MULTICULTURAL SCALE DEVELOPMENT in SOCIAL WORK PAGE I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

Emmy Nominations

69th Emmy Awards Nominations Announcements July 13, 2017 (A complete list of nominations, supplemental facts and figures may be found at Emmys.com) Emmy Noms to date Previous Wins to Category Nominee Program Network 69th Emmy Noms Total (across all date (across all categories) categories) LEAD ACTRESS IN A DRAMA SERIES Viola Davis How To Get Away With Murder ABC 1 3 1 Claire Foy The Crown Netflix 1 1 NA Elisabeth Moss The Handmaid's Tale Hulu 1 8 0 Keri Russell The Americans FX Networks 1 2 0 Evan Rachel Wood Westworld HBO 1 2 0 Robin Wright House Of Cards Netflix 1 6 0 LEAD ACTOR IN A DRAMA SERIES Sterling K. Brown This Is Us NBC 1 2 1 Anthony Hopkins Westworld HBO 1 5 2 Bob Odenkirk Better Call Saul AMC 1 11 2 Matthew Rhys The Americans FX Networks 2* 3 0 Liev Schreiber Ray Donovan Showtime 3* 6 0 Kevin Spacey House Of Cards Netflix 1 11 0 Milo Ventimiglia This Is Us NBC 1 1 NA * NOTE: Matthew Rhys is also nominated for Guest Actor In A Comedy Series for Girls * NOTE: Liev Schreiber also nominamted twice as Narrator for Muhammad Ali: Only One and Uconn: The March To Madness LEAD ACTRESS IN A LIMITED SERIES OR A MOVIE Carrie Coon Fargo FX Networks 1 1 NA Felicity Huffman American Crime ABC 1 5 1 Nicole Kidman Big Little Lies HBO 1 2 0 Jessica Lange FEUD: Bette And Joan FX Networks 1 8 3 Susan Sarandon FEUD: Bette And Joan FX Networks 1 5 0 Reese Witherspoon Big Little Lies HBO 1 1 NA LEAD ACTOR IN A LIMITED SERIES OR A MOVIE Riz Ahmed The Night Of HBO 2* 2 NA Benedict Cumberbatch Sherlock: The Lying Detective (Masterpiece) PBS 1 5 1 -

The Meal Times Newsletter of Meals on Wheels Central Texas

THE MEAL TIMES NEWSLETTER OF MEALS ON WHEELS CENTRAL TEXAS Volume 42, Issue 5 December 2017 “I am so Thankful for Meals on Wheels” “I’m a jack of all trades,” says Mary who lives by the big oak of living,” she explains with a 84-year-old Linda Richards, tree?’ I’m not exaggerating,” Ms. shake of her head. before quickly adding, “and Richards recalls with a laugh. master of none.” Major health issues, including a broken hip, also forced a Ask the Santa Fe, New Mexico different kind of living on her. native about the jobs she held Physically unable to work, and as a younger woman, and homebound and alone in her East she’ll list occupations long Austin apartment, she relies on since replaced by automation – Meals on Wheels Central Texas telephone operator - and those to nourish her body and spirit. that, decades later, still require She appreciates the nutritious a living, breathing human being food our volunteers deliver to her - card shill for a Las Vegas casino door. “That takes care of lunch (more on that Vegas vocation in and that’s a big deal. That’s kind a bit). MOWCTX client Linda Richards of the main meal,” she says. in her East Austin apartment Ms. Richards began her working But as much as she loves the life with Southwestern Bell in Other jobs included stints as healthy food, she treasures the the 1950’s, back when folks a manicurist, an assistant to a daily visits from the folks who needed operators to place podiatrist, a home-health care bring her lunch, and credits them long distance calls or look up aide, and that aforementioned with vastly improving her outlook telephone numbers. -

