Masters 0 2 7 1 0 0 D D C C R R H H C C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey College Birmingham 873/4603 Abbey College, Ramsey Ramsey 865/4000 Abbeyfield School Chippenham 803/4000 Abbeywood Community School Bristol 860/4500 Abbot Beyne School Burton-on-Trent 312/5409 Abbotsfield School Uxbridge 894/6906 Abraham Darby Academy Telford 202/4285 Acland Burghley School London 931/8004 Activate Learning Oxford 307/4035 Acton High School London 919/4029 Adeyfield School Hemel Hempstead 825/6015 Akeley Wood Senior School Buckingham 935/4059 Alde Valley School Leiston 919/6003 Aldenham School Borehamwood 891/4117 Alderman White School and Language College Nottingham 307/6905 Alec Reed Academy Northolt 830/4001 Alfreton Grange Arts College Alfreton 823/6905 All Saints Academy Dunstable Dunstable 916/6905 All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham Cheltenham 340/4615 All Saints Catholic High School Knowsley 341/4421 Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Liverpool 358/4024 Altrincham College of Arts Altrincham 868/4506 Altwood CofE Secondary School Maidenhead 825/4095 Amersham School Amersham 380/6907 Appleton Academy Bradford 330/4804 Archbishop Ilsley Catholic School Birmingham 810/6905 Archbishop Sentamu Academy Hull 208/5403 Archbishop Tenison's School London 916/4032 Archway School Stroud 845/4003 ARK William Parker Academy Hastings 371/4021 Armthorpe Academy Doncaster 885/4008 Arrow Vale RSA Academy Redditch 937/5401 Ash Green School Coventry 371/4000 Ash Hill Academy Doncaster 891/4009 Ashfield Comprehensive School Nottingham 801/4030 Ashton -

5060113445643.Pdf

YEVGENY ZEMTSOV Instrumental and Chamber Music String Quartet (1962, rev. 2004) 19:19 1 I Lento – Allegro agitato – Lento doloroso – 9:07 2 II Allegro molto – 6:14 3 III Allegro agitato – Lento maestoso 3:58 4 Ballada for violin and piano (1959, rev. 2015) 5:46 Violin Sonata No. 1, in memoriam Sergei Prokofiev (1961, rev. 2001) 17:17 5 I Moderato 6:59 6 II Lento cantabile 4:35 7 III Allegro vivo 5:43 Three Inventions for piano (1965, rev. 2005) 6:25 8 No. 1 Fughetta (Allegro) 1:56 9 No. 2 Intermezzo (Adagio molto capriccioso) 3:11 10 No. 3 Toccatina (Presto) 1:18 11 Ohnemass for piano (2004) 3:43 Five Japanese Poems for soprano, two violins and cello (1987, rev. 2005) 8:47 Poetry by Matsuo Bashō (1644–94) and Ryota Oshima (1718–87); Russian translations by Vera Markova (1907–95) 12 No. 1 How silent is the garden (Bashō) 1:20 13 No. 2 On the naked branch of a tree sits a raven (Bashō) 1:40 14 No. 3 Shudder, o hill! (Bashō) 0:36 15 No. 4 O, this path through the undergrowth (Bashō) 3:00 16 No. 5 All is filled with silver moonlight (Oshima) 2:11 2 ASTOR PIAZZOLLA Cuatro Estaciones Porteñas (‘Four Seasons of Buenos Aires’; 1965–69) 16:08 arr. Yevgeny Zemtsov for string quartet (2003–16) 17 I Verano Porteño (‘Buenos Aires Summer’; 1965) 4:28 18 II Invierno Porteño (‘Buenos Aires Winter’; 1969) 2:48 19 III Primavera Porteña (‘Buenos Aires Spring’; 1970) 4:44 20 IV Otoño Porteño (‘Buenos Aires Autumn’; 1970) 4:08 21 Le grand Tango (1982) 11:32 arr. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No. -

