Laboratory Animal Act: a Legislative Proposal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CELEBRATING 135 YEARS 1877-2012 MHS Detroit, 2012

MHS Detroit, 1953 CELEBRATING 135 YEARS 1877-2012 MHS Detroit, 2012 ALSO IN THIS ISSUE: PUPPY PROTECTION ACT • PETS FOR PATRIOTS PROGRAM • CELEBRITY CHAT: JIM HARPER President’s Notes THOUGHTS FROM THE PRESIDENT & CEO he Michigan Humane Society is MICHIGAN HUMANE Tcelebrating a signifi- SOCIETY SERVICES cant milestone this year: our Adoption of Companion Animals 135th anniversary! While our focus and even our Animal Behavior Assistance name was different in the Animal Care/Protection Information late 1800s, we never have Cruelty Investigation wavered in our pursuit of what is best for animals and Education the community. I continue to Legislative Advocacy be very proud to lead such Rescue of Injured Animals a historic and respected ani- Wolka Jeff Photo by mal welfare organization. In February, MHS President and CEO Cal Morgan, pictured with Rusty, joined Reuniting Lost Animals In the early years, MHS legislators in Lansing for a press conference to introduce the Puppy Protection Act. With Their Owners almost was exclusively Shelter for Stray/ required to focus its limited spectrum of species, shapes interest of the animals or Abandoned/Unwanted Animals resources on alleviating and sizes, conditions and the community. Today, there immediate animal suffering. predicaments, MHS never are trends in animal welfare Spay/Neuter Program Today, while that remains a has wavered from taking on that are sometimes touted Veterinary Centers key focus of the organiza- the toughest cases, many of as “the” solution to quickly Volunteer Program tion, MHS also is proactive- which result in heartwarm- begin saving more lives. But ly targeting the root causes ing happy endings, but this what you won’t hear about Wildlife Care and Shelter of animal welfare issues. -

Animal Shelters List by County

MICHIGAN REGISTERED ANIMAL SHELTERS BY COUNTY COUNTY FACILITY NAME FACILITY ADDRESS CITY ZIP CODE PHONE Alcona ALCONA HUMANE SOCIETY 457 W TRAVERSE BAY STATE RD LINCOLN 48742 (989) 736-7387 Alger ALGER COUNTY ANIMAL SHELTER 510 E MUNISING AVE MUNISING 49862 (906) 387-4131 Allegan ALLEGAN COUNTY ANIMAL SHELTER 2293 33RD STREET ALLEGAN 49010 (269) 673-0519 COUNTRY CAT LADY 3107 7TH STREET WAYLAND 49348 (616) 308-3752 Alpena ALPENA COUNTY ANIMAL CONTROL 625 11th STREET ALPENA 49707 (989) 354-9841 HURON HUMANE SOCIETY, INC. 3510 WOODWARD AVE ALPENA 49707 (989) 356-4794 Antrim ANTRIM COUNTY ANIMAL CONTROL 4660 M-88 HWY BELLAIRE 49615 (231) 533-6421 ANTRIM COUNTY PET AND ANIMAL WATCH 125 IDA ST MANCELONA 49659 (231) 587-0738 HELP FROM MY FRIENDS, INC. 3820 RITT ROAD BELLAIRE 49615 (231) 533-4070 Arenac ARENAC COUNTY ANIMAL CONTROL SHELTER 3750 FOCO ROAD STANDISH 48658 (989) 846-4421 Barry BARRY COUNTY ANIMAL CONTROL SHELTER 540 N INDUSTRIAL PARK DR HASTINGS 49058 (269) 948-4885 Bay BAY COUNTY ANIMAL CONTROL SHELTER 800 LIVINGSTON BAY CITY 48708 (989) 894-0679 HUMANE SOCIETY OF BAY COUNTY 1607 MARQUETTE AVE BAY CITY 48706 (989) 893-0451 Benzie BENZIE COUNTY ANIMAL CONTROL SHELTER 543 S MICHIGAN AVE BEULAH 49617 (231) 882-9505 TINA'S BED AND BISCUIT INC 13030 HONOR HWY BEULAH 49617 (231) 645-8944 Berrien BERRIEN COUNTY ANIMAL SHELTER 1400 S EUCLID AVE BENTON HARBOR 49022 (269) 927-5648 HUMANE SOCIETY - SOUTHWESTERN MICHIGAN 5400 NILES AVE ST JOSEPH 49085 (269) 927-3303 Branch BRANCH COUNTY ANIMAL SHELTER 375 KEITH WILHELM DR COLDWATER 49036 (517) 639-3210 HUMANE SOCIETY OF BRANCH COUNTY, INC. -

