the merits of including philosophy in schools. -

International Centre for Philosophy, Education and Citizenship

International Center for Philosophy, Education and Citizenship PlayWise Olympiads George Ghanotakis, Ph.D. and Pleen le Jeune, University of Sherbrooke student (M.A) «Philosophy thrives on the understanding of, respect and consideration for the diversity of opinions, thoughts and cultures that enrich the way we live in the world. As with tolerance, philosophy is an art of living together, with due regard to rights and common values. It is the ability to see the world with a critical eye, aware of the viewpoints of others, strengthened by the freedom of thought, conscience and belief». Irina Bokova. UNESCO Director-General Extract, World Philosophy Day 2016 Critical acclaim of the game (PlayWise) “An excellent tool in the form of a parlour game. Satisfying for the stimulation and the chance to appreciate each individual’s unique way of seeing things.” – CM Reviewing Journal of Canadian Materials for Youth vol 7/3 Canadian Library Association. “... adapts itself to all ages: it is fun to play for children, interests teens and stimulates adults ...contributes to the development of basic skills in language arts, mathematics, science, and social studies.” - Vie Pédagogique, Quebec Ministry of Education. “ The built in debating aspects of the game provided fun to all players, be they students or adults. Would no doubt enlarge the students understanding of self and others in various life situations, teach students to be analytical and evaluative in judgment making, decision making and problem solving in the learning process. These evaluators all made strong recommendations for their institutions to purchase the game” Professor Louis K.Ho Librarian, Fellow Canadian College of Teachers “ ..has been assessed by the English and French Consultants. -

Philosophy of Education and the Growing Impact of Empirical Research*)

1 Jürgen Oelkers *) Philosophy of Education and the Growing Impact of Empirical Research 1. Point of Departure: The Triumphant Success of Empiricism Empirical research methods have been used in education since the end of the 19th century. Initially experimental methods taken from psychological laboratories of the time were used and quickly also complemented with applied statistics methods which were popularized in American educational science first and foremost by Edward Thorndike. These procedures made it possible to study large test series of students who before had been outside the horizon of education. Field observations were also developed, making it possible to study concrete phenomena in children's play or in adolescents' behavior. The pioneer of this current of research was the psychologist G. Stanley Hall. This international research had undisputed advantages and was also supported politically or by teacher unions. Indeed, demands of the public or relevant groups of stakeholders influenced the behavior of educational science. This in turn brought with it another advantage: Philosophical abstractions had to be avoided as did classification into opposing philosophical camps or approaches. Theoretically speaking, there are no "isms" in empirical research which did not require long-term devotees, but rather merely topics and methods. The topics are practice-oriented and the methods are just as transparent as they are demanding, requiring instruction and constant training. Findings of early empirical research also seemed to actually have an immediate benefit. The famous learning curve from memory research gained admission to the classroom as did the intelligence test and achievement measurements and also contemporary management methods designed to ensure an efficient school organization. -

Forging a Philosophical Foundation for Outcomes-Based Education

International Journal of Education and Research Vol. 2 No. 6 June 2014 Forging a philosophical foundation for Outcomes-Based Education Elias M. Sampa, Ed.D, Arellano University, Manila, Philippines [email protected] / 0998-9740380 ABSTRACT This paper is divided into two main parts. Part one is a discussion on the distinctive character of outcomes- based education (OBE) using the Aristotelian philosophical lens. The second part deals with philosophical themes of knowledge paradigm, ontological, epistemological and pedagogical assumptions and tries to locate them in OBE where they are embedded. Keywords: Outcomes-based education, philosophy, education, Philippines 517 ISSN: 2201-6333 (Print) ISSN: 2201-6740 (Online) www.ijern.com 1. OUTCOMES-BASED EDUCATION (OBE) Philosophy has long been one of the critical foundations in the conception of education. The very notion of ‘outcomes-based’ orients us to a preoccupation with the primacy of the Aristotelian final cause or telos,the purpose or end of education. Taking a cue from this Aristotelian theory one may easily argue: Is education not outcome-based by nature? Isn’t that all education institutions and programs have goals that guide their work? Is it not that in planning curriculums or planning lessons for their classes, educators start by clarifying the purposes and objectives? Yet, our overall education practice and ethos will have alternative evidence to argue from: Isn’t it true that in schools all curriculum and lesson plans are time-based and bound? Is it not that while professors and teachers want students to learn something, they allocate a certain amount of time to study of that topic and then move on, whether or not students have mastered it? How much does the purpose or end matter? More and more it seems the discourse is between ‘coverage’ and ‘uncovering’ or put simply ‘content’ verses ‘outcomes’. -

