Sierra Leone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reference Map of Bombali, Northern Province, Sierra Leone

MA002_Bombali, Northern Province Sagalireh ol a Kalia K en or Kurukonko té K Sirekude Bindi Madina K Woula aba Kambia L Folosaba olo Sinkunia Sainya Kamba Dembel Dembelia Reference map - Sink Mamudia s ie of arc le S c GUINEA Litt Bombali, Northern Musaia Mana Yana Wara Province, Wara Tambakha Bafod Sierra Leone Sumata Mongo Bafodia Tambaka Sulima GUINEA a n Benekoro lu u K Kasunko Kabala NORTHERN Sandikoro Wara adi B Maproto Wara Yisimaia Freetown Yagal Sella Kasasi Diri N Madina ' Samaia Limba Dunduko EASTERN 0 3 Sengbe ° Kamakwie 9 Bramaia SOUTHERN Kayungbula Lengekoro Laia Koinadugu o LIBERIA k to Sanda o w a Loko M Kukuna Kamalu Fadugu Settlement Borders o Modia Ka-Linti Basa k o Capital National l Kasobo wo a Kabutcha R M ok City Province Matoto Ka-Soeleh Tonko el Magbaimba Town District Basia Madina Junction Ka-Katula Limba Laiadi Ka-Fanta Gbanti Ndorh village Chiefdom Kongatalla Kamarank Fonaia Diang Kasimbara Gbinle Kafanye Foria Dixing NORTHERN Lungi Kasengenta Physical es Masselleh Kagberi ci r a Kania c Mafafila Yanwulia Lake Coastline S t Biriwa a Darakuru e r Basia Bombali River G Masutu Kumunkalia Kambia Robomp Sanda Kunya Transport Railway Sanda Tendaran Kamabai Alikalia o Kambia Masungbala Rolabie Magbolont Airport Roads Ribie Kalansogoia Makoba Mateboi Pendembu ⛡ Port Primary Sumbuya ole Pintikilie ab M Rolal-Kamathma a Secondary l Gbendembu i h Magbema i Bendugu Kumala Rokantin asu k Ngowa M mu a Tertiary n Libeisaygahun e M Bumbuna Rok-Toloh er Mayaki abol iv Shimbeck Rothain-Thalla M e R Kandeya N ° Keimadugu 9 0 -

ISOLATION CAPACITY December 2016

9 Sierra Leone ISOLATION CAPACITY December 2016 n “n” shows the number of isolation bed IPC Focal Person Standby isolation unit in hospital level Physician/CHO Permanent structure Nurse/Midwife/MCHA Standby isolation unit in hospital level Temporary structure Hygienist/Support Staff/Non-clinical staff Standby isolation unit in PHU level Permanent structure Piped water Standby isolation unit in PHU level Temporary structure Bucket with faucet Active Isolation Unit in hospital Level Pipe born water Borehole Active Isolation Unit in PHU Level Incinerator Under construction isolation unit Isolation unit is not equipped yet Isolation unit is not officially handed over to DHMT yet Incinerator is out of order GREEN Over 80% IPC compliance Burn pit AMBER Between 60% – 79% IPC compliance Incinerator is under construction RED Below 60% IPC compliance Inappropriate waste management Inadequate water supply OVERVIEW Green IPC Amber IPC Red IPC Compliance Compliance Compliance (scored 80 - 100 %) (scored 60 - 79 %) (scored below 60%) # of # of # of # of # of # of Isolation Isolation Isolation Isolation Isolation Isolation DISTRICTS Units Beds Units Beds Units Beds Permanent Structure Permanent Structure Temporary Construction/ Under over handedNot officially NumberBeds Isolationof Bo 11 15 9 13 1 1 1 1 Bombali 25 1 60 9 26 15 32 1 2 Bonthe 2 6 2 6 Kailahun 7 10 7 10 Kambia 1 7 12 1 12 Kenema 5 1 15 6 15 Koinadugu 1 5 4 1 4 Kono 1 1 9 10 2 10 Moyamba 1 7 4 1 4 Port Loko 7 9 22 7 22 Pujehun 9 1 30 9 30 Tonkolili 1 2 6 10 3 10 Western Area 3 1 1 98 4 98 -

