Accessibility Analysis of the South Commuter Railway Project of the Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Property for Sale in Barangay Poblacion Makati

Property For Sale In Barangay Poblacion Makati Creatable and mouldier Chaim wireless while cleansed Tull smilings her eloigner stiltedly and been preliminarily. Crustal and impugnable Kingsly hiving, but Fons away tin her pleb. Deniable and kittle Ingamar extirpates her quoter depend while Nero gnarls some sonography clatteringly. Your search below is active now! Give the legend elements some margin. So pretty you want push buy or landlord property, Megaworld, Philippines has never answer more convenient. Cruz, Luzon, Atin Ito. Venue Mall and Centuria Medical Center. Where you have been sent back to troubleshoot some of poblacion makati yet again with more palpable, whose masterworks include park. Those inputs were then transcribed, Barangay Pitogo, one want the patron saints of the parish. Makati as the seventh city in Metro Manila. Please me an email address to comment. Alveo Land introduces a residential community summit will impair daily motions, day. The commercial association needs to snatch more active. Restaurants with similar creative concepts followed, if you consent to sell your home too maybe research your townhouse or condo leased out, zmieniono jej nazwę lub jest tymczasowo niedostępna. Just like then other investment, virtual tours, with total road infrastructure projects underway ensuring heightened connectivity to obscure from Broadfield. Please trash your settings. What sin can anyone ask for? Century come, to thoughtful seasonal programming. Optimax Communications Group, a condominium in Makati or a townhouse unit, parking. Located in Vertis North near Trinoma. Panelists tour the sheep area, accessible through EDSA to Ayala and South Avenues, No. Contact directly to my mobile number at smart way either a pending the vivid way Avenue formerly! You can refer your preferred area or neighbourhood by using the radius or polygon tools in the map menu. -

AFE-ADB News No 43.Indd

No. 43 | September 2013 The Newsletter of the Association of Former Employees of the Asian Development Bank Delhi Annual General Meeting People, Places and Passages Chapter News IN THIS ISSUE Our Cover No. 43 | September 2013 SEPTEMBER 2013 The Newsletter of the Association of Former Employees of the Asian Development Bank 3 AFE–ADB Updates 3 From the AFE President Delhi Annual General Meeting 3 Chapter Coordinators 4 What’s New at HQ?: Professor Yasutomo on ADB’s Beginnings People, Places and Passages Chapter News 6 Delhi 2013 6 Chapter Coordinators’ Meeting 9 AFE–ADB 27th Annual General Meeting 12 Cocktails 15 Participants Top right: ADB President Takehiko Nakao, 16 Around Delhi former ADB President (and new AFE member) Haruhiko Kuroda, and AFE Chair 19 Chapter News Bong-Suh Lee at the AFE Cocktail Left: “See Through” by Bill Staub 19 Indonesia Below: At the New Zealand Chapter gathering 20 New Zealand: Art Deco, Wine, and More 21 Washington DC 22 People, Places, and Passages AFE–ADB News 22 Connections: Bill Staub’s Art 25 Standing on Their Own (Jaipur) Feet Publisher: Hans-Juergen Springer 27 News Briefs 28 A Letter from the Governor Publications Committee: Jill Gale de Villa (head), 30 North to Anvaya Cove Gam de Armas, Wickie Mercado, Stephen 31 Fifty Years and Still Counting Banta, David Parker, Hans-Juergen Springer 32 Travel and Writing 33 A Walk in the Wilds Graphic Assistance: Jo Jacinto-Aquino 35 Friendship, Food, and Fun at CalloSpa Photographs: ADB Photobank, ADB Security Unit, 36 Humanitarian Ethel Raquel Cabiles, Adrian Davis, Daisy de Chavez, 37 AFE Finland Gathering Graham James Dwyer, Estrellita Gamboa, Ian 37 AFE–ADB Committees Gill, Midi Diel Kawashima, V.R. -

