“Hinduism” Michel Picard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Penjor in Hindu Communities

Penjor in Hindu Communities: A symbolic phrases of relations between human to human, to environment, and to God Makna penjor bagi Masyarakat Hindu: Kompleksitas ungkapan simbolis manusia kepada sesama, lingkungan, dan Tuhan I Gst. Pt. Bagus Suka Arjawa1* & I Gst. Agung Mas Rwa Jayantiari2 1Department of Sociology, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Udayana 2Faculty of Law, Universitas Udayana Address: Jalan Raya Kampus Unud Jimbaran, South Kuta, Badung, Bali 80361 E-mail: [email protected]* & [email protected] Abstract The purpose of this article was to observe the development of the social meaning derived from penjor (bamboo decorated with flowers as an expression of thanks to God) for the Balinese Hindus. In the beginning, the meaning of penjor serves as a symbol of Mount Agung, and it developed as a human wisdom symbol. This research was conducted in Badung and Tabanan Regency, Bali using a qualitative method. The time scope of this research was not only on the Galungan and Kuningan holy days, where the penjor most commonly used in society. It also used on the other holy days, including when people hold the caru (offerings to the holy sacrifice) ceremony, in the temple, or any other ceremonial place and it is also displayed at competition events. The methods used were hermeneutics and verstehen. These methods served as a tool for the researcher to use to interpret both the phenomena and sentences involved. The results of this research show that the penjor has various meanings. It does not only serve as a symbol of Mount Agung and human wisdom; and it also symbolizes gratefulness because of God’s generosity and human happiness and cheerfulness. -

Interpreting Balinese Culture

Interpreting Balinese Culture: Representation and Identity by Julie A Sumerta A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Public Issues Anthropology Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2011 © Julie A. Sumerta 2011 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. Julie A. Sumerta ii Abstract The representation of Balinese people and culture within scholarship throughout the 20th century and into the most recent 21st century studies is examined. Important questions are considered, such as: What major themes can be found within the literature?; Which scholars have most influenced the discourse?; How has Bali been presented within undergraduate anthropology textbooks, which scholars have been considered; and how have the Balinese been affected by scholarly representation? Consideration is also given to scholars who are Balinese and doing their own research on Bali, an area that has not received much attention. The results of this study indicate that notions of Balinese culture and identity have been largely constructed by “Outsiders”: 14th-19th century European traders and early theorists; Dutch colonizers; other Indonesians; and first and second wave twentieth century scholars, including, to a large degree, anthropologists. Notions of Balinese culture, and of culture itself, have been vigorously critiqued and deconstructed to such an extent that is difficult to determine whether or not the issue of what it is that constitutes Balinese culture has conclusively been answered. -

Narrating Seen and Unseen Worlds: Vanishing Balinese Embroideries

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2000 Narrating Seen and Unseen Worlds: Vanishing Balinese Embroideries Joseph Fischer Rangoon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Fischer, Joseph, "Narrating Seen and Unseen Worlds: Vanishing Balinese Embroideries" (2000). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 803. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/803 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Narrating Seen and Unseen Worlds: Vanishing Balinese Embroideries Joseph Fischer Vanishing Balinese embroideries provide local people with a direct means of honoring their gods and transmitting important parts of their narrative cultural heritage, especially themes from the Ramayana and Mahabharata. These epics contain all the heroes, preferred and disdained personality traits, customary morals, instructive folk tales, and real and mythic historic connections with the Balinese people and their rich culture. A long ider-ider embroidery hanging engagingly from the eaves of a Hindu temple depicts supreme gods such as Wisnu and Siwa or the great mythic heroes such as Arjuna and Hanuman. It connects for the Balinese faithful, their life on earth with their heavenly tradition. Displayed as an offering on outdoor family shrines, a smalllamak embroidery of much admired personages such as Rama, Sita, Krisna and Bima reflects the high esteem in which many Balinese hold them up as role models of love, fidelity, bravery or wisdom. -