Confucianism: How Analects Promoted Patriarchy and Influenced the Subordination of Women in East Asia

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2017 Apr 20th, 9:00 AM - 10:15 AM Confucianism: How Analects Promoted Patriarchy and Influenced the Subordination of Women in East Asia Lauren J. Littlejohn Grant High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the Asian History Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, and the Women's History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Littlejohn, Lauren J., "Confucianism: How Analects Promoted Patriarchy and Influenced the Subordination of Women in East Asia" (2017). Young Historians Conference. 9. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2017/oralpres/9 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Confucianism: How Analects Promoted Patriarchy and Influenced the Subordination of Women in East Asia Lauren Littlejohn History 105 Gavitte Littlejohn 1 Introduction Primary sources provide historians insight into how people used to live and are vital to understanding the past. Primary sources are sources of information-artifacts, books, art, and more- that were created close to the time period they are about and by someone who lived in proximity to that period. Primary sources can be first hand accounts, original data, or direct knowledge and their contents are analyzed by historians to draw conclusions about the past. There are many fields where scholars use different forms of primary sources; for example, archaeologists study artifacts while philologists study language. -

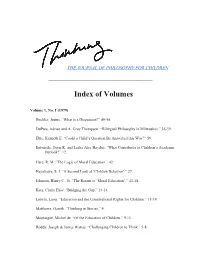

Index of Thinking Volumes

THE JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY FOR CHILDREN __________________________________________________ Index of Volumes Volume 1, No. 1 (1979) Buchler, Justus. “What is a Discussion?” 4954. DuPuis, Adrian and A. Gray Thompson. “Bilingual Philosophy in Milwaukee.” 3539. Eble, Kenneth E. “Could a Child’s Question Be Answered this Way?” 59. Entwistle, Doris R. and Leslie Alec Hayduc. “What Contributes to Children’s Academic Outlook?” 12. Hare, R. M. “The Logic of Moral Education.” 42. Hayakawa, S. I. “A Second Look at ‘Childish Behavior’.” 27. Johnson, Henry C., Jr. “The Return to ‘Moral Education’.” 4148. Katz, Claire Elise. “Bridging the Gap,” 1314. Letwin, Leon. “Education and the Constitutional Rights for Children.” 1119. Matthews, Gareth. “Thinking in Stories.” 4. Montaigne, Michel de. “Of the Education of Children.” 911. Roddy, Joseph & James Watras. “Challenging Children to Think.” 58. Simon, Charlann. “Philosophy for Students with Learning Disabilities.” 2133. Wagner, Paul A.“Philosophy, Children, and ‘Doing Science’.” 5557. Worsfold, Victor L. “What Claims Can Children Make?” 13. Volume 1, No. 2 (1979) Aman, Kenneth and Sister Anna Maria Hartman. “Philosophy for Children in a SpanishSpeaking Contest.” 410. Barr, Donald. “How Important are Categories for Children.” 11. Berman, Ronald. “On Writing Good.” 12. Brent, Frances. “Philosophy and the MiddleSchool Student.” 39. Chesternon, Gilbert Keith. “The Ethics of Elfland.” 1320. Dostoevsky, Fedor. “Ghost and Eternity.” 27. Education Commission of the States. “The Higher Level Skills: Tomorrow’s ‘Basics’.” 11. Freire, Paulo. “Education Through Dialogue.” 11. Gosse, Edmund. “Untitled from Father and Son.” 4346. Hullfish, H. Gordon. “Thinking and Meaning.” 12. -

