The Effects of a Major Disaster on the Musical Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SISS Cycle Champs Time Trial

South Island Schools Championships Southburn, Canterbury 07 Jul 2018 Individual Time Trial Results 4km Individual TT PlaceRace No Name Team Time Under 13 Girls 19 Lilly Greenwood Rangi Ruru Girls School 9:04.24 210 Caitlin Kelly Verdon College 9:07.87 311 Emily Toomey Bluestone School 9:11.79 44 Milly Gallagher Rangi Ruru Girls School 9:12.73 57 Grace Griffin Southland Girls High School 9:20.74 63 Kirsty Watts Fernside School 9:26.61 7 6 Mya Wolfenden Rangi Ruru Girls School 9:36.18 81 Susan Petrie Cobham Intermediate 9:49.10 95 Kate Russell James Hargest College 9:52.28 102 Zoe Spillane Craighead Diocesan School 9:58.30 118 Jorja Gibbons Tahuna Normal Intermediate 10:59.41 Under 13 Boys 128 Noah Hollamby Bluestone School 8:17.92 217 Kayne Borrie James Hargest College 8:28.96 320 Elliott Perrett Hillview Christian School 8:39.06 426 Frankie Thomson Verdon College 8:40.08 5 13 Oliver Borrie James Hargest College 8:49.59 623 Magnus Jamieson Southland Boys High School 8:55.06 714 Robbie Cochrane Medbury School 8:58.28 816 Carter Guichard Holy Family School 9:05.43 918 Ben Ashman Medbury School 9:13.15 1021 Jack McLeod James Hargest College 9:31.82 1124 Will Kitching Barton Rural 9:47.61 1212 Matthew Davidson Cobham Intermediate 9:50.81 1322 Jimmy Davison Medbury School 9:51.10 1425 Ben Crawford Medbury School 9:54.23 1519 Cerban Sprague Gleniti School 9:54.57 1615 Luca Sanders Cobham Intermediate 9:58.61 1727 Hamish Barlow Southland Boys High School 10:02.15 Under 14 Girls 130 Caitlin Murphy Marlborough Girls College 8:50.82 229 Brooke Keown -

Read Our Thank You List

The Housing, Heating and Health Study would not have been possible without the help of many people and organisations and we would like to take the opportunity here to thank: Our community partners: Tu Kotahi Maori Asthma Trust, Waiwhetu Marae and Community Planners in the Hutt Valley, Porirua Health Plus and Te Ropu Awhina in Porirua. Pacific Trust Canterbury, Community and Public Health and Te Amorangi Richmond in Christchurch, The Otago Asthma Society in Dunedin and Te Runaka O Awarua in Bluff. Our insulation retrofitters and heater suppliers and installers: Energy Smart, Community Energy Action and Kati Huirapa Runaka ki Puketeraki who supplied and installed each house with insulation, Air Con (using Fujitsu and Mitsubishi products) who installed the heat pumps, Solid Energy who installed the Wood Pellet Burners and Hutt Gas and Plumbing who installed the Flued Gas Heaters. Thank you also to Smart Power who managed the tender and installation process. The energy companies, that supplied household energy data Contact Energy, Genesis Energy, Meridian Energy, Empower and Trustpower. General practitioners, who supplied data on patient visits Avalon Medical Centre, Acheson Avenue Community Health Centre, Aurora Health Centre, Barrington Medical Centre, Belfast Medical Centre, Bluff Medical Centre, Broadway Medical Centre Dunedin Ltd, Capital Care Health Centre, Cashmere Medical Practice, Caversham Medical Centre, Christchurch Family Clinic, Christchurch South Health Centre, Community Support Medical Centre, Corpore Sano Ltd. Surgery, Doctors on Riccarton, Dr A.E.J.Fitchett, Dr Andrew Campbell Smillie, Dr Asha Lata Sai, Dr Astrid Windfuhr, Dr D. Ritchie Consulting Rooms, Dr G.V.A. de Croos, Dr H.T. -