9789004400139 Webready Con

Vedic Cosmology and Ethics Gonda Indological Studies Published Under the Auspices of the J. Gonda Foundation Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Edited by Peter C. Bisschop (Leiden) Editorial Board Hans T. Bakker (Groningen) Dominic D.S. Goodall (Paris/Pondicherry) Hans Harder (Heidelberg) Stephanie Jamison (Los Angeles) Ellen M. Raven (Leiden) Jonathan A. Silk (Leiden) volume 19 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/gis Vedic Cosmology and Ethics Selected Studies By Henk Bodewitz Edited by Dory Heilijgers Jan Houben Karel van Kooij LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Bodewitz, H. W., author. | Heilijgers-Seelen, Dorothea Maria, 1949- editor. Title: Vedic cosmology and ethics : selected studies / by Henk Bodewitz ; edited by Dory Heilijgers, Jan Houben, Karel van Kooij. Description: Boston : Brill, 2019. | Series: Gonda indological studies, ISSN 1382-3442 ; 19 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019013194 (print) | LCCN 2019021868 (ebook) | ISBN 9789004400139 (ebook) | ISBN 9789004398641 (hardback : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Hindu cosmology. | Hinduism–Doctrines. | Hindu ethics. Classification: LCC B132.C67 (ebook) | LCC B132.C67 B63 2019 (print) | DDC 294.5/2–dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019013194 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill‑typeface. ISSN 1382-3442 ISBN 978-90-04-39864-1 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-40013-9 (e-book) Copyright 2019 by Henk Bodewitz. -

Cultural Orientation | Kurmanji

KURMANJI A Kurdish village, Palangan, Kurdistan Flickr / Ninara DLIFLC DEFENSE LANGUAGE INSTITUTE FOREIGN LANGUAGE CENTER 2018 CULTURAL ORIENTATION | KURMANJI TABLE OF CONTENTS Profile Introduction ................................................................................................................... 5 Government .................................................................................................................. 6 Iraqi Kurdistan ......................................................................................................7 Iran .........................................................................................................................8 Syria .......................................................................................................................8 Turkey ....................................................................................................................9 Geography ................................................................................................................... 9 Bodies of Water ...........................................................................................................10 Lake Van .............................................................................................................10 Climate ..........................................................................................................................11 History ...........................................................................................................................11 -

Government Interference in Religious Institutions and Terrorism Peter S. Henne Assistant Professor Department of Political Scien

0 Government interference in religious institutions and terrorism Peter S. Henne Assistant Professor Department of Political Science/Global and Regional Studies Program University of Vermont [email protected] 1 Abstract: Many states have adopted policies that monitor or attempt to control religious institutions in various ways. This ranges from limiting foreign born clerics to approving the sermons presented in these institutions. These policies are often justified as measures to limit religious strife or terrorism by minimizing extremism in the country. Are they effective? Or are they counterproductive, and promote resentment and violence? Using data from the Religion and State dataset and the Global Terrorism Database, I find that intensified government interference in religious institutions can lead to an increase in terrorism in a country. Bio: Peter S. Henne is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science and the Global and Regional Studies Program at the University of Vermont. He received his Ph.D in Government from Georgetown University, and B.A. in Political Science from Vassar College. His first book, Islamic Politics, Muslim States and Counterterrorism Tensions, was published in 2017 by Cambridge University Press. After the 2013 coup in Egypt, the new regime intensified state control of mosques throughout the country. 1 Government officials shut down mosques that did not have official approval and banned their clerics from preaching. The regime claimed the new policies were intended to counter extremist voices and prevent terrorist threats from arising (Economist 2014). Critics, however, saw these actions as infringements on human rights and a means to undermine political opposition (Economist 2014). -

Katie Russell Issue Brief: Native Americans and Minority Religion Keywords: Native Americans, Religious Freedom, First Amendment