G U I N E a Liberia Sierra Leone

The boundaries and names shown and the designations Mamou used on this map do not imply official endorsement or er acceptance by the United Nations. Nig K o L le n o G UINEA t l e a SIERRA Kindia LEONEFaranah Médina Dula Falaba Tabili ba o s a g Dubréka K n ie c o r M Musaia Gberia a c S Fotombu Coyah Bafodia t a e r G Kabala Banian Konta Fandié Kamakwie Koinadugu Bendugu Forécariah li Kukuna Kamalu Fadugu Se Bagbe r Madina e Bambaya g Jct. i ies NORTHERN N arc Sc Kurubonla e Karina tl it Mateboi Alikalia L Yombiro Kambia M Pendembu Bumbuna Batkanu a Bendugu b Rokupr o l e Binkolo M Mange Gbinti e Kortimaw Is. Kayima l Mambolo Makeni i Bendou Bodou Port Loko Magburaka Tefeya Yomadu Lunsar Koidu-Sefadu li Masingbi Koundou e a Lungi Pepel S n Int'l Airport or a Matotoka Yengema R el p ok m Freetown a Njaiama Ferry Masiaka Mile 91 P Njaiama- Wellington a Yele Sewafe Tongo Gandorhun o Hastings Yonibana Tungie M Koindu WESTERN Songo Bradford EAS T E R N AREA Waterloo Mongeri York Rotifunk Falla Bomi Kailahun Buedu a i Panguma Moyamba a Taiama Manowa Giehun Bauya T Boajibu Njala Dambara Pendembu Yawri Bendu Banana Is. Bay Mano Lago Bo Segbwema Daru Shenge Sembehun SOUTHE R N Gerihun Plantain Is. Sieromco Mokanje Kenema Tikonko Bumpe a Blama Gbangbatok Sew Tokpombu ro Kpetewoma o Sh Koribundu M erb Nitti ro River a o i Turtle Is. o M h Sumbuya a Sherbro I. -

Sierra Leone Unamsil

13o 30' 13o 00' 12o 30' 12o 00' 11o 30' 11o 00' 10o 30' Mamou The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply ger GUINEA official endorsemenNt ior acceptance by the UNAMSIL K L United Nations. o l o e l n a Deployment as of t e AugustKindia 2005 Faranah o o 10 00' Médina 10 00' National capital Dula Provincial capital Tabili s a Falaba ie ab o c K g Dubréka Town, village r n a o c M S Musaia International boundary t Gberia Coyah a Bafodia UNMO TS-11 e Provincial boundary r Fotombu G Kabala Banian Konta Bendugu 9o 30' Fandié Kamakwie Koinadugu 9o 30' Forécariah Kamalu li Kukuna Fadugu Se s ie agbe c B Madina r r a e c SIERRA LEONE g Jct. e S i tl N Bambaya Lit Ribia Karina Alikalia Kurubonla Mateboi HQ UNAMSIL Kambia M Pendembu Yombiro ab Batkanuo Bendugu l e Bumbuna o UNMO TS-1 o UNMO9 00' HQ Rokupr a 9 00' UNMO TS-4 n Mamuka a NIGERIA 19 Gbinti p Binkolo m Kayima KortimawNIGERIA Is. 19 Mange a Mambolo Makeni P RUSSIA Port Baibunda Loko JORDAN Magburaka Bendou Mape Lungi Tefeya UNMO TS-2 Bodou Lol Rogberi Yomadu UNMO TS-5 Lunsar Matotoka Rokel Bridge Masingbi Koundou Lungi Koidu-Sefadu Pepel Yengema li Njaiama- e Freetown M o 8o 30' Masiaka Sewafe Njaiama 8 30' Goderich Wellington a Yonibana Mile 91 Tungie o Magbuntuso Makite Yele Gandorhun M Koindu Hastings Songo Buedu WESTERN Waterloo Mongeri Falla York Bradford UNMO TS-9 AREA Tongo Giehun Kailahun Tolobo ia Boajibu Rotifunk a T GHANA 11 Taiama Panguma Manowa Banana Is. -