Animal People News

European Commission votes to ban dog &cat fur B R U S S E L S ––The European Commis- sion on November 20 adopted a proposal to ban the import, export, and sale of cat and dog fur throughout the European Union. “The draft regulation will now be considered by the European Parliament and the Council of Ministers for adoption by the co- decision procedure,” explained the EC Asian dog. (Kim Bartlett) announcement. “There is evidence that cat and dog fur been found not just on clothing, but also on a is being placed on the European market, usually number of personal accessories, as well as chil- dren’s soft toys.” Asian rabbits. (Kim Bartlett) undeclared as such or disguised as synthetic and other types of fur,” the EC announcement sum- “Just the idea of young children playing marized. “The vast majority of the cat and dog with toys which have been made with dog and Olympics to showcase growing fur is believed to be imported from third coun- cat fur is really something we cannot accept,” tries, notably China.” European Consumer Protection Commissioner Fifteen of the 25 EU member nations Markos Kyprianou said. Chinese animal testing industry have already individually introduced legislation “Kyprianou stopped short of calling B E I J I N G ––The 2008 Olympic Glenn Rice, chief executive of Bridge against cat and dog fur. “The proposed regula- for every product containing fur to have a label Games in Beijing will showcase the fast- Pharmaceuticals Inc., is outsourcing the tion adopted today addresses EU citizens con- detailing its exact origin,” wrote London Times growing Chinese animal testing industry, work to China, where scientists are cheap cerns, and creates a harmonized approach,” the European correspondent David Charter, the official Xinhua news agency disclosed and plentiful and animal-rights activists are EC announcement stipulated. -

Kim Stallwood CV FINAL 16 Nov 2016

KIM STALLWOOD 1 Swan Avenue, Hastings, East Sussex TN34 3HX United Kingdom T +44(0)794-345-6815 ・Skype: kim.stallwood [email protected] ・www.kimstallwood.com PROFILE Kim Stallwood is an animal rights advocate and theorist, who is an author, independent scholar, consultant, and speaker. He has more than 40 years of personal commitment as a vegan and professional experience in leadership positions with some of the world’s foremost animal advocacy organisations. Currently, he is a consultant to Philip Lymbery, Chief Executive, Compassion In World Farming, in the UK and Becky Robinson, President and Founder, Alley Cat Allies, in the USA. He is the (volunteer) Executive Director of Minding Animals International. He wrote Growl: Life Lessons, Hard Truths, and Bold Strategies from an Animal Advocate with a Foreword by Brian May (Lantern Books, 2014). He became a vegetarian in 1974 after working in a chicken slaughterhouse. He has been a vegan since 1976. He has dual citizenship with the UK and USA. EXPERTISE Animal Rights Advocacy Theory and Practice Vegan, Cruelty-Free Living Social Justice Strategic Planning Writing and Editing Presentations Social Media Organisational Management Fundraising and Capacity Building Program Development PUBLICATIONS BOOKS & MAGAZINES Editor, The Evolution of the Cat Revolution: Celebrating 25 Years of Saving Cats by Becky Robinson (Bethesda, MD: Alley Cat Allies, 2015) Author, Growl. Life Lessons, Hard Truths, and Bold Strategies from an Animal Advocate (New York: Lantern Books, 2014) Co-Editor, Teaching About -

Should We Hunt Gray Wolves in Michigan?

