Authority and Spectacle in Medieval and Early Modern Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trastevere a Porte Aperte

Trastevere a Porte Aperte 1 ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Turismo Culturale Italiano prenotazioni +39.06.4542.1063 [email protected] informazioni www.turismoculturale.org Trastevere a Porte Aperte TRASTEVERE A PORTE APERTE 2 3 / 30 APRILE 2018 – I EDIZIONE Turismo Culturale Italiano ha programmato la I Edizione di questa iniziativa che si svolgerà a Roma dal 3 al 30 aprile. Questo nuovo evento, che si affianca alle precedenti edizioni di Palazzi e Ville di Roma a Porte Aperte, prevede l’apertura di chiese, palazzi, ville e giardini dello storico quartiere di Trastevere, tra i più popolari e intriganti rioni di Roma che conserva ancora oggi angoli e scorci intatti. Il programma si articola in un ricco programma di visite guidate in luoghi capaci di raccontare la storia del rione: dagli antichi sotterranei di Santa Cecilia a quelli di San Pasquale Baylonne, dalle piccole chiese romaniche di San Benedetto in Piscinula o Santa Maria in Cappella agli splendori berniniani in San Giacomo alla Lungara, dall’antica Farmacia di Santa Maria della Scala alla villa Aurelia Farnese, dalle architetture settecentesche dell’ex carcere nel complesso di San Michele a Ripa Grande fino al capolavoro di Moretti della ex-GIL. In programma anche una serie di passeggiate e itinerari urbani tra le caratteristiche vie, piazze e vicoli volte alla scoperta di aneddoti, curiosità, aspetti insoliti e poco conosciuti del popolare rione. Trastevere è pronta a svelare i suoi tesori. Vi aspettiamo! -

039-San Pancrazio.Pages

(39/20) San Pancrazio San Pancrazio is a 7th century minor basilica and parish and titular church, just west of Trastevere. This is in the suburb of Monteverde Vecchio, part of the Gianicolense quarter. The church is up a driveway from the road, and is surrounded by the park of the Villa Doria Pamphilj. The dedication is to St Pancras. History The basilica is on the site of the tomb of St Pancras, an early 4th century martyr. Unfortunately his legend is unreliable, but his veneration is in evidence from early times. The revised Roman martyrology carefully states in its entry for 12 May: "St Pancras, martyr and young man who by tradition died at the second milestone on the Via Aurelia". The actual location is on the present Via Vitellia, which is possibly an ancient road in its own right. The legend alleges that the body of the martyr was interred by a pious woman called Octavilla. This detail is thought to preserve the name of the proprietor of the cemetery in which the martyr was buried, which as a result is also called the Catacombe di Ottavilla. The re-laying of the church's floor in 1934 revealed some of the original surface cemetery (cimitero all'aperto), which began as a pagan burial ground in the 1st century. Three columbaria or "gardens of remembrance" for funerary ashes were found. This cemetery around the saint's tomb was extended as a Christian catacomb beginning at the start of the 4th century, with four separate identifiable foci. The earliest area seems to be contemporary with his martyrdom. -

The Porta Del Popolo, Rome Pen and Brown Ink on Buff Paper

Muirhead BONE (Glasgow 1876 - Oxford 1953) The Porta del Popolo, Rome Pen and brown ink on buff paper. Signed Muirhead Bone at the lower right. 222 x 170 mm. (8 3/4 x 6 5/8 in.) One of the first trips that Muirhead Bone made outside Britain was a long stay of two years - from October 1910 to October 1912 – in central and northern Italy, accompanied by his wife Gertrude and their children. After spending several weeks in Florence, the Bone family settled in Rome in the early months of 1911, and from October 1911 lived in a flat overlooking the Piazza del Popolo. During his time in Italy Bone produced thirty-two copper plates and numerous fine drawings, several of which were sent from Italy to London and Glasgow to be sold by his dealers. A number of Bone’s drawings of Italy were exhibited at the Colnaghi and Obach gallery in London in 1914, to very positive reviews. The present sheet depicts part of the outer façade of the city gate known as the Porta del Popolo, a section part of the Aurelian Walls encircling the city of Rome. The gate was the main entrance to Rome from the Via Flaminia and the north, and was used by most travellers arriving into the city for the first time. Built by Pope Sixtus IV for the Jubilee year of 1475, the Porta del Popolo was remodelled in the 16th century under Pope Pius IV. The Pope had asked Michelangelo to design the new outer façade of the Porta, but the elderly artist passed the commission on to the architect Nanni di Baccio Bigio, who completed the work between 1562 and 1565. -

