The Marrow Controversy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction

MJT 10 (1999) 239-257 THE MARROW CONTROVERSY: A DEFENSE OF GRACE AND THE FREE OFFER OF THE GOSPEL by Joseph H. Hall Introduction THE PRISTINE ORTHODOXY of the Scottish Reformation had begun to wane by 1700. This was due in part to the residual influence of the Englishman Richard Baxter’s theology. Baxter (1615-1691), an Amyraldian, conceived of Christ’s death as a work of universal redemption, penal and vicarious but not strictly speaking substitutionary. For Baxter, God offers grace to sinners by introducing the “new law” of repentance and faith. Consequently when penitent sinners “obey” this new law, they obtain a personal saving righteousness. Effectual calling induces such obedience and preserving grace sustains it. This doctrine, known as “Neonomianism,” reflected Amyraldian teaching, with Arminian “new law” teaching as an addendum. The legalistic dimensions of Baxter’s Amyraldianism, along with the increasing influence of Laudian hierarchism,1 brought on 1William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury under Charles I of England, imposed on England, and sought to impose on Scotland, high church Anglicanism during the 1630s. The Scots fiercely and successfully resisted English uniformitarianism under Charles I only to have it re-imposed upon them after the restoration of Charles II. 240 • MID-AMERICA JOURNAL OF THEOLOGY by the Act of Union of 1707,2 made England dominant in both Church and State in Scotland. Added to this was the reintroduction of the abuses of patronage into the Scottish Kirk.3 These factors all contributed to the waning of vigorous, well- balanced Calvinism wherein the warmth of Scotland’s earlier Calvinism, with all its biblical and ecclesiastical integrity, gave way increasingly to doctrinal and spiritual indifference or “moderatism.” Hence those called moderates were those who opposed Reformation doctrine. -

E Marrow Controversy and Seceder Tradition REFORMED H ISTORICAL -THEOLOGICAL S TUDIES

e Marrow Controversy and Seceder Tradition REFORMED H ISTORICAL -THEOLOGICAL S TUDIES General Editors Joel R. Beeke and Jay T. Collier BOOKS IN SERIES : e Christology of John Owen Richard W. Daniels e Covenant eology of Caspar Olevianus Lyle D. Bierma John Diodati’s Doctrine of Holy Scripture Andrea Ferrari Caspar Olevian and the Substance of the Covenant R. Scott Clark Introduction to Reformed Scholasticism Willem J. van Asselt, et al. e Spiritual Brotherhood Paul R. Schaefer Jr. Teaching Predestination David H. Kranendonk e Marrow Controversy and Seceder Tradition William VanDoodewaard e Marrow Controversy and Seceder Tradition Marrow eology in the Associate Presbytery and Associate Synod Secession Churches of Scotland (1733–1799) William VanDoodewaard Reformation Heritage Books Grand Rapids, Michigan e Marrow Controversy and Seceder Tradition © 2011 by William VanDoodewaard All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Direct your requests to the publisher at the following addresses: Reformation Heritage Books 2965 Leonard St. NE Grand Rapids, MI 49525 616-977-0889 / Fax 616-285-3246 [email protected] www.heritagebooks.org Printed in the United States of America 11 12 13 14 15 16/10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 [CIP data] For additional Reformed literature, both new and used, request a free book list from Reformation Heritage Books at the above address. Table of Contents Acknowledgments . vii Introduction ...................................... 1 Part 1: Views of the Gospel and Its Proclamation: e Era of the Marrow Controversy 1. -

Marrow of Modern Divinity.Indd

MMarrowarrow ooff MModernodern DDivinity.inddivinity.indd 1 229/07/20099/07/2009 16:38:5816:38:58 “Anyone who comes to grips with the issues raised in Th e Marrow of Modern Divinity will almost certainly grow by leaps and bounds in understanding three things: the grace of God, the Christian life, and the very nature of the gospel itself. I personally owe it a huge debt. Despite their mild-mannered appearance, these pages contain a powerful piece of propaganda. Read them with great care!” Sinclair B. Ferguson, Senior Minister, Th e First Presbyterian Church, Columbia, South Carolina “Th e Marrow of Modern Divinity is one of the most important text’s of all time” Derek W. H. Th omas, John Richards Professor of Practical and Systematic Th eology, Reformed Th eological Seminary, Jackson, Mississippi MMarrowarrow ooff MModernodern DDivinity.inddivinity.indd 2 229/07/20099/07/2009 16:39:3116:39:31 Copyright © Christian Focus Publications 2009 ISBN 978-1-84550-479-3 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Published in 2009 in the Christian Heritage Imprint by Christian Focus Publications, Geanies House, Fearn, Tain, Ross-shire, IV20 1TW, Scotland, UK www.christianfocus.com Cover design by Paul Lewis Printed in the USA All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior per-mission of the publisher or a licence permitting restricted copying. In the U.K. such licences are issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saff ron House, 6-10 Kirby Street, London, EC1 8TS www.cla.co.uk. -