SHOULD WE HUNT GRAY WOLVES IN MICHIGAN? AUGUST 2018 Dean’s Welcome Welcome, SEAS students! Before you know it, you will be boarding a bus with your classmates, headed for the University of Michigan Biological Station (the “Biostation”) in beautiful Northern Michigan—or “Up North” as Michiganders call it. There, during an immersive orientation experience, you will explore, learn, bond—and become an integral part of our community. This is just the beginning of your graduate career at SEAS, throughout which we will work together to solve some of the world’s most complex environmental problems. This is why you chose SEAS, and why we chose you. It is all very exciting, and we cannot wait to get started. So, why wait? The following case study details an active issue in the state of Michigan: whether or not to allow a public wolf hunt. During your time at the Biostation, you will be asked to examine the issue from opposing, nuanced perspectives, challenging your own gut reaction to the problem. Discussions will be guided by the scientific, political, economic, and social analyses included in these pages. You will actively collaborate with your classmates to uncover and synthesize facts, ultimately building a responsible, sustainable policy recommendation on Michigan’s wolf population. To prepare, simply read the case study and let it simmer. There is no need to do additional research. Enjoy your time at orientation. Get to know your classmates. Explore the gorgeous landscape. And then, come September 4th, join us back at the Dana Building ready to launch your graduate education and set out on a path of meaningful work—work that will have an impact on generations to come. -

Caring for a Pet

FD001 Animal Science Caring for a Pet Purpose Youth describe the care and equipment needed to own and take care of a pet. Facts to Know Group size: three to four children per adult volunteer Time frame: group meeting 30 Background Knowledge to 60 minutes Young children usually are dishes. At night, the cage Recommended ages: should to be covered with a 5- to fascinated by live animals 7-year-olds (kindergarten through and excited to care for them. cloth to keep the bird from second grade) Sometimes youth do not realize getting chilled. Materials: the responsibility involved in Fish also can be great pets. They caring for a pet. All pets need take very little space or time. n Blank sheets of paper clean and fresh water, food, Everyday care is simple. Fish n Fabric scissors shelter and clean space. require daily feeding, frequent tank n Pencils Some pets need more everyday cleaning and fresh water. Tanks n Glue care and equipment than others. without filters need to be cleaned daily. Tanks with filters can go for n Old magazines with pictures For example, most cats need a several weeks without cleaning. of animals and things needed home, fresh food and water every One drawback to keeping fish to care for them day, a litter box and a special bed or cushion. Some cats, especially as pets is that fish never can be n Pet first aid kit supplies (see those who stay indoors all the handled. activity detail) time, need a scratching post and Hamsters are another great n Fleece material (approximately toys to keep them active and pet. -

Somebody Here Needs

2014/2015 MICHIGAN HUMANE SOCIETY REPORT TO THE COMMUNITY SOMEBODY HERE NEEDS YOU MICHIGAN HUMANE SOCIETY MISSION To end companion animal homelessness, to provide the highest quality service and compassion to the animals entrusted to our care, and to be a leader in promoting humane values. CHAIR OF THE BOARD VICE CHAIR SECRETARY TREASURER Daniel A. Wiechec Paul M. Huxley Beth Correa Dennis J. Harder BOARD OF DIRECTORS LEADERSHIP TEAM Linda S. Axe Matthew Pepper - President and CEO Gregory M. Capler David Williams - Senior Vice President and Chief Operations Officer Jan Ellis David Gregory - Senior Vice President and Chief Financial Officer Marianne T. Endicott Michael Robbins - Vice President and Chief Marketing Officer Laura A. Hughes Robert A. Fisher, D.V.M. - Vice President and Chief Scientific Officer Robert A. Lutz Kelley Meyers, D.V.M. - Vice President and Director of Veterinary Operations Charles F. Metzger Daniel H. Minkus, Esq. Rick Ruffner Peter Van Dyke DEAR FRIENDS AND SUPPORTERS... Since 1877, the Michigan Humane Society has protected, defended and celebrated the animals of Southeast Michigan. Reflect on that for a moment – 138 years. There were only 38 states when we opened our doors and our hearts. The Civil War had only just ended 11 years prior. Rutherford B. Hayes was in his first year as President. In 138 years, things change. The Michigan Humane Society is no different. We have evolved over the years, increasing in scope and impact. The evolution of MHS has been nothing short of incredible. We are the largest and oldest animal welfare organization in Michigan. We stand as one of the most influential, impactful and lifesaving animal welfare organizations in the country. -

