Twitchell Dam Litigation Q&A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Santa Maria Project

MP Region Public Affairs, 916-978-5100, http://www.usbr.gov/mp, February 2016 Mid-Pacific Region, Santa Maria Project Construction individual landholders pump water according to The Santa Maria Project, authorized in 1954, is their needs. The objective of the project as located in California about 150 miles northwest authorized is to release regulated water from of Los Angeles. A joint water conservation and storage as quickly as it can be percolated into flood control project, it consists of the the Santa Maria Valley ground-water basin. Twitchell Dam where construction began in With this type of operation, Twitchell July 1956 and was completed in October Reservoir is empty much of the time. For this 1958.The Reservoir was constructed by the reason, recreation and fishing facilities are not Bureau of Reclamation, and a system of river included in the project. levees was constructed by the Corps of Engineers. Twitchell Dam Twitchell Dam is located on the Cuyama River about 6 miles upstream from its junction with the Sisquoc River. The dam regulates flows along the lower reaches of the river and impounds surplus flows for release in the dry months to help recharge the ground-water basin underlying the Santa Maria Valley, thus minimizing discharge of water to the sea at Guadalupe. The dam is an earthen fill structure having a height of 241 feet with 216 feet above streambed, and a crest length of 1,804 feet. The dam contains approximately 5,833,000 yards of Twitchell Dam and Reservoir material. The multi-purpose Twitchell Reservoir Water Supply has a total capacity of 224,300 acre-feet. -

Southern Steelhead Populations Are in Danger of Extinction Within the Next 25-50 Years, Due to Anthropogenic and Environmental Impacts That Threaten Recovery

SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA STEELHEAD Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus Critical Concern. Status Score = 1.9 out of 5.0. Southern steelhead populations are in danger of extinction within the next 25-50 years, due to anthropogenic and environmental impacts that threaten recovery. Since its listing as an Endangered Species in 1997, southern steelhead abundance remains precariously low. Description: Southern steelhead are similar to other steelhead and are distinguished primarily by genetic and physiological differences that reflect their evolutionary history. They also exhibit morphometric differences that distinguish them from other coastal steelhead in California such as longer, more streamlined bodies that facilitate passage more easily in Southern California’s characteristic low flow, flashy streams (Bajjaliya et al. 2014). Taxonomic Relationships: Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) historically populated all coastal streams of Southern California with permanent flows, as either resident or anadromous trout, or both. Due to natural events such as fire and debris flows, and more recently due to anthropogenic forces such as urbanization and dam construction, many rainbow trout populations are isolated in remote headwaters of their native basins and exhibit a resident life history. In streams with access to the ocean, anadromous forms are present, which have a complex relationship with the resident forms (see Life History section). Southern California steelhead, or southern steelhead, is our informal name for the anadromous form of the formally designated Southern California Coast Steelhead Distinct Population Segment (DPS). Southern steelhead occurring below man-made or natural barriers were distinguished from resident trout in the Endangered Species Act (ESA) listing, and are under different jurisdictions for purposes of fisheries management although the two forms typically constitute one interbreeding population. -

Sisquoc River Steelhead Trout Population Survey Fall 2005

Sisquoc River Steelhead Trout Population Survey Fall 2005 February 2006 Prepared by: Matt Stoecker P.O. Box 2062 Santa Barbara, Ca. 93120 [email protected] www.StoeckerEcological.com Prepared for: Community Environmental Council 26 W. Anapamu St. 2nd Floor Santa Barbara, Ca. 93101-3108 California Department of Fish and Game TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover Page 1 Table of Contents 2 List of Figures 3 Project Background 4 Santa Maria/Sisquoc River Steelhead 4 Project Methods 5 Personnel 5 Survey Access and Locations 5 Fish Sampling Methods 6 Fish Sampling Table Definitions 6 Survey Results 8 Lower Sisquoc River 8 Upper Sisquoc River 12 Manzana Creek 15 Davy Brown Creek 18 South Fork Sisquoc River 20 Rattlesnake Creek 23 Key Steelhead Population Findings 24 Sisquoc River Watershed Lower Sisquoc River 24 Upper Sisquoc River 25 Manzana Creek 25 Davy Brown Creek 25 South Fork Sisquoc River 26 Rattlesnake Creek 26 Steelhead and Chub Relationship 26 Steelhead Run Observations by Forest Service Personnel 28 Twitchell Dam and Migration Flow Discussion 29 Twitchell Dam Background 29 Impacts on Steelhead 29 Recommended Action for Improving Steelhead Migration Flows 30 Additional Recommended Studies 32 Adult Steelhead Monitoring Program 32 Exotic Fish Species Recommendation 32 Fish Passage Improvements 32 References 33 Personal Communications 33 Appendix A- Sisquoc River Area Map 34 Appendix B- Stream Reach Survey Maps (1-3) 35 Appendix C- Survey Reach GPS Coordinates 38 Appendix D- DFG Habitat Type Definitions 39 2 LIST OF FIGURES Lower Sisquoc River Steelhead Sampling Results Table 10 Upper Sisquoc River Steelhead Sampling Results Table 13 Manzana Creek Steelhead Sampling Results Table 16 Davy Brown Creek Steelhead Sampling Results Table 19 South Fork Sisquoc River Steelhead Sampling Results Table 21 Rattlesnake Creek Steelhead Sampling Results Table 23 Steelhead Sampling Results- Watershed Survey Totals Table 24 All photographs by Stoecker and Allen. -

