Horizontal Merger Guidelines Review Project 6 7 8 Tuesday, December 8, 2009 9 9:05 A.M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 the RING of the DOVE by IBN HAZAM

THE RING OF THE DOVE By IBN HAZAM (994-1064) A TREATISE ON THE ART AND PRACTICE OF ARAB LOVE Translated by A.J. ARBERRY, LITT.D., F.B.A LUZAC & COMPANY, LTD. 46 GREAT RUSSELL STREET, LONDON, W.C. 1 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- CONTENTS -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Preface Author's Preface Preliminary Excursus The Signs Of Love On Falling In Love While Asleep On Falling In Love Through A Description On Falling In Love At First Sight On Falling In Love After Long Association On Falling In Love With A Quality And Thereafter Not Approving Any Other Different Of Allusion By Words Of Hinting With The Eyes Of Correspondence Of The Messenger Of Concealing The Secret Of Divulging The Secret Of Compliance Of Opposition Of The Reproacher Of The Helpful Brother Of The Spy Of The Slanderer Of Union Of Breaking Off Of Fidelity Of Betrayal Of Separation Of Contentment Of Wasting Away Of Forgetting Of Death 1 Of The Vileness Of Sinning Of The Virtue Of Continence PREFACE THE Arabs carrying Islam westwards to the Atlantic Ocean first set foot on Spanish soil during July 710 the leader of the raid, which was to prove the forerunner of long Moslem occupation of the Iberian Peninsula, was named Tarif, and the promontory on which he landed commemorates his exploit by being called to this day Tarifa. The main invasion followed a year later; Tariq Ibn Ziyad, a Berber by birth, brought over from the African side of the narrows a comparatively small army which sufficed to overthrow Roderick the Visigoth and to supplant the Cross by the Crescent; he gave his name to that famous Rock of Gibraltar (Jabal Tariq, the Mountain of Tariq), which has been disputed by so many conquerors down the ages, and over which the British flag has fluttered since the early years of the eighteenth century. -

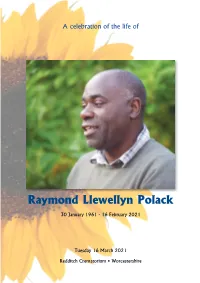

Order of Service Raymond Polack

A celebration of the life of Raymond Llewellyn Polack 30 January 1961 - 16 February 2021 Tuesday 16 March 2021 Redditch Crematorium • Worcestershire Opening Music You Are the Sunshine of My Life Stevie Wonder Lovely Day Bill Withers Welcome Sarah Bertram, Funeral Celebrant Poem Death Is Not the End Peter Tatchell Death is not the end But the beginning Of a metamorphosis. For matter is never destroyed, Only transformed And rearranged – Often more perfectly. Witness how in the moment of the caterpillar’s death The beauty of the butterfly is born And released from the prison of the cocoon It flies free. Tribute Lloyd Polack, Raymond's twin brother We just had our birthday. Made it to 60, we did - good innings! Jazz is filled with mirrors reflecting off of one another - take a mis-step and go with it, develop a new groove.You and I, Raymond, as kids we were one another's mirror.We couldn't get more close - being each other's twin brother. We entered the children's home on Packington Avenue when four, after a year or so on a farm till one of us got sick, which one I don't know. We were named as 'the twins' when together, or when spoken to individually merely 'twin'.Together we had good times there, four meals a day, four holidays each year! And kids in our children's home were treated to fantastic Christmases, Mrs. Morgan was a great chef. Before leaving the home you and I were the Birmingham Boys' Club table tennis doubles champions, I wonder if anyone might have a photo of us as fifteen year-old champions lifting the Champion's Cup? We found out only years later, at one point when we were about five, they had thought to split us up. -

Grassroots Post-Modernism Is Daring in Its Thesis That the Real Postmodernists Are to Be Found Among the Zapotecos and Rajasthanis of the Majority World