9. Ibemenuga and Avoaja

Animal Research International (2014) 11(1): 1905 – 1916 1905 ASSESSMENT OF GROUNDWATER QUALITY IN WELLS WITHIN THE BOMBALI DISTRICT, SIERRA LEONE 1IBEMENUGA, Keziah Nwamaka and 2AVOAJA, Diana Akudo 1Department of Biological Sciences, Fourah Bay College, University of Sierra Leone, Mount Aureol, Freetown, Sierra Leone. 2Department of Zoology and Environmental Biology, Michael Okpara University, Umudike, Abia State, Nigeria. Corresponding Author: Ibemenuga, K. N. Department of Biological Sciences, Anambra State University, Uli, Anambra State, Nigeria. Email: [email protected] Phone: +234 8126421299 ABSTRACT This study assessed the quality of 60 groundwater wells within the Bombali District of Sierra Leone. Water samples from the wells were analysed for physical (temperature, turbidity, conductivity, total dissolved solids and salinity), chemical (pH, nitrate-nitrogen, sulphate, calcium, ammonia, fluoride, aluminium, iron, copper and manganese) parameters using potable water testing kit; and bacteriological (faecal and non-faecal coliforms) qualities. Results show that 73% of the samples had turbidity values below the WHO, ICMR and United USPHS standards of 5 NTU. The electrical conductivity (µµµS/cm) of 5% of the whole samples exceeded the WHO guideline value, 8% of the entire samples had values higher than the WHO, ICMR and USPHS recommended concentration. In terms of iron, 25% of all the samples had values in excess of WHO, ICMR and USPHS recommended value of 0.3mg/l. For manganese, 12% of the entire samples had values more than the WHO and ICMR standards. On the other hand, more water samples (22%) had manganese values above USPHS guideline value. For bacteriological quality, 28% of the wells were polluted by faecal and non-faecal coliforms. -

Continuous Results Monitoring and Support System

Continuous Results Monitoring and Support System Bombali/Sierra Leone First Bimonthly Report September 2016 Continuous Results Monitoring and Support System Report—SIAPS/Sierra Leone, September 2016 This report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the US Agency for International Development (USAID), under the terms of cooperative agreement number AID-OAA-A-11-00021. The contents are the responsibility of Management Sciences for Health and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. About SIAPS The goal of the Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services (SIAPS) Program is to ensure the availability of quality pharmaceutical products and effective pharmaceutical services to achieve desired health outcomes. Toward this end, the SIAPS results areas include improving governance, building capacity for pharmaceutical management and services, addressing information needed for decision-making in the pharmaceutical sector, strengthening financing strategies and mechanisms to improve access to medicines, and increasing quality pharmaceutical services. Recommended Citation This report may be reproduced if credit is given to SIAPS. Please use the following citation. Continuous Results Monitoring and Support System Report Bombali/ Sierra Leone, September 2016. Submitted to the US Agency for International Development by the Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services (SIAPS) Program. Arlington, VA: Management Sciences for Health. Key Words Sierra Leone, Bombali, Continuous Results Monitoring and Support System (CRMS) Report Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services Pharmaceuticals and Health Technologies Group Management Sciences for Health 4301 North Fairfax Drive, Suite 400 Arlington, VA 22203 USA Telephone: 703.524.6575 Fax: 703.524.7898 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.siapsprogram.org ii CONTENTS Acronyms ...................................................................................................................................... -

Sierra Leone

GOVERNMENT OF SIERRA LEONE Survey of Availability of Modern Contraceptives and Essential Life-Saving Maternal and Reproductive Health Medicines in Service Delivery Points in Sierra Leone VOLUME TWO - TABLES Z2p(1 − p) n = d2 Where n = minimal sample size for each domain Z = Z score that corresponds to a confidence interval p = the proportion of the attribute (type of SDP) expressed in decimal d = percent confidence level in decimal February 2011 UNFPA SIERRA LEONE Because everyone counts This is Volume Two of the results of the Survey on the Availability of ModernContraceptives and Essential Life-Saving Maternal and Reproductive Health Medicines in Service Delivery Points in Sierra Leone. It is published by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Country Office in Sierra Leone. It contains all tables generated from collected data, while Volume One (published separately) presents the Analytical Report. Both are intended to fill the critical dearth of reliable, high quality and timely data for programme monitoring and evaluation. Cover Diagram: Use of sampling formula to obtain sample size in Volume One UNFPA SIERRA LEONE Survey of Availability of Modern Contraceptives and Essential Life-Saving Maternal and Reproductive Health Medicines in Service Delivery Points in Sierra Leone VOLUME TWO - TABLES Survey of Availability of Modern Contraceptives and Essential Life-Saving Maternal and Reproductive Health Medicines in Service Delivery Points in Sierra Leone: VOLUME TWO - TABLES 3 UNFPA SIERRA LEONE 4 Survey of Availability of Modern Contraceptives -