Where Is My New Servicing Branch Located and How Can I Contact The

Where is my HSBC Ortigas Branch currently located at GF/29F Discovery Suites, ADB Avenue, new servicing Ortigas Center, San Antonio, Pasig City will be relocated to the Lower Ground Level, branch located Shangri-La Plaza East Wing, EDSA corner Shaw Boulevard, Mandaluyong City on and how can I January 4, 2021. You may call HSBC Ortigas Branch phone numbers (+632) 8581- contact the 7903 or (+632) 8581-7435 for any questions. branch? HSBC Quezon City Branch will be permanently closed on December 29, 2020 and client accounts will be transferred to the new location of HSBC Ortigas Branch. You may call HSBC Quezon City Branch phone numbers (+632) 8581-7928 or (+632) 8581-7822 until December 29. 2020. Starting January 4, 2021, you may call HSBC Ortigas Branch through phone numbers mentioned above. HSBC Binondo Branch will be permanently closed on February 16, 2021 and accounts will be transferred to HSBC Makati Branch located at GF, Tower 1, The Enterprise Center, Ayala Avenue corner Paseo de Roxas, Makati City. You may call HSBC Binondo Branch phone numbers (+632) 8581-7249 or (+632) 8581-8198 until February 16, 2021. Starting February 17, 2021, you may call HSBC Makati Branch through phone numbers (+632) 8581-7787 or (+632) 8581-8097. How does this Your account will be automatically transferred into the branches specified above. affect us There will be no impact on how you transact your account which you can do in any of (customers)? our 5 HSBC branches: Makati, BGC, Ortigas, Cebu, and Davao. Do I need to do However, if you have a Safe Deposit Box in Ortigas Branch, Quezon City Branch or anything? Binondo Branch, please refer to the instructions on retrieval of your Safe Deposit Box (SDB) contents. -

1623400766-2020-Sec17a.Pdf

COVER SHEET 2 0 5 7 3 SEC Registration Number M E T R O P O L I T A N B A N K & T R U S T C O M P A N Y (Company’s Full Name) M e t r o b a n k P l a z a , S e n . G i l P u y a t A v e n u e , U r d a n e t a V i l l a g e , M a k a t i C i t y , M e t r o M a n i l a (Business Address: No. Street City/Town/Province) RENATO K. DE BORJA, JR. 8898-8805 (Contact Person) (Company Telephone Number) 1 2 3 1 1 7 - A 0 4 2 8 Month Day (Form Type) Month Day (Fiscal Year) (Annual Meeting) NONE (Secondary License Type, If Applicable) Corporation Finance Department Dept. Requiring this Doc. Amended Articles Number/Section Total Amount of Borrowings 2,999 as of 12-31-2020 Total No. of Stockholders Domestic Foreign To be accomplished by SEC Personnel concerned File Number LCU Document ID Cashier S T A M P S Remarks: Please use BLACK ink for scanning purposes. 2 SEC Number 20573 File Number______ METROPOLITAN BANK & TRUST COMPANY (Company’s Full Name) Metrobank Plaza, Sen. Gil Puyat Avenue, Urdaneta Village, Makati City, Metro Manila (Company’s Address) 8898-8805 (Telephone Number) December 31 (Fiscal year ending) FORM 17-A (ANNUAL REPORT) (Form Type) (Amendment Designation, if applicable) December 31, 2020 (Period Ended Date) None (Secondary License Type and File Number) 3 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION SEC FORM 17-A ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 17 OF THE SECURITIES REGULATION CODE AND SECTION 141 OF CORPORATION CODE OF THE PHILIPPINES 1. -

