PUB TYPE Viewpoints (120)--Reports-Descriptive (141

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Actors' Stories Are a SAG Awards® Tradition

Actors' Stories are a SAG Awards® Tradition When the first Screen Actors Guild Awards® were presented on March 8, 1995, the ceremony opened with a speech by Angela Lansbury introducing the concept behind the SAG Awards and the Actor® statuette. During her remarks she shared a little of her own history as a performer: "I've been Elizabeth Taylor's sister, Spencer Tracy's mistress, Elvis' mother and a singing teapot." She ended by telling the audience of SAG Awards nominees and presenters, "Tonight is dedicated to the art and craft of acting by the people who should know about it: actors. And remember, you're one too!" Over the Years This glimpse into an actor’s life was so well received that it began a tradition of introducing each Screen Actors Guild Awards telecast with a distinguished actor relating a brief anecdote and sharing thoughts about what the art and craft mean on a personal level. For the first eight years of the SAG Awards, just one actor performed that customary opening. For the 9th Annual SAG Awards, however, producer Gloria Fujita O'Brien suggested a twist. She observed it would be more representative of the acting profession as a whole if several actors, drawn from all ages and backgrounds, told shorter versions of their individual journeys. To add more fun and to emphasize the universal truths of being an actor, the producers decided to keep the identities of those storytellers secret until they popped up on camera. An August Lineage Ever since then, the SAG Awards have begun with several of these short tales, typically signing off with his or her name and the evocative line, "I Am an Actor™." So far, audiences have been delighted by 107 of these unique yet quintessential Actors' Stories. -

Jon Stewart Hosts COMEDY CENTRAL's On-Air Charity Special

Jon Stewart Hosts COMEDY CENTRAL'S On-Air Charity Special 'Night Of Too Many Stars: An Overbooked Concert For Autism Education' With Live Wrap-Arounds From Los Angeles On Thursday, October 21 At 9:00 P.M. ET George Clooney, Tom Hanks, Jimmy Kimmel And Betty White Join The LA Live Star-Studded Event Special Segments With Conan O'Brien And Adam Sandler Added To Air In Telecast eBay Auction Featuring Numerous Celebrity Signed Items Now Available At www.comedycentral.com/stars With Bidding Ending On Monday, October 25 Donations Of Any Dollar Amount Accepted At www.comedycentral.com/stars A $10 Donation Can Be Made By Texting STARS To 90999 (Message and Data Rates May Apply) And Also Viewers Can Vote Via Texting On Stunts They Want To See Take Place During The LA Live Event Pepsi To Give An Additional $100,000 To The Top Three Most Voted Causes Selected By Viewers NEW YORK, Oct 19, 2010 /PRNewswire via COMTEX/ -- Over 50 amazing performers will show their support and lend their comedy chops to "Night Of Too Many Stars: An Overbooked Concert For Autism Education," the biennial/bi-coastal event which raises funds to help ease the severe shortage of effective schools and education programs for autistic children and adults. This year's presentation features star-studded taped segments from the Beacon Theatre in New York City with additional live wrap-arounds from Los Angeles including a celebrity phone bank which allows viewers to call in during the show to donate while speaking with additional comedic heavyweights. Stewart hosts an evening filled with live performances and sketches from a roster of comedy all-stars with live wrap-arounds in LA and showcasing the taped segments from New York City which premieres on COMEDY CENTRAL on Thursday, October 21 at 9:00 p.m. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 88Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 88TH ACADEMY AWARDS ADULT BEGINNERS Actors: Nick Kroll. Bobby Cannavale. Matthew Paddock. Caleb Paddock. Joel McHale. Jason Mantzoukas. Mike Birbiglia. Bobby Moynihan. Actresses: Rose Byrne. Jane Krakowski. AFTER WORDS Actors: Óscar Jaenada. Actresses: Marcia Gay Harden. Jenna Ortega. THE AGE OF ADALINE Actors: Michiel Huisman. Harrison Ford. Actresses: Blake Lively. Kathy Baker. Ellen Burstyn. ALLELUIA Actors: Laurent Lucas. Actresses: Lola Dueñas. ALOFT Actors: Cillian Murphy. Zen McGrath. Winta McGrath. Peter McRobbie. Ian Tracey. William Shimell. Andy Murray. Actresses: Jennifer Connelly. Mélanie Laurent. Oona Chaplin. ALOHA Actors: Bradley Cooper. Bill Murray. John Krasinski. Danny McBride. Alec Baldwin. Bill Camp. Actresses: Emma Stone. Rachel McAdams. ALTERED MINDS Actors: Judd Hirsch. Ryan O'Nan. C. S. Lee. Joseph Lyle Taylor. Actresses: Caroline Lagerfelt. Jaime Ray Newman. ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS: THE ROAD CHIP Actors: Jason Lee. Tony Hale. Josh Green. Flula Borg. Eddie Steeples. Justin Long. Matthew Gray Gubler. Jesse McCartney. José D. Xuconoxtli, Jr.. Actresses: Kimberly Williams-Paisley. Bella Thorne. Uzo Aduba. Retta. Kaley Cuoco. Anna Faris. Christina Applegate. Jennifer Coolidge. Jesica Ahlberg. Denitra Isler. 88th Academy Awards Page 1 of 32 AMERICAN ULTRA Actors: Jesse Eisenberg. Topher Grace. Walton Goggins. John Leguizamo. Bill Pullman. Tony Hale. Actresses: Kristen Stewart. Connie Britton. AMY ANOMALISA Actors: Tom Noonan. David Thewlis. Actresses: Jennifer Jason Leigh. ANT-MAN Actors: Paul Rudd. Corey Stoll. Bobby Cannavale. Michael Peña. Tip "T.I." Harris. Anthony Mackie. Wood Harris. David Dastmalchian. Martin Donovan. Michael Douglas. Actresses: Evangeline Lilly. Judy Greer. Abby Ryder Fortson. Hayley Atwell. ARDOR Actors: Gael García Bernal. Claudio Tolcachir. -