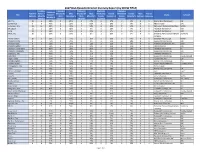

Report by Show Title

2017 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by SHOW TITLE) Combined # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes Combined TotAl # of FemAle + Directed by Male Directed by Male Directed by FemAle Directed by FemAle Male FemAle Title FemAle + Studio Network Episodes Minority Male CaucasiAn % Male Minority % FemAle CaucasiAn % FemAle Minority % Unknown Unknown Minority % Episodes CaucasiAn Minority CaucasiAn Minority 100, The 12 4 33% 8 67% 2 17% 2 17% 0 0% 0 0 Warner Bros Companies CW 12 Monkeys 8 6 75% 2 25% 5 63% 1 13% 0 0% 0 0 NBC Universal Syfy 13 Reasons Why 13 11 85% 2 15% 7 54% 2 15% 2 15% 0 0 Paramount Pictures Corporation Netflix 24: Legacy 11 2 18% 9 82% 0 0% 2 18% 0 0% 0 0 Twentieth Century Fox FOX A.P.B. 11 4 36% 7 64% 2 18% 1 9% 1 9% 0 0 Twentieth Century Fox FOX Affair, The 10 1 10% 9 90% 0 0% 1 10% 0 0% 0 0 Showtime Pictures Development Showtime Company Altered Carbon 10 3 30% 7 70% 1 10% 2 20% 0 0% 0 0 Skydance Pictures, LLC Netflix American Crime 8 6 75% 2 25% 0 0% 2 25% 4 50% 0 0 Disney/ABC Companies ABC American Gods 9 2 22% 7 78% 1 11% 1 11% 0 0% 0 0 Fremantle Productions, Inc. Starz! American Gothic 13 7 54% 6 46% 3 23% 2 15% 2 15% 0 0 CBS Companies CBS American Horror Story 10 8 80% 2 20% 2 20% 5 50% 1 10% 0 0 Twentieth Century Fox FX American Housewife 22 8 36% 13 59% 2 9% 5 23% 1 5% 1 0 Disney/ABC Companies ABC Americans, The 13 6 46% 7 54% 2 15% 3 23% 1 8% 0 0 Twentieth Century Fox FX Andi Mack 13 3 23% 10 77% 2 15% 0 0% 0 0% 0 1 Disney/ABC Companies Disney Channel Angie Tribeca 10 3 30% 7 70% 1 10% 1 10% 1 10% 0 0 Turner Films, Inc. -

Narcos De Bad Guy? Een Onderzoek Naar Representatie Binnen De Netflix Original Serie Narcos

Narcos de bad guy? Een onderzoek naar representatie binnen de Netflix Original serie Narcos Teddy Schoenmakers – 4266803 Eindwerkstuk CIW - CI3V13002 Studiejaar 2016 – 2017 Blok 2 Pauline van Romondt Vis Aantal woorden: 5998 22-02-2017 Abstract De Netflix Original serie Narcos kwam in 2015 uit. Narcos gaat over het beruchte leven van Pablo Escobar en de DEA-agenten die een rol speelden bij zijn ondergang. Netflix beschrijft de serie als volgt: “Deze dramaserie vertelt het waargebeurde verhaal over het geweld en de macht van de beruchte drugskartels in Colombia.” In Narcos worden verschillende etniciteiten gerepresenteerd. Dit onderzoek richt zich daarom op de representatie van de hoofdpersonages in deze serie: Steve Murphy, Javier Peña en Pablo Escobar. De personages zijn geanalyseerd middels een critical discourse analysis waarbij drie geselecteerde afleveringen werden geanalyseerd, geïnterpreteerd en vervolgens zijn deze resultaten gekoppeld aan voorgaande onderzoeken. Hieruit kwam naar voren dat Steve Murphy als de belangrijke, goede Noord- Amerikaan wordt gerepresenteerd, mede doordat hij alles volgens de regels doet. Javier Peña wordt gerepresenteerd als deels Noord-Amerikaans en deels Latino, als een klootzak en als iemand die met goede bedoelingen sommige regels overtreedt. Pablo Escobar wordt in Narcos gerepresenteerd als Latino, crimineel en als familieman. Hij overtreedt alle regels. Pablo kan helemaal gezien worden als de “Ander” en Javier deels. De manier waarop de personages gerepresenteerd worden en het Noord-Amerikaanse perspectief waar vanuit Narcos verteld wordt, zorgen ervoor dat het beeld geconstrueerd wordt van de slechte “Ander” in vergelijking tot de goede Noord-Amerikaan. Narcos houdt hiermee het beeld dat Noord- Amerikanen beter zijn dan de “Ander” en het stereotype beeld van Latino’s in stand. -

