Final Report of the Workplace Harassment Commission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

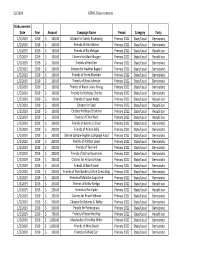

Astrazeneca's PAC Contributions Report: First

Q1 2019 AZPAC Disbursements Disbursement Date Year Amount Campaign Name Period Category Party 1/2/2019 2019$ 100.00 Citizens for Sandy Rosenberg Primary 2022 State/Local Democratic 1/2/2019 2019$ 100.00 Friends of Erek Barron Primary 2022 State/Local Democratic 1/2/2019 2019$ 100.00 Friends of Ric Metzgar Primary 2022 State/Local Republican 1/2/2019 2019$ 100.00 Citizens for Matt Morgan Primary 2022 State/Local Republican 1/2/2019 2019$ 100.00 Friends of Ken Kerr Primary 2022 State/Local Democratic 1/2/2019 2019$ 100.00 Citizens for Heather Bagnall Primary 2022 State/Local Democratic 1/2/2019 2019$ 100.00 Friends of Harry Bhandari Primary 2022 State/Local Democratic 1/2/2019 2019$ 100.00 Friends of Steve Johnson Primary 2022 State/Local Democratic 1/2/2019 2019$ 100.00 Friends of Karen Lewis Young Primary 2022 State/Local Democratic 1/2/2019 2019$ 100.00 Friends for Nicholas Charles Primary 2022 State/Local Democratic 1/2/2019 2019$ 100.00 Friends of Susan Krebs Primary 2022 State/Local Republican 1/2/2019 2019$ 100.00 Citizens for Saab Primary 2022 State/Local Republican 1/2/2019 2019$ 100.00 Citizens for Brian Chisholm Primary 2022 State/Local Republican 1/2/2019 2019$ 150.00 Friends of Chris West Primary 2022 State/Local Republican 1/2/2019 2019$ 200.00 Friends of Bonnie Cullison Primary 2022 State/Local Democratic 1/2/2019 2019$ 200.00 Friends of Ariana Kelly Primary 2022 State/Local Democratic 1/2/2019 2019$ 200.00 Sheree Sample‐Hughes Campaign Fund Primary 2022 State/Local Democratic 1/2/2019 2019$ 200.00 Friends of Robbyn Lewis -

2014 Political Corporate Contributions 2-19-2015.Xlsx

2014 POLITICAL CORPORATE CONTRIBUTIONS Last Name First Name Committee Name State Office District Party 2014 Total ($) Alabama 2014 PAC AL Republican 10,000 Free Enterprise PAC AL 10,000 Mainstream PAC AL 10,000 Collins Charles Charlie Collins Campaign Committee AR Representative AR084 Republican 750 Collins‐Smith Linda Linda Collins‐Smith Campaign Committee AR Senator AR019 Democratic 1,050 Davis Andy Andy Davis Campaign Committee AR Representative AR031 Republican 750 Dotson Jim Jim Dotson Campaign Committee AR Representative AR093 Republican 750 Griffin Tim Tim Griffin Campaign Committee AR Lt. Governor AR Republican 2,000 Rapert Jason Jason Rapert Campaign Committee AR Senator AR035 Republican 1,000 Rutledge Leslie Leslie Rutledge Campaign Committee AR Attorney General AR Republican 2,000 Sorvillo Jim Jim Sorvillo Campaign Committee AR Representative AR032 Republican 750 Williams Eddie Joe GoEddieJoePAC AR Senator AR029 Republican 5,000 Growing Arkansas AR Republican 5,000 Senate Victory PAC AZ Republican 2,500 Building Arizona's Future AZ Democratic 5,000 House Victory PAC AZ Republican 2,500 Allen Travis Re‐Elect Travis Allen for Assembly 2014 CA Representative CA072 Republican 1,500 Anderson Joel Tax Fighters for Joel Anderson, Senate 2014 CA Senator CA038 Republican 2,500 Berryhill Tom Tom Berryhill for Senate 2014 CA Senator CA008 Republican 2,500 Bigelow Frank Friends of Frank Bigelow for Assembly 2014 CA Representative CA005 Republican 2,500 Bonin Mike Mike Bonin for City Council 2013 Officeholder Account CA LA City Council -