28 Critical Habitat Units for the California Red-Legged Frog In

28 Critical Habitat Units for the California Red-Legged Frog In response to a 12-20-99, federal court order won by the Center for Biological Diversity, the Jumping Frog Research Institute, the Pacific Rivers Council and the Center for Sierra Nevada Conservation, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service designated 4,138,064 acres of critical habitat for the California red-legged frog. The March 6, 2001 designation is comprised of 29 units spanning 28 California counties. UNIT ACRES COUNTY WATERSHEDS AND OWNERSHIP North Fork Feather 115,939 Butte Drainages within the North Fork Feather River watershed including the River Plumas French Creek watershed. 81% Plumas and Lassen National Forests, 19% mostly private land. Weber 59,531 El Dorado Drainages in Weber Creek and North Fork Cosumnes River watersheds. Creek-Cosumnes 64% private lands, 36% El Dorado National Forest Yosemite 124,336 Tuolumne Tributaries of the Tuolumne River and Jordan Creek, a tributary to the Mariposa Merced River 100% Stanislaus National Forest or Yosemite National Park. Headwaters of 38,300 Tehama Includes drainages within the headwaters of Cottonwood and Red Bank Cottonwood Creek creeks. 82 % private lands, 18% Mendocino National Forest. Cleary Preserve 34,087 Napa Drainages within watersheds forming tributaries to Pope Creek 88% private, 12% federal and state Annadel State Park 6,326 Sonoma Upper Sonoma Creek watershed found partially within Annadel State Preserve Park. 76% private, 24% California Department of Parks and Recreation Stebbins Cold 21,227 Napa Drainages found within and adjacent to Stebbins Cold Canyon Preserve Canyon Preserve Solano and the Quail Ridge Wilderness Preserve including watersheds that form Capell Creek, including Wragg Canyon, Markley Canyon, Steel Canyon and the Wild Horse Canyon watershed. -

Santa Maria Project History

Santa Maria Project Thomas A. Latousek Bureau of Reclamation 1996 Table of Contents The Santa Maria Project ........................................................2 Project Location.........................................................2 Historic Setting .........................................................3 Prehistoric Setting .................................................3 Historic Setting ...................................................4 Authorization...........................................................6 Construction History .....................................................9 Post-Construction History................................................10 Settlement of the Project .................................................12 Uses of Project Water ...................................................13 Conclusion............................................................13 Bibliography ................................................................15 Manuscripts and Archival Material.........................................15 Project Reports, Santa Maria Project..................................15 Government Documents .................................................15 Books ................................................................15 Interviews.............................................................15 Index ......................................................................16 1 The Santa Maria Project The beautiful, broad Santa Maria Basin opens eastward from the Pacific Ocean toward the Sierra -

2016 Annual Report of Hydrogeologic Conditions, Water Requirements, Supplies and Disposition

2016 Annual Report of Hydrogeologic Conditions, Water Requirements, Supplies and Disposition Santa Maria Valley Management Area Luhdorff and Scalmanini Consulting Engineers April, 2017 Landsat 5 Satellite Image taken November 14, 2008 2016 Annual Report of Hydrogeologic Conditions Water Requirements, Supplies, and Disposition Santa Maria Valley Management Area prepared by Luhdorff and Scalmanini Consulting Engineers April 27, 2017 Table of Contents Page 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................1 1.1 Physical Setting .................................................................................................1 1.2 Previous Studies ................................................................................................2 1.3 SMVMA Monitoring Program .........................................................................2 1.4 Additional Monitoring and Reporting Programs ..............................................4 1.5 Report Organization ..........................................................................................4 2. Hydrogeologic Conditions .................................................................................................5 2.1 Groundwater Conditions ...................................................................................5 2.1.1 Geology and Aquifer System ..............................................................5 2.1.2 Groundwater Levels ............................................................................8 -