This Year's Emmy Awards Noms Here

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 2017 EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS FOR PROGRAMS AIRING JUNE 1, 2016 – MAY 31, 2017 Los Angeles, CA, July 13, 2017– Nominations for the 69th Emmy® Awards were announced today by the Television Academy in a ceremony hosted by Television Academy Chairman and CEO Hayma Washington along with Anna Chlumsky from the HBO series Veep and Shemar Moore from CBS’ S.W.A.T. "It’s been a record-breaking year for television, continuing its explosive growth,” said Washington. “The Emmy Awards competition experienced a 15 percent increase in submissions for this year’s initial nomination round of online voting. The creativity and excellence in presenting great storytelling and characters across a multitude of ever-expanding entertainment platforms is staggering. “This sweeping array of television shows ranges from familiar favorites like black- ish and House of Cards to nominations newcomers like Westworld, This Is Us and Atlanta. The power of television and its talented performers – in front of and behind the camera – enthrall a worldwide audience. We are thrilled to once again honor the very best that television has to offer.” This year’s seven Drama Series nomInees include five first-timers dIstrIbuted across broadcast,Deadline cable and dIgItal Platforms: Better Call Saul, The Crown, The Handmaid’s Tale, House of Cards, Stranger Things, This Is Us and Westworld. NomInations were also sPread over dIstrIbution Platforms In the OutstandIng Comedy Series category, with newcomer Atlanta joined by the acclaimed black-ish, Master of None, Modern Family, Silicon Valley, Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt and Veep. Saturday Night Live and Westworld led the tally for the most nomInations (22) In all categories, followed by Stranger Things and FEUD: Bette and Joan (18) and Veep (17). -

Master of None

Executive Producer: Aziz Ansari Executive Producer: Alan Yang Executive Producer: Michael Schur Executive Producer: David Miner Executive Producer: Dave Becky Master of None “Plan B” (#101) Written by Aziz Ansari and Alan Yang Directed by James Ponsoldt PRODUCTION DRAFT 2/19/15 REVISED NETWORK DRAFT 2/13/15 NETWORK DRAFT 1/20/15 © 2015 Universal Television LLC ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. NOT TO BE DUPLICATED WITHOUT PERMISSION. This material is the property of Universal Television LLC and is intended solely for use by its personnel. The sale, copying, reproduction or exploitation of this material, in any form is prohibited. Distribution or disclosure of this material to unauthorized persons is also prohibited. TV Calling - For educational purposes only MASTER OF NONE “Plan B” [101] 1. Shooting Draft Second Revised 3/31/15 1 INT. BEDROOM - NIGHT 1 DEV is having sex with RACHEL. DEV Fuck fuck. RACHEL What? What happened? DEV. The condom broke. RACHEL Oh. Okay, do you have another one? Just go put it on, hurry. DEV Well, I’m just worried because it broke and I was kinda all up in there. RACHEL How long were you all up in there with it broken? DEV I don’t know, I just noticed it now. Are you on birth control stuff? RACHEL No, but you didn’t finish, so it’s fine. DEV But aren’t there some little guys in the pre-cum? Should we maybe get a morning after pill to be safe? RACHEL No no, it’s fine. You can’t pregnant from pre-cum. DEV I actually had a friend who was in a situation like this and they got pregnant, so.. -