A Study of Tyzen Hsiao's Piano Concerto, Op. 53

A Study of Tyzen Hsiao’s Piano Concerto, Op. 53: A Comparison with Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2 D.M.A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Lin-Min Chang, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2018 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Steven Glaser, Advisor Dr. Anna Gowboy Dr. Kia-Hui Tan Copyright by Lin-Min Chang 2018 2 ABSTRACT One of the most prominent Taiwanese composers, Tyzen Hsiao, is known as the “Sergei Rachmaninoff of Taiwan.” The primary purpose of this document is to compare and discuss his Piano Concerto Op. 53, from a performer’s perspective, with the Second Piano Concerto of Sergei Rachmaninoff. Hsiao’s preferences of musical materials such as harmony, texture, and rhythmic patterns are influenced by Romantic, Impressionist, and 20th century musicians incorporating these elements together with Taiwanese folk song into a unique musical style. This document consists of four chapters. The first chapter introduces Hsiao’s biography and his musical style; the second chapter focuses on analyzing Hsiao’s Piano Concerto Op. 53 in C minor from a performer’s perspective; the third chapter is a comparison of Hsiao and Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concertos regarding the similarities of orchestration and structure, rhythm and technique, phrasing and articulation, harmony and texture. The chapter also covers the differences in the function of the cadenza, and the interaction between solo piano and orchestra; and the final chapter provides some performance suggestions to the practical issues in regard to phrasing, voicing, technique, color, pedaling, and articulation of Hsiao’s Piano Concerto from the perspective of a pianist. -

Autumn 2015 DOWNLOAD

The International Music School founded by Yehudi Menuhin www.yehudimenuhinschool.co.uk — Registered Charity 312010 — Newsletter 62 — Autumn 2015 In particular, we acknowledge the generosity of The Oak Foundation, Sackler Trust, The Sir Siegmund Warburg Voluntary Anniversary Settlement, the Foyle Foundation, and Michael and Hilary Cowan for their transformational giving. We are thankful, too, to Appeal Update Friends of the School for leaving gifts in their wills. The School will be delighted to recognise this within our new facilities. Thanks to you, our Anniversary Appeal continues to go from Thanks to a small group of donors, the School is currently able strength to strength. Gifts and pledges from a wide range of to offer Matched Funding for every gift given between now and supporters have enabled the School to reach just over £2.5 June 2016, up to a value of £500,000. That means for every £1 million of the £3.5 million required to build and equip our new you donate, the School will double the value of your donation, Music Studios, leaving us only £920,000 to raise before the pound for pound. Naming opportunities for bursaries, rooms unveiling of the building in July 2016. We are also incredibly and equipment are still available. So, if you would like to join grateful to everyone who has contributed towards the bursaries us in our Appeal, please contact the Development Office on which help our students attend the School, irrespective of their [email protected] or telephone financial position. We would like to extend our sincere thanks 01932 584797. -

A Survey of Selected Piano Concerti for Elementary, Intermediate, and Early-Advanced Levels

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2017 A Survey of Selected Piano Concerti for Elementary, Intermediate, and Early-Advanced Levels Achareeya Fukiat Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Fukiat, Achareeya, "A Survey of Selected Piano Concerti for Elementary, Intermediate, and Early-Advanced Levels" (2017). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 5630. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/5630 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SURVEY OF SELECTED PIANO CONCERTI FOR ELEMENTARY, INTERMEDIATE, AND EARLY-ADVANCED LEVELS Achareeya Fukiat A Doctoral Research Project submitted to College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Piano Performance James Miltenberger, -