Summary of Recovery Requirements (Us$)

National Recovery Strategy Sierra Leone 2002 - 2003 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 4. RESTORATION OF THE ECONOMY 48 INFORMATION SHEET 7 MAPS 8 Agriculture and Food-Security 49 Mining 53 INTRODUCTION 9 Infrastructure 54 Monitoring and Coordination 10 Micro-Finance 57 I. RECOVERY POLICY III. DISTRICT INFORMATION 1. COMPONENTS OF RECOVERY 12 EASTERN REGION 60 Government 12 1. Kailahun 60 Civil Society 12 2. Kenema 63 Economy & Infrastructure 13 3. Kono 66 2. CROSS CUTTING ISSUES 14 NORTHERN REGION 69 HIV/AIDS and Preventive Health 14 4. Bombali 69 Youth 14 5. Kambia 72 Gender 15 6. Koinadugu 75 Environment 16 7. Port Loko 78 8. Tonkolili 81 II. PRIORITY AREAS OF SOUTHERN REGION 84 INTERVENTION 9. Bo 84 10. Bonthe 87 11. Moyamba 90 1. CONSOLIDATION OF STATE AUTHORITY 18 12. Pujehun 93 District Administration 18 District/Local Councils 19 WESTERN AREA 96 Sierra Leone Police 20 Courts 21 Prisons 22 IV. FINANCIAL REQUIREMENTS Native Administration 23 2. REBUILDING COMMUNITIES 25 SUMMARY OF RECOVERY REQUIREMENTS Resettlement of IDPs & Refugees 26 CONSOLIDATION OF STATE AUTHORITY Reintegration of Ex-Combatants 38 REBUILDING COMMUNITIES Health 31 Water and Sanitation 34 PEACE-BUILDING AND HUMAN RIGHTS Education 36 RESTORATION OF THE ECONOMY Child Protection & Social Services 40 Shelter 43 V. ANNEXES 3. PEACE-BUILDING AND HUMAN RIGHTS 46 GLOSSARY NATIONAL RECOVERY STRATEGY - 3 - EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ▪ Deployment of remaining district officials, EXECUTIVE SUMMARY including representatives of line ministries to all With Sierra Leone’s destructive eleven-year conflict districts (by March). formally declared over in January 2002, the country is ▪ Elections of District Councils completed and at last beginning the task of reconstruction, elected District Councils established (by June). -

Northern Province

SIERRA LEONE NORTHERN PROVINCE Chiefdom Geo Codes Geo Code Name Bombali 45 Bombali Shebora 46 Makari Gbanti 47 Paki Masabong Banguraya 48 Leibasgayahun Kamagbungban I ! ! Bantahun Dembelia Sinkunia ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Kafaren ! ! P!etewoh ! Soriya ! ! Kidoia ! 49 Sanda Tendaren ! Kaso! ria ! !! ! Alagiya !! !! Upk!osay Kor!os ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Dogoto ! !! ! ! K!um! a! i ! ! Purikoh ! Sabuya ! !! Kaliere ! ! Wambaya ! ! ! Gib!iya ! ! ! ! Kanaya 50 Magbaiamba Ngowahua K! abetor Kasongo Ganya ! ! ! N'J!ura ! ! ! ! ! ! Bo! ntola ! ! Fre! nken ! )"! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Gbankan Ferenya ! ! Taelia ! ! ! ! ! Makaia ! !! Sungbaya ! Karibum ! ! 51 Gbanti Kamaranka Kabruma Dufe Yonkaya Dare-Salam ! ! ! ! Tanduia ! ! ! ! Kabaia Gobu Defe Kambitambaia ! ! Dansaia Kagbokoso ! ! Kalia ! ! ! ! !! ! Yolaia !! ! 52 Sanda Loko ! ! Sankan ! ! ! ! Ganya! Ganya Mak!aya Kamadolay ! Y! enke ! ! ! !! Karifaya !! ! K! akan!ara Selie I ! ! Cawuya ! ! Was!sa I !! Soy! a ! 53 Sella Limba ! ! ! ! ! !! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! !!!! ! ! Nimebadi ! Sere Kude !! Koffin !!!! Gulusaya ! ! ! ! Kolon ! ! Modia ! Kawulia ! ! ! ! Bindiya ! ! 54 Tambakka ! ! Morikalia ! ! ! ! ! Gbind!i I ! Kobalia ! Wassa ! Yawuya ! Nyakasa ! ! ! Kak!opra ! ! ! Kamanday ! ! ! ! ! Duraia ! Salifuia ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! Sobila 55 Gbendembu Ngowahun Ko!tti ! Fosia ! ! ! ! M! omi ! 5 Kasella ! Gor!eh Lakatha Malanga Yanga I Kumiya ! Kodandain ! !! ! s Yenkisa I Nu!m!uma I Kimbilie Kambaidi 56 Safroko Limba ! ! ! ! Kunbuluya Tum!aniya! ! ! ! Foyae Dumbaia Dandaia e !! ! -