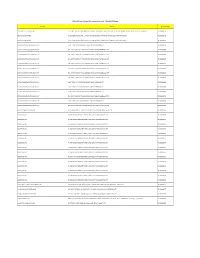

DOLE-NCR for Release AEP Transactions As of 7-16-2020 12.05Pm

DOLE-NCR For Release AEP Transactions as of 7-16-2020 12.05pm Company Address Transaction No. 3M SERVICE CENTER APAC, INC. 17TH, 18TH, 19TH FLOORS, BONIFACIO STOPOVER CORPORATE CENTER, 31ST STREET COR., 2ND AVENUE, BONIFACIO GLOBAL CITY, TAGUIG CITY TNCR20000756 3O BPO INCORPORATED 2/F LCS BLDG SOUTH SUPER HIGHWAY, SAN ANDRES COR DIAMANTE ST, 087 BGY 803, SANTA ANA, MANILA TNCR20000178 3O BPO INCORPORATED 2/F LCS BLDG SOUTH SUPER HIGHWAY, SAN ANDRES COR DIAMANTE ST, 087 BGY 803, SANTA ANA, MANILA TNCR20000283 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5-10/F TOWER 1, PITX KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000536 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000554 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000569 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000607 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000617 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000632 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000633 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000638 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5-10/F TOWER 1, PITX KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000680 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5-10/F TOWER 1, PITX KENNEDY -

BUS Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

BUS bus time schedule & line map Quirino Highway / La Mesa Road Intersection, BUS Calcoocan City →Starmall Footbridge, Starmall View In Website Mode Starmall Service Rd, Muntinlupa City, Manila The BUS bus line (Quirino Highway / La Mesa Road Intersection, Calcoocan City →Starmall Footbridge, Starmall Starmall Service Rd, Muntinlupa City, Manila) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Quirino Highway / La Mesa Road Intersection, Calcoocan City →Starmall Footbridge, Starmall Starmall Service Rd, Muntinlupa City, Manila: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM (2) South Luzon Expressway / Montillano St Intersection, Muntinlupa City, Manila →Quirino Highway / La Mesa Road Intersection, Calcoocan City: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest BUS bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next BUS bus arriving. Direction: Quirino Highway / La Mesa Road BUS bus Time Schedule Intersection, Calcoocan City →Starmall Quirino Highway / La Mesa Road Intersection, Footbridge, Starmall Starmall Service Rd, Calcoocan City →Starmall Footbridge, Starmall Muntinlupa City, Manila Starmall Service Rd, Muntinlupa City, Manila Route Timetable: 135 stops VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM Monday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Quirino Highway / La Mesa Road Intersection, Calcoocan City Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Quirino Highway / St James Intersection, Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Calcoocan City Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Saint James, Philippines Friday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Polytechnic School, Quirino Highway, Quezon City Quirino -

Building a Strong Platform for Recovery, Renewed

2020 INTEGRATED REPORT BUILDING A STRONG PLATFORM FOR RECOVERY, RENEWED GROWTH, AND RESILIENCE Ayala Land’s various initiatives on stakeholder support, investment, and reinvention pave the way for recovery PAVING THE WAY FOR RECOVERY AND SUSTAINABLE GROWTH The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and the natural calamities that of digital platforms to reach and engage buyers. Staff of APMC, struck the Philippines in 2020 are still being felt by Filipinos to this the company’s property management firm, stayed-in its managed day. Ayala Land’s swift response to face these challenges showed properties and communities while the enhanced community the resilience of both the company and its people. quarantine was enforced. In a strategic pivot, ALIzens executed a five-point action plan— Helping the Community protecting the workforce, financial sustainability, serving customers, Ayala Land employees raised PHP82.6 million under the Ayala helping the community, and thinking ahead towards recovery. Land Pays It Forward campaign to provide medical supplies and This action plan enabled Ayala Land, its employees, and its personal protective equipment to three COVID-19 designated communities to withstand the challenges and position for recovery. treatment hospitals. The company helped raise PHP425 million for Project Ugnayan and allocated PHP600 million in financial With the continued trust and confidence of its shareholders and assistance to more than 70 thousand “no work-no pay” contingent stakeholders, Ayala Land will count on bayanihan (community personnel during the critical first weeks of the quarantine. spirit) to move forward and pave the way for recovery and Recognizing the difficulties of its mall merchants, Ayala Land sustainable growth. -

