Money Market Futures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interest Rate Options

Interest Rate Options Saurav Sen April 2001 Contents 1. Caps and Floors 2 1.1. Defintions . 2 1.2. Plain Vanilla Caps . 2 1.2.1. Caplets . 3 1.2.2. Caps . 4 1.2.3. Bootstrapping the Forward Volatility Curve . 4 1.2.4. Caplet as a Put Option on a Zero-Coupon Bond . 5 1.2.5. Hedging Caps . 6 1.3. Floors . 7 1.3.1. Pricing and Hedging . 7 1.3.2. Put-Call Parity . 7 1.3.3. At-the-money (ATM) Caps and Floors . 7 1.4. Digital Caps . 8 1.4.1. Pricing . 8 1.4.2. Hedging . 8 1.5. Other Exotic Caps and Floors . 9 1.5.1. Knock-In Caps . 9 1.5.2. LIBOR Reset Caps . 9 1.5.3. Auto Caps . 9 1.5.4. Chooser Caps . 9 1.5.5. CMS Caps and Floors . 9 2. Swap Options 10 2.1. Swaps: A Brief Review of Essentials . 10 2.2. Swaptions . 11 2.2.1. Definitions . 11 2.2.2. Payoff Structure . 11 2.2.3. Pricing . 12 2.2.4. Put-Call Parity and Moneyness for Swaptions . 13 2.2.5. Hedging . 13 2.3. Constant Maturity Swaps . 13 2.3.1. Definition . 13 2.3.2. Pricing . 14 1 2.3.3. Approximate CMS Convexity Correction . 14 2.3.4. Pricing (continued) . 15 2.3.5. CMS Summary . 15 2.4. Other Swap Options . 16 2.4.1. LIBOR in Arrears Swaps . 16 2.4.2. Bermudan Swaptions . 16 2.4.3. Hybrid Structures . 17 Appendix: The Black Model 17 A.1. -

Tax Treatment of Derivatives

United States Viva Hammer* Tax Treatment of Derivatives 1. Introduction instruments, as well as principles of general applicability. Often, the nature of the derivative instrument will dictate The US federal income taxation of derivative instruments whether it is taxed as a capital asset or an ordinary asset is determined under numerous tax rules set forth in the US (see discussion of section 1256 contracts, below). In other tax code, the regulations thereunder (and supplemented instances, the nature of the taxpayer will dictate whether it by various forms of published and unpublished guidance is taxed as a capital asset or an ordinary asset (see discus- from the US tax authorities and by the case law).1 These tax sion of dealers versus traders, below). rules dictate the US federal income taxation of derivative instruments without regard to applicable accounting rules. Generally, the starting point will be to determine whether the instrument is a “capital asset” or an “ordinary asset” The tax rules applicable to derivative instruments have in the hands of the taxpayer. Section 1221 defines “capital developed over time in piecemeal fashion. There are no assets” by exclusion – unless an asset falls within one of general principles governing the taxation of derivatives eight enumerated exceptions, it is viewed as a capital asset. in the United States. Every transaction must be examined Exceptions to capital asset treatment relevant to taxpayers in light of these piecemeal rules. Key considerations for transacting in derivative instruments include the excep- issuers and holders of derivative instruments under US tions for (1) hedging transactions3 and (2) “commodities tax principles will include the character of income, gain, derivative financial instruments” held by a “commodities loss and deduction related to the instrument (ordinary derivatives dealer”.4 vs. -

An Analysis of OTC Interest Rate Derivatives Transactions: Implications for Public Reporting

Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports An Analysis of OTC Interest Rate Derivatives Transactions: Implications for Public Reporting Michael Fleming John Jackson Ada Li Asani Sarkar Patricia Zobel Staff Report No. 557 March 2012 Revised October 2012 FRBNY Staff REPORTS This paper presents preliminary fi ndings and is being distributed to economists and other interested readers solely to stimulate discussion and elicit comments. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and are not necessarily refl ective of views at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors. An Analysis of OTC Interest Rate Derivatives Transactions: Implications for Public Reporting Michael Fleming, John Jackson, Ada Li, Asani Sarkar, and Patricia Zobel Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 557 March 2012; revised October 2012 JEL classifi cation: G12, G13, G18 Abstract This paper examines the over-the-counter (OTC) interest rate derivatives (IRD) market in order to inform the design of post-trade price reporting. Our analysis uses a novel transaction-level data set to examine trading activity, the composition of market participants, levels of product standardization, and market-making behavior. We fi nd that trading activity in the IRD market is dispersed across a broad array of product types, currency denominations, and maturities, leading to more than 10,500 observed unique product combinations. While a select group of standard instruments trade with relative frequency and may provide timely and pertinent price information for market partici- pants, many other IRD instruments trade infrequently and with diverse contract terms, limiting the impact on price formation from the reporting of those transactions. -

The Feasibility of Farm Revenue Insurance in Australia

THE FEASIBILITY OF FARM REVENUE INSURANCE IN AUSTRALIA Miranda P.M. Meuwissen1, Ruud B.M. Huirne1, J. Brian Hardaker1/2 1 Department of Economics and Management, Wageningen Agricultural University, The Netherlands 2 Graduate School of Agricultural and Resource Economics, University of New England, Australia ABSTRACT Arrow (1965) stated that making markets for trading risk more complete can be socially beneficial. Within this perspective, we discuss the feasibility of farm revenue insurance for Australian agriculture. The feasibility is first discussed from an insurer's point of view. Well-known problems of moral hazard, adverse selection and systemic risk are central. Then, the feasibility is studied from a farmer’s point of view. A simulation model illustrates that gross revenue insurance can be both cheaper and more effective than separate price and yield insurance schemes. We argue that due to the systemic nature of price and yields risks within years and the positive correlation between years, some public- private partnership for reinsurance may be necessary for insurers to enter the gross revenue insurance market. Pros and cons of alternative forms of a public-private partnership are discussed. Once insurers can deal with the systemic risk problem, we conclude that there are opportunities for crop gross revenue insurance schemes, especially if based on area yields and on observed spot market prices. For insurance schemes to cover individual farmer’s yields and prices, we regard the concept of coinsurance as crucial. With respect to livestock commodities, we argue that yields are difficult to include in an insurance scheme and we propose aspects of further research in the field of price and rainfall insurance. -

Panagora Global Diversified Risk Portfolio General Information Portfolio Allocation

March 31, 2021 PanAgora Global Diversified Risk Portfolio General Information Portfolio Allocation Inception Date April 15, 2014 Total Assets $254 Million (as of 3/31/2021) Adviser Brighthouse Investment Advisers, LLC SubAdviser PanAgora Asset Management, Inc. Portfolio Managers Bryan Belton, CFA, Director, Multi Asset Edward Qian, Ph.D., CFA, Chief Investment Officer and Head of Multi Asset Research Jonathon Beaulieu, CFA Investment Strategy The PanAgora Global Diversified Risk Portfolio investment philosophy is centered on the belief that risk diversification is the key to generating better risk-adjusted returns and avoiding risk concentration within a portfolio is the best way to achieve true diversification. They look to accomplish this by evaluating risk across and within asset classes using proprietary risk assessment and management techniques, including an approach to active risk management called Dynamic Risk Allocation. The portfolio targets a risk allocation of 40% equities, 40% fixed income and 20% inflation protection. Portfolio Statistics Portfolio Composition 1 Yr 3 Yr Inception 1.88 0.62 Sharpe Ratio 0.6 Positioning as of Positioning as of 0.83 0.75 Beta* 0.78 December 31, 2020 March 31, 2021 Correlation* 0.87 0.86 0.79 42.4% 10.04 10.6 Global Equity 43.4% Std. Deviation 9.15 24.9% U.S. Stocks 23.6% Weighted Portfolio Duration (Month End) 9.0% 8.03 Developed non-U.S. Stocks 9.8% 8.5% *Statistic is measured against the Dow Jones Moderate Index Emerging Markets Equity 10.0% 106.8% Portfolio Benchmark: Nominal Fixed Income 142.6% 42.0% The Dow Jones Moderate Index is a composite index with U.S. -