Baltimore City Redistricting Reform Commission Meeting University of Baltimore Law School 1401 N

Baltimore City Redistricting Reform Commission Meeting University of Baltimore Law School 1401 N. Charles St., Baltimore, MD 21201 Judge Alex Williams - Calls meeting to order at 1:11pm Judge Alex Williams - Welcomes everyone to Baltimore. I am the co – chair, we are here to hear from the public and stakeholder organizations. We have been at this two years now. The Commission was appointed by Governor Hogan. Gerrymandering is an issue haunting Maryland. Both congressional and legislative districts are drawn in an unfair manner. We have members of the commission joining us here today. Governor Hogan appointed seven members to the Commission of whom three are Democrats, three are Republicans and one is not affiliated with a political party. The Governor selected Walter Olson, a Republican from Frederick County and Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute, and myself, a Democrat from Prince George’s County and former U.S. District Court Judge, to serve as co-chairmen of the Commission. Additional members appointed by the Governor include Tessa Hill-Aston, President of the Baltimore City branch of the NAACP, Michael Goff, who is the President of the Northeast-Midwest Institute and a board member at Common Cause Maryland. Christopher Summers, who is President of the Maryland Public Policy Institute. Carol Ramirez, a Bethesda resident and small business owner, and Ashley Oleson, Administrator for the League of Women Voters of Maryland were also added to the commission by Governor Hogan. President of the Maryland Senate Thomas V. Mike Miller, Jr. appointed Senator Joan Carter Conway who represents District 43 in Baltimore City and serves as Chair of the Education, Health and Environmental Affairs Committee. -

Scorecard 2011-2014 2

Report on th e MARYLAND GENERAL ASSEMBLY SCORECARD 2011-2014 2 2012 2014 2011-2014 Maryland Legislation SB 317 & HB 131 – Retail Pet Stores SB 827 & HB 1124 – Roadside Zoos Requires retail pet stores to disclose information Establishes basic animal welfare and public safety SCORED BY about the puppies they sell and establishes requirements for facilities keeping big cats, bears Humane Society Legislative Fund remedies for consumers who purchase sick puppies and primates. from pet stores. Signed into Law. Sponsored by Senator Catherine & Maryland Votes For Animals Signed into Law. Sponsored by Senator Catherine Pugh and Delegate Eric Luedtke Pugh and Delegate Nic Kipke SB 659 & HB 665 – Surgical Procedures on Dogs SB 465 & HB 393 – Shark Fins 2011 Prohibits ear cropping, tail docking, dewclaw Bans the possession, distribution and sale of shark fins. removal and surgical births of dogs, unless done by SB 115 & HB 227 – Animal Cruelty Passed the Senate. Sponsored by Senator Brian a veterinarian under anesthesia. Authorizes a court to prohibit someone convicted Frosh and Delegate Eric Luedtke Signed into Law. Sponsored by Senator Lisa of animal cruelty from owning an animal as a Gladden and Delegate Ben Kramer condition of probation. SB 203 & HB 484 – Cost of Care SB 660 & HB 667 – Devocalization Signed into law. Sponsored by Senator Jim Robey Authorizes a court to require someone convicted of and Delegate Jeff Waldstreicher animal cruelty to pay for the costs of caring for the Prohibits devocalization of dogs and cats unless animals during the course of the trial. medically necessary. SB 747 & HB 407 – Pet Protective Orders Passed the Senate. -

2014 Report of Political Financial Support

2014 2014 Lilly Political Contributions As a biopharmaceutical company that treats serious diseases, Lilly plays an important role in public health and its related policy debates. It is important that our company shapes global public policy debates on issues specific to the people we serve and to our other key stakeholders including shareholders and employees. Our engagement in the political arena helps address the most pressing issues related to ensuring that patients have access to needed medications—leading to improved patient outcomes. Through public policy engagement, we provide a way for all of our locations globally to shape the public policy environment in a manner that supports access to innovative medicines. We engage on issues specific to local business environments (corporate tax, for example). Based on our company’s strategy and the most recent trends in the policy environment, our company has decided to focus on three key areas: innovation, health care delivery, and pricing and reimbursement. More detailed information on key issues can be found in our 2014 Corporate Responsibility Update. Through our policy research, development, and stakeholder dialogue activities, Lilly develops positions and advocates on these issues. Government actions such as price controls, pharmaceutical manufacturer rebates, and access to Lilly medicines affect our ability to invest in innovation. Lilly has a comprehen- sive government relations operation to have a voice in the public policymaking process at the federal, state, and local levels. Lilly is committed to participating in the political process as a responsible corporate citizen to help inform the U.S. debate over health care and pharmaceutical innovation. -