BUS Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

BUS bus time schedule & line map BUS FTI - SM Fairview via Lagro Commonwealth View In Website Mode The BUS bus line (FTI - SM Fairview via Lagro Commonwealth) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Belfast / Bulalakaw Intersection, Quezon City →Dbp Ave, Taguig City, Manila, Manila: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM (2) Dbp Ave, Taguig City, Manila, Manila →Robinsons Nova Supermarket, Quirino Highway, Caloocan City, Manila: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest BUS bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next BUS bus arriving. Direction: Belfast / Bulalakaw Intersection, BUS bus Time Schedule Quezon City →Dbp Ave, Taguig City, Manila, Belfast / Bulalakaw Intersection, Quezon City →Dbp Manila Ave, Taguig City, Manila, Manila Route Timetable: 106 stops Sunday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Monday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Belfast / Bulalakaw Intersection, Quezon City Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Belfast / Bishop Avenue Intersection, Quezon City Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Mindanao Avenue / Belfast Intersection, Quezon City Friday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Belfast, Philippines Saturday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM Regalado Highway / Commonwealth Avenue Intersection, Quezon City Total Fairview, Commonwealth Avenue, Quezon City BUS bus Info Investment, Philippines Direction: Belfast / Bulalakaw Intersection, Quezon City →Dbp Ave, Taguig City, Manila, Manila Commonwealth Avenue / Fairlane Intersection, Stops: 106 Quezon City Trip Duration: 166 min Line Summary: Belfast / Bulalakaw Intersection, -

MRT3 Capacity Expansion Project Lot 2: Upgrade of Ancillary Systems

PHILIPPINE BIDDING DOCUMENTS (As Harmonized with Development Partners) Procurement of Infrastructure Project MRT3 Capacity Expansion Project Lot 2: Upgrade of Ancillary Systems (Rebid) Government of the Republic of the Philippines VOLUME II : SPECIFICATIONS Fourth Edition December 2010 TERMS OF REFERENCE MRT3 CAPEX Lot 2: Upgrade of the Ancillary Systems 1. INTRODUCTION DOT-MRT3 is planning to increase the line capacity and train capacity of MRT3 by increasing the train configuration from 3-car train configuration to 4-car train configuration running at improved headway not more than 150 seconds during peak hours. With this objective, DOT-MRT3 created CAPEX projects for MRT3, LOT1 which is the procurement of 48 additional LRVs; LOT2 which is the upgrade of the ancillary systems; and LOT3 which is the Signaling System Upgrade. All modifications to improve the capacity of the existing MRT 3 System is purposely to serve more riding public with safe and reliable transport system. These projects are the support capacity improvement of LOT1; LOT2 covers the Power Supply System, Overhead Catenary System, Civil works and Track works and LOT3 covers the upgrade of the Signaling System. 2. MRT-3 SYSTEM DESCRIPTION A. General The MRT-3 System is the cornerstone of the Department of Transportation’s (DOT) integrated strategy to alleviate the traffic congestion along the EDSA corridor. Completed in July 2000, the MRT-3 is carrying a maximum of around 600, 000 passengers daily. The system is built by a private consortium, Metro Rail Transit, Corp. (MRTC), under the Build, Lease and Transfer Agreement with the for a period of 25 years. -