R Obert Schum Ann's Piano Concerto in AM Inor, Op. 54

Order Number 0S0T795 Robert Schumann’s Piano Concerto in A Minor, op. 54: A stemmatic analysis of the sources Kang, Mahn-Hee, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1992 U MI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 ROBERT SCHUMANN S PIANO CONCERTO IN A MINOR, OP. 54: A STEMMATIC ANALYSIS OF THE SOURCES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Mahn-Hee Kang, B.M., M.M., M.M. The Ohio State University 1992 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Lois Rosow Charles Atkinson - Adviser Burdette Green School of Music Copyright by Mahn-Hee Kang 1992 In Memory of Malcolm Frager (1935-1991) 11 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the late Malcolm Frager, who not only enthusiastically encouraged me In my research but also gave me access to source materials that were otherwise unavailable or hard to find. He gave me an original exemplar of Carl Relnecke's edition of the concerto, and provided me with photocopies of Schumann's autograph manuscript, the wind parts from the first printed edition, and Clara Schumann's "Instructive edition." Mr. Frager. who was the first to publish information on the textual content of the autograph manuscript, made It possible for me to use his discoveries as a foundation for further research. I am deeply grateful to him for giving me this opportunity. I express sincere appreciation to my adviser Dr. Lois Rosow for her patience, understanding, guidance, and insight throughout the research. -

A Menuhin Centenary Celebration

PLEASE A Menuhin Centenary NOTE Celebration FEATURING The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment of any kind during performances is strictly prohibited The Lord Menuhin Centenary Orchestra Philip Burrin - Conductor FEBRUARY Friday 19, 8:00 pm Earl Cameron Theatre, City Hall CORPORATE SPONSOR Programme Introduction and Allegro for Strings Op.47 Edward Elgar (1857 - 1934) Solo Quartet Jean Fletcher Violin 1 Suzanne Dunkerley Violin 2 Ross Cohen Viola Liz Tremblay Cello Absolute Zero Viola Quartet Sinfonia Tomaso Albinoni (1671 – 1751) “Story of Two Minstrels” Sancho Engaño (1922 – 1995) Menuetto Giacomo Puccini (1858 – 1924) Ross Cohen, Kate Eriksson, Jean Fletcher Karen Hayes, Jonathan Kightley, Kate Ross Two Elegiac Melodies Op.34 Edvard Grieg (1843 – 1907) The Wounded Heart The Last Spring St Paul’s Suite Op. 29 no.2 Gustav Holst (1874 – 1934) Jig Ostinato Intermezzo Finale (The Dargason) Solo Quartet Clare Applewhite Violin 1 Diane Wakefield Violin 2 Jonathan Kightley Viola Alison Johnstone Cello Intermission Concerto for Four Violins in B minor Op.3 No.10 Antonio Vivaldi (1678 – 1741) “L’estro armonico” Allegro Largo – Larghetto – Adagio Allegro Solo Violins Diane Wakefield Alison Black Cal Fell Sarah Bridgland Cello obbligato Alison Johnstone Concerto Grosso No. 1 Ernest Bloch (1880 – 1959) for Strings and Piano Obbligato Prelude Dirge Pastorale and Rustic Dances Fugue Piano Obbligato Andrea Hodson Yehudi Menuhin, Lord Menuhin of Stoke d’Abernon, (April 22, 1916 - March 12, 1999) One of the leading violin virtuosos of the 20th century, Menuhin grew up in San Francisco, where he studied violin from age four. He studied in Paris under the violinist and composer Georges Enesco, who deeply influenced his playing style and who remained a lifelong friend. -

An Analysis of His Piano Concerto in E-Flat Major

SERGEI TANEYEV (1856-1915): AN ANALYSIS OF HIS PIANO CONCERTO IN E-FLAT MAJOR AND ITS RELATIONSHIP TO TCHAIKOVSKY’S PIANO CONCERTO NO. 1 Louise Jiayin Liu, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Joseph Banowetz, Major Professor Jeffrey Snider, Committee Member Adam Wodnicki, Committee Member Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Liu, Louise Jiayin, Sergei Taneyev (1856-1915): An Analysis of His Piano Concerto in E- flat Major and Its Relationship to Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No.1. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2007, 38 pp., 25 examples, bibliography, 26 titles. This lecture recital seeks to prove that Sergei Taneyev’s only piano concerto is a valuable addition to the piano concerto repertoire for historical and theoretical examination. Taneyev’s biographical background proves he was one of the major figures in Russian musical life during the late nineteenth century. For one who had such an important role in music history, it is an unfortunate that his music has not been popular. Through letters to contemporary composers and friends, Taneyev’s master teacher Tchaikovsky revealed why his music and piano concerto were not as popular as they should have been. This lecture recital examines Taneyev’s compositional style and illustrates his influence in the works of his famous student Sergei Rachmaninoff through examples from Taneyev’s Piano Concerto in E-flat Major and Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. -