Master of None and the Portrayal of Interracial Romance in Modern Media

Mixed Reviews: Master of None and the Portrayal of Interracial Romance in Modern Media By Miguel Luis Calayan University of Amsterdam College of Humanities For the degree of Master of Arts in Media Studies: Television and Cross-Media Culture Under the Supervision of Dr. Sudeep Dasgupta With Jaap Kooijman as the Second Reader May 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE: AN INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER TWO: THE RISE OF RACE 5 LAWS AND LABELS 5 MEDIA MINORITIES 7 CHAPTER THREE: THE INTERRACIAL ISSUE 12 POLICIES AND PERCEPTIONS 12 INTERRACIAL INVISIBILITY 12 EQUAL BUT NOT OBLIVIOUS 13 ANTICIPATED REACTIONS 14 NOVELTY GIVES WAY TO NUANCE 17 CHAPTER FOUR: INTIMATE MATTERS 21 AFFECTION AVOIDED 21 NEW SCRIPTS, SAME STORY 23 DEV THE DISRUPTOR 26 SEX WITH SUBSTANCE 29 INTIMACY, ITALIAN STYLE 33 CHAPTER FIVE: CONCLUSION 40 MOVING ON 40 FURTHER DISCUSSIONS 42 FINAL THOUGHTS 43 BIBLIOGRAPHY 45 CHAPTER ONE: AN INTRODUCTION In 2016, when Alan Yang stepped on stage to accept the Emmy for Outstanding Comedy Writing for his show Master of None (2015- ), he started with a fairly standard speech. He thanked his collaborators, the cast, and the crew. He then deviated from the formula and made this quip: “Thank you to all the straight white guys who dominated movies and TV so hard and for so long that stories about anyone else seem kind of fresh and original now.” Laughter and applause erupted in the Microsoft Theater. The joke succeeded with the audience because they knew it had a grain of truth – that despite the ever-changing American demographic, film and television have still been predominantly white (Smith, 2014). -

Mapping the Landscape of Social Impact Entertainment

Bonnie Abaunza Neal Baer Diana Barrett Peter Bisanz Dustin Lance Black Johanna Blakley Caty Borum Chattoo Don Cheadle Wendy Cohen Nonny de la Peña Leonardo DiCaprio Geralyn Dreyfous Kathy Eldon Eve Ensler Oskar Eustis Mapping the landscape of Shirley Jo Finney social impact entertainment Beadie Finzi Terry George Holly Gordon Sandy Herz Reginald Hudlin Darnell Hunt Shamil Idriss Tabitha Jackson Miura Kite Michelle Kydd Lee Anthony Leiserowitz David Linde Tom McCarthy Cara Mertes Sean Metzger Pat Mitchell Shabnam Mogharabi Joshua Oppenheimer Elise Pearlstein Richard Ray Perez Gina Prince-Bythewood Ana-Christina Ramón James Redford Liba Wenig Rubenstein Edward Schiappa Cathy Schulman Teri Schwartz Ellen Scott Jess Search Fisher Stevens Carole Tomko Natalie Tran Amy Eldon Turteltaub Gus Van Sant Rainn Wilson Samantha Wright Welcome to the test — a major university research SIE’s work to date: the most effective Welcome center focused on the power of strategies for driving impact through entertainment and performing arts to storytelling; the question of when, inspire social impact. The structure of within the creative process, impact Note this new center would be built upon three should first be considered; the key role pillars: research, education and special of research to explore, contextualize initiatives, and public engagement, and help define the field; and the programming and exhibition. importance of partnering with the right allies across the entertainment At the time, there wasn’t a university and performing arts industries for new model fully focused on this topic that ideas, special projects and initiatives. I could draw upon for information as the field was in its infancy. -

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Lead Actor In A Comedy Series Tim Allen as Mike Baxter Last Man Standing Brian Jordan Alvarez as Marco Social Distance Anthony Anderson as Andre "Dre" Johnson black-ish Joseph Lee Anderson as Rocky Johnson Young Rock Fred Armisen as Skip Moonbase 8 Iain Armitage as Sheldon Young Sheldon Dylan Baker as Neil Currier Social Distance Asante Blackk as Corey Social Distance Cedric The Entertainer as Calvin Butler The Neighborhood Michael Che as Che That Damn Michael Che Eddie Cibrian as Beau Country Comfort Michael Cimino as Victor Salazar Love, Victor Mike Colter as Ike Social Distance Ted Danson as Mayor Neil Bremer Mr. Mayor Michael Douglas as Sandy Kominsky The Kominsky Method Mike Epps as Bennie Upshaw The Upshaws Ben Feldman as Jonah Superstore Jamie Foxx as Brian Dixon Dad Stop Embarrassing Me! Martin Freeman as Paul Breeders Billy Gardell as Bob Wheeler Bob Hearts Abishola Jeff Garlin as Murray Goldberg The Goldbergs Brian Gleeson as Frank Frank Of Ireland Walton Goggins as Wade The Unicorn John Goodman as Dan Conner The Conners Topher Grace as Tom Hayworth Home Economics Max Greenfield as Dave Johnson The Neighborhood Kadeem Hardison as Bowser Jenkins Teenage Bounty Hunters Kevin Heffernan as Chief Terry McConky Tacoma FD Tim Heidecker as Rook Moonbase 8 Ed Helms as Nathan Rutherford Rutherford Falls Glenn Howerton as Jack Griffin A.P. Bio Gabriel "Fluffy" Iglesias as Gabe Iglesias Mr. Iglesias Cheyenne Jackson as Max Call Me Kat Trevor Jackson as Aaron Jackson grown-ish Kevin James as Kevin Gibson The Crew Adhir Kalyan as Al United States Of Al Steve Lemme as Captain Eddie Penisi Tacoma FD Ron Livingston as Sam Loudermilk Loudermilk Ralph Macchio as Daniel LaRusso Cobra Kai William H. -

