Excavations at Al-Khor Island, Qatar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE QATAR GEOLOGIC MAPPING PROJECT Randall C

LINKING GEOLOGY AND GEOTECHNICAL ENGINEERING IN KARST: THE QATAR GEOLOGIC MAPPING PROJECT Randall C. Orndorff U.S. Geological Survey, 12201 Sunrise Valley Drive, Reston, Virginia, 20192, USA, [email protected] Michael A. Knight Gannett Fleming, Inc., P.O. Box 67100, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, 17106, USA, [email protected] Joseph T. Krupansky Gannett Fleming, Inc., 1010 Adams Avenue, Audubon, Pennsylvania, 19403, USA, [email protected] Khaled M. Al-Akhras Ministry of Municipality and Environment, Doha, Qatar, [email protected] Robert G. Stamm U.S. Geological Survey, 12201 Sunrise Valley Drive, Reston, Virginia, 20192, USA, [email protected] Umi Salmah Abdul Samad Ministry of Municipality and Environment, Doha, Qatar, [email protected] Elalim Ahmed Ministry of Municipality and Environment, Doha, Qatar, [email protected] Abstract During a time of expanding population and aging urban Introduction infrastructure, it is critical to have accurate geotechnical Currently, the State of Qatar does not have adequate and geological information to enable adequate design geologic maps at regional and local scales with detailed and make appropriate provisions for construction. This descriptions, proper base maps, GIS, and digital geoda- is especially important in karst terrains that are prone to tabases to adequately support future development. To sinkhole hazards and groundwater quantity and quality better understand the region’s geological and geotech- issues. The State of Qatar in the Middle East, a country nical conditions influencing long term sustainability of underlain by carbonate and evaporite rocks and having future development, the Infrastructure Planning Depart- abundant karst features, has recognized the significance ment (IPD) of the Ministry of Municipality and Environ- of reliable and accurate geological and geotechnical ment (MME) of the State of Qatar has commenced the information and has undertaken a project to develop a Qatar Geologic Mapping Project (QGMP). -

Annual Report 2016

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 CONTENTS 3 - 8 BOARD OF DIRECTORS 9 - 10 BOARD OF DIRECTORS REPORT 11 SHARI’A SUPVERVISORY BOARD REPORT 13 - 14 MESSAGE FROM THE GROUP CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER 15 - 16 FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS 17 - 18 COMPANY VISION AND STRATEGY 19 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 21 BARWA REAL ESTATE GROUP 23 - 34 REAL ESTATE PROJECTS IN QATAR 35-36 AL AQARIA REAL ESTATE PROJECTS 37 - 38 INTERNATIONAL INVESTMENTS 39 INDEPENDENT SUBSIDIARIES 40 HELPING PEOPLE FIND THEIR DREAMS 41-42 COMMITMENT TO COMMUNITY 43 OUR EMPLOYEES 1 H.H. SHEIKH TAMIM BIN HAMAD AL THANI THE EMIR OF THE STATE OF QATAR 2 H.H. SHEIKH HAMAD BIN KHALIFA AL THANI THE FATHER EMIR 3 BOARD OF DIRECTORS HIS EXCELLENCY MR. SALAH BIN GHANEM BIN NASSER AL ALI CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS H.E. Mr. Salah Bin Ghanem Bin was appointed as a consultant in the Nasser Al Ali was appointed as Qatar’s office of the Heir Apparent till 2013. Minister of Sports and Culture on He was also appointed as the General January 27th, 2016 after more than Manager of the Sheikh Jasim Bin two years as Minister of Youth and Mahmoud Bin Thani Foundation Sports. His Excellency held a number for Social Care; a private institute of public positions such as Chief of for public interest established by the State Audit Bureau between His Highness The Father Emir 2006 and 2011, during which Sheikh Hamad Bin Khalifa Al H.E participated in developing a Thani. In 2012, H.E. participated in strategic plan for the Bureau aimed the launch of Al Rayyan TV with a at assisting in achieving sustainable mission to support the renaissance development for the Qatari society of Qatar, consolidate its national and to strengthen accountability. -