Page 1 1 ALL in the FAMILY ARCHIE Bunker Emmy AWARD

ALL IN THE FAMILY ARCHIE Bunker Based on the British sitcom Till MEATHEAD Emmy AWARD winner for all DEATH Us Do Part MIKE Stivic four lead actors DINGBAT NORMAN Lear (creator) BIGOT EDITH Bunker Archie Bunker’s PLACE (spinoff) Danielle BRISEBOIS FIVE consecutive years as QUEENS CARROLL O’Connor number-one TV series Rob REINER Archie’s and Edith’s CHAIRS GLORIA (spinoff) SALLY Struthers displayed in Smithsonian GOOD Times (spinoff) Jean STAPLETON Institution 704 HAUSER (spinoff) STEPHANIE Mills CHECKING In (spinoff) The JEFFERSONS (spinoff) “STIFLE yourself.” “Those Were the DAYS” MALAPROPS Gloria STIVIC (theme) MAUDE (spinoff) WORKING class T S Q L D A H R S Y C V K J F C D T E L A W I C H S G B R I N H A A U O O A E Q N P I E V E T A S P B R C R I O W G N E H D E I E L K R K D S S O I W R R U S R I E R A P R T T E S Z P I A N S O T I C E E A R E J R R G M W U C O G F P B V C B D A E H T A E M N F H G G A M A L A P R O P S E E A N L L A R C H I E M U L N J N I O P N A M R O N Z F L D E I D R E D O O G S T I V I C A E N I K H T I D E T S A L L Y Y U A I O M Y G S T X X Z E D R S Q M 1 84052-2 TV Trivia Word Search Puzzles.indd 1 10/31/19 12:10 PM THE BIG BANG THEORY The show has a science Sheldon COOPER Mayim Bialik has a Ph.D. -

