The Singing Subject

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myrtle's Only

! ! " Myrtle’s Only Son" Dale Rayburn" ! ! ! Title: The Cowboy and the Songcatcher" ! Overview" Students are introduced to history of American Folk Music through a study of folklorists in the field. Known as “songcatchers,” early folk music collectors John and Alan Lomax are !responsible for collecting and preserving thousands of folk songs, including Home on the Range. ! Students will listen to examples of traditional and contemporary folk music, choose a folk song, !study it in depth and write a personal essay about the song. ! After watching an interview with Alan Lomax, students will conduct a folklife field project of their own, using the Library of Congress resource Folklife and Fieldwork: A Layman’s Introduction !to Field Techniques.! ! ! Subjects" American History, Folklore, Musicology, Language Arts! ! Age Group" Secondary (Grades 6 - 12)! ! Standards" 21st Century Learning Skills:" • !Critical Thinking and Reasoning! • !Information Literacy! • !Collaboration! • !Invention! • !Self-Direction! !• Skills for Living in the World! Colorado Academic Standards:" Social Studies" • Regions have different issues and perspectives! • Use geography to research, gather data and ask questions! • Become familiar with the idea that people are interconnected by geography! History" • Develops moral understanding, defines identity and creates an appreciation of how things change while building skills in judgment and decision-making. ! • Enhances the ability to read varied sources and develop the skills to analyze, interpret and communicate. ! • The -

Traditional Song

3 TraditionalSong l3-9 Traditional Song Week realizes a dream of a comprehensive program completely devoted to traditional styles of singing. Unlike programs where singing takes a back seat to the instrumentalists, it is the entire focus of this week, which aims to help restore the power of songs within the larger traditional music scene. Here, finally, is a place where you can develop and grow in confidence about your singing, and have lots of fun with other folks devoted to their own song journeys. Come gather with us to explore various traditional song genres under the guidance of experienced, top-notch instructors. When singers gather together, magical moments are bound to happen! For Traditional Song Week’s ninth year and our celebration of The Swannanoa Gathering’s 25th Anniversary, we are proud to present a gathering of highly influential singers and musicians who have remained devoted over the years to preserving and promoting traditional song. Tuesday evening will be our big Hoedown for a Traditional Country, Honk-Tonk, Western Swing Song and Dance Night. Imagine singing to a house band of Josh Goforth, Robin and Linda Williams and Ranger Doug or Tim May, Tim O’Brien, and Mark Weems! So, bring your boots and hats, your voices and instruments, and get ready to bring on the fun! Our Community Gathering Time each day just after lunch affords us the opportunity to experience together, as one group, diverse topics concerning our shared love of traditional song. This year’s spotlight will feature folks who have been “on the road” and singing for quite a while. -

School Nixes Leasing Agreement with Township

25C The Lowell Volume IS, Issue 2 Serving Lowell Area Readers Since 1893 Wednesday, November 21, 1990 earns The Lowell Ledger's "First Buck Contest" turnout was a.m., bagged the buck at 7:45 a.m. better than voter turnout on election day. On Saturday, Vezino bagged a four-point buck with a Well, not quite, but 10 area hunters did walk through the bow. Ledger d(X)r between 7:30 a.m. and 12:30 p.m. on Wednes- Don Post. Ada. was along the Grand River on the flats, day. when he used one shot from his 16-gauge to drop a seven- The point sizes varied from four to eight-point. The weight point. 160-165 pound buck at 8 a.m. Post, hunting since of the bucks fluctuated from 145-200 pounds and the spreads the age of 14. said the seven is the biggest point size buck on the rack were anywhere from eight to 15 inches. he has ever shot. Lowell's Jack Bartholomew was the first hunter to hag Chuck Pfishner, Lowell, fired his winning shot at 7:50 and drag his buck to the Ledger office at 7:35 a.m. Barth- a.m. east on Four Mile. Using a 12-gauge, Pfishner shot olomew was out of the house by 6 a.m., saw his first buck an eight-point, 145-150 pound buck with a nine-inch spread. at 6:55 and shot it at 7:10. Randy Mclntyre. Lowell, was in Delton when he dropped "When I first saw the buck it was about 100 yards away. -