Grassroots Post-Modernism Remaking the soil of cultures Gustavo Esteva & Madhu Suri Prakash i 'Beyond its definite "No" to the Global Project, this book takes a stimulating glance at the renewed life of social majorities and offers good reasons for a common hope! GILBERT RIST 'Grassroots Post-modernism is daring in its thesis that the real postmodernists are to be found among the Zapotecos and Rajasthanis of the majority world. It is hard-hitting in its attacks against progressive commonplaces, like global responsibility, human rights, the autonomy of the individual, and democracy. And it is eye-opening in its illustrations of how ordinary people, amidst the rubble of the development epoch, stitch their cultural fabric together and unwittingly move beyond the impasse of modernity.' WOLFGANG SACHS 'Esteva and Prakash courageously and clear-sightedly take on some of the most entrenched of modern certainties such as the universality of human rights, the individual self, and global thinking. In their efforts to remove the lenses of modernity that education has bequeathed them, they dig deep into their own encounters with what they call the "social majorities" in their native Mexico and India. There they see not an enthralment with the seductions of modernity but evidence of a will to live in their own worlds according to their own lights. Esteva's and Prakash's reflections on the imperialism of the universality of human rights avoids the twin pitfalls of relativism and romanticism. Their alternative is demanding and novel, and deserves our most serious consideration. Grassroots Post-modernism is a much needed and most welcome counterpoint both to the nihilism of much post-modern thinking as well as to those who view the spread of the global market and of global thinking too triumphantly.' FREDERIQUE APFFEL-MARGLIN 'Quite simply, a book which will transform how one sees the world.’ NORTH AND SOUTH ii iii ABOUT THE AUTHORS GUSTAVO ESTEVA is one of Latin America's most brilliant intellectuals and a leading critic of the development paradigm. -

Physical Activity Kit (PAK) Overview

Table of Contents Table of Contents................................................................................................................................. 1 Physical Activity Kit (PAK) Overview ................................................................................................... 3 Introduction to PAK Books ................................................................................................................... 4 Healthy Physical Activity for Young Children .................................................................................... 5-6 Safety Recommendations and Tips .................................................................................................. 7-8 Physical Fitness for Infants, Toddlers and Preschoolers ................................................................ 9-10 Guidelines For Indoor/Outdoor Play Areas ................................................................................... 11-12 15 Simple and Easy Ways to Get Moving.......................................................................................... 13 PHYSICAL ACTIVITY GUIDE ............................................................................................................ 15 Developmentally Appropriate Physical Activities For Young Children ....... …………………………16-26 Outdoor Play Activities………………………….............................................................................. 27-31 Choosy Kids................................................................................................................................. -

NSB Daniel Im-Foreword Ch1.Pdf

While discipling others who will then disciple others is Jesus’ master plan, defining maturity is sometimes tricky. I’m grateful that Daniel outlines a research-based, yet practical way, to understand and move people toward Christlikeness. Don’t miss this. Robert E. Coleman, distinguished senior professor of Evangelism and Discipleship, Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary Daniel Im is a brilliant young thought leader who in No Silver Bullets offers hope to every leader by showing us five micro shifts that can bring macro changes in our churches. This book is a reality check reminding us quick fixes will not bring lasting change; but a change in perspective can usher in a new day. If you are done with easy solutions and ready for a clear path to lasting change this is the book for you! Dave Ferguson, lead pastor of Community Christian Church and author of Finding Your Way Back to God and Starting Over No Silver Bullets is as good a read as the title is honest. Finally a new, young voice enters the fray with clear thinking, rational conclusions, and a radical call. I felt lit up, called out, and calmed down all at the same time. Hugh Halter, US Director of Forge America and author of The Tangible Kingdom and Flesh While God will complete in us the good work that He began, there are no silver bullets in our spiritual growth. And there are no silver bullets in dis- cipling and shepherding a church. There are, however, important perspec- tives we may adopt that will greatly impact how we lead and the direction and development of those we lead. -

Help Your Faith Community Deepen and Expand Their Welcome to People of All Sexual Orientations, Gender Identities, and Gender Expressions