Documenting the Influence of Noddings's Theory of Care in Moral

Documenting the Influence of Noddings’s Theory of Care in Moral Education and Philosophy of Education: 2003-2013 By © 2017 Gözde Eken M. Ed., Rutgers University, 2012 B. Ed., Gazi University Kastamonu School of Education, 2007 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Educational Leadership and Policy Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chair: Suzanne Rice, PhD. Committee Member: John L. Rury, PhD. Committee Member: Jennifer C. Ng, PhD. Committee Member: Argun Saatçioğlu, PhD. Committee Member: Philip McKnight, PhD. Date Defended: September 27, 2017 ii The dissertation committee for Gozde Eken certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Documenting the Influence of Noddings’s Theory of Care in Moral Education and Philosophy of Education: 2003-2013 Chair: Suzanne Rice, PhD Date Approved: November 17, 2017 iii Abstract Educational research has a broad scope of interest; and, since Ancient Greece, it has constantly interacted with other fields such as ethics, social work, and psychology. For centuries, scholars and researchers have struggled to answer the questions: What is moral knowledge? How do we acquire moral knowledge? What does education mean? The need to answer these questions has motivated educational theorists and philosophers to construct new and thought-provoking educational theories. Many educational theorists and philosophers have improved and/or challenged the theories of interest over time, but few have constructed their own theories. Nel Noddings, a well-respected educational philosopher and a moral theorist, has provided comprehensive answers to these questions through the Theory of Care she constructed. -

Towards the Islamisation of Critical Pedagogy: a Malaysian Case Study

Towards the Islamisation of Critical Pedagogy: A Malaysian Case Study Suhailah Hussien Volume I A Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. The University of Sheffield Department of Educational Studies July 2006 ABSTRACT The starting point for this thesis is the crisis in Muslim education in Malaysia and the response to the crisis suggested by the 'Islamisation of Knowledge' project. It seeks to contribute to this project by analysing its epistemological and methodological problems. On the basis of this analysis, the thesis seeks to ascertain whether an Islamised critical pedagogy can offer a more adequate resolution to the 'crisis'. In order to achieve this, the thesis is divided into two parts. The first part examines the history, causes and effects of the 'crisis' and highlights the effort of some Muslim scholars to resolve it through the Islamisation of Knowledge (10K) project. It then explores whether western critical pedagogy can contribute to the resolution of the 'crisis' by evaluating whether western critical pedagogy can be reconstructed from an Islamic perspective. In doing this, the thesis critically analyses the Islamic philosophy of education and redefines its core educational concepts. Then it provides an ideology-critique of the curriculum and pedagogy of the national education system generally, and Islamic education in Malaysia specifically. From these critiques, the thesis suggests a critical view of curriculum and pedagogy for Islamic education in Malaysia that could assist in achieving its aims. The second part of the thesis tries to assess whether this reconstructed critical pedagogy can be practised in the Malaysian classroom in order to achieve the ideals and values of Islamic education. -

Josef Pieper's Vita Contemplativa As Pedagogical Ground

Philosophy Study, ISSN 2159-5313 August 2014, Vol. 4, No. 8, 537-545. doi: 10.17265/2159-5313/2014.08.002 D DAVID PUBLISHING Virtue Education: Josef Pieper’s Vita Contemplativa as Pedagogical Ground Annette M. Holba Plymouth State University Virtue education in the United States has lost its clout while the corporatization of higher education may be at its peak. The focus of traditional education has shifted from ideas, wisdom, and the love of learning to having a corporate mindset on progress and skills-based knowledge. In many cases, the focus of attention is on remaining viable/sustainable in times of economic decline rather than learning itself, so the resources supporting institutions of higher education are directed into marketing and public relations practices instead of the infrastructure for thinking and learning. This essay draws together three coordinates to make a case for a return to virtue education in the United States. First, the current condition of higher education is shown to have dubiously strayed from a virtue model. Second, the re-emergence of philosophy as a preferred major and its growth in the academy suggest that people realize that something has to change in higher education as they revert back to a broad liberal arts emphasis. Third, a discussion of virtue education from the lens of Josef Pieper’s virtue philosophy, grounded in the Vita Contemplativa, offers renewed possibility to reengaged higher education for a sustainable future. Together, I suggest that the tradition of higher education in the United States is no longer viable and return to a virtue education model is an alternative that might make higher education sustainable. -