Interest Rate Swap Contracts the Company Has Two Interest Rate Swap Contracts That Hedge the Base Interest Rate Risk on Its Two Term Loans

$400.0 million. However, the $100.0 million expansion feature may or may not be available to the Company depending upon prevailing credit market conditions. To date the Company has not sought to borrow under the expansion feature. Borrowings under the Credit Agreement carry interest rates that are either prime-based or Libor-based. Interest rates under these borrowings include a base rate plus a margin between 0.00% and 0.75% on Prime-based borrowings and between 0.625% and 1.75% on Libor-based borrowings. Generally, the Company’s borrowings are Libor-based. The revolving loans may be borrowed, repaid and reborrowed until January 31, 2012, at which time all amounts borrowed must be repaid. The revolver borrowing capacity is reduced for both amounts outstanding under the revolver and for letters of credit. The original term loan will be repaid in 18 consecutive quarterly installments which commenced on September 30, 2007, with the final payment due on January 31, 2012, and may be prepaid at any time without penalty or premium at the option of the Company. The 2008 term loan is co-terminus with the original 2007 term loan under the Credit Agreement and will be repaid in 16 consecutive quarterly installments which commenced June 30, 2008, plus a final payment due on January 31, 2012, and may be prepaid at any time without penalty or premium at the option of Gartner. The Credit Agreement contains certain customary restrictive loan covenants, including, among others, financial covenants requiring a maximum leverage ratio, a minimum fixed charge coverage ratio, and a minimum annualized contract value ratio and covenants limiting Gartner’s ability to incur indebtedness, grant liens, make acquisitions, be acquired, dispose of assets, pay dividends, repurchase stock, make capital expenditures, and make investments. -

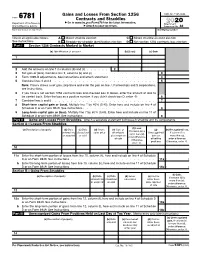

Form 6781 Contracts and Straddles ▶ Go to for the Latest Information

Gains and Losses From Section 1256 OMB No. 1545-0644 Form 6781 Contracts and Straddles ▶ Go to www.irs.gov/Form6781 for the latest information. 2020 Department of the Treasury Attachment Internal Revenue Service ▶ Attach to your tax return. Sequence No. 82 Name(s) shown on tax return Identifying number Check all applicable boxes. A Mixed straddle election C Mixed straddle account election See instructions. B Straddle-by-straddle identification election D Net section 1256 contracts loss election Part I Section 1256 Contracts Marked to Market (a) Identification of account (b) (Loss) (c) Gain 1 2 Add the amounts on line 1 in columns (b) and (c) . 2 ( ) 3 Net gain or (loss). Combine line 2, columns (b) and (c) . 3 4 Form 1099-B adjustments. See instructions and attach statement . 4 5 Combine lines 3 and 4 . 5 Note: If line 5 shows a net gain, skip line 6 and enter the gain on line 7. Partnerships and S corporations, see instructions. 6 If you have a net section 1256 contracts loss and checked box D above, enter the amount of loss to be carried back. Enter the loss as a positive number. If you didn’t check box D, enter -0- . 6 7 Combine lines 5 and 6 . 7 8 Short-term capital gain or (loss). Multiply line 7 by 40% (0.40). Enter here and include on line 4 of Schedule D or on Form 8949. See instructions . 8 9 Long-term capital gain or (loss). Multiply line 7 by 60% (0.60). Enter here and include on line 11 of Schedule D or on Form 8949. -