Falda's Map As a Work Of

The Art Bulletin ISSN: 0004-3079 (Print) 1559-6478 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcab20 Falda’s Map as a Work of Art Sarah McPhee To cite this article: Sarah McPhee (2019) Falda’s Map as a Work of Art, The Art Bulletin, 101:2, 7-28, DOI: 10.1080/00043079.2019.1527632 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2019.1527632 Published online: 20 May 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 79 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcab20 Falda’s Map as a Work of Art sarah mcphee In The Anatomy of Melancholy, first published in the 1620s, the Oxford don Robert Burton remarks on the pleasure of maps: Methinks it would please any man to look upon a geographical map, . to behold, as it were, all the remote provinces, towns, cities of the world, and never to go forth of the limits of his study, to measure by the scale and compass their extent, distance, examine their site. .1 In the seventeenth century large and elaborate ornamental maps adorned the walls of country houses, princely galleries, and scholars’ studies. Burton’s words invoke the gallery of maps Pope Alexander VII assembled in Castel Gandolfo outside Rome in 1665 and animate Sutton Nicholls’s ink-and-wash drawing of Samuel Pepys’s library in London in 1693 (Fig. 1).2 There, in a room lined with bookcases and portraits, a map stands out, mounted on canvas and sus- pended from two cords; it is Giovanni Battista Falda’s view of Rome, published in 1676. -

AMERICAN ACADEMY in ROME PRESENTS the SCHAROUN ENSEMBLE CONCERT SERIES 14-16 JANUARY 2011 at VILLA AURELIA Exclusive Concert

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE January 11, 2011 AMERICAN ACADEMY IN ROME PRESENTS THE SCHAROUN ENSEMBLE CONCERT SERIES 14-16 JANUARY 2011 AT VILLA AURELIA Exclusive Concert Dates in Italy for the Scharoun Ensemble Berlin Courtesy of the Scharoun Ensemble Berlin Rome – The American Academy in Rome is pleased to present a series of three concerts by one of Germany’s most distinguished chamber music ensembles, the Scharoun Ensemble Berlin. Comprised of members of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, the Scharoun Ensemble Berlin specializes in a repertoire of Classical, Romantic, 20th century Modernist, and contemporary music. 2011 marks the third year of collaboration between the Ensemble and the American Academy in Rome, which includes performances of work by current Academy Fellows in Musical Composition Huck Hodge and Paul Rudy, as well as 2009 Academy Fellow Keeril Makan. Featuring soprano Rinnat Moriah, the Ensemble will also perform music by Ludwig van Beethoven, John Dowland, Antonin Dvořák, Sofia Gubaidulina, Heinz Holliger, Luca Mosca, and Stefan Wolpe. The concerts are free to the public and will take place at the Academy’s Villa Aurelia from 14-16 January 2011. Event: Scharoun Ensemble Berlin (preliminary program*) 14 January at 9pm – Ludwig van Beethoven, John Dowland, Huck Hodge, and Stefan Wolpe 15 January at 9pm – Sofia Gubaidulina, Huck Hodge, Heinz Holliger and Keeril Makan 16 January at 11am – Antonin Dvořák, Luca Mosca, and Paul Rudy *subject to change Location: Villa Aurelia, American Academy in Rome Largo di Porta San Pancrazio, 1 Scharoun Ensemble Berlin The Scharoun Ensemble Berlin was founded in 1983 by members of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. -