Katie Russell Issue Brief: Native Americans and Minority Religion Keywords: Native Americans, Religious Freedom, First Amendment Rights, Religious Freedom Restoration Act, Christianity, Native American Religions Description: The following brief describes religious affiliation of Native Americans, with an emphasis on historical movements and legal difficulties that have impacted Native Americans religious identity (i.e. religious freedom). Additionally, current religious freedom struggles are addressed. Key Points: • Native Americans have historically struggled to obtain First Amendment rights related to religious freedom; this is due in part to their unconventional citizenship status. • The federal government’s historically meddlesome approach to Native American religious tradition has greatly influenced Native American’s form of worship, causing a departure from traditional Native American religions and shift towards Christianity. • The federal government resettled Indians, outlawed the practice of native religion, and put into place a series of assimilation programs until the creation of the New Deal in 1933 (which revoked many of these limitations). • Native Americans had the majority of their religious rights formally restored to them with the enactment of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act in the 1990’s. • Today, Native American’s primary religious struggles are to gain access to sacred sites and have sacred artifacts returned. They also face many opponents of their use of controversial items such as peyote and eagle feathers in rituals, despite being legally permitted to utilize these goods. Issue Brief: According to the 2010 United States Census, Native Americans make up approximately 1.7% of the population (5.4 million people) (Yurth). It is approximated that 9000 people, or less than 1% of this population, solely practice Native American religions which often incorporates a variety of ceremonies and symbolism focused on animalism (Ratts & Pedersen, 159). -

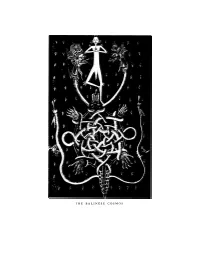

THE BALINESE COSMOS M a R G a R Et M E a D ' S B a L in E S E : T H E F Itting S Y M B O Ls O F T H E a M E R Ic a N D R E a M 1

THE BALINESE COSMOS M a r g a r et M e a d ' s B a l in e s e : T h e F itting S y m b o ls o f t h e A m e r ic a n D r e a m 1 Tessel Pollmann Bali celebrates its day of consecrated silence. It is Nyepi, New Year. It is 1936. Nothing disturbs the peace of the rice-fields; on this day, according to Balinese adat, everybody has to stay in his compound. On the asphalt road only a patrol is visible—Balinese men watching the silence. And then—unexpected—the silence is broken. The thundering noise of an engine is heard. It is the sound of a motorcar. The alarmed patrollers stop the car. The driver talks to them. They shrink back: the driver has told them that he works for the KPM. The men realize that they are powerless. What can they do against the *1 want to express my gratitude to Dr. Henk Schulte Nordholt (University of Amsterdam) who assisted me throughout the research and the writing of this article. The interviews on Bali were made possible by Geoffrey Robinson who gave me in Bali every conceivable assistance of a scholarly and practical kind. The assistance of the staff of Olin Libary, Cornell University was invaluable. For this article I used the following general sources: Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead, Balinese Character: A Photographic Analysis (New York: New York Academy of Sciences, 1942); Geoffrey Gorer, Bali and Angkor, A 1930's Trip Looking at Life and Death (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1987); Jane Howard, Margaret Mead, a Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984); Colin McPhee, A House in Bali (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979; orig. -

Religion and Belief in Higher Education: the Experiences of Staff and Students Equality Challenge Unit

Religion and belief in higher education: the experiences of staff and students Equality Challenge Unit This report was Acknowledgments researched and written by Professor Paul Weller of The team would like to thank colleagues in the International Centre for Guidance Studies, stakeholders, staff and students the Society, Religion and in the HEIs who supported and contributed to the project. Belief Research Group, Particular thanks go to Dr Kristin Aune, Lesley Gyford, Professor University of Derby, Dennis Hayes, Dr Phil Henry, Sukhi Kainth and Heather Morgan. and Dr Tristram Hooley and Nicki Moore of the The following organisations have provided ongoing support: International Centre = All-Party Parliamentary Group Against Antisemitism for Guidance Studies, = Church of England Board of Education University of Derby. = Community Security Trust = Federation of Student Islamic Societies = GuildHE = Higher Education Equal Opportunities Network = Hindu Forum of Britain = Inter Faith Network for the UK = National Federation of Atheist, Humanist and Secular Student Societies = National Hindu Students Forum = National Union of Students = Network of Buddhist Organisations (UK) = Student Christian Movement = Three Faiths Forum = UK Council for International Student Affairs = Union of Jewish Students = Universities UK = University and College Union = Young Jains Contact Chris Brill Dr Tristram Hooley [email protected] [email protected] Religion and belief in higher education: the experiences of staff and students Contents Executive summary 1 Recommendations -

The Importance of an Intersectional Perspective on Gendered Religious Persecution in International Law