Core Loop Place Name School ID

Wednesday, 10 March 2021 Core Loop Place Name School ID Time Lap 1 Lap 2 Lap 3 Lap 4 Start 1 Jacob TURNER Rangiora High School 261 0:26:39 0:06:47 0:06:31 0:06:37 0:06:41 Race 5, Wave 1 2 Fergus O'NEILL Cashmere High School 128 0:27:52 0:07:19 0:06:50 0:06:50 0:06:52 Race 5, Wave 1 3 Eli SUGRUE Riccarton High School 278 0:28:23 0:07:29 0:06:53 0:07:11 0:06:49 Race 5, Wave 2 4 Bailey GRAHAM St Andrew's College 329 0:28:44 0:07:29 0:07:11 0:07:12 0:06:50 Race 5, Wave 1 5 Henry MCMECKING Cashmere High School 133 0:28:51 0:07:45 0:06:58 0:06:57 0:07:09 Race 5, Wave 2 6 Austin MYLES Christchurch Boys’ High School 174 0:29:19 0:07:48 0:07:10 0:07:06 0:07:13 Race 5, Wave 1 7 Jack DUNNETT Christchurch Boys’ High School 192 0:29:42 0:07:42 0:07:15 0:07:24 0:07:19 Race 5, Wave 1 8 George ROOKES Christ's College 154 0:30:01 0:07:55 0:07:11 0:07:21 0:07:33 Race 5, Wave 1 9 Eli LEONARD Shirley Boys’ High School 315 0:30:21 0:07:46 0:07:22 0:07:28 0:07:44 Race 5, Wave 1 10 Dylan WEBB Shirley Boys’ High School 314 0:30:34 0:07:57 0:07:35 0:07:41 0:07:19 Race 5, Wave 1 11 William GRIFFITHS Christchurch Boys’ High School 220 0:31:06 0:07:48 0:07:40 0:07:39 0:07:58 Race 5, Wave 1 12 John LAURIE Cashmere High School 135 0:31:53 0:08:07 0:07:54 0:07:55 0:07:55 Race 5, Wave 2 13 Joseph CONNOLLY St Andrew's College 337 0:32:12 0:08:05 0:07:43 0:08:09 0:08:15 Race 5, Wave 1 14 Maria LAURIE Cashmere High School 138 0:32:13 0:08:16 0:07:54 0:08:01 0:08:00 Race 5, Wave 2 15 Amelie MACKAY Cashmere High School 124 0:33:26 0:08:13 0:08:08 0:08:28 0:08:34 Race 5, Wave -

Oia-1156529-SMS-Systems.Pdf

School Number School Name SMSInfo 3700 Abbotsford School MUSAC edge 1680 Aberdeen School eTAP 2330 Aberfeldy School Assembly SMS 847 Academy for Gifted Education eTAP 3271 Addington Te Kura Taumatua Assembly SMS 1195 Adventure School MUSAC edge 1000 Ahipara School eTAP 1200 Ahuroa School eTAP 82 Aidanfield Christian School KAMAR 1201 Aka Aka School MUSAC edge 350 Akaroa Area School KAMAR 6948 Albany Junior High School KAMAR ACT 1202 Albany School eTAP 563 Albany Senior High School KAMAR 3273 Albury School MUSAC edge 3701 Alexandra School LINC-ED 2801 Alfredton School MUSAC edge 6929 Alfriston College KAMAR 1203 Alfriston School eTAP 1681 Allandale School eTAP 3274 Allenton School Assembly SMS 3275 Allenvale Special School and Res Centre eTAP 544 Al-Madinah School MUSAC edge 3276 Amberley School MUSAC edge 614 Amesbury School eTAP 1682 Amisfield School MUSAC edge 308 Amuri Area School INFORMATIONMUSAC edge 1204 Anchorage Park School eTAP 3703 Andersons Bay School Assembly SMS 683 Ao Tawhiti Unlimited Discovery KAMAR 2332 Aokautere School eTAP 3442 Aoraki Mount Cook School MUSAC edge 1683 Aorangi School (Rotorua) MUSAC edge 96 Aorere College KAMAR 253 Aotea College KAMAR 1684 Apanui School eTAP 409 AparimaOFFICIAL College KAMAR 2333 Apiti School MUSAC edge 3180 Appleby School eTAP 482 Aquinas College KAMAR 1206 THEArahoe School MUSAC edge 2334 Arahunga School eTAP 2802 Arakura School eTAP 1001 Aranga School eTAP 2336 Aranui School (Wanganui) eTAP 1002 Arapohue School eTAP 1207 Ararimu School MUSAC edge 1686 Arataki School MUSAC edge 3704 -