50Th Anniversary Guest Instructions

50th Anniversary Guest Instructions Welcome to the ICCS’s 50th Anniversary Celebration! Below are instructions for your tours and the gala dinner. Please see our staff and volunteers, if you have any questions. Tours Bring hats, water bottles, and sunscreen for all outdoor tours. The reverse side of your name badge lists the tours for which you are registered. Your name badge will serve as your ticket for all tours. We will also have lists of guests for each tour at each site. Check in with the tour leader at each site when you arrive. You may not switch tours. Tours will begin promptly at the times specified below. If you need to leave a tour early, you may do so. If you are on a bus or boat tour, please inform the tour leader before you go. City bus tickets may be purchased at tobacco and newspaper shops. Saturday Tours Below are the meeting times and places for all the Saturday tours: Archaeo-Culinary Tour: 9:00 Meet at the Piazza Testaccio fountain. Children’s Tour of the Capitoline Museums 9:30 Meet at Piazza del Campidoglio near the statue of Marcus Aurelius. Grown-ups Tour of the Sculpture Galleries, Capitoline Museums 9:30 Meet at Piazza del Campidoglio near the statue of Marcus Aurelius. Non-Catholic Cemetery Tour 10:00 Meet at the entrance of the Cemetery on Via Caio Cestio, 6. Near the Pyramid. Pantheon Tour: 10:00 Meet at the corner of Via Pantheon and Via Orfani in P.zza della Rotonda. Villa Doria Pamphili Tour: 9:00 Meet at the Centro. -

Manuel II Palaiologos' Point of View

The Hidden Secrets: Late Byzantium in the Western and Polish Context Małgorzata Dąbrowska The Hidden Secrets: Late Byzantium in the Western and Polish Context Małgorzata Dąbrowska − University of Łódź, Faculty of Philosophy and History Department of Medieval History, 90-219 Łódź, 27a Kamińskiego St. REVIEWERS Maciej Salamon, Jerzy Strzelczyk INITIATING EDITOR Iwona Gos PUBLISHING EDITOR-PROOFREADER Tomasz Fisiak NATIVE SPEAKERS Kevin Magee, François Nachin TECHNICAL EDITOR Leonora Wojciechowska TYPESETTING AND COVER DESIGN Katarzyna Turkowska Cover Image: Last_Judgment_by_F.Kavertzas_(1640-41) commons.wikimedia.org Printed directly from camera-ready materials provided to the Łódź University Press This publication is not for sale © Copyright by Małgorzata Dąbrowska, Łódź 2017 © Copyright for this edition by Uniwersytet Łódzki, Łódź 2017 Published by Łódź University Press First edition. W.07385.16.0.M ISBN 978-83-8088-091-7 e-ISBN 978-83-8088-092-4 Printing sheets 20.0 Łódź University Press 90-131 Łódź, 8 Lindleya St. www.wydawnictwo.uni.lodz.pl e-mail: [email protected] tel. (42) 665 58 63 CONTENTS Preface 7 Acknowledgements 9 CHAPTER ONE The Palaiologoi Themselves and Their Western Connections L’attitude probyzantine de Saint Louis et les opinions des sources françaises concernant cette question 15 Is There any Room on the Bosporus for a Latin Lady? 37 Byzantine Empresses’ Mediations in the Feud between the Palaiologoi (13th–15th Centuries) 53 Family Ethos at the Imperial Court of the Palaiologos in the Light of the Testimony by Theodore of Montferrat 69 Ought One to Marry? Manuel II Palaiologos’ Point of View 81 Sophia of Montferrat or the History of One Face 99 “Vasilissa, ergo gaude...” Cleopa Malatesta’s Byzantine CV 123 Hellenism at the Court of the Despots of Mistra in the First Half of the 15th Century 135 4 • 5 The Power of Virtue. -