THECONNECTION October 10, 2019 - Issue 27

THECONNECTION October 10, 2019 - Issue 27 EXPLORING A NEW POTENTIAL VOLUNTEER POSITION By Annual Funds Associate, Sumi Alarabi Last month, I, along with other staff members, was asked to participate in a beta test for a new possible volunteer role. The position was for a Lobby Host at the MHS clinics. Leadership got together and created this role in the hope that a clinic “greeter” could help improve guests’ experience and assist receptionists at peak times. The Lobby Host’s main purpose would be to greet, inform, and thank guests when they enter the clinics. They also perform other duties such as tidying and cleaning up messes, making sure that pets are secure, and engaging with guests during their wait times. My trial shift was at the Berman Center clinic in Westland on September 24th. When I arrived, I met with my designated point person, Melissa. She gave me a quick tour of where to find the cleaning supplies and where the restroom for the clients was located. She then made some suggestions as to how I could assist while they were busy that morning. —for example, helping to open the door for guests with walkers or strollers and people who had their hands full, or helping guests sign in and having a seat while the receptionists were assisting clients on the phone. Whenever I noticed someone was waiting for a while, I would apologize for the wait and engage them in friendly conversation about their pets. At one point there seemed to be an accident in the corner, which I promptly cleaned up to maintain a clean environment for the clients. -

Animal Law Newsletter

State Bar of Michigan SectionAnimal Newsletter Law Early Summer 2017 Animal Law, Cats, and Me – Table of Contents Working as a Legislative Attorney Animal Law, Cats, and Me – Working as a Legislative Attorney for Best for Best Friends Animal Society Friends Animal Society ...................1 Co-Editor’s Note .................................2 By Richard Angelo Section Co-Sponsors Brunch with Harvard Law Animal Law & Policy Working as a Sole Practioner Fellow, Delcianna Winders..............4 I have been fortunate in my legal career as a sole practitioner to be able to focus a large Wanda Nash and Sadie Awards portion of my practice on issues involving companion animal-related matters. Defending Ceremonies in May 2017 ................5 unfairly accused dogs around the state was a primary niche for me, but I was also able to Section Members Save Three Dogs focus on community cat issues, state regulatory matters, and representing animal rescues Condemned to Death ......................6 and licensed shelters in a variety of interesting situations. About 7 years ago, I became more involved in political issues regarding breed discrimination, community cats, and Update on Legal Efforts to Free animal sheltering, as well as statutory and ordinance reform in those areas. Chimps Hercules, Leo, and Tommy .. 7 In 2015, I was lucky enough to be presented with an opportunity to take a posi- Historic Partnership Formed to Help tion with Best Friends Animal Society (http://bestfriends.org/), a national animal welfare Animal Abuse Victims .....................7 organization and operator of the largest no-kill animal sanctuary in the country. I had known and admired the work of Best Friends for many years and was elated when the Recent Animal Law News ...................9 opportunity arose. -