John Bunyan in the Kilt: the Influence of Bunyan Texts on Religious Expression and Experience in the Scottish Highlands and Islands DONALD E

John Bunyan in the Kilt: The Influence of Bunyan Texts on Religious Expression and Experience in the Scottish Highlands and Islands DONALD E. MEEK ABSTRACT No abstract. Volume 37, pp 155-163 | ISSN 2052-3629 | http://journals.ed.ac.uk/ScottishStudies DOI: 10.2218/ss.v37i0.1805 http://dx.doi.org/10.2218/ss.37i0.1805 John Bunyan in the Kilt: The Influence of Bunyan Texts on Religious Expression and Experience in the Scottish Highlands and Islands DONALD E. MEEK Dr John MacInnes has contributed greatly to our understanding of many different aspects of Highland and Gaelic culture, including evangelical Protestantism and its impact on Gaelic secular tradition. He has also had much to say about translation, commonly from Gaelic to English, and most frequently in the context of insightful reviews of modern Gaelic verse. In appreciation of John’s warm-hearted sharing of insights into both subjects, from which I have benefited immensely, I am delighted to offer him in return a beannachadh which combines both the Christian faith and also translation, though, on this occasion, from English to Gaelic. As John is well aware, evangelical Protestantism in its Highland garb was deeply indebted to seventeenth-century English Puritan writers such as Richard Baxter (1615–1691) of Kidderminster, whose Call to the Unconverted was translated into Gaelic in 1750, thus establishing a literary genre which has continued, though in diminishing form, well into the twentieth century. In particular, I wish to consider the writings of John Bunyan (1628–1688) of Bedford, whose work is well known in the British Isles, and has been translated into many languages, including Gaelic (Sharrock 1968; Dunan-Page 2010). -

History of Scotland: Vol

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-60034-8 - History of Scotland: Vol. III.: From the Revolution of 1689 to the Disruption, 1843 P. Hume Brown Frontmatter More information (!!ambtibge ~istotical ~eties EDITED BY G. W. PROTHERO, LITT.D. HONORARY FELLOW OF KING'S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE. HISTORY OF SCOTLAND VOLUME III © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-60034-8 - History of Scotland: Vol. III.: From the Revolution of 1689 to the Disruption, 1843 P. Hume Brown Frontmatter More information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-60034-8 - History of Scotland: Vol. III.: From the Revolution of 1689 to the Disruption, 1843 P. Hume Brown Frontmatter More information HISTORY OF SCOTLAND VOL. III. FROM THE REVOLUTION OF 1689 TO THE DISRUPTION, 1843 BV P. HUME BROWN, M.A., LL.D., HISTORIOGRAPHER-ROYAL FOR SCOTLAND, AND FRASER PROFESSOR OF ANCIENT (SCOTTISH) HISTORY AND PAI.AEOGRAPHY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH. CAMBRIDGE: AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS 19II © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-60034-8 - History of Scotland: Vol. III.: From the Revolution of 1689 to the Disruption, 1843 P. Hume Brown Frontmatter More information CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao Paulo, Delhi, Tokyo, Mexico City Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of -

Spontaneous Article Science, Metaphysics and Calvinism: the God of James Croll Diarmid A

Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh,1–9, 2021 Spontaneous Article Science, metaphysics and Calvinism: the God of James Croll Diarmid A. FINNEGAN* Geography, School of Natural and Built Environment, Queen’s University Belfast, Northern Ireland, BT7 1NN. *Corresponding author. Email: d.fi[email protected] ABSTRACT: Science, for James Croll, began and ended in metaphysics. Metaphysics, in turn, pro- vided proof of a First and Final Cause of all things. This proof rested on two metaphysical principles: that every event must have a cause, and that the determination of a cause is distinct from its production. This argument emerged from his deeply held religious commitments. As a 17-year-old, he converted to a Calvinist and evangelical form of Christianity. After a period of questioning the Calvinist system, he embraced it again through reading the famous treatise on the will by the New England theologian, Jona- than Edwards. This determinedly metaphysical work, which engaged as much with Enlightenment thought as with Calvinism, defended the view that the will was not a self-determining cause of human action. This ‘hard case’ provided the basis for a larger claim that every act whatever has a cause, and that the production of an act was different from its determination. In part through reading Edwards, Croll remained a devout and convinced ‘moderate’ Calvinist for the rest of his life. He also developed a deep love of metaphysics and became convinced that without it, everything, including sci- ence, remained confused and in darkness. For Croll, even the most basic science could not be properly conducted without prior metaphysical principles. -