Securitization of Insurance Liabilities

RECORD OF SOCIETY OF ACTUARIES 1995 VOL. 21 NO. 2 SECURITIZATION OF INSURANCE LIABILITIES Instructors: HANS B!2HLMANN* SAMUEL H. COX Recorder: SAMUEL H. COX Securitization of insurance liabilities allows capital to enter insurance markets more efficiently by establishing insurance-based securities. The mortgage market has been securitized, and it may be possible to make a similar market for insurance liabilities. This should be of interest to actuaries working in reinsurance (the Chicago Board of Trade options are in direct competition with property and casualty reinsurers), investments, or financial management. MR. SAMUEL H. COX: I'm from Georgia State University. This session is on securifiza- tion of insurance risk. Hans Biihlmann is the main instructor for this teaching session. Hans will give a presentation on some ideas about securifization of insurance risk. In the second period I'll give some specific examples from the Chicago Board of Trade's insur- ance futures and options. A third period will allow for discussion. Hans is visiting us from the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, where he is a professor of mathematics. He is also former president of the Institute and former dean of faculty. He serves on the board of Swiss Re and is involved in a number of other activities in the actuarial profession in Europe. With that brief introduction, I'll turn it over to Professor Bfihlmarm. MR. HANS BIJHLMANN: A symposium will beheld next week at Georgia State University. It is about alternative risk transfers, alternative in the sense that, until now, risk transfers in insurance have typically been done through the channel of reinsurance. -

IDEX IRS Products

IDEX IRS Products International Derivatives Clearing Group (IDCG), a majority owned, independently operated subsidiary of The NASDAQ OMX Group®, has developed an integrated derivatives trading and clearing platform. This platform will provide an efficient and transparent venue to trade, clear and settle IDEXTM interest rate swap (IRS) futures as well as other fixed income derivatives contracts. The platform offers a state-of-the-art trade matching engine and a best-in-breed clearing system through IDCG’s wholly-owned subsidiary, the International Derivatives Clearinghouse, LLC (IDCH)*. The trade matching engine is provided by IDCG and operated under the auspices of the NASDAQ OMX Futures Exchange (NFX), a wholly- owned subsidiary of The NASDAQ OMX Group, in NFX’s capacity as a CFTC-designated contract market for IDEXTM IRS futures products. IDEXTM IRS Product Offerings IDEXTM IRS futures are designed to be economically equivalent in every material respect to plain vanilla interest rate swap contracts currently traded in the OTC derivatives market. The first product launched was IDEXTM USD Interest Rate Swap Futures. • IDEXTM USD Interest Rate Swap Futures — The exchange of semi-annual fixed-rate payments in exchange for quarterly floating-rate payments based on the 3-Month U.S. Dollar London Interbank Offered Rate (USD LIBOR). There are thirty years of daily maturities available for trading on days that NFX and IDCH are open for business. • IDEX SwapDrop PortalTM — The SwapDrop Portal is a web portal maintained by the NFX, which is utilized to report Exchange of Futures for Swaps (EFS) transactions involving IDEXTM USD Interest Rate Swap Futures contracts. -