Final Environmental Impact Statement - Los Padres National Forest Tamarisk Removal Project

Final Environmental Impact United States Department of Agriculture Statement Forest Service Los Padres National Forest September 2016 Tamarisk Removal Project Los Padres National Forest Kern, Los Angeles, Monterey, San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara and Ventura Counties, California In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877- 8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD- 3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. -

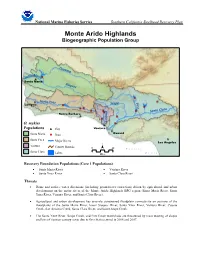

Monte Arido Highlands Biogeographic Population Group

National Marine Fisheries Service Southern California Steelhead Recovery Plan Monte Arido Highlands Biogeographic Population Group o Cuy ama ta Ma San ria Santa Maria Sis quoc San ta Ynez P Sespe i Lompoc r u V a Clara e Sant Santa Barbara n t u r a O. mykiss Populations City Ventura Santa Maria Dam Oxnard Santa Ynez Major Rivers Los Angeles Ventura County Boundary 020Pacific Santa Clara Lakes Ocean Miles Recovery Foundation Populations (Core 1 Populations) • Santa Maria River • Ventura River • Santa Ynez River • Santa Clara River Threats • Dams and surface water diversions (including groundwater extraction) driven by agricultural and urban development on the major rivers of the Monte Arido Highlands BPG region (Santa Maria River, Santa Ynez River, Ventura River, and Santa Clara River). • Agricultural and urban development has severely constrained floodplain connectivity on sections of the floodplains of the Santa Maria River, lower Sisquoc River, Santa Ynez River, Ventura River, Coyote Creek, San Antonio Creek, Santa Clara River, and lower Sespe Creek. • The Santa Ynez River, Sespe Creek, and Piru Creek watersheds are threatened by mass wasting of slopes and loss of riparian canopy cover due to fires that occurred in 2006 and 2007. Santa Maria River Santa Clara River Steelhead – 28 inches Matilija Dam Critical Recovery Actions • Implement operating criteria to ensure the pattern and magnitude of water releases from Bradbury, Gibraltar, Juncal, Twitchell, Casitas, Matilija, Robles Diversion, Vern Freeman Diversion, Santa Felicia, Pyramid, and Castaic dams comport with the natural or pre-dam pattern and magnitude of stream flow in downstream reaches. Physically modify these dams to allow unimpeded volitional migration of steelhead to upstream spawning and rearing habitats. -

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 01/01/2017 to 03/31/2017 Los Padres National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 01/01/2017 to 03/31/2017 Los Padres National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Los Padres National Forest, Forestwide (excluding Projects occurring in more than one Forest) R5 - Pacific Southwest Region AT&T California Master Special - Special use management On Hold N/A N/A David Betz Use Permit Renewal 530-841-6131 CE [email protected] Description: AT&T requests to renew & consolidate all existing linear rights-of-way special use authorizations into 1 master permit for a 30-yr. term. Existing facilities are on the Monterey, Santa Lucia, Mt. Pinos & Ojai Districts. One line is in Black Mt. IRA. Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=38986 Location: UNIT - Los Padres National Forest All Units. STATE - California. COUNTY - Kern, Los Angeles, Monterey, San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara, Ventura. LEGAL - Multiple locations in Monterey, San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara, Ventura, Los Angeles & Kern Counties. Telephone communication line - linear rights-of-way - across all districts except Santa Barbara Ranger District. Los Padres Campground - Recreation management Completed Actual: 10/26/2016 11/2016 Jeff Bensen Concessionaire Special Use 805-961-5744 Permit [email protected] CE Description: Issue Forest wide concessionaire special use permit to replace expiring permits. *UPDATED* Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=50421 Location: UNIT - Los Padres National Forest All Units. STATE - California. COUNTY - Santa Barbara. LEGAL - Not Applicable. -

Wildlife Biological Assessment/Evaluation for Santa Barbara Front Country DFPZ, Santa Barbara Ranger District, Los Padres National Forest