All Qatar Residents to Get Covid Vaccine Free

INDEX QATAR 2-6,12 COMMENT 10 BUSINESS | Page 1 QATAR | Page 12 ARAB WORLD 7 BUSINESS 1-12 Qatar private INTERNATIONAL 7-9,11 SPORTS 1-8 Last Covid-19 sector bounces DOW JONES QE NYMEX patient back on lift ing discharged 28,148.64 9,956.66 39.36 of Covid-19 +465.83 +3.15 +2.31 from Lebsear +1.68% +0.03% +6.23% curbs: QFC Latest Figures Field Hospital published in QATAR since 1978 TUESDAY Vol. XXXXI No. 11693 October 6, 2020 Safar 19, 1442 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals PM offers condolences to Amir of Kuwait HE the Prime Minister and Minister of Interior Sheikh Khalid bin Khalifa bin Abdulaziz al-Thani yesterday off ered condolences to the Amir of Kuwait, Sheikh Nawaf al-Ahmad al-Jaber al-Sabah, on the death of Sheikh Sabah al-Ahmad al-Jaber al-Sabah, praying to Allah to have mercy on the soul of the deceased and to rest it in peace in Paradise. The prime minister also off ered condolences to members of the ruling family and ranking off icials. Ministers and members of the off icial delegation accompanying the prime minister also off ered their condolences. Two held for violating PM meets Afghan president home quarantine rules Competent authorities arrested yesterday two people who violated All Qatar residents to the requirements of the home quarantine, which they committed to following, in accordance with the procedures of the health authorities in the country. The get Covid vaccine free two persons being referred to prosecution are: Albert Mondano Oshavillo and Nasser Ghaidan By Ayman Adly is not yet clear whether the upcoming Mohamed al-Hatheeth al-Qahtani. -

Cool Waterfronts and Coastal Cities: How Qatar’S Peninsula Develops a Resilient Future?

Alraouf, Ali & Al Nuaimi, Mubarak Cool Waterfronts in Qatar 54th ISOCARP Congress 2018 Cool Waterfronts and Coastal Cities: How Qatar’s Peninsula Develops a Resilient Future? Ali A. Alraouf, Ph.D. Mubarak Al Nuaimi, BSc., MA. Eng. Prof. of Architecture and Urbanism Advisor of Urban Planning Affairs Head of CB, Training & Development at Head of Central Doha Project QNMP - MME QNMP - MME Doha, Qatar Doha, Qatar [email protected] [email protected] Abstract The coast is one of the most complex systems on earth as it is the result of the continuous interaction between people, land and water. These physical processes shape the geomorphology of the coast, which sustains specific ecosystems that provide crucial services to human societies to flourish. This paper aims at expanding the understanding on the functioning of the waterfronts, which are crucial factor to increase the awareness regarding the challenges of developing and governing coastal areas and waterfronts. Evidently, climate change represents the major human-induced source of natural risks. Understanding the risks associated to the coast is crucial to provide safe and resilient human environment. Planners must address the challenges of waterfronts and coastal areas’ planning approaches. Coastal cities are facing the challenge not only by providing high quality services for its inhabitants but also to integrate specific coastal and waterfront uses that demand a large quantity of space and requires highly specialized services. Ports, dwellings, beaches, promenades, protectorates, industry, logistics, resorts, restaurants, are just few of the uses that characterized most coastal cities and waterfronts and need to be integrated into the urban fabric and smartly diminish the consequences of climate change. -

Flu Vaccine Safe and Need of the Hour

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 Al Khaliji Al Naama scores net pips Gtnah profi t of in Umm Bab QR544mn Cup thriller published in QATAR since 1978 FRIDAY Vol. XXXXI No. 11710 October 23, 2020 Rabia I 6, 1442 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals In brief PM visits S’hail 2020 exhibition Flu vaccine Infantino rules out holding Qatar World Cup without fans FIFA President Gianni Infantino safe and need yesterday ruled out hosting the 2022 World Cup in Qatar without fans. The competition will take place in winter for the first time-ever from November 21 to December 18. Infantino told journalists of the hour: in Zurich that there will be enough time by the end of 2022 to contain the coronavirus pandemic. He noted that while the health crisis represents a threat to football now, it should be top offi cial contained by the time the World Cup arrives. he fl u virus can cause severe “We have also begun offering the Registration for illness for some people, espe- vaccine to the public, and especially winter camping Tcially those at increased risk to those aged 50 years or above, for developing infl uenza-related children from six months to five reopens on Sunday complications, Dr Abdullatif al-Khal, years of age, people with chronic The Ministry of Municipality and head of the Infectious Diseases Divi- diseases, and pregnant women at Environment (MME) has announced sion at Hamad Medical Corporation all stages of pregnancy,” Dr al-Khal that it will reopen registration for (HMC), cautioned yesterday. -