Help your faith community deepen and expand their welcome to people of all sexual orientations, gender identities, and gender expressions. 1 Building an Inclusive Church COMMUNITY PEOPLE WELCOME FAITH JOURNEY CHURCH GENDER LGBTQIA+ WORK PERSON STORY AFFIRM TIME TEAM IDENTITY STEP CHANGE LIFE VISIT ENGAGE FRAME CONGREGATION SCRIPTURE ORIENTATION ASK HELP QUESTION RELATIONSHIP SHARE JUSTICE UNDERSTAND GOD COMMUNITY PEOPLE WELCOME FAITH JOURNEY CHURCH GENDER LGBTQIA+ WORK PERSON STORY AFFIRM TIME TEAM IDENTITY STEP CHANGE LIFE VISIT ENGAGE FRAME CONGREGATION SCRIPTURE ORIENTATION ASK HELP QUESTION RELATIONSHIP SHARE JUSTICE UNDERSTAND GOD COMMUNITY PEOPLE WELCOME FAITH JOURNEY CHURCH GENDER LGBTQIA+ WORK PERSON STORY AFFIRM TIME TEAM IDENTITY STEP CHANGE LIFE VISIT ENGAGE FRAME CONGREGATION SCRIPTURE ORIENTATION ASK HELP QUESTION RELATIONSHIP SHARE JUSTICE UNDERSTAND GOD COMMUNITY PEOPLE WELCOME FAITH JOURNEY CHURCH GENDER LGBTQIA+ WORK PERSON STORY AFFIRM TIME TEAM IDENTITY STEP CHANGE LIFE VISIT ENGAGE FRAME CONGREGATION SCRIPTURE ORIENTATION ASK HELP QUESTION RELATIONSHIP SHARE JUSTICE UNDERSTAND GOD COMMUNITY PEOPLE WELCOME FAITH JOURNEY CHURCH GENDER LGBTQIA+ WORK PERSON STORY AFFIRM TIME TEAM IDENTITY STEP CHANGE LIFE VISIT ENGAGE FRAME CONGREGATION SCRIPTURE ORIENTATION ASK HELP QUESTION RELATIONSHIP SHARE JUSTICE UNDERSTAND GOD COMMUNITY PEOPLE WELCOME FAITH JOURNEY CHURCH GENDER LGBTQIA+ WORK PERSON STORY AFFIRM TIME TEAM IDENTITY STEP CHANGE LIFE VISIT ENGAGE FRAME CONGREGATION SCRIPTURE ORIENTATION ASK HELP QUESTION RELATIONSHIP -

On Becoming a Leader.Pdf

0465014088_fm.qxd:0738208175_fm.qxd 12/2/08 2:52 PM Page i More praise for On Becoming a Leader “Warren Bennis—master practitioner, researcher, and theoretician all in one—has managed to create a practical primer for leaders without sacrificing an iota of necessary subtlety and complexity. No topic is more important; no more able and caring person has attacked it.” —Tom Peters “The lessons here are crisp and persuasive.” —Fortune “This is Warren Bennis’s most important book.” —Peter Drucker “A joy to read...studded with gems of insight.” —Dallas Times-Herald “Bennis identifies the key ingredients of leadership success and offers a game plan for cultivating those qualities.” —Success “Clearly Bennis’s best work in a long line of impressive, significant contributions.” —Business Forum “Totally intriguing, thought-stretching insights into the clockworks of leaders. Bennis has masterfully peeled the onion to reveal the heartseed of leadership. Read it and reap.” —Harvey B. McKay “Warren Bennis gets to the heart of leadership, to the essence of integrity, authenticity, and vision that can never be pinned down to a manipulative formula. This book can help any of us select the new leaders we so urgently need.” —Betty Friedan “Warren Bennis’s insight and his gift with words make these lessons, from some of America’s most interesting leaders, compelling reading for every executive.” —Charles Handy 0465014088_fm.qxd:0738208175_fm.qxd 12/2/08 2:52 PM Page ii This page intentionally left blank 0465014088_fm.qxd:0738208175_fm.qxd 12/2/08 2:52 PM Page -