Interest Rate Models: Paradigm Shifts in Recent Years

Interest Rate Models: Paradigm shifts in recent years Damiano Brigo Q-SCI, Managing Director and Global Head DerivativeFitch, 101 Finsbury Pavement, London Columbia University Seminar, New York, November 5, 2007 This presentation is based on the book "Interest Rate Models: Theory and Practice - with Smile, Inflation and Credit" by D. Brigo and F. Mercurio, Springer-Verlag, 2001 (2nd ed. 2006) http://www.damianobrigo.it/book.html Damiano Brigo, Q-SCI, DerivativeFitch, London Columbia University Seminar, November 5, 2007 Overview ² No arbitrage and derivatives pricing. ² Modeling suggested by no-arbitrage discounting. 1977: Endogenous short-rate term structure models ² Reproducing the initial market interest-rate curve exactly. 1990: Exogenous short rate models ² A general framework for no-arbitrage rates dynamics. 1990: HJM - modeling instantaneous forward rates ² Moving closer to the market and consistency with market formulas 1997: Fwd market-rates models calibration and diagnostics power ² 2002: Volatility smile extensions of Forward market-rates models Interest rate models: Paradigms shifts in recent years 1 Damiano Brigo, Q-SCI, DerivativeFitch, London Columbia University Seminar, November 5, 2007 No arbitrage and Risk neutral valuation Recall shortly the risk-neutral valuation paradigm of Harrison and Pliska's (1983), characterizing no-arbitrage theory: A future stochastic payo®, built on an underlying fundamental ¯nancial asset, paid at a future time T and satisfying some technical conditions, has as unique price at current time t -

The Role of Interest Rate Swaps in Corporate Finance

The Role of Interest Rate Swaps in Corporate Finance Anatoli Kuprianov n interest rate swap is a contractual agreement between two parties to exchange a series of interest rate payments without exchanging the A underlying debt. The interest rate swap represents one example of a general category of financial instruments known as derivative instruments. In the most general terms, a derivative instrument is an agreement whose value derives from some underlying market return, market price, or price index. The rapid growth of the market for swaps and other derivatives in re- cent years has spurred considerable controversy over the economic rationale for these instruments. Many observers have expressed alarm over the growth and size of the market, arguing that interest rate swaps and other derivative instruments threaten the stability of financial markets. Recently, such fears have led both legislators and bank regulators to consider measures to curb the growth of the market. Several legislators have begun to promote initiatives to create an entirely new regulatory agency to supervise derivatives trading activity. Underlying these initiatives is the premise that derivative instruments increase aggregate risk in the economy, either by encouraging speculation or by burdening firms with risks that management does not understand fully and is incapable of controlling.1 To be certain, much of this criticism is aimed at many of the more exotic derivative instruments that have begun to appear recently. Nevertheless, it is difficult, if not impossible, to appreciate the economic role of these more exotic instruments without an understanding of the role of the interest rate swap, the most basic of the new generation of financial derivatives. -

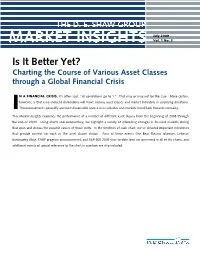

Is It Better Yet? Charting the Course of Various Asset Classes Through a Global Financial Crisis

July 2009 Vol. 1 No. 3 Is It Better Yet? Charting the Course of Various Asset Classes through a Global Financial Crisis N A FINANCIAL CRISIS, it’s often said, “all correlations go to 1.” That may or may not be the case. More certain, however, is that crisis-induced dislocations will move various asset classes and market indicators in surprising directions. I Those movements generally are most discernable once a crisis subsides and markets trend back towards normalcy. This Market Insights examines the performance of a number of different asset classes from the beginning of 2008 through the end of 2Q09. Using charts and commentary, we highlight a variety of interesting changes in financial markets during that span and discuss the possible causes of those shifts. In the timelines of each chart, we’ve denoted important milestones that provide context for each of the asset classes shown. Four of these events (the Bear Stearns takeover, Lehman bankruptcy filing, TARP program announcement, and S&P 500 2009 year-to-date low) are presented in all of the charts, and additional events of special relevance to the chart in question are also included. Is It Better Yet? Exhibit 1. U.S. High-Yield Credit Outperforms U.S. Large Cap Stocks 1 2 3 4 1.2 U.S. Fiscal Stimulus 1.0 0.8 0.6 1 Bear Stearns takeover BAC purchase 2 Lehman filing 0.4 of Countrywide 3 TARP announcement Normalized Total Return 4 S&P 500 2009 low Madoff 0.2 0.0 1Q08 2Q08 3Q08 4Q08 1Q09 2Q09 S&P 500 Barclays Capital U.S.