Theology of Assurance Within the Marrow Controversy

THEOLOGY OF ASSURANCE WITHIN THE MARROW CONTROVERSY by Gerald L. Chrisco M.A.R., Reformed Theological Seminary, 2009 A THESIS Submitted to the faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Religion at Reformed Theological Seminary Charlotte, North Carolina January 2009 ii Copyright © 2008 by Gerald L. Chrisco All rights reserved ABSTRACT Theology of Assurance Within the Marrow Controversy Gerald L. Chrisco While the source of struggle may differ from one Christian believer’s experience to another’s, many speak of the presence of doubt and its effect. Pastorally, assurance is a key doctrine for the edification of the body of Christ. Theologically, the topic has been hotly debated across many eras of church history. The 18th Century Marrow Controversy is one such debate that provides an interesting and structured platform from which the doctrine can be examined. This thesis begins the examination with the following proposition: Although their soteriology in general was condemned by the 1722 General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, the Marrow Brethren’s dichotomy of the “assurance of sense” and the “assurance of faith” substantially reconciled their assertion that “assurance is the essence of saving faith” to relevant sections of the Westminster Confession and the teachings of John Calvin. Utilizing as much primary source material as possible, evidence is presented to show how the words of the Marrow Brethren are compatible with those of Calvin and the major Reformation confessions, particularly Westminster. While their emphases may differ, each of these three viewpoints includes a common dichotomy: the ever present absolute assurance of the truth of the promises of God which is inherent in saving faith and the subjective experiential assurance of a believer which can be shaken by doubt. -

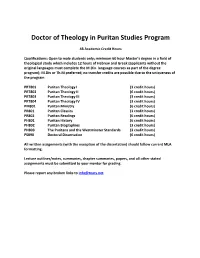

Doctor of Theology in Puritan Studies Program

Doctor of Theology in Puritan Studies Program 48 Academic Credit Hours Qualifications: Open to male students only; minimum 60 hour Master’s degree in a field of theological study which includes 12 hours of Hebrew and Greek (applicants without the original languages must complete the M.Div. language courses as part of the degree program); M.Div or Th.M preferred; no transfer credits are possible due to the uniqueness of the program. PRT801 Puritan Theology I (3 credit hours) PRT802 Puritan Theology II (6 credit hours) PRT803 Puritan Theology III (3 credit hours) PRT804 Puritan Theology IV (3 credit hours) PM801 Puritan Ministry (6 credit hours) PR801 Puritan Classics (3 credit hours) PR802 Puritan Readings (6 credit hours) PH801 Puritan History (6 credit hours) PH802 Puritan Biographies (3 credit hours) PH803 The Puritans and the Westminster Standards (3 credit hours) PS890 Doctoral Dissertation (6 credit hours) All written assignments (with the exception of the dissertation) should follow current MLA formatting. Lecture outlines/notes, summaries, chapter summaries, papers, and all other stated assignments must be submitted to your mentor for grading. Please report any broken links to [email protected]. PRT801 PURITAN THEOLOGY I: (3 credit hours) Listen, outline, and take notes on the following lectures: Who were the Puritans? – Dr. Don Kistler [37min] Introduction to the Puritans – Stuart Olyott [59min] Introduction and Overview of the Puritans – Dr. Matthew McMahon [60min] English Puritan Theology: Puritan Identity – Dr. J.I. Packer [79] Lessons from the Puritans – Ian Murray [61min] What I have Learned from the Puritans – Mark Dever [75min] John Owen on God – Dr. -

Thomas Boston

Thomas Boston Author(s): Anonymous Publisher: Description: This very concise article briefly details the life, ministry, and writings of the 18th century Scottish theologian, Thomas Boston. Kathleen O©Bannon CCEL Staff Subjects: Christian Denominations Protestantism Post-Reformation Other Protestant denominations Presbyterianism. Calvinistic Methodism i Contents Life of Thomas Boston 1 ii This PDF file is from the Christian Classics Ethereal Library, www.ccel.org. The mission of the CCEL is to make classic Christian books available to the world. • This book is available in PDF, HTML, ePub, and other formats. See http://www.ccel.org/ccel/anonymous/bostonlife.html. • Discuss this book online at http://www.ccel.org/node/2990. The CCEL makes CDs of classic Christian literature available around the world through the Web and through CDs. We have distributed thousands of such CDs free in developing countries. If you are in a developing country and would like to receive a free CD, please send a request by email to [email protected]. The Christian Classics Ethereal Library is a self supporting non-profit organization at Calvin College. If you wish to give of your time or money to support the CCEL, please visit http://www.ccel.org/give. This PDF file is copyrighted by the Christian Classics Ethereal Library. It may be freely copied for non-commercial purposes as long as it is not modified. All other rights are re- served. Written permission is required for commercial use. iii Life of Thomas Boston Life of Thomas Boston Thomas Boston Born in 1676, in the town of Duns, in the Border country of Scotland, Thomas Boston learned through his childhood experiences to sympathise with the Presbyterian cause. -