Page 01 Jan 23.Indd

3rd Best News Website in the Middle East BUSINESS | 17 SPORT | 25 Lulu Group AFC U-23 semi-final: partners with World Qatar raring to go Economic Forum against Vietnam Tuesday 23 January 2018 | 6 Jumada 1 | 1439 www.thepeninsula.qa Volume 22 | Number 7415 | 2 Riyals Get inclusive with the new Fibre Plans! Qatar-EU air & Emir meets GECF Secretary-General Qatar’s AG meets FBI sea freight lane Director, US Senator to grow faster QNA SATISH KANADY The EU-Qatar air WASHINGTON: Attorney THE PENINSULA freight lane is General of the State of Qatar, H E Dr. Ali bin Fetais Al Marri, DOHA: The Qatar-EU trade forecast to grow who is currently on his lane has been projected as one by 39.4%, while official visit to Washington, of the busiest routes, both in Qatar-EU sea freight met with the Director of US terms of air and sea freight air lane is projected Federal Bureau of Investi- lanes, in the Emerging Market. gation (FBI), Christopher The EU-Qatar air freight to expand by a Wray. lane is forecast to grow by 39.4 whopping 121.7 During the meeting, both percent, while Qatar-EU sea percent. the parties discussed a freight air lane is projected to number of issues pertaining expand by a whopping 121.7 to common concern on percent. which they cooperate, as The annual Emerging EU-Ukraine (+40.9 percent), well as ways of dealing with Markets Logistics Index, EU-Qatar (+39.4 percent), EU- Emir H H Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani meeting with Secretary General of Gas Exporting Countries some other issues. -

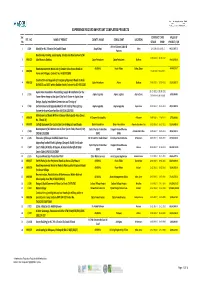

Experience Record Important Completed Projects

EXPERIENCE RECORD IMPORTANT COMPLETED PROJECTS Ser. CONTRACT DATE VALUE OF REF . NO . NAME OF PROJECT CLIENT'S NAME CONSULTANT LOCATION No STRART FINISH PROJECT / QR Artline & James Cubitt & 1 J/149 Masjid for H.E. Ghanim Bin Saad Al Saad Awqaf Dept. Dafna 12‐10‐2011/31‐10‐2012 68,527,487.70 Partners Road works, Parking, Landscaping, Shades and Development of Al‐ 22‐08‐2010 / 21‐06‐2012 2 MRJ/622 Jabel Area in Dukhan. Qatar Petroleum Qatar Petroleum Dukhan 14,428,932.00 Road Improvement Works out of Greater Doha Access Roads to ASHGHAL Road Affairs Doha, Qatar 48,045,328.17 3 MRJ/082 15‐06‐2010 / 13‐06‐2012 Farms and Villages, Contract No. IA 09/10 C89G Construction and Upgrade of Emergency/Approach Roads to Arab 4 MRJ/619 Qatar Petroleum Atkins Dukhan 27‐06‐2010 / 10‐07‐2012 23,583,833.70 D,FNGLCS and JDGS within Dukhan Fields,Contract No.GC‐09112200 Aspire Zone Foundation Dismantling, Supply & Installation for the 01‐01‐2011 / 30‐06‐2011 5 J / 151 Aspire Logistics Aspire Logistics Aspire Zone 6,550,000.00 Tower Flame Image at the Sport City Torch Tower in Aspire Zone Extension to be issued Design, Supply, Installation.Commission and Testing of 6 J / 155 Enchancement and Upgrade Work for the Field of Play Lighting Aspire Logestics Aspire Logestics Aspire Zone 01‐07‐2011 / 25‐11‐2011 28,832,000.00 System for Aspire Zone Facilities (AF/C/AL 1267/10) Maintenance of Roads Within Al Daayen Municipality Area (Zones 7 MRJ/078 Al Daayen Municipality Al Daayen 19‐08‐2009 / 11‐04‐2011 3,799,000.00 No. -