The Not-So-Spectacular Now by Gabriel Broshy

cinemann The State of the Industry Issue Cinemann Vol. IX, Issue 1 Fall/Winter 2013-2014 Letter from the Editor From the ashes a fire shall be woken, A light from the shadows shall spring; Renewed shall be blade that was broken, The crownless again shall be king. - Recited by Arwen in Peter Jackson’s adaption of the final installment ofThe Lord of the Rings Trilogy, The Return of the King, as her father prepares to reforge the shards of Narsil for Ara- gorn This year, we have a completely new board and fantastic ideas related to the worlds of cinema and television. Our focus this issue is on the states of the industries, highlighting who gets the money you pay at your local theater, the positive and negative aspects of illegal streaming, this past summer’s blockbuster flops, NBC’s recent changes to its Thursday night lineup, and many more relevant issues you may not know about as much you think you do. Of course, we also have our previews, such as American Horror Story’s third season, and our reviews, à la Break- ing Bad’s finale. So if you’re interested in the movie industry or just want to know ifGravity deserves all the fuss everyone’s been having about it, jump in! See you at the theaters, Josh Arnon Editor-in-Chief Editor-in-Chief Senior Content Editor Design Editors Faculty Advisor Josh Arnon Danny Ehrlich Allison Chang Dr. Deborah Kassel Anne Rosenblatt Junior Content Editor Kenneth Shinozuka 2 Table of Contents Features The Conundrum that is Ben Affleck Page 4 Maddie Bender How Real is Reality TV? Page 6 Chase Kauder Launching -

Actors' Stories Are a SAG Awards® Tradition Over the Years an August Lineage

Actors' Stories are a SAG Awards® Tradition When the first Screen Actors Guild Awards® were presented on March 8, 1995, the ceremony opened with a speech by Angela Lansbury introducing the concept behind the SAG Awards and the Actor® statuette. During her remarks she shared a little of her own history as a performer: "I've been Elizabeth Taylor's sister, Spencer Tracy's mistress, Elvis' mother and a singing teapot." She ended by telling the assembled audience of SAG Awards nominees and presenters, "Tonight is dedicated to the art and craft of acting by the people who should know about it: actors. And remember, you're one too!" Over the Years This glimpse into an actor’s life was so well received that it began a tradition of beginning each Screen Actors Guild Awards with a distinguished actor relating a brief anecdote and sharing thoughts about what the art and craft mean on a personal level. For the first eight years of the SAG Awards, just one actor performed that customary opening. For the 9th Annual SAG Awards, however, producer Gloria Fujita O'Brien suggested a twist. She observed it would be more representative of the acting profession as a whole if several actors, drawn from all ages and backgrounds, told shorter versions of their individual journeys. To add more fun and to emphasize the universal truths of being an actor, the producers decided to keep the identities of those storytellers secret until they popped up on camera. An August Lineage Ever since then, the SAG Awards have begun with several of these short tales, typically signing off with his or her name and the evocative line, "I’m an Actor." So far audiences have been delighted by 78 of these unique yet quintessential Actors' Stories. -

Emmy Award Winners

CATEGORY 2035 2034 2033 2032 Outstanding Drama Title Title Title Title Lead Actor Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actress—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Outstanding Comedy Title Title Title Title Lead Actor—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actress—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Outstanding Limited Series Title Title Title Title Outstanding TV Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actor—L.Ser./Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—L.Ser./Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—L.Ser./Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actress—L.Ser./Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title CATEGORY 2031 2030 2029 2028 Outstanding Drama Title Title Title Title Lead Actor—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actress—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Outstanding Comedy Title Title Title Title Lead Actor—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. -

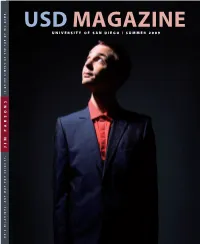

Usd Magazine University of San Diego / Summer 2009 Is Quite Simply at the Top of His Game