Home Study Course Development Handbook

DOM! V? RESUME iD 103 943 (CE 024 §72, AUTHOR Laibertti.chacl, Welch, ,S:arly B. TITLE Home" StudV CO$rse Development Handbook. 'INSTITUTION ,National Home, Study CouncilVshington, D.C. PUB. DATE 30. ,NOTE 256p:* AVAILAtLE FROM'National Home Study. council, 1601 18t,h Street, DC ,2000,9(15..00) EDRS MF01/PC11--Plu_s Postage. ,DESCRIPTORS Accoustin;i: Adult 'Education': AudioviSAl Aids: Authors: *CorresPomdenee Study: CoursIklitntent; t vi CourA Ob lectivds : Course 4: *Curricul uui *Curriculum Develoilher;t: Editing; *Home' Study: Material Develcpm-enf: Multiple Choice Tests; Readability Formulas: *Test Construction: Trextbook T:treparation: #Textbook Publication , ABSTRACT . - Intended for independent 'stud y directors: course authors, And'directors of hombased or dis,tance learaingrojects,:: thisollettion 'of current, practical guides on cotrespon den,qe course deva p1$rent contains fourteen, chapters authorel by practicing'ik9'me stuelducatorsd, and experts in their field. From Theory to Pract'i .liSts stays in course produdtion from subject "selection thzough revision grogram implementation. 4 Naming the Parts lists course Ompottents with. a profile of a home study oou.:Tse and glossary ; included. Approaching Course Development offers guidpIce on pla:kaing. -'Supervising .COurse Authors discusses author selection mid* gives x 'sample author' s contract. Writing Oblectives shows how to prepare good- instructional objectives.(A rev itw quiz follows.) Working lagic.. with manuscripts provides checklists for copy editing.' Managing Text Readability discusses reading level fcriaufas4 and Orovides practice j examples.txhe Dale list of 30,000 Familiar Words is appended.) Writing Examples uses practical exatnras in describing multiple -- .choice test preparation. Audlo Visuat Material ftsc'usses their pffective use. -

Arashi Album)

Here We Go! (Arashi album) 01. Kansha Kangeki Ame Arashi 02. OK! ALL RIGHT! ii Koi wo Shiyou 03. Kansha Kangeki Ame Arashi (Original Karaoke) 04. OK! ALL RIGHT! ii Koi wo Shiyou (Original Karaoke) UT. ARASHI No.1 ~Arashi wa Arashi wo Yobu~ [Album] (24.01.2001). 01. Tomadoi Nagara (album version) 02. Canâ™t Let You Go (Vocal: Sho Sakurai) 05. Yabai-Yabai-Yabai (Vocal: Jun Matsumoto) UT Step and Go [Single] (20.02.2008). 01. Step and Go 02. Fuyu wo Dakishimete 03. Step and Go (Original Karaoke) 04. Fuyu wo Dakishimete (Original Karaoke) UT Dream''A''live [Album] (23.04.2008). CD 1 01. theme of DreamâAâlive 02. J Storm Official Site Arashi Discography Album. ãŒuntitledã. Arashi. Album - 2017.10.18. Are You Happy? Arashi. Album - 2016.10.26. Japonism. Arashi. Album - 2015.10.21. The digitalian. Arashi. Album - 2014.10.22. Love. Arashi. Album - 2013.10.23. Popcorn. Arashi. Album - 2012.10.31. Beautiful World. Arashi. Album - 2011.07.06. 僕ã®è¦‹ã¦ã„る風景. Arashi. Album - 2010.08.04. ARASHI 5×10 All the BEST! 1999-2009. Arashi. Album - 2009.08.19. Dream"A"live. Arashi. Album - 2008.04.23. Time. Arashi. Album - 2002.10.30. Here we go! Arashi. Album - 2002.07.17. ARASHI DISCOGRAPHY (Album). I'm sorry but I won't reupload anything anymore. The links that works, works, the ones that are broken are gone forever. Please, don't ask me to reupload :) 1) I don't share other files (but someone asked me to add their files to this collection) 2) To copy my CD, to scan, to upload (mediafire) and re-upload (filecloud) took a lot of time, so please respect my work ^^ 3) I still haven't completed my collection, so I don't have ALL the CDs or ALL the RE/LE. Here We Go! [RE] Download DISC Download SCAN. -