Medical Booklet

Al Khor Community Medical Centre Medical Book TABLE OF CONTENTS MessageM from the Chief Employee Development & Welfare Officer 2 MessageM from the Manager (Medical Services) 3 Important contacts 4 What is Primary Health Care 6 Dependent Eligibility 8 Dental Services 10 Medical Clinic information 12 Specialty Clinic Times 16 What do I do when I arrive? 18 Immunisation clinic 19 Specialty Clinics 30 Pharmacy 31 Laboratory 32 Medical and Dental Claims 32 Authorized sick leave 33 Patients’ Bill of Rights and Responsibilities 35 Suggestions and Complaints 36 AKCMC Medical Team We hhaveave mamaded every effort to keep the information in this booklet accurate. Any changes, updates or circulars will be notified on the share point company web page which employees can access. http://portal/SitePages/Home.aspx MESSAGE From the CHIEF EMPLOYEE DEVELOPMENT & WELFARE OFFICER The continuing success of any community is dependent on the health of its residents. Al Khor Community Medical Centre (AKCMC) offers free, comprehensive medical and dental care to the community. In addition to treating employees and their families, health care indicators are monitored to development preventative strategies to maintain an active, healthy community, and a productive workforce. It has been my pleasure to witness and contribute to the development and expansion of AKCMC, the first JCI accredited Primary Healthcare facility in Qatar. AKCMC maintains bench marked standards and are committed to continuous improvement. Mr Erhama Al Kaabi As you will see in this booklet, AKCMC offers a wide range of services to meet Chief Employee Development & Welfare Officer the ever growing and changing needs of the community. -

Karwa Smartcard - Merchant Name, Area and Tel No

Karwa Smartcard - Merchant Name, Area and Tel No: 1.Doha Bus StationAl Ghanim 44366053 2.Royal Mobile (Food World)Industrial (Food World) 77339666 3.Abdulla Ali Food StuffCentral Market 44683736 4.Safari Shopping ComplexUm Salal Mohamad 44792840 5.Kabayan SupermarketSouq Asiri (Pilipino Souq) 55712164 6.Al Isma trading Co. W.L.L.Musherib St 44327360 7.Landmart HyperStreet 49 Industrial 44504400 8.Faz SupermarketStreet 36, Industrial Area 44600538 9.AL-Harabi Trading CentreAl Khor 44720542 10.Family Shopping ComplexMuaither Str 44509726 11.Farhana Studio Shahaniya 77459300 12.Danube SupermarketIndustrial Area 44606285 13.Al-Rawabi ElectronicsRayyan 77987738 14.G-Mart Mansoura 44214756 15.Safwa Super MarketMusiereb 44310224 16.Safari HypermarketAin Khalid, Salwa Road 44696196 17.Regency HypermarketAbu Hamour 44505500 18.Trendz Doha CentreAl Khor 77372171 19.Top GroceryAl Ghanim Bus station 55857990 20.Skynet Co. W.L.L.Wathana Mall (Maiether) 66562010 21.Jassela SupermarketUmn Qarn 44729513 22.Al Fida GroceryBin Omran 44873036 23.Sana GroceryBin Omran 44886364 24.Absad CaferteriaAl Ghanim Bus station 44432819 25.Foto GulfIndustrial 77475505 26.United TelecomAl Meera – Muntaza 77463007 27.Qatar Forsan ComplexSt. 33, Industrial Area 44604756 28.Skynet Food Salwa 55212365 29.Al Raya GroceryAl Laqta 44883845 30.Doha Colour studioArab Roundabout 33534474 31.Al Falah SupermarketNew Wakra 55195049 32.New Abudhabi SupermarketBin Mammoud 44431772 33.Foto GulfBarwa Village (Wakra) 44425044 34.Dubai StudioMatar Qadem 44650730 35.Al Saniya Mobile CenterAlsaad -