The Ballads of the Southern Mountains and the Escape from Old Europe

B AR B ARA C HING Happily Ever After in the Marketplace: The Ballads of the Southern Mountains and the Escape from Old Europe Between 1882 and 1898, Harvard English Professor Francis J. Child published The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, a five volume col- lection of ballad lyrics that he believed to pre-date the printing press. While ballad collections had been published before, the scope and pur- ported antiquity of Child’s project captured the public imagination; within a decade, folklorists and amateur folk song collectors excitedly reported finding versions of the ballads in the Appalachians. Many enthused about the ‘purity’ of their discoveries – due to the supposed isolation of the British immigrants from the corrupting influences of modernization. When Englishman Cecil Sharp visited the mountains in search of English ballads, he described the people he encountered as “just English peasant folk [who] do not seem to me to have taken on any distinctive American traits” (cited in Whisnant 116). Even during the mid-century folk revival, Kentuckian Jean Thomas, founder of the American Folk Song Festival, wrote in the liner notes to a 1960 Folk- ways album featuring highlights from the festival that at the close of the Elizabethan era, English, Scotch, and Scotch Irish wearied of the tyranny of their kings and spurred by undaunted courage and love of inde- pendence they braved the perils of uncharted seas to seek freedom in a new world. Some tarried in the colonies but the braver, bolder, more venturesome of spirit pressed deep into the Appalachians bringing with them – hope in their hearts, song on their lips – the song their Anglo-Saxon forbears had gathered from the wander- ing minstrels of Shakespeare’s time. -

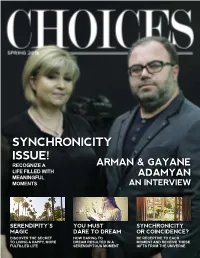

Synchronicity Issue! Recognize a Arman & Gayane Life Filled with Adamyan Meaningful Moments an Interview

SYNCHRONICITY ISSUE! RECOGNIZE A ARMAN & GAYANE LIFE FILLED WITH ADAMYAN MEANINGFUL MOMENTS AN INTERVIEW SERENDIPITY’S YOU MUST SYNCHRONICITY MAGIC DARE TO DREAM OR COINCIDENCE? DISCOVER THE SECRET HOW DARING TO BE RECEPTIVE TO EACH TO LIVING A HAPPY, MORE DREAM RESULTED IN A MOMENT AND RECEIVE THESE FULFILLED LIFE SERENDIPITOUS MOMENT GIFTS FROM THE UNIVERSE CONTENTS FROM THE SYNCHRONICITY INTERVIEW EDITOR 10 THE SECRET TO 33 ARMAN & GAYANE SERENDIPITY’S MAGIC ADAMYAN had moved on to the city on which my During my cancer experience, I prayed BY JOY HUNTSMAN BY JUDI MOREO mother had placed the pin. Is that the for a sign that I was choosing the right same as “synchronicity”? treatment as I was foregoing chemo HOW DOES and radiation. Then in a restroom, 13 Or, how about these examples: there was a sign on the wall that said, SYNCHRONICITY WORK? BY JOAN S. PECK LIFESTYLE “The Power that made the body heals You end a horrible relationship and the body. It is the only way.” LOBBYING FOR A CHANGE 04 JOURNALING IS A CHOICE ften in life, things hap- right away you meet a person who 29 BY WILNONA & JADE BY JUDI MOREO pen that seem “syn- seems to better suit you. It all seems so “synchronistic.” But, chronistic” or “coin- is it a coincidence or is our conscious- UNANSWERED PRAYERS STAY PRODUCTIVE WHILE O cidental.” Are there You go to the store and you tell the ness evolving? Have we attracted cer- 40 BY GINA GELDBACH-HALL 16 really such happen- passenger in your car that you always tain people into our lives because we AWAY ON BUSINESS ings? In this issue, our writers have get a parking place up front and at have lessons to learn? Or, have we BY AMBER DE LA GARZA ARE YOU LICENSED TO chosen to explore the subject from that very moment, a car pulls out of gotten to a place in our consciousness 42 many different angles. -

Lana Del Rey - Born to Die: the Paradise Edition Pdf

FREE LANA DEL REY - BORN TO DIE: THE PARADISE EDITION PDF Lana Del Rey | 136 pages | 01 Mar 2013 | Hal Leonard Publishing Corporation | 9781458448620 | English | United States Born to Die - Paradise Edition - Rolling Stone Paradise is the third extended play and second major release by American singer and songwriter Lana Del Rey ; it was released on November 9, by Universal Music. It was additionally packaged with the reissue of her second studio albumBorn to Dietitled Born to Die: The Paradise Edition. The EP's sound has been described as baroque pop [1] and trip hop. Upon its release, Paradise received generally favorable reviews from music critics. The extended play debuted at No. It also debuted at No. That same month, an EP of the same name was made available for digital purchase, containing the film along with the three aforementioned songs. In an interview with RTVE on June 15,Del Rey announced that she had Lana del Rey - Born to Die: The Paradise Edition working on a new album due in November, and that five tracks had already been written, [3] two of them being " Young and Beautiful " [ citation needed ] and "Gods and Monsters", [ citation needed ] and another track titled "Body Electric", which was performed and announced as one of her songs at BBC Radio 1's Hackney Weekend. The prior album's re-release, titled Born to Die: The Paradise Editionwas available for pre-order offering an immediate download of "Burning Desire" in some countries. The song served as the soundtrack for a short film called Desire[8] directed by Ridley Scott and starring Damian Lewis. -