Wildlife Biological Assessment/Evaluation for Santa Barbara Front Country DFPZ, Santa Barbara Ranger District, Los Padres National Forest Prepared by: Date: 31 August 2015 Patrick Lieske, Asst. Forest Biologist Los Padres National Forest 1 1.0 Background Over the past half century, urban development has expanded into the chaparral and forested environments on the Santa Barbara Front. This expansion has placed residences adjacent to highly flammable wildland fuels that typically burn with high intensity and can pose a threat to both structures and residents alike. Much of this expansion of urban development has occurred next to National Forest boundaries without the adoption of sufficient provisions for the establishment of defensible space needed in the event of wildfire. The Santa Barbara Mountain Communities Defense Zone Project would be located on the Santa Barbara Ranger District, Los Padres National Forest. We propose several activities covering a total of approximately 418 acres to directly improve the ability of the communities of Painted Cave, San Marcos Trout Club, Haney Tract, Rosario Park, Refugio, and Gaviota to address this threat. This project would create or expand on existing fuel breaks, reducing the amount of standing vegetation to improve the ability of the communities to strategically mitigate the potential impacts of wildfire. Project Description The proposed project would be located on the Santa Barbara Front in the Santa Ynez Mountains. This area is north of U.S. Highway 101, in Santa Barbara County, California. It overlooks the Pacific Ocean between Santa Barbara, and Gaviota, California (Figure 1). Historic Condition The proposed project area has a Mediterranean climate and its chaparral ecosystem is considered to be one of the most fire hazardous landscapes in North America. -

8. Big Pine Mountain (Keeler-Wolf 1991A) Location This Candidate RNA Is on the Santa Lucia Ranger District, Los Padres National Forest

8. Big Pine Mountain (Keeler-Wolf 1991a) Location This candidate RNA is on the Santa Lucia Ranger District, Los Padres National Forest. The cRNA lies within the San Rafael and Dick Smith Wilderness, except for the narrow right-of-way surrounding Forest Service Road 9N11. It lies within portions of sections 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9 of T7N, R26W and sections 1 and 12 of T7N, R27W SBM (34°42'N., 119°40'W.), USGS Big Pine Mountain quad (fig. 16). Ecological subsection – San Rafael-Topatopa Mountains (M262Ba). Target Element Sierra Nevada Mixed Conifer Forest for the Central California Coast Ranges ecological section Figure 16—Big Pine Distinctive Features Mountain cRNA The stands of mixed conifer forest are limited to elevations above 5100 ft (1554 m) and are diverse and variable topographically and compositionally. Floristic varia- tion in the area results from the well-balanced diversity of plant associations cov- ering a range from low-elevation chaparral and riparian to montane chaparral and mixed conifer forest. In addition to the target vegetation, the cRNA also con- tains a number of other well-developed plant communities, including bigcone Douglas-fir/canyon live oak (Pseudotsuga macrocarpa/Quercus chrysolepis) forest, Coulter pine (Pinus coulteri)/chaparral vegetation, and such locally unique commu- nities as shale barrens. The riparian vegetation found in the cRNA is some of the best remaining vegetation of this type in the Central California Coast Ranges eco- logical section. Rare Plants: The cRNA contains one CNPS listed species. Sidalcea hickmanii ssp. parishii (CNPS List 1B) is found on dry, disturbed, sandy areas around fuel breaks and on fire roads along mountain summits. -

Los Padres National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 07/01/2016 to 09/30/2016 Los Padres National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Los Padres National Forest, Forestwide (excluding Projects occurring in more than one Forest) R5 - Pacific Southwest Region AT&T California Master Special - Special use management On Hold N/A N/A David Betz Use Permit Renewal 530-841-6131 CE [email protected] Description: AT&T requests to renew & consolidate all existing linear rights-of-way special use authorizations into 1 master permit for a 30-yr. term. Existing facilities are on the Monterey, Santa Lucia, Mt. Pinos & Ojai Districts. One line is in Black Mt. IRA. Web Link: http://www.fs.fed.us/nepa/nepa_project_exp.php?project=38986 Location: UNIT - Los Padres National Forest All Units. STATE - California. COUNTY - Kern, Los Angeles, Monterey, San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara, Ventura. LEGAL - Multiple locations in Monterey, San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara, Ventura, Los Angeles & Kern Counties. Telephone communication line - linear rights-of-way - across all districts except Santa Barbara Ranger District. Los Padres Tamarisk Removal - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants In Progress: Expected:12/2016 12/2016 Lloyd Simpson EIS - Vegetation management DEIS NOA in Federal Register 805-646-4348 ex. 316 [email protected] *UPDATED* (other than forest products) 06/10/2016 - Fuels management Est. FEIS NOA in Federal - Watershed management Register 09/2016 Description: An effort to remove tamarisk from all watersheds where it occurs in the Los Padres National Forest.