QATAR MONTHLY STATISTICS Edition 5 For

إﺻـﺪار ﻳﻮﻧﻴﻮ Edition of June 2014 www.mdps.gov.qa ﻗﻄــﺮ؛ إﺣﺼــﺎءات ﺷﻬــﺮﻳﺔ QATAR MONTHLY STATISTICS اﻟﻌـﺪد اﻟﺨﺎﻣﺲ- إﺣﺼـﺎءات ﻣﺎﻳﻮ ٢٠١٤ 5th Issue - Statistics of May. 2014 Al Ruwais State of Qatar Kingdom of Fuwairit Bahrain 0 5 10 20 Al Zubara Kilometers Al Shamal Al Khor and Al Thakhira Al Khor Umm Slal Al Daayen Dukhan Doha Umm Bab Al Rayyan Doha Al Wakra Mesaieed Al Wakra Settlement Abu Samra Farm Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Sawdaa Natheel اﻟﻤﺤﺘﻮﻳﺎت Contents ًأوﻻ : إﺣﺼﺎءات ﺳﻜﺎﻧﻴﺔ واﺟﺘﻤﺎﻋﻴﺔ First : Population & Social Statistics 5 ﺛﺎﻧﻴ: إﺣﺼﺎءات اﻗﺘﺼﺎدﻳﺔ Second : Economic Statistics 7 ﺛﺎﻟﺜ: إﺣﺼﺎءات ﻣﺘﻨﻮﻋﺔ Third: Miscellaneous Statistics 12 راﺑﻌ: إﺣﺼﺎءات رﺑﻌﻴﺔ Fourth: Quarterly Statistics 17 ﻧﺸﺮة "ﻗﻄﺮ؛ إﺣﺼﺎءات ﺷﻬﺮﻳﺔ" ﺗﺼﺪر ﻋﻦ وزارة اﻟﺘﺨﻄﻴﻂ اﻟﺘﻨﻤﻮي واﺣﺼﺎء ، Qatar Monthly Statistics” bulletin is released on a monthly basis by“ وﺗﺤﺘﻮى ﻋﻠﻰ ﺑﻴﺎﻧﺎت أوﻟﻴﻪ ﻋﻦ اﻟﺸﻬﺮ اﻟﻤﻨﺼﺮم ، وﺗﻮزع ﻣﺠﺎﻧ دون أدﻧﻰ .the Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics ﻣﺴﺆوﻟﻴﺔ ﻗﺎﻧﻮﻧﻴﺔ ﻧﺎﺗﺠﺔ ﻋﻦ اﺳﺘﺨﺪام اﻟﺒﻴﺎﻧﺎت اﻟﻮاردة ﻓﻴﻬﺎ. It contains the previous month’s preliminary data, distributed free of charge without any legal liability that may arise from the use of information contained therein. ﻧﺸﻜﺮ ﺟﻤﻴﻊ اﻟﻮزارات واﻟﺠﻬﺎت اﻟﺘﻲ ﺗﻌﺎوﻧﺖ ﻣﻌﻨﺎ وزودﺗﻨﺎ ﺑﺎﺣﺼﺎءات اﻟﻮاردة We thank all the ministries and stakeholders for their cooperation in ﻓﻲ ﻫﺬه اﻟﻨﺸﺮة. .providing the statistics included in the bulletin ﻳﺴﺮﻧﺎ أن ﻧﺴﺘﻘﺒﻞ أﻳﺔ ﻣﻼﺣﻈﺎت ﺗﻬﺪف إﻟﻰ ﺗﻄﻮﻳﺮ ﻫﺬه اﻟﻨﺸﺮة ًﻣﺴﺘﻘﺒﻼ :We are pleased to receive your remarks for future improvements on وذﻟﻚ ﻋﻠﻰ اﻟﺒﺮﻳﺪ اﻟﻜﺘﺮوﻧﻲ : [email protected] [email protected] ﻟﻤﺰﻳﺪ ﻣﻦ اﻟﻤﻌﻠﻮﻣﺎت واﻟﺒﻴﺎﻧﺎت ﻳﺮﺟﻰ زﻳـــﺎرة اﻟﻤﻮﻗـــﻊ اﻟﻜﺘــــﺮوﻧﻲ ﻟﻠـﻮزارة For further information and data, please visit: www.mdps.gov.qa or www.mdps.gov.qa وﻣﻮﻗﻊ (ﻗﻠﻢ) www.qalm.gov.qa www.qalm.gov.qa Number of visits to the ministry’s website in May. -