Roman Empire Roman Empire

NON- FICTION UNABRIDGED Edward Gibbon THE Decline and Fall ––––––––––––– of the ––––––––––––– Roman Empire Read by David Timson Volum e I V CD 1 1 Chapter 37 10:00 2 Athanasius introduced into Rome... 10:06 3 Such rare and illustrious penitents were celebrated... 8:47 4 Pleasure and guilt are synonymous terms... 9:52 5 The lives of the primitive monks were consumed... 9:42 6 Among these heroes of the monastic life... 11:09 7 Their fiercer brethren, the formidable Visigoths... 10:35 8 The temper and understanding of the new proselytes... 8:33 Total time on CD 1: 78:49 CD 2 1 The passionate declarations of the Catholic... 9:40 2 VI. A new mode of conversion... 9:08 3 The example of fraud must excite suspicion... 9:14 4 His son and successor, Recared... 12:03 5 Chapter 38 10:07 6 The first exploit of Clovis was the defeat of Syagrius... 8:43 7 Till the thirtieth year of his age Clovis continued... 10:45 8 The kingdom of the Burgundians... 8:59 Total time on CD 2: 78:43 2 CD 3 1 A full chorus of perpetual psalmody... 11:18 2 Such is the empire of Fortune... 10:08 3 The Franks, or French, are the only people of Europe... 9:56 4 In the calm moments of legislation... 10:31 5 The silence of ancient and authentic testimony... 11:39 6 The general state and revolutions of France... 11:27 7 We are now qualified to despise the opposite... 13:38 Total time on CD 3: 78:42 CD 4 1 One of these legislative councils of Toledo.. -

The Dialogue of Emperor Manuel II Paleologus. Context and History Bogdan TIMARIU

The Dialogue of Emperor Manuel II Paleologus. Context and History Bogdan TIMARIU Summary This article will try to offer a description of the context and history of the Dialogue with a Persian, a literary work belonging to the byzantine emperor Manuel II Palaeologus. I will start by presenting the life of the author, emphasizing the general aspects of the important activities and events during his life, which had an impact on the visions of the emperor and influenced his thinking, as reflected in his own writings. These aspects point mostly to the declining of the byzantine state and the servitude towards the Muslim-Turkish enemy. The largest opera of the emperor (the Greek text published in 1966 expands on 301 pages), but neglected until our time by scholars, The Dialogue with a worthy Persian mouterizes in Ancyra of Galatia is a remarkably rich work, both literary and because of its thematic, with a high level of theology and spirituality, placed in the context of interreligious dialogue between a Christian and a Muslim. The environment of its appearance is important since it includes several aspects that have caught public attention even today, especially in September 2006, when pope Benedict XVI quoted a critical passage regarding Islam from the Dialogue. This study will focus on the general aspects of the Dialogue and the context of its creation, seen as relevant for understanding its purpose in the nowadays interreligious dialogue. Keywords Byzantium; Manuel al II-lea Palaeologus; Islam; dialogue; Muslim polemics This paper was presented in a doctoral student’s colloquium, organized between 11-14 January 2018 in Bern, Switzerland by Prof. -

Rom | Geschichte - Römisches Reich Internet

eLexikon Bewährtes Wissen in aktueller Form Rom | Geschichte - Römisches Reich Internet: https://peter-hug.ch/lexikon/rom/w1 MainSeite 13.897 Rom 7 Seiten, 26'128 Wörter, 184'216 Zeichen Rom. Übersicht der zugehörigen Artikel: Die antike Stadt Rom (Beschreibung) S. 897 Die heu•tige Provinz Rom 903 Die heu•tige Hauptstadt Rom (Beschreibung) 903 Ge•schichte der Stadt Rom seit 76 n. Chr. 912 Der alte römische Staat (Artikel »Römisches Reich«) 933 Ge•schichte des altrömis•chen Staats 940 Rom (Roma), Hauptstadt des röm. Weltreichs (s. Römisches Reich), in der Landschaft Latium am Tiber unterhalb der Einmündung des Anio gelegen, da, wo die Schiffbarkeit des Stroms beginnt und das Thal desselben in seinem Unterlauf am meisten von Hügeln eingeengt wird (s. den Plan, S. 898). Die Ortslage war in den tiefer gelegenen Teilen sumpfig, den Überschwemmungen des Tiber ausgesetzt und daher ziemlich ungesund. Die ältesten Erinnerungen städtischen Anbaues knüpfen sich an den isolierten Palatinischen Berg, die sogen. Roma quadrata, welche mit ihren drei Thoren als Gründung des Romulus galt. Die Tradition läßt Rom unter der Königsherrschaft dann in folgender Weise sich vergrößern. Zur Roma quadrata kam zunächst die folgenreiche Ansiedelung der Sabiner unter Titus Tatius auf dem Mons Capitolinus und der Südspitze des Collis Quirinalis, das sogen. Capitolium Vetus, hinzu. Auch die nordöstlich an den Mons Palatinus stoßende Anhöhe Velia ward frühzeitig mit Heiligtümern und Ansiedelungen besetzt; ebenfalls schon in alter Zeit ward ferner der Cälius mit etruskischen Geschlechtern unter Cäles Vibenna bevölkert. Der Aventinus ward unter Ancus Marcius von latinischen Städtegemeinden kolonisiert; dieser König überbrückte auch den Tiber und befestigte jenseit desselben den Janiculus. -