DRAFT ---APTA Maryland – Key Legislators

2020 PAC Contribution Budget: $4,000 DRAFT ---- APTA Maryland – Key Legislators Current Donations: $3,600 (As of October 15, 2020) Given Suggested Current Cycle Title First Name Last Name District Committee Amount (1/1/2019 Upcoming Event(s): Campaign Info 2020 thru 12/31/2022) Color Code Key: Influential Leaders: highlighted yellow; FIN Health Subcommittee members: green; EHEA Health Subcommittee members: orange ; HGO Health Occupations Subcommittee members: red; HGO Insurance Subcommittee members: blue; Senate and House Leaders: pink Citizens for Bill Ferguson C/o Martin Lauer Associates 1215 E. Fort Avenue, Suite 106 Senate Pres Bill Ferguson D Baltimore, MD 21230 President 410-547-8884 [email protected] billforbaltimore.com/november7 District 3 Friends of Ron Young Sen. Ron Young D Frederick Senate $200 P.O. Box 724 County Frederick, MD 21705 Citizens for Delores Kelley FIN – Chair District 10 c/o Rice Consulting Subcom Sen. Delores Kelley D Baltimore $100 17 W. Courtland Street Chair, County Suite 210 Health Bel Air, MD 21014 Citizens for Brian Feldman District 15 FIN - Vice PO Box 34408 Sen. Brian Feldman D Montgomery $100 Ch Bethesda, MD 20827, MD 20827 County 301-517-5719 November 10, 2020; Friends of Malcolm Augustine District 47 7:00pm-8:00pm PO Box 272 Sen. Malcolm Augustine D Prince George's FIN Virtual Fundraiser Bladensburg, MD 20710 County $47, $100, $250, $500, 301-383-8011 $1,000, $2,500 www.malcolmaugustine.com Page 1 of 11 2020 PAC Contribution Budget: $4,000 Current Donations: $3,600 Given Suggested Current Cycle Title First Name Last Name District Committee Amount (1/1/2019 Upcoming Event(s): Campaign Info 2020 thru 12/31/2022) Color Code Key: Influential Leaders: highlighted yellow; FIN Health Subcommittee members: green; EHEA Health Subcommittee members: orange ; HGO Health Occupations Subcommittee members: red; HGO Insurance Subcommittee members: blue; Senate and House Leaders: pink www.malcolmaugusti ne.com/augustine11_ 10 Friends of Pam Beidle c/o Rice Consulting, 17 W Courtland District 32 St., Suite 210 Sen. -

February 16, 2020 the Honorable Maggie Mcintosh, Chairman House

February 16, 2020 The Honorable Maggie McIntosh, Chairman House Appropriations Committee 6 Bladen Street, Suite 121 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 The Honorable Anne Kaiser, Chairman House Ways and Means Committee 6 Bladen Street, Suite 131 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 Dear Madame Chairs, As you are aware, at Noon tomorrow, February 7, 2012, four committees in the General Assembly will hold a joint hearing on HB 1300/SB 1000 – Blueprint for Maryland’s Future – Implementation. This is one of the most significant pieces of legislation the Maryland General Assembly has considered in a generation; not only because of the fundamental changes it is said to make in our education system but also for the tremendous price tag that it carries. For better or for worse, this legislation will have a staggering impact on Maryland for years to come. It is our duty, as the elected representatives who will consider and ultimately vote on this monumental piece of legislation, to do so thoughtfully and carefully. It is critical that this legislation is thoroughly vetted and analyzed, and that we hear from all parties who will be impacted by this legislation. It is just as critical that we, and the public, have access to all of the information and analysis available. It is with an abundance of concern that, at this juncture, this legislation appears to be moving forward at a rushed pace, that we write to you today. As we write this letter, the hearing for this bill is less than 24 hours away. And yet, after more than three years of meetings, decisions, and recommendations from the Kirwan Commission and months of planning and analysis by the Department of Legislative Services, there is no Fiscal Note available; neither to the members sitting on the Committees nor to the public. -