Ministers Inspect Umm Slal Quarantine Centre

BUSINESS | Page 1 QATAR | Page 3 Qatar shares bounce back on cues amid US $2tn stimulus plan Doha Bank donates QR2mn for quarantined workers published in QATAR since 1978 THURSDAY Vol. XXXXI No. 11499 March 26, 2020 Sha’ban 2, 1441 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Ministers inspect Umm Slal quarantine centre zThe compound consists of 32 buildings with a total capacity of 18,000 beds QNA the compound provides such as a clinic and for their eff orts to confront Covid-19 and Doha other facilities. to protect the society, and praised the col- The ministers were also briefed on the laboration within the community at large to response plans to receive quarantine cases follow precautionary measures to protect E the Minister of Public Health Dr according to the highest safety and security themselves, their families and the wider Hanan Mohamed al-Kuwari and HE measure and global health standards. community. Hthe Minister of Municipality and En- HE the Minister of Public Health Dr al- The visit comes as part of a number of vironment Abdullah bin Abdulaziz bin Turki Kuwari praised the eff orts exerted by vari- fi eld visits by health leaders at the Minis- al-Subaie inspected the newly established ous authorities in the country to confront try of Public Health and Hamad Medical Umm Slal quarantine compound which was the spread of the coronavirus disease, not- Corporation to ensure the implementation prepared as part of the precautionary and ing the high readiness of health teams to of preparedness and readiness plans to pre- preventive measures taken by Qatar against deal with this pandemic. -

QP Annual Review 2018

2018 ANNUAL REVIEW CONTENTS Message from the President & CEO 5 About QP 7 Company Profile Board of Directors QP’s Executive Leadership Team Corporate Governance, Transparency and Business Ethics Key Figures for 2018 17 Upstream Operations 19 QP-Operated Fields Dukhan Field Maydan Mahzam Field Bul Hanine Field Al Rayyan Field Non-QP-Operated Fields Al Shaheen Field Al Khalij Field Idd El Shargi – North Dome & South Dome Fields Al Karkara & A-Structures El Bunduq Field North Field Downstream Operations 31 QP Refinery Mesaieed Operations Refined Products Supply Chain Project Industrial Cities 35 Mesaieed Industrial City Ras Laffan Industrial City Dukhan Concession Area Major Projects 37 North Field Expansion Project Growing Global Reach 39 International Upstream Investments From Qatar to the World Joint Ventures & Subsidiaries 45 The QP Investment Portfolio The QP People Agenda 49 Qatarization Operating Safely and Responsibly 53 Occupational Health Safety Excellence Corporate Social Responsibility Environmental Stewardship 2018 Highlights 61 Financial Statements 69 Glossary & Acronyms 81 5 QATAR PETROLEUM ANNUAL REVIEW 2018 ANNUAL REVIEW 2018 2 His Highness Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani The Amir of the State of Qatar 3 QATAR PETROLEUM His Highness Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani The Father Amir ANNUAL REVIEW 2018 4 His Highness Sheikh Abdullah bin Hamad Al Thani The Deputy Amir of the State of Qatar 5 QATAR PETROLEUM MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT & CEO SAAD SHERIDA AL-KAABI Minister of State for Energy Affairs President & CEO of Qatar Petroleum ANNUAL REVIEW 2018 6 2018 was a robust and dynamic year, which was characterized by steady attention to Qatar Petroleum’s core business, a wider expansion of its international upstream footprint, and a detailed focus on the development of Qatar’s energy resources.