DI Presses in the In-Plant

DIDI PressesPresses inin thethe In-plantIn-plant ScoresScores of of in-plantsin-plants are are installinginstalling directdirect imagingimaging (DI)(DI) offset offset presses.presses. WhyWhy do do theythey feel feel DIDI technology technology isis so so well well A brandA brand new new Presstek Presstek 52DI 52DI was was just just installed installed at at GlasgowGlasgow Caledonian Caledonian University, University, in Scotland.in Scotland. With With it hereit here are are suitedsuited to to (from(from the the left): left): Andrew Andrew Scott, Scott, head head of Printof Print Design Design Services; Services; theirtheir mix mix of of StevenSteven McCart, McCart, print print production production manager; manager; Colin Colin Gaffney, Gaffney, offset offset work?work? printprint operator; operator; and and Karen Karen Kernan, Kernan, offset offset print print operator. operator. ByBy Bob Bob Neubauer Neubauer EVENEVEN AFTER AFTER installing installing an anHP HP Indigo Indigo 1050 1050 recentrecent years, years, viewing viewing it asit asa cost-effective a cost-effective way way digitaldigital color color press press four four years years ago, ago, San San Diego Diego to toenter enter the the four-color four-color market. market. StateState University University ReproGraphic ReproGraphic Services Services still still ThatThat was was the the case case at atCalifornia California State State Poly Poly- - foundfound it challengingit challenging to toreach reach portions portions of ofthe the technictechnic University, University, in inPomona, -

Issue 4 -D Dec 2020 Editors Letter

Issue 4 -D Dec 2020 Editors Letter SulSul Simmers, Welcome to issue 7 of SimmedUp Magazine. This month we come together to celebrate Mothers Day but here at SimmedUp we dedicate this issue to all families, so whether you be a blended, foster, adoptive or one of the many other types of family units out there, this month is for you. Featuring LittleMsSams Baby Scan Mod review by Grace, The Breastfeeding Pose Pack is reviewed by maria with some stunning imagery. We also have ‘How to create CC Floors’ to help decorate the family home your way By A.Muller from ExtraTimeMedia and Grannys Comfort Soup in Cooking Sims style. This month we also bring you the all new Simtography with Minraed and #MachinimaLife for the budding director out there by our very own TheMomCave. Not forgetting our Interviewees this month we have the fabulous Kamila Interviewed by Sue and The enchanting Alexis Creator of SIMS VIP. So whatever your doing this month, if you manage to see your families in person or not, make sure to let your family know you care and pick up the phone, send a text message or email. So from one family to another Happy Mother’s/Family Day to you all, no matter where you are. Benzi chibna looble bazebni gweb SimSimmerly On The Sims Resource 60INTERVIEW: KAMILA 68 YOUR SIMS: SHOWCASING YOUR SIMS 72 LOVE TO SHOP: EXCLUSIVE MERCH & CC 76 BUILD A BETTER LIFE: WITH THE MOM CAVE 82 SIMSPIRATION: WITH K8SIMSLEY 90 SIMTOGRAPHY: PHOTOGRAPHY TIPS WITH MINRAED 96 MAKING A SIMMER: KAWAII FOXITA 102SIMSCOPES: WHAT DO THE SIMS STARS 36 CUSTOM CONTENT: HOLD IN STORE FOR YOU? HOW TO MAKE CC FLOORS 42 TITAN ARCHITECTS: #SHOWUSYOURBUILDS. -

Miwam Toolkit for Claimants Revised: October 30, 2018 1

Michigan Web Account Manager Unemployment Insurance For Claimants MiWAM Toolkit for Claimants Revised: October 30, 2018 1 Q: What happens when I register for MiWAM? A: When you register for MiWAM, you will be granted unlimited access to your MiWAM account immediately. You can access your account 24 hours a day, seven days a week. MILogin for Citizens is a single sign on process that connects you to MiWAM and Pure Michigan Talent Connect systems. Q: Does my password expire? A: Yes, your password expires every 13 months. As a result, you will be required to change it after one year. Q: What should I do if I forget my username or need to reset my password? A: Click on the hyperlinks “Forgot your User ID?” or “Forgot your password?” You can use the automatic functions regarding a forgotten User ID and/or password the majority of the time. Both User ID and password automatic recovery processes use the Security Option(s) that you chose during the MILogin registration process. If you need further assistance, contact 1-866-500-0017 to speak with a customer service representative. Q: Can I come back to a claim that I began filing and finish it later? A: MiWAM allows you to save your claim and complete it later during the same calendar week, by clicking the Save and finish later button. You will receive a confirmation number and a claim filing number. Click the “Find a Saved Claim” hyperlink to complete the claims filing process before 11:59 PM on Saturday so your claim will be considered timely.