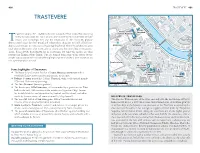

Trastevere (Map P. 702, A3–B4) Is the Area Across the Tiber

400 TRASTEVERE 401 TRASTEVERE rastevere (map p. 702, A3–B4) is the area across the Tiber (trans Tiberim), lying below the Janiculum hill. Since ancient times there have been numerous artisans’ Thouses and workshops here and the inhabitants of this essentially popular district were known for their proud and independent character. It is still a distinctive district and remains in some ways a local neighbourhood, where the inhabitants greet each other in the streets, chat in the cafés or simply pass the time of day in the grocery shops. It has always been known for its restaurants but today the menus are often provided in English before Italian. Cars are banned from some of the streets by the simple (but unobtrusive) method of laying large travertine blocks at their entrances, so it is a pleasant place to stroll. Some highlights of Trastevere ª The beautiful and ancient basilica of Santa Maria in Trastevere with a wonderful 12th-century interior and mosaics in the apse; ª Palazzo Corsini, part of the Gallerie Nazionali, with a collection of mainly 17th- and 18th-century paintings; ª The Orto Botanico (botanic gardens); ª The Renaissance Villa Farnesina, still surrounded by a garden on the Tiber, built in the early 16th century as the residence of Agostino Chigi, famous for its delightful frescoed decoration by Raphael and his school, and other works by Sienese artists, all commissioned by Chigi himself; HISTORY OF TRASTEVERE ª The peaceful church of San Crisogono, with a venerable interior and This was the ‘Etruscan side’ of the river, and only after the destruction of Veii by remains of the original early church beneath it; Rome in 396 bc (see p. -

Rome 2016 Program to SEND

A TASTE OF ANCIENT ROME 17–24 October 2016 Day-by-Day Program Elizabeth Bartman, archaeologist, and Maureen Fant, food writer, lead a unique, in-depth tour for sophisticated travelers who want to experience Rome through the eyes of two noted specialists with a passion for the city, its monuments, and its cuisine. Together they will introduce you to the fascinating archaeology of ancient foodways and to the fundamentals of modern Roman cuisine. Delicious meals, special tastings, and behind-the-scenes visits in Rome and its environs make this week-long land trip an exceptional experience. You’ll stay in the same hotel all week, in Rome’s historic center, with some out-of-town day trips. October is generally considered the absolutely best time to visit Rome. The sun is warm, the nights not yet cold, and the light worthy of a painting. The markets and restaurants are still offering the last of the summer vegetables—such as Rome’s particular variety of zucchini and fresh borlotti beans—as well as all the flavors of fall and winter in central Italy—chestnuts, artichokes, broccoli, broccoletti, chicory, wild mushrooms, stewed and roasted meats, freshwater fish, and so much more. Note: Logistics, pending permissions, and new discoveries may result in some changes to this itinerary, but rest assured, plan B will be no less interesting or delicious. B = Breakfast included L = Lunch included D = Dinner included S = Snack or tasting included MONDAY: WELCOME AND INTRODUCTION You’ll be met at Leonardo da Vinci Airport (FCO) or one of the Rome railroad stations and transferred to our hotel near the Pantheon, our base for the next seven nights.