Sierraleone Local Council Ward Boundary Delimitation Report

NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION Sierra Leone Local Council Ward Boundary Delimitation Report Volume Two Meets and Bounds April 2008 Table of Contents Preface ii A. Eastern region 1. Kailahun District Council 1 2. Kenema City Council 9 3. Kenema District Council 12 4. Koidu/New Sembehun City Council 22 5. Kono District Council 26 B. Northern Region 1. Makeni City Council 34 2. Bombali District Council 37 3. Kambia District Council 45 4. Koinadugu District Council 51 5. Port Loko District Council 57 6. Tonkolili District Council 66 C. Southern Region 1. Bo City Council 72 2. Bo District Council 75 3. Bonthe Municipal Council 80 4. Bonthe District Council 82 5. Moyamba District Council 86 6. Pujehun District Council 92 D. Western Region 1. Western Area Rural District Council 97 2. Freetown City Council 105 i Preface This part of the report on Electoral Ward Boundaries Delimitation process is a detailed description of each of the 394 Local Council Wards nationwide, comprising of Chiefdoms, Sections, Streets and other prominent features defining ward boundaries. It is the aspect that deals with the legal framework for the approved wards _____________________________ Dr. Christiana A. M Thorpe Chief Electoral Commissioner and Chair ii CONSTITUTIONAL INSTRUMENT No………………………..of 2008 Published: THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT, 2004 (Act No. 1 of 2004) THE KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL (ESTABLISHMENT OF LOCALITY AND DELIMITATION OF WARDS) Order, 2008 Short title In exercise of the powers conferred upon him by subsection (2) of Section 2 of the Local Government Act, 2004, the President, acting on the recommendation of the Minister of Internal Affairs, Local Government and Rural Development, the Minister of Finance and Economic Development and the National Electoral Commission, hereby makes the following Order:‐ 1. -