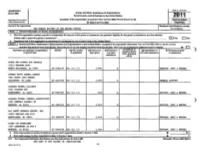

SCHEDULE I OMB No

SCHEDULE I OMB No. 1545-0047 (Form 990) Grants and Other Assistance to Organizations, Governments, and Individuals in the United States 2011 Department of the TreesUl)' Complete if the organization answered "Yes" to Form 990, Part IV, line 21 or 22. Internal Revenue Service ~ Attach to Form 990. Name of the organization Employer identification number THE HUMANE SOCIETY OF THE UNITED STATES 53-0225390 General Information on Grants and Assistance 1 Does the organization maintain records to substantiate the amount of the grants or assistance, the grantees' eligibility for the grants or assistance, and the selection criteria used to award the grants or assistance? ....... .......................................... ................................... .................................... ......................... ................................... 1]:1 Yes DNo 2 Describe in Part IV the or anization's rocedures for monitoTin the use of rant funds in the United States. lJ~a'1: II Grants and Other Assistance to Governments and Organizations in the United States. Complete if the organization answered "Yes" to Form 990, Part IV, line 21, for any recipient that received more than $5,000. Check this box if no one recipient received more than $5,000_ Part II can be duplicated if additional space is needed........................... ~ 0 1 (a) Name and address of organization (b) EIN (c) IRC section (d) Amount of (e) Amount of (~J Memoa OT (g) Description of (h) Purpose of grant ) valuation (book, or govemment if applicable cash grant non-cash non-cash assistance FMV, appraisal, or assistance assistance other) ACTOR AND OTHERS FOR ANIMALS 11523 BURBANK BLVD NORTH HOLLYWOOD, CA 91601 95-2783139 ~01 (e) (3) 2,000, O. SUPPORT: SPAY &: NEUTER AFGHAN STRAY ANIMAL LEAGUE 3823 SOUTH 14TH STREET ARLINGTON, VA 22204 20-2119782 ~01 (e) (3) 3,200, O. -

Animal House Sponsorship Opportunities

ANIMAL HOUSE SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES Saturday, November 16, 2019 | Russell Industrial Center | Detroit, MI ABOUT ANIMAL HOUSE 4 CATEGORY EXCLUSIVITY 5 SPONSORSHIP LEVELS 6-8 CONTACT 9 TABLE OF CONTENTS OF TABLE 2 39 A PARTY TO BARK ABOUT On November 16, make sure Felix is fed and Spot is put to bed — it’s time to get down and party like animals in the name of the Michigan Humane Society. A posh ambience paired with live music and the city’s most stylish animal lovers and influencers will make this an unforgettable night. Be among the first to experience the inaugural nighttime party of Michigan Humane — Animal House. Trailblazers from the animal welfare community and people hip to the Detroit party scene will join us at the Russell Industrial Center from 7 p.m. until midnight for an entirely cruelty-free environment, the first party of its kind in Detroit. Guests will enjoy a night of sophisticated h’ors doeuvres and divine cocktails from Forte Belanger and the best live music in Detroit with a DJ set by Juan Atkins. All funds raised will be restricted to our most impactful program — cruelty investigation and emergency rescue. Help drive positive change in our city by committing your support. Get your brand in front of a receptive and passionate audience at this groundbreaking event. Through on-site activations, larger-than-life branding opportunities, category exclusivity, and exposure to a quarter million social media followers, don’t miss out on the chance to tie your brand to the hottest party in town. Founded in 1877, the Michigan Humane Society is the oldest and largest animal welfare organization in the state. -

Better, Faster, Stronger, Kinder

B TTER FASTER STRONGERKINDER tBl4t104t•1, 'l-J i•1: tBl4t, 'td l BY RUTHANNE JOHNSON & MICHAEL SHARP DID YO HEA the one about the Lion who befriended a bulldog? This was late last year. Rosie had arrived at the Michigan Humane Society with a battered past and a case of heartworm. But her life was about to take a star turn. Golden Tate-a wide receiver with the NFL's Detroit Lions-and his girlfriend, Elise, agreed to foster Rosie.They too her on a trip to a pet supply store.They dressed her up in a lion outfit.They lounged with her on the couch, played with her on the floor and helped her start to overcome her fears of men, the outdoors and loud noises. And they chronicled the experience in a video for the Michigan Humane Society-a video that helps spotlight fostering and shelter animals, a video that ends with Rosie getting adopted. Fostering remains important to the couple. "Only problem is we both get emotionally attached to them and then we hate to see them go;'Tate said in April while filming an HSUS video to raise awareness about puppy mills. "But we feel like we could do more good with fostering and with working with the humane society and still take advantage of our passion fordogs, or [all] animals really:' Tate is one of many athletes making a differencefor animals by donating time, drawing attention to issues or becoming yet another shining example of the heights one can reach on a plant-based diet.