Semester 2 – 2014

The SEMESTER 2 2014 Marrma’ Rom Two Worlds Foundation Congratulations to Dion and Jerol Wunungmurra Semester Two 2014 was highlighted by the fantastic achievement of two of our students graduating from Year 12. Dion and Jerol have been part of the Foundation since 2012 and we are very proud of them and what they have accomplished during the last 3 years. We are also very proud of them for deciding to return to Geelong next year and continue their endeavors to become Aboriginal Health Workers. [ Below is a short article by Jerol about the St. Joseph’s College Graduation Mass, for which Dions and Jerols’ parents flew down to attend: On the 19th of October 2014, the second week of school in Term 4, Dion’s parents and my dad came down to Geelong. They drove to Gove from Gapuwiyak and stayed in town. The next day they went to Gove airport and they flew from Gove to Cairns and 2 hours later they flew to Melbourne. Dion and I woke up early morning and Cam drove us to Gull bus. We checked in then the bus driver drove us to Tullamarine. We only waited for about 5 minutes then we saw them arrive. We caught the Skybus to Southern Cross and waited for the others in the city. We were performing at the Melbourne Festival that day. After the festival finished we caught a train back to Geelong. Dad was staying with me and Dion and his mum and dad were staying at Narana Cultural Centre. On Monday we went to St. -

After Four Successful Editions

fter four successful editions the A concepts which inspired the creation of Ten Days on the Island in 2001 have well and truly proved themselves. With performances and works across the artistic spectrum drawn from island cultures around the world, including of course our own, Ten Days on the Island has become Tasmania’s premier cultural event and an event of national and international significance. Under the creative leadership of our Artistic Director, Elizabeth Walsh, I MY ISLAND HOME know that the 2009 event will take us to even greater heights. I would like to thank the Tasmanian Government, our corporate sponsors and Philos patrons, local government and the governments of countries around the world for their continuing support for Ten Days on the Island. They are making a very significant contribution to building and enriching our island culture. SIR GUY GREEN Chairman, Ten Days on the Island 1 he opening bash for 2009 will T centre on Constitution Dock. In addition to Junk Theory, there are free bands, the sounds of Groove Ganesh (see page 24), food stalls, roving entertainment and the first of the amazing Dance Halls will be held just up Macquarie Street in City Hall (see opposite). The CELEBRATE Tasmanian Museum & Art Gallery will be open late so you can see all the shows (see pages 4 & 34) with special performances by the Ruined piano man, Ross Bolleter in the café courtyard… Don’t miss it for quids! HOBART CONSTITUTION DOCK DAVEY STREET 27 MARCH FROM 7.30PM Supported by JUNK TASMANIA t dusk on opening night, in the heart of Hobart at Constitution Dock, a HOBART LAUNCESTON A traditional Chinese junk, the Suzy Wong, will drift by, her sails set and CONSTITUTION DOCK SEAPORT DAVEY STREET 4 & 5 APRIL FROM DUSK filled with moving imagery. -

ROGÉRIO FERRARAZ O Cinema Limítrofe De David Lynch Programa

ROGÉRIO FERRARAZ O cinema limítrofe de David Lynch Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Comunicação e Semiótica Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo (PUC/SP) São Paulo 2003 PONTIFÍCIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DE SÃO PAULO – PUC/SP Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Comunicação e Semiótica O cinema limítrofe de David Lynch ROGÉRIO FERRARAZ Tese apresentada à Banca Examinadora da Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, como exigência parcial para obtenção do título de Doutor em Comunicação e Semiótica – Intersemiose na Literatura e nas Artes, sob a orientação da Profa. Dra. Lúcia Nagib São Paulo 2003 Banca Examinadora Dedicatória Às minhas avós Maria (em memória) e Adibe. Agradecimentos - À minha orientadora Profª Drª Lúcia Nagib, pelos ensinamentos, paciência e amizade; - Aos professores, funcionários e colegas do COS (PUC), especialmente aos amigos do Centro de Estudos de Cinema (CEC); - À CAPES, pelas bolsas de doutorado e doutorado sanduíche; - À University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), por me receber como pesquisador visitante, especialmente ao Prof. Dr. Randal Johnson, supervisor de meus trabalhos no exterior, e aos professores, funcionários e colegas do Department of Spanish and Portuguese, do Department of Film, Television and Digital Media e do UCLA Film and Television Archives; - A David Lynch, pela entrevista concedida e pela simpatia com que me recebeu em sua casa; - Ao American Film Institute (AFI), pela atenção dos funcionários e por disponibilizar os arquivos sobre Lynch; - Aos meus amigos de ontem, hoje e sempre, em especial ao Marcus Bastos e à Maite Conde, pelas incontáveis discussões sobre cinema e sobre a obra de Lynch; - E, claro, a toda minha família, principalmente aos meus pais, Claudio e Laila, pelo amor, carinho, união e suporte – em todos os sentidos. -