2020 Legislative Wrap-Up

2020 Legislative Wrap-Up To Our Valued Clients, Friends, and Colleagues: The 440th Legislative Session of the Maryland General Assembly adjourned on March 18, 2020 – 19 days earlier than expected due to the Covid-19 pandemic. After difficult deliberation and the closure of other branches of government, the presiding officers made the decision to adjourn early for the first time since the Civil War. Due to emergency precautions in the last days of the Legislative Session, all state buildings, including the State House and all legislative offices, were closed to the general public and access to legislators was substantially curtailed. The General Assembly focused on fulfilling their constitutional duty to pass a balanced budget and some other key pieces of legislation, including the highly anticipated Blueprint for Maryland’s Future. At this time each year, HJM likes to take a moment to share the highlights of the Legislative Session. Despite the early adjournment, the 2020 session was extremely busy with members of the Maryland General Assembly introducing 2,745 bills, excluding local bond initiatives and 18 Joint Resolutions. The following synopsis is not an exhaustive report of the legislative activities this session, but an overview of particular topics of interest. If you have specific questions, please feel free to contact us. Please note that the table of contents in this document is interactive. If you would like to jump to a specific topic or issue, just click that issue in the table of contents. Thank you for entrusting your legal, lobbying and government relations needs in the State of Maryland with Harris Jones & Malone, LLC. -

OVERDOSED on Opioids

ETHICAL DILEMMAS: WHAT DO YOU DO WHEN THE LAW IS SILENT? PAGE 24 April 2016 OVERDOSED ON Opioids Teen Pregnancy • Student Data • Retirement Savings I’m developing innovative technology that recycles nuclear fuel to generate electricity. With nuclear energy, we can have both reliable electricity and clean air. Leslie Dewan, Technology Innovator, Forbes 30 Under 30 Can We Reduce CO2 Without NUCLEAR ENERGY? The world has set ambitious clean air goals and American innovators, like Leslie Dewan, Bill Gates and Jose Reyes, are developing advanced nuclear energy technologies to reduce carbon emissions. Nuclear energy produces 63% of America’s carbon-free electricity and they know it has a distinct role to play to meet future energy and clean air goals. LEARN MORE nei.org/whynuclear Nuclear. Clean Air Energy. #WhyNuclear CLIENT: NEI (Nuclear Energy Institute) PUB: State Legislatures Magazine RUN DATE: March SIZE: 7.5” x 9.875” Full Page VER.: Leslie - FP Ad 4CP: APRIL 2016 VOL. 42 NO. 4 | CONTENTS A National Conference of State Legislatures Publication www.ncsl.org/magazine Executive Director William T. Pound Director of Communications NCSL’s national magazine of policy and politics Karen Hansen Editor Julie Lays FEATURES DEPARTMENTS Assistant Editor Kevin Frazzini Contributing Editor Overdosed on Opioids Page 9 IN MEMORIAM PAGE 4 Jane Carroll Andrade BY JANE HOBACK Nevada Senator Debbie Smith, former NCSL president Advertising Sales Manager A deadly opioid epidemic sweeping the country has LeAnn Hoff (303) 364-7700 lawmakers working hard to find solutions. SHORT TAKES PAGE 5 [email protected] Connections, support, expertise and ideas from NCSL Contributors Max Behlke Brenda Erickson Doug Farquhar TRENDS PAGE 6 Karmen Hanson Heather Morton Rethinking the use of solitary confinement for juveniles, Molly Ramsdell Wendy Underhill moving forward with remote sales tax legislation, looking Amber Widgery for the state that best represents the U.S. -

2016 U.S. Political Contributions & Related Activity Report

U.S. Political Contributions 2016 & Related Activity Report Letter from the Chairman Our workforce of more than 240,000 people is dedicated to helping people live healthier lives and helping to make the health system work better for everyone. As federal and state policy-makers, on behalf of their constituents and communities, continue to advance solutions to reform the health care marketplace, UnitedHealth Group remains an active participant in the political process to provide proven solutions that improve the health care system. The United for Health PAC is an important part of our overall strategy to engage with elected officials and policy-makers to communicate our perspectives on priority issues and to share with them our capabilities and innovations. The United for Health PAC is a nonpartisan political action committee supported by voluntary contributions from eligible employees. The PAC supports federal and state candidates who champion policies that increase quality, access and affordability in health care in accordance with applicable election laws and as overseen by the UnitedHealth Group Board of Directors’ Public Policy Strategies and Responsibility Committee. UnitedHealth Group is committed to sharing with federal and state policy-makers our solutions to create a modern, high-performing, simpler health care system. Steve Heyman United for Health PAC Chairman Senior Vice President & Head of UHG Government Affairs Political Contributions and Related Activity UnitedHealth Group’s mission is to help people live healthier lives and to help the health care system work better for everyone. UnitedHealth Group engages in efforts to shape and inform public policy decisions that have the potential to impact the quality and delivery of health care that affect our customers, employees, consumers, and the communities in which we operate. -