The Development of the Russian Piano Concerto in the Nineteenth Century Jeremy Paul Norris Doctor of Philosophy Department of Mu

The Development of the Russian Piano Concerto in the Nineteenth Century Jeremy Paul Norris Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music 1988 December The Development of the Russian Piano Concerto in the Nineteenth Century Jeremy Paul Norris The Russian piano concerto could not have had more inauspicious beginnings. Unlike the symphonic poem (and, indirectly, the symphony) - genres for which Glinka, the so-called 'Father of Russian Music', provided an invaluable model: 'Well? It's all in "Kamarinskaya", just as the whole oak is in the acorn' to quote Tchaikovsky - the Russian piano concerto had no such indigenous prototype. All that existed to inspire would-be concerto composers were a handful of inferior pot- pourris and variations for piano and orchestra and a negligible concerto by Villoing dating from the 1830s. Rubinstein's five con- certos certainly offered something more substantial, as Tchaikovsky acknowledged in his First Concerto, but by this time the century was approaching its final quarter. This absence of a prototype is reflected in all aspects of Russian concerto composition. Most Russian concertos lean perceptibly on the stylistic features of Western European composers and several can be justly accused of plagiarism. Furthermore, Russian composers faced formidable problems concerning the structural organization of their concertos, a factor which contributed to the inability of several, including Balakirev and Taneyev, to complete their works. Even Tchaikovsky encountered difficulties which he was not always able to overcome. The most successful Russian piano concertos of the nineteenth century, Tchaikovsky's No.1 in B flat minor, Rimsky-Korsakov's Concerto in C sharp minor and Balakirev's Concerto in E flat, returned ii to indigenous sources of inspiration: Russian folk song and Russian orthodox chant. -

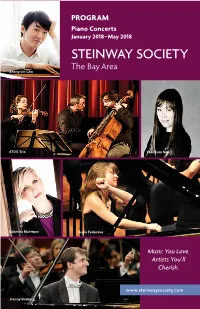

Steinway Society 17-18 Program

PROGRAM Piano Concerts January 2018–May 2018 Steinway Society The Bay Area Seong-Jin Cho ATOS Trio Yeol Eum Son Gabriela Martinez Anna Fedorova Music You Love. Artists You’ll Cherish. www.steinwaysociety.com Kenny Broberg Steinway Society - The Bay Area Letter from the President Depends Upon Your Support Dear Patron, Steinway Society – The Bay Area is led by volunteers who love piano and In his book, What Makes It Great: Short Masterpieces, classical music, and we are always looking for like-minded people. Here Great Composers, conductor Rob Kapilow asks what are a few ways you can help bring international concert pianists, in- makes a piece of classical music great. His answer: school educational experiences, master classes, and student performance memorable melody, rich harmonies, addictive opportunities to our community. rhythm, influence on other composers, and the work’s role in one’s life. Buy a Season or Series-4 Subscription Your subscription provides extended support while giving you the gift of Steinway Society is honored to present great music, works created beautiful music. over the centuries, performed by international artists who grace these works with sublime interpretation and dramatic virtuosity. Become a Donor Ticket sales cover only about 60% of our costs. Your gifts are crucial for Our season’s second half features six artists judged “best” by everything we do, and are greatly appreciated. Please consider a legacy prestigious international competitions, by key critics and by gift such as a recital series in your name that will help continue bringing enthusiastic audiences. In January 2018, Cliburn Silver Medalist magnificent classical music to future generations.