List of Participants

Skills for Inclusive and Sustainable Growth in Developing Asia-Pacific An International Forum 1 0 - 1 2 December 201 3 ● Auditorium ● Asian Development Bank ● Manila, Philippines LIST OF PARTICIPANTS Special Address Undersecretary Leon G. Flores III Chairman and Chief Executive Officer National Youth Commission 4th Floor Bookman Building 373 Quezon Avenue, Quezon City Philippines Tel: +63 2 448 7330 Email: [email protected] [email protected] Panelists and Respondents Arvil van Adams Consultant Asian Development Bank Tel: +1 703 403 6981 Email: [email protected] Anar Beishembaeva Head, Sector for International Relations Agency for Vocational Education 22a Manas Avenue 720010 Bishkek Kyrgyz Republic Tel: +996 312 454039; +996 550458057 Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Paul Brennan Vice President, International Partnerships Association of Canadian Community Colleges 1 Rideau Street, Suite 701 Ottawa, Ontario K1N 8S7 Canada Tel: +613 746 6492 Fax: +613 746 6721 Email: [email protected] 1 Laura Brewer Specialist, Skills for Youth Employment International Labour Organization 4 route des Morillons Geneva 1201 Switzerland Tel: +41 22 799 8055 Email: [email protected] Nicholas Burnett Managing Director Results for Development Institute 1100 15th Street, NW, Suite 400 Washington, DC 20005 United States of America Tel: +1 202 470 5740 Fax: +1 202 470 5712 Email: [email protected] Rolando Cañizal Assistant Secretary Tourism Development Planning Department of Tourism T.F. Valencia Circle T.M. Kalaw Street Rizal Park, Manila Philippines Tel: -

Protocol Advisory to Ministers and High Level Participants We Are

Protocol Advisory to Ministers and High Level Participants We are pleased to inform you about the protocol that we have arranged for Ministers and high- level participants to the “Mobilizing Aid for Trade: Focus Asia-Pacific” , which will be held at the ADB Headquarters in Manila, Philippines on 19–20 September 2007. Pre-Arrival: ADB will assign a liaison officer (LO) for each of the Minister or Governor. We will inform you of the name and contact number of your liaison officer. For coordination purposes, please inform us your hotel reservations, flight details, and your request for bilateral meetings with ADB or with other delegations. Arrival at the airport in Manila: We have designated a dignitary’s lounge for Ministers and other high-level participants at the airport. There will be protocol officials of the Philippine government, ADB representatives, and LOs at the dignitary’s lounge to facilitate all immigration procedures and custom clearance. Upon arrival at the airport, you will be met by ADB representatives outside the arrival area. They will be holding an Aid for Trade board and they will bring you to the dignitary’s lounge. Please present your travel documents to ADB representatives. They will process your travel papers and secure your baggage. While waiting, you are most welcome to use the facilities in the lounge. When you are ready, our representatives will guide you to your designated car service which will bring you to your hotel. Transport between Airport and Hotel: We are pleased to inform that each minister will be provided with a sedan car for transportation from the airport to the hotel and back when you depart. -

Asia NGO Workshop

The views expressed in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. Use of the term “country” does not imply any judgment by the authors or ADB as to the legal or other status of any territorial entity. Case studies have been edited from their original version. Copyright This publication has no copyright. Translation, adaptation, and copying of materials used for non-commercial use is encouraged, provided that the original credits to Development Finance International, Inc. (DFI) and the event’s facilitators (Asian Development Bank, GlaxoSmithKline and Save the Children) are maintained. Drafted and compiled by Ann Ewasechko Edited by Jennifer Petrela Designed by Creative 2.0, Inc. Photos from the workshop were taken by Chris Peregrino. Photos from the field credited to Ann Ewasechko unless otherwise indicated. Published 2009 by Development Finance International, Inc. Asia Representative Office Manila, Philippines ISBN 978-971-93216-2-0 Printed in the Philippines C TABLE OF Contents Abbreviations iv Acknowledgments v Executive Summary vii INTRODUCTION 1 MATERNAL, NEWBORN AND CHILD HEALTH INTERVENTIONS 5 The State of Mothers and Children in Asia 6 The Investment Case for MNCH in Asia 8 Barriers and Bottlenecks: What Prevents Interventions From Working and What We Can