The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection a Handlist

The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection A Handlist A wide-ranging collection of c. 4000 individual popular songs, dating from the 1920s to the 1970s and including songs from films and musicals. Originally the personal collection of the singer Rita Williams, with later additions, it includes songs in various European languages and some in Afrikaans. Rita Williams sang with the Billy Cotton Club, among other groups, and made numerous recordings in the 1940s and 1950s. The songs are arranged alphabetically by title. The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection is a closed access collection. Please ask at the enquiry desk if you would like to use it. Please note that all items are reference only and in most cases it is necessary to obtain permission from the relevant copyright holder before they can be photocopied. Box Title Artist/ Singer/ Popularized by... Lyricist Composer/ Artist Language Publisher Date No. of copies Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Dans met my Various Afrikaans Carstens- De Waal 1954-57 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Careless Love Hart Van Steen Afrikaans Dee Jay 1963 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Ruiter In Die Nag Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1963 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Van Geluk Tot Verdriet Gideon Alberts/ Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1970 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Wye, Wye Vlaktes Martin Vorster/ Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1970 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs My Skemer Rapsodie Duffy -

My Island Home – Christine Anu (Original Lyrics by Neil Murray and Warumpi Band)

Lesson 1 Learning Intention: To listen to and appreciate music/song • Success Criteria: - my enjoyment of the song - my feelings towards the song In this lesson you are going to listen to and watch the music video My Island Home. https://safeYouTube.net/w/pWgr The song My Island Home was written and composed by Neil Murray (1986) for Warumpi Band singer George Burarrwanga. The song references the singer’s home on Elcho Island off the coast of Arnhem Land. My Island Home was then covered by Christine Anu in 1995 and performed at the closing ceremony of the 2000 Olympics in Sydney. R supervisor. Record your responses on an audio recording and return it to your teacher. • Do you like or dislike the song? • What do you like or dislike about the song? • How does the song make you feel? My Island Home Student and Supervisor 21 Booklet Miss Koeferl Reflect on My Island Home - Christine Anu It’s your turn to be a music critic! Think about: • the lyrics • the instruments • the tempo (pace) • any other musical features you noticed. What I liked What I disliked How it made me feel What did you think of the music video? Where would you film My Island Home? Draw your own visuals below: 2 Lesson 2 Learning Intention: To identify the structural parts of a song • I can recognise the verse Success Criteria: • I can recognise the chorus In this lesson, you will be exploring the structure of a song, mainly the verse and a chorus. A song is a musical composition that is made up of music and lyrics (the words) that are sung by a singer. -

Car/Bus Accident Shows Need for Public Awareness No Injuries Incurred When Car Fails to Stop for School Bus Unloading Students

25«! HC«S « S0K3- 3,,K 3IHDER,* SffilWOPORr. MICHIC* 49284 Volume 17. Issue 25 Lowell Area Readers Since 1893 Wednesday, May 5,1993 Car/bus accident shows need for public awareness No injuries incurred when car fails to stop for school bus unloading students Wet roads and a misun- Galvin was carrying two pas- alize that the red flashing lights derstanding of the law may sengers, Laura Radle, 1800 mean all motorists must stop," have been the cause of an ac- W. Main, and Darlene Hess, said Larry Mikulski Bus Su- cident Thursday on M-21 just of Lowell. No one in either perintendent for Lowell. "It west of Settle wood. The acci- car was seriously injured. looks to me like the second dent involved two cars and a Christenson was coming car was expecting the first car school bus. to a stop bccause the buses' to keep on going." A car driven by Robert red lights were flashing and it Mikulski went on to ex- Galvin, 18(K)W. Main, struck was unloading children. The plain, "until the public is more another car driven by Robert other car apparently could not educated, either by law en- Christenson, 2535 Gee Dr., as stop in time to avoid hitting forcement officials or some he was coming to a stop for a his car. other organization, this kind school busunloadingchildren. "Some police officers tell of accident will happen more The school bus was just me that these types of acci- frequently. Only next time grazed and no children were dents are occurring more fre- some child may get hurt." in spite of the damage to Robert Galvin's 1984 Olds, no serious iiyuries occurred injured.