USD MAGAZINE UNIVERSITY OF SAN DIEGO / SUMMER 2009 IS QUITE SIMPLY AT THE TOP OF HIS GAME. IS QUITE SIMPLY AT THE TOP OF HIS GAME. JIM PARSONS FALL 2005 B HE’S HILARIOUS: ANY WAY YOU SLICE IT, HE’S HILARIOUS: ANY WAY YOU SLICE IT, FROM THE PRESIDENT [priorities] LOOKING FORWARD An update on the university’s financial condition emaining optimistic during times of economic constraint and uncertainty can be a challenge, particularly when their impact on people and programs cannot be fully anticipated. USD has persevered and prospered R despite serious challenges throughout its history because of the talent, creativity, hard work and cooperation of the truly dedicated faculty, administrators and staff who are among our institution’s greatest resources. To thrive during these times, it is important to keep current challenges in perspective; USD’s spring enrollments are normal and undergraduate applications for next fall are up slightly. In addition, we are currently able to main- tain our present level of financial aid commitments to our students. Also, unlike many other universities, we are not considering personnel reductions at this time. The university’s 2009-2010 budget has been formally approved by our trustees to include our primary commit- ments to financial aid, infrastructure renewal, sustaining faculty and staff levels, and academic program support. The trustees also reviewed our budget projections for the remainder of the current fiscal year. They endorsed our call for fiscal restraint and acknowledged that uninterrupted academic programs and student services remain our first institutional priority. Consistent with our core values, we are foremost concerned about the well-being of the people in our university community. -

JAN 1 3 2015 of the City of Los Angeles

ACCELERATED REVIEW PROCESS - E Office of the City Engineer Los Angeles California To the Honorable Council JAN 1 3 2015 Of the City of Los Angeles Honorable Members: C. D. No. 13 SUBJECT: Hollywood Boulevard and Vine Street- Walk of Fame Additional Name in Terrazzo Sidewalk DICK GREGORY RECOMMENDATIONS: A. That the City Council designate the unnumbered location situated one sidewalk square easterly of and between numbered locations 11r and 11R as shown on Sheet #22 of Plan D-13788 for the Hollywood Walk of Fame for the installation of the name of Dick Gregory at 1650 Vine Street. B. Inform the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce ofthe Council's action on this matter. C. That this report be adopted prior to the date of the ceremony on February 2, 2015. FISCAL IMP ACT STATEMENT: No General Fund Impact. All cost paid by permittee. TRANSMITTALS: 1. Unnumbered communication dated January 7, 2015, from the Hollywood Historic Trust of the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce, biographical information and excerpts from the minutes of the Chamber's meeting with recommendations. City Council - 2 - C. D. No. 13 DISCUSSION: The Walk of Fame Committee of the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce has submitted a request for insertion into the Hollywood Walk of Fame the name of Dick Gregory. The ceremony is scheduled for Monday, February 2, 2015 at 11:30 a.m. The communicant's request is in accordance with City Council action of October 18, 1978, under Council File No. 78-3949. Following the Council's action of approval, and upon proper application and payment of the required fee, an installation permit can be secured at 201 N. -

Movie Data Analysis.Pdf

FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM COGS108 Final Project Group Members: Yanyi Wang Ziwen Zeng Lingfei Lu Yuhan Wang Yuqing Deng Introduction and Background Movie revenue is one of the most important measure of good and bad movies. Revenue is also the most important and intuitionistic feedback to producers, directors and actors. Therefore it is worth for us to put effort on analyzing what factors correlate to revenue, so that producers, directors and actors know how to get higher revenue on next movie by focusing on most correlated factors. Our project focuses on anaylzing all kinds of factors that correlated to revenue, for example, genres, elements in the movie, popularity, release month, runtime, vote average, vote count on website and cast etc. After analysis, we can clearly know what are the crucial factors to a movie's revenue and our analysis can be used as a guide for people shooting movies who want to earn higher renveue for their next movie. They can focus on those most correlated factors, for example, shooting specific genre and hire some actors who have higher average revenue. Reasrch Question: Various factors blend together to create a high revenue for movie, but what are the most important aspect contribute to higher revenue? What aspects should people put more effort on and what factors should people focus on when they try to higher the revenue of a movie? http://localhost:8888/nbconvert/html/Desktop/MyProjects/Pr_085/FinalProject.ipynb?download=false Page 1 of 62 FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM Hypothesis: We predict that the following factors contribute the most to movie revenue. -