2019 YE IRW Report

2019 Political Contributions Name Candidate Office Amount ALABAMA Terri Sewell For Congress Rep. Terri Andrea Sewell (D) U.S. House of Representatives $ 2,000 Johnson & Johnson Political Action Committee Doug Jones For Senate Committee Sen. Doug Jones (D) U.S. Senate $ 2,500 Johnson & Johnson Political Action Committee Alabama House Republican Conference, Inc. $ 1,000 Johnson & Johnson Political Action Committee MACC PAC/Alabama $ 1,000 Johnson & Johnson Political Action Committee ARKANSAS Boozman For Arkansas Sen. John Nichols Boozman (R) U.S. Senate $ 3,500 Johnson & Johnson Political Action Committee ARIZONA Sinema For Arizona Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (D) U.S. Senate $ 2,000 Johnson & Johnson Political Action Committee McSally For Senate Inc Sen. Martha Elizabeth McSally (R) U.S. Senate $ 1,000 Johnson & Johnson Political Action Committee Arizona Democratic Party Political Action Committee $ 5,000 Johnson & Johnson Political Action Committee Arizona Republican Party Arizona Republican Party Political Action Committee $ 5,000 Johnson & Johnson Political Action Committee CALIFORNIA Anna Eshoo For Congress Rep. Anna G. Eshoo (D) U.S. House of Representatives $ 1,000 Johnson & Johnson Political Action Committee Barragan For Congress Rep. Nanette Diaz Barragan (D) U.S. House of Representatives $ 2,500 Johnson & Johnson Political Action Committee Devin Nunes Campaign Committee Rep. Devin G. Nunes (R) U.S. House of Representatives $ 2,500 Johnson & Johnson Political Action Committee Dr. Raul Ruiz For Congress Rep. Raul Ruiz (D) U.S. House of Representatives $ 2,000 Johnson & Johnson Political Action Committee Kevin McCarthy For Congress Rep. Kevin Owen McCarthy (R) U.S. House of Representatives $ 10,000 Johnson & Johnson Political Action Committee Lou Correa For Congress Rep. -

Talented CSP Junior Benjamin Kelm: an Incredible Lesson in Political Science

Talented CSP Junior Benjamin Kelm: An Incredible Lesson in Political Science March 2016 Chesapeake Science Point 11th grade student, Benjamin Kelm, learns some incredible lessons into the inside workings of a very important political issue: the gerrymandering of Maryland Congressional districts. These workings include Ben having the opportunity to discuss his work in depth with the Maryland House of Delegates Minority Leader, Delegate Nicholas Kipke, being honored by Delegate Kipke in the Maryland House of Delegates, the opportunity to provide testimony in the Maryland Senate and the ability to meet and discuss the issue with state leaders. Last summer, Maryland Governor Larry Hogan formed a commission to study potentially reforming the creation of Maryland’s Congressional districts. Gerrymandering is the act of one political party drawing extremely biased and convoluted district borders to maximize their political advantage. When Benjamin Kelm learned about the Governor’s initiative, he selected it for his 11th grade science fair project; to research mathematical algorithmic approaches to creating unbiased districts. Ben successfully developed a C++ program implementing his algorithm that could create unbiased Congressional districts, using 2010 Census data as its input. Even though he completed his science fair research at nearly the same time that the Maryland Redistricting Reform Commission published their final results, Ben was very pleased to see that his findings were well aligned with the Governor’s Commission. After presenting his project to judges at the Chesapeake Science Point and earning a spot in the Chesapeake Lighthouse Foundation Science Fair Finals in December 2015, Ben was thrilled to learn that he won the First Place Grand Award for his project at the February 2016 CLF STEM Fair Dinner & Awards Ceremony.