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLI\61-2\HLI204.txt unknown Seq: 1 31-JUL-20 10:29 Volume 61, Number 2, Summer 2020 Suffering for Her Faith: The Importance of an Intersectional Perspective on Gendered Religious Persecution in International Law Isaac Conrad Herrera Sommers* Women around the world suffer from discriminatory treatment ranging from violent persecution to social differentiation. Likewise, religious people are routinely targeted because of their faith. Moreover, many women of faith have historically been and are still today subject to increased risk of harm or actually experience a greater level of targeted harm (as compared to non-religious women or religious men) because of the interplay between their religious and gender identities. Despite this, a number of the most prominent international legal institutions that deal directly with discrimination against women inade- quately use intersectional language to refer to religious women. In fact, there is a notable gap in scholar- ship and legal documents specifically addressing the disparate impact of discrimination toward religious women and a tendency to treat religion more as a source of oppression than as a distinct identity. Although many international organizations and agreements address issues of gender and religious discrimination separately, human rights bodies need to do more to address the intersection of gendered religious discrimina- tion. This Note is directed both at audiences who may be skeptical of or hostile toward intersectionality as a legal or policy framework, and at audiences who may support intersectionality but who are skeptical of or hostile toward religion. It addresses the importance of religious and gender identities and the ways those two identities are often inextricably linked. -

Human Rights Council Issue: Empowering Minority Religions Student Officer

th th The Hague International Model United Nations 2021| 25 January 2020 – 29 January 2020 Forum: Human Rights Council Issue: Empowering minority religions Student Officer: Anngu Chang Position: President Introduction The Violence Iceberg concept simplifies violence into two simple fields. The tip if the iceberg is explicit violence that is easy to witness, such as conflicts, discrimination, and terrorism. Addressing direct violence only requires short-term solutions that may temporarily alleviate and ease the violence but impart little to no impact, decreasing future violence chances. However, combating violence under the surface is the long-term solution that chips away at the root cause of conflict: our beliefs and decisions. Per the analogy, in the status quo, one of the most pressing icebergs that inhibit our path towards cultural cohesion is the lack of recognition and empowerment of minority religions. Such process is fundamental towards achieving a less conflict-driven world as clashes can be mitigated given appropriate dialogue and understanding. In such a religiously diverse world, empowering minority religions has presented itself as one of the iceberg roots the international community ought to tackle. Lack of recognition and representation serves as the root cause of why religious minorities seek empowerment: oftentimes, they are mute in international policies, and excluded in decisions over domestic laws and acts. Additionally, oppressed religious minorities are subjected to maltreatment and violence in a multitude of member states, and when met with violence, minorities may foster violent tendencies and actions of their own. The problem is not as visible as many think, and frequently intangibles such as stigmas and ingrained beliefs about members of minority religions prohibit conversations surrounding empowerment to even occur. -

Oman 2019 International Religious Freedom Report

OMAN 2019 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The Basic Law declares Islam to be the state religion but prohibits discrimination based on religion and protects the right of individuals to practice other religions as long as doing so does not “disrupt public order or contradict morals.” According to the law, offending Islam or any other Abrahamic religion is a criminal offense. There is no provision of the law specifically addressing apostasy, conversion, or renunciation of religious belief. Proselytizing in public is illegal. According to social media reports, in August police detained and brought in for questioning at least five individuals who had gathered to perform Eid al-Adha prayers a day before the official date announced by the Ministry of Endowments and Religious Affairs (MERA). MERA monitored sermons and distributed approved texts for all imams. Religious groups continued to report problems with opaque processes and unclear guidelines for registration. Nonregistered groups, such as The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Church of Jesus Christ) and others, remained without permanent, independent places of worship. Non-Muslim groups said they were able to worship freely in private homes and government-approved houses of worship, although space limitations continued to cause overcrowding at some locations. MERA continued to require religious groups to request approval before publishing or importing religious texts or disseminating religious publications outside their membership, although the ministry did not review all imported religious material. In September Catholic and Muslim leaders, including a senior MERA official, attended the inauguration of a new Catholic church in Salalah. In February the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) called on the government to remove a number of anti-Semitic titles being sold through the country’s annual state-run Muscat International Book Fair.