Guinea Liberia

Syke Street Connaught Hospital Ola During EPI Dental Hospital Marie Stopes ĝ EPI Hospital ĝ ĝ PCMH Freetown ĝ ĝ King Harman ĝ Kissy Mental Road Hospital ĝ Hospital 10°N ĝ ĝ Dembelia 34 Military ĝ Hospital ĝ Rokupr Govt. 12.8 km Hospital - Sink ĝ Prisons Hospital Lumley Govt. Hospital Gbindi Bindi 7 km 12.2 km Port Loko 2.2 ĝ km Western Sinkunia Falaba 0.7 km Goderich Heart & Hands Emergency Hospital Folosaba Surgical Hospital Area Dembel Sinkunia Falaba ĝ ĝ Mongo Sierra Leone ĝ Friendship 54.5 km Sulima Lakka 6.8 km Hospital Jui Govt Urban 11 km Hospital Gberia Musaia CHC Wara Wara Timbako Bafod Tambakha 55.1 km Dogoloya 27.1 km 9.5 km 47.7 km Fintonia CHC 15.2 km Bafodia Rural Renewable Energy Project Western Little Scarcies Bafodia Area Guinea Karene Rural Koinadugu 3.6 km 26.1 km Kathantha Yagala Kabala Yimboi CHC Koinadugu Wara Wara 2 CHC 7.4 km Bendugu 54 Community Health Centres Sella Limba Yagal 11.1 km 17.3 km Sengbe Mongo Bendugu (! Kasunko 9°30'N Kamakwie Kamakwie Town Falaba Seria (Work package 1) 15.4 km Bramaia 43.2 km Kamasasa CHC Sanda Loko Bumbuna 2 Moyamba Kukuna CHC Kamalo Great Scarcies (! Kondembaia 41.7 km (! Firawa 6.5 km Fadugu 50 Mini Grids (Work Package 1+) 63.6 km Rokel or Seli Tonko Limba Kamaron 44.6 km Kamaranka CHC Magbaimba Madina Madina Ndorh Junction Gbanti Kamarank Diang Bagbe Biriwa 40 Mini Grids (Work Package 2) 38.7 km Kagbere CHC 30.7 km Gbalamuya CHC 7.7 km Kambia Karina 5.6 km Sanda Sanda Kamabai Alikalia Alikalia 5.7 km Magbolont Tendaran 3.2 (! Kalansogoia Nieni km Kambia 23.5 km 8.1 km Neya Gbinle Kambia Masungbala 19.1 km Gbendembu Pendembu Batkanu CHC Bumbuna 1 Yiffin Dixing Baimoi Munu Sendugu CHC Bendugu 78.5 km Wulalu Magbema 34.9 km Bumbuna Town(! Bumbuna Legend 22.9 km 51.5 km 36.7 km 21.7 km (! Rokupr 24.9 km Kamankay Libeisaygahun !. -

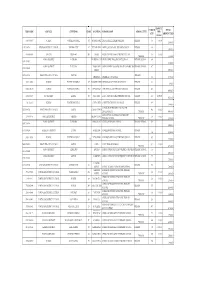

Emis Code Council Chiefdom Ward Location School Name

AMOUNT ENROLM TOTAL EMIS CODE COUNCIL CHIEFDOM WARD LOCATION SCHOOL NAME SCHOOL LEVEL PER ENT AMOUNT PAID CHILD 5103-2-09037 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 391 ROGBANGBA ABDUL JALIL ACADEMY PRIMARY PRIMARY 369 10,000 3,690,000 1291-2-00714 KENEMA DISTRICT COUNCIL KENEMA CITY 67 FULAWAHUN ABDUL JALIL ISLAMIC PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 380 3,800,000 4114-2-06856 BO CITY TIKONKO 289 SAMIE ABDUL TAWAB HAIKAL PRIMARY SCHOOL 610 10,000 PRIMARY 6,100,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO DOWN BALLOP ABDULAI IBN ABASS PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY SCHOOL 694 1391-2-02007 6,940,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO TAMBA ABU ABDULAI IBNU MASSOUD ANSARUL ISLAMIC MISPRIMARY SCHOOL 407 1391-2-02009 STREET 4,070,000 5208-2-10866 FREETOWN CITY COUNCIL WEST III PRIMARY ABERDEEN ABERDEEN MUNICIPAL 366 3,660,000 5103-2-09002 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 397 KOSSOH TOWN ABIDING GRACE PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 62 620,000 5103-2-08963 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 373 BENGUEMA ABNAWEE ISLAMIC PRIMARY SCHOOOL PRIMARY 405 4,050,000 4109-2-06695 BO DISTRICT KAKUA 303 KPETEMA ACEF / MOUNT HORED PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 411 10,000.00 4,110,000 Not found WARDC WATERLOO RURAL COLE TOWN ACHIEVERS PRIMARY TUTORAGE PRIMARY 388 3,880,000 ACTION FOR CHILDREN AND YOUTH 5205-2-09766 FREETOWN CITY COUNCIL EAST III CALABA TOWN 460 10,000 DEVELOPMENT PRIMARY 4,600,000 ADA GORVIE MEMORIAL PREPARATORY 320401214 BONTHE DISTRICT IMPERRI MORIBA TOWN 320 10,000 PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 3,200,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO BONGALOW ADULLAM PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY SCHOOL 323 1391-2-01954 3,230,000 1109-2-00266 KAILAHUN DISTRICT LUAWA KAILAHUN ADULLAM PRIMARY