The 63R D Primetime Emmy Awards

TV THE 63 RD PRIMETIME EMMY AWARDS Drama Series Supporting Actor in a Reality-Competition Program Miniseries or Movie Boardwalk Empire Drama Series BThe Amazing Race Mildred Pierce Dexter Andre Braugher, Men of a Certain Age American Idol Downton Abbey (Masterpiece) Friday Night Lights Alan Cumming, The Good Wife Dancing with the Stars The Kennedys Game of Thrones Josh Charles, The Good Wife Project Runway Cinema Verite The Good Wife Peter Dinklage, Game of Thrones So You Think You Can Dance Too Big To Fail Mad Men Walton Goggins, Justified Top Chef The Pillars Of The Earth John Slattery, Mad Men Comedy Series Supporting Actor in a Reality Program Lead Actor in a Miniseries The Big Bang Theory Comedy Series Hoarders or Movie Glee Ty Burrell, Modern Family Antiques Roadshow Greg Kinnear, The Kennedys Modern Family Jon Cryer, Two and a Half Men Deadliest Catch Barry Pepper, The Kennedys The Office Chris Colfer, Glee MythBusters Edgar Ramirez, Carlos Parks and Recreation Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Modern Family Undercover Boss William Hurt, Too Big To Fail 30 Rock Ed O'Neill, Modern Family Kathy Griffin: My Life on the D-List Idris Elba, Luther Eric Stonestreet, Modern Family Laurence Fishburne, Thurgood Lead Actor in a Drama Series Supporting Actress in a Host for a Reality or Lead Actress in a Miniseries Steve Buscemi, Boardwalk Empire Drama Series Reality-Competition Program or Movie Kyle Chandler, Friday Night Lights Christine Baranski, The Good Wife Tom Bergeron, Dancing with the Stars Kate Winslet, Mildred Pierce Michael C. Hall, Dexter Michelle Forbes, The Killing Cat Deeley, So You Think You Can Dance Elizabeth McGovern, Downton Abbey Jon Hamm, Mad Men Christina Hendricks, Mad Men Phil Keoghan, The Amazing Race Diane Lane, Cinema Verite Hugh Laurie, House Kelly Macdonald, Boardwalk Empire Jeff Probst, Survivor Taraji P. -

Sundance 2019

SUNDANCE 2019 TOP 10 MOST ANTICIPATED FILMS Photo by Erwin More EXTREMELY WICKED, Writer: Michael Werwie SHOCKINGLY EVIL AND VILE Director: Joe Berlinger Producers: Michael Costigan, Nicolas Chartier, Ara Keshishian, 108 minutes Michael Simkin Executive Producers: Jason Barrett, Jonathan Deckter, Michael A chronicle of the crimes of Ted Bundy from the perspective of Werwie Liz, his longtime girlfriend, who refused to believe the truth Starring: Zac Efron, Lily Collins, Kaley Joel Osment, Kaya about him for years. Scodelario, John Malkovich, Jim Parsons More-Medavoy Management Sundance 2019 THE FARWELL Writer/Director: Lulu Wang 98 minutes Producers: Daniele Melia, Peter Saraf, Marc Turtletaub, Andrew Miano, Chris Weitz, Jane Zheng, Lulu Wang, Anita Gou A Chinese family discover their grandmother has only a short Executive Producers: Jason Barrett, Jonathan Deckter, Michael while left to live and decide to keep her in the dark, scheduling Werwie a wedding to gather before she dies. Starring: Awkwafina, Tzi Ma, Diana Lin, Jim Liu, Shuzhen Zhou, Ines Laimins, Gil Perez-Abraham More-Medavoy Management Sundance 2019 HONEY BOY Writer: Shia LaBeouf 93 minutes Director: Alma Har'el Producers: Brian Kavanaugh-Jones, Daniela Taplin Lundberg, A child actor works to mend the relationship with his Anita Gou, Christopher Leggett, Alma Har'el hard-drinking, law-breaking father. Starring: Shia LaBeouf, Lucas Hedges, Noah Jupe, FKA Twigs, Laura San Giacomo, Maika Monroe, Natasha Lyonne, Clifton Collins Jr., Martin Starr More-Medavoy Management Sundance 2019 LATE NIGHT Writer: Mindy Kaling 102 minutes Director: Nisha Ganatra Producers: Mindy Kaling, Howard Klein, Ben Browning, Jillian A late-night talk show host suspects that she may soon be Apfelbaum losing her long-running show.