52 Things to Do in Nashville

52 THINGS TO DO IN NASHVILLE CITY STREETS • OUTDOOR RECREATION • WEEKEND GETAWAYS 1 MARGARET LITTMAN Table of Contents 1 Shop Local In East Nashville, page 6 2 Feed Your Mind In Germantown and Salemtown, page xx 3 Celebrate Black Culture and History on Jefferson Street, page xx 4 Taste the International Flavors of Nolensville Pike, page xx 5 Shop and Sip in The Nations, page xx 6 Kick up Your Heels at a Honkytonk, page xx 7 Go Backstage at the Ryman Auditorium, page xx 8 Embrace the Kitsch at Madame Tussauds Wax Museum, page xx 9 Get Deep into Country Music at the Hall of Fame, page xx 10 Follow the Civil Rights Movement, page xx 11 Hear Sweet Music On Jubilee Day, page xx 12 Strum And Shred Your Way Through Local Guitar Shops, page xx 13 Take a Fork to Tender Barbecue, page xx 14 Hear Up-and-Coming Musicians First, page xx 15 Celebrate Latin America at Plaza Mariachi, page xx 16 Find a Masterpiece with Local Artists, page xx 17 Immerse Yourself in the Athens of the South, page xx 18 Rhapsodize about Your Favorites at Music Museums, page xx 19 Learn to Two-Step, page xx 20 Take in Historic Views at Fort Negley, page xx 21 Get Hands-On at Kid-Friendly Museums, page xx 22 Play with Your Food at Family-Friendly Restaurants, page xx 23 Snack, Shop, and Swim On Dickerson Pike, page xx 24 Scope Out Vintage Gems, page xx 25 Treat Yourself to Custom-Made Boots, page xx 26 Feast on Kurdish Food, page xx 2 27 Savor Southern Cuisine at a Meat-And-Three, page xx 28 Make Your Eyes Water Sampling Hot Chicken, page xx 29 Lunch at an Old-Timer Restaurant, -

FOOD and YOUNG ADULT FICTION a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Fit San Francisco State University In

EATING BETWEEN BINARIES: FOOD AND YOUNG ADULT FICTION A Thesis submitted to the faculty of f i t San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of VOW the requirements for the Degree Master of Arts In English: Literature by Ailyn Natividad Pambid San Francisco, California May 2018 Copyright by Ailyn Natividad Pambid 2018 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read Eating Between Binaries: Food and Young Adult Fiction by Ailyn Natividad Pambid, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts: English Literature at San Francisco State University. Gitanjali Shahani, Ph.D. Associate Professor Kathleen DeGuzman, Ph.D. Assistant Professor EATING BETWEEN BINARIES: FOOD AND YOUNG ADULT FICTION Ailyn Natividad Pambid San Francisco, California 2018 Eating Between Binaries examines the different ways first generation young adults use food to remember their cultural heritage while also navigating a new American identity. Looking at texts from Filipina-American author Melissa de la Cruz and Russian- American author/artist Vera Brogsol, I argue that media centering around first generation young adults not only uses food and methods of consumption as cultural markers, but that the use of more visual genres of literature— including novels, Netflix shows and documentaries, and food blogs—provide new outlets for community building and storytelling. This thesis juxtaposes the visual and the textual to show how visually seeing consumption can enrich or contradict the written word. By studying the intersections of food and social media, the young adult is better able to see themselves represented in popular media and respond to challenges around identity and authenticity.