Badr Al-Dīn Ibn Jamāʿah and the Highest Good of Islamic Education

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2016 Badr al-Dīn Ibn Jamāʿah and the Highest Good of Islamic Education Omar Qureshi Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons Recommended Citation Qureshi, Omar, "Badr al-Dīn Ibn Jamāʿah and the Highest Good of Islamic Education" (2016). Dissertations. 2293. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/2293 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2016 Omar Qureshi LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO BADR AL-DĪN IBN JAMĀʿAH AND THE HIGHEST GOOD OF ISLAMIC EDUCATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN CULTURAL AND EDUCATIONAL POLICY BY OMAR QURESHI CHICAGO, IL DECEMBER 2016 Copyright by Omar Qureshi, 2016 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would not have been completed were it not for God’s grace and mercy. All praises and gratitude are due to God. Furthermore, it could not have been completed without the great support that I have received from so many people over the years. I wish to offer my most heartfelt thanks to the following people. To my father, Muhammad Anwar Qureshi. I dedicate this work to you. -

Metaphysical Problems and Education

Volume II, Issue VIII, December 2014 - ISSN 2321-7065 Metaphysical Problems and Education Chaman Lal Banga Assistant Professor (Education) Department of Education, ICDEOL, Himachal Pradesh University Shimla India Abstract Philosophy and education are two interrelated disciplines. This is because both centre on man and development. Education makes use of philosophy both as a foundation and the culmination of imparting knowledge and values for human development. It is concerned with explaining the fundamental nature of being and the world. Metaphysics is the study of the nature of things. Metaphysicians ask what kinds of things exist, and what they are like. They reason about such things as whether or not people have free will, in what sense abstract objects can be said to exist, and how it is that brains are able to generate minds. Metaphysics as a speculative branch of philosophy was examined to be a foundation for education. Concepts such as “Matter”, “Mind, “Body”, “Soul, “Reality” among others remain metaphysical issues in education that need to be re-visited for new perspectives to educational thought. Metaphysics prepares the philosopher of education to examine philosophic questions to the extent to which they bear on education issues. Metaphysics as a branch of philosophy involves a speculative way of thinking about world realities to imprint on oneself some transcendental principles that constitute their foundations. Aristotle developed the study of metaphysics to be studied after physics. While physics studies the law of external form of existence, metaphysics thinks over the real essence of things. Its main problems are: What is the nature of existence? What is reality? What is truth? What are its different forms? Is the world one or many? What is space? What is fact? What is casualty? What is change? Is there is God? Has the world progressed? etc. -

Essentialism in Aristotle Author(S): S

Essentialism in Aristotle Author(s): S. Marc Cohen Source: The Review of Metaphysics, Vol. 31, No. 3 (Mar., 1978), pp. 387-405 Published by: Philosophy Education Society Inc. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20127077 Accessed: 23/08/2009 19:33 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=pes. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Philosophy Education Society Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Review of Metaphysics. http://www.jstor.org ESSENTIALISM INARISTOTLE S. MARC COHEN JljSSENTIALISM, as Quine characterizes it, is "the doctrine that some of the attributes of a thing (quite independently of the language inwhich the thing is referred to, if at all) may be essential to the thing, and others accidental."1 In Quine's more austere formal character ization, essentialism is committed to the truth of sentences of the form (A) (3x) (nee Fx .