TMSJ 5/1 (Spring 1994) 43-71

TMSJ 5/1 (Spring 1994) 43-71 DOES ASSURANCE BELONG TO THE ESSENCE OF FAITH? CALVIN AND THE CALVINISTS Joel R. Beeke1 The contemporary church stands in great need of refocusing on the doctrine of assurance if the desirable fruit of Christian living is to abound. A relevant issue in church history centers in whether or not the Calvinists differed from Calvin himself regarding the relationship between faith and assurance. The difference between the two was quantitative and method- ological, not qualitative or substantial. Calvin himself distinguished between the definition of faith and the reality of faith in the believer's experience. Alexander Comrie, a representative of the Dutch Second Reformation, held essentially the same position as Calvin in mediating between the view that assurance is the fruit of faith and the view that assurance is inseparable from faith. He and some other Calvinists differ from Calvin in holding to a two-tier approach to the consciousness of assurance. So Calvin and the Calvinists furnish the church with a model to follow that is greatly needed today. * * * * * Today many infer that the doctrine of personal assurance`that is, the certainty of one's own salvation`is no longer relevant since nearly all Christians possess assurance in an ample degree. On the contrary, it is probably true that the doctrine of assurance has particular relevance, because today's Christians live in a day of minimal, not maximal, assurance. Scripture, the Reformers, and post-Reformation men repeatedly 1Joel R. Beeke, PhD, is the Pastor of the First Netherlands Reformed Congregation, Grand Rapids, Michigan, and Theological Instructor for the Netherlands Reformed Theological School. -

THE MARROW CONTROVERSY #01: HISTORICAL DETAILS the Marrow Controversy by Dr

THE MARROW CONTROVERSY #01: HISTORICAL DETAILS The Marrow Controversy By Dr. Sinclair B. Ferguson Preached on: Monday, February 2, 2004 Greenville Seminary & Mt. Olive 200 E. Main St Taylors, SC 29687 Website: www.gpts.edu Online Sermons: www.sermonaudio.com/gpts Corrections and annotations by William H. Gross www.onthewing.org January 2014 The subject that has been allotted to me for these three conference addresses is, as you would have noticed from the program, “Pastoral Lessons From the Marrow Controversy.” You may well wonder what the Marrow Controversy is or was. Let me say to you that it is not some strange sect that appeared in Scotland arguing at some time about the price of butcher meat, nor, for that matter, about the true interpretation of 1 Corinthians chapter eight. It is, indeed, as we shall see in these days together, one of the least known and yet one of the most pastorally significant of all the theological controversies that have taken place within the area of reformed theology. Many of you, I know, will have read that famous book The Marrow of Modern Divinity and many of you, perhaps, will know a good deal about the Marrow Controversy. But it may be that there are some of us here today who for one reason or another are not acquainted with the historicity of that controversy. And so what I have planned to do for part of our opening address in this theme is to take you a little into the historical details of the controversy, if you will bear with me. -

Mackenzie, Jonathan Peter

UHI Thesis - pdf download summary Thomas Boston and the doctrine of God’s will MacKenzie, Jonathan Peter DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (AWARDED BY OU/ABERDEEN) Award date: 2011 Awarding institution: The University of Edinburgh Link URL to thesis in UHI Research Database General rights and useage policy Copyright,IP and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the UHI Research Database are retained by the author, users must recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement, or without prior permission from the author. Users may download and print one copy of any thesis from the UHI Research Database for the not-for-profit purpose of private study or research on the condition that: 1) The full text is not changed in any way 2) If citing, a bibliographic link is made to the metadata record on the the UHI Research Database 3) You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain 4) You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the UHI Research Database Take down policy If you believe that any data within this document represents a breach of copyright, confidence or data protection please contact us at [email protected] providing details; we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 05. Oct. 2021 Student Declaration “I, Jonathan Mackenzie, confirm that I composed the thesis, that it has not been accepted in any previous application for a degree, that the work is my own, and that all quotations have been distinguished by quotation marks and the sources of information specifically acknowledged.” Jonathan Mackenzie 1/12/10 1 Acknowledgements With the completion of this thesis I would like to thank a number of people who helped form and shape the final product.