Physical Disability Specialist Service Provider in Waimakariri District

Physical Disability Specialist Service Provider in Waimakariri District, Christchurch City, Banks Peninsula and Selwyn District Isleworth School Ph: 03 359 8553 59A Farrington Ave Fax: 03 359 8560 Bishopdale Christchurch List of schools covered by the specialist service provider (Isleworth School): Waimakariri District Ashgrove School Pegasus Bay School Ashley School Rangiora Borough School Clarkville School Rangiora High School Cust School Rangiora New Life School Fernside School St Joseph's School (Rangiora) Kaiapoi Borough School St Patrick's School (Kaiapoi) Kaiapoi High School Sefton School Kaiapoi North School Southbrook School Karanga Mai Young Parents College Swannanoa School Loburn School Tuahiwi School North Loburn School View Hill School Ohoka School West Eyreton School Oxford Area School Woodend School Christchurch City Aranui High School Our Lady of Fatima School (Chch) Avonside Girls' High School Our Lady of Assumption School (Chch) Addington School Our Lady of Victories School Aranui School (Christchurch) Ouruhia Model School Avondale School (Christchurch) Papanui High School Avonhead School Papanui School Bamford School Paparoa Street School Banks Avenue School Parkview School Beckenham School Queenspark School Belfast School Rangi Ruru Girls' School Bishopdale School Rawhiti School Breens Intermediate School Redcliffs School Bromley School Redwood School (Christchurch) Burnside High School Riccarton High School Burnside Primary School Riccarton School Canterbury Christian College Rudolf Steiner School (Christchurch) Casebrook -

An Annotated Bibliography of Published Sources on Christchurch

Local history resources An annotated bibliography of published sources on the history of Christchurch, Lyttelton, and Banks Peninsula. Map of Banks Peninsula showing principal surviving European and Maori place-names, 1927 From: Place-names of Banks Peninsula : a topographical history / by Johannes C. Andersen. Wellington [N.Z.] CCLMaps 536127 Introduction Local History Resources: an annotated bibliography of published sources on the history of Christchurch, Lyttelton and Banks Peninsula is based on material held in the Aotearoa New Zealand Centre (ANZC), Christchurch City Libraries. The classification numbers provided are those used in ANZC and may differ from those used elsewhere in the network. Unless otherwise stated, all the material listed is held in ANZC, but the pathfinder does include material held elsewhere in the network, including local history information files held in some community libraries. The material in the Aotearoa New Zealand Centre is for reference only. Additional copies of many of these works are available for borrowing through the network of libraries that comprise Christchurch City Libraries. Check the catalogue for the classification number used at your local library. Historical newspapers are held only in ANZC. To simplify the use of this pathfinder only author and title details and the publication date of the works have been given. Further bibliographic information can be obtained from the Library's catalogues. This document is accessible through the Christchurch City Libraries’ web site at https://my.christchurchcitylibraries.com/local-history-resources-bibliography/ -

PSC Swim Results 2015

Wharenui Pool - Site License HY-TEK's MEET MANAGER 5.0 - 3:06 PM 30/03/2015 Page 1 2015 Canterbury Primary School Sports - 30/03/2015 2015 primary schools Results Event 1 Mixed 9 Year Olds 200 SC Meter Freestyle Relay Team Relay Seed Time Finals Time Points 1 Medbury Prep. School A NT 2:35.47 1) Mason, Emma W9 2) Smith, Bonnie W9 3) Clements, Jacob M9 4) Allison, Cam M9 2 Methven Primary School A NT 2:49.33 1) Allred, Caitlin W9 2) Currie, Patrick M9 3) Lill, Hunter M9 4) Wareing, Hannah W9 3 Sumner A NT 2:49.72 1) Crump, Meg W9 2) Hately, Gracie W9 3) Rae, Tom M9 4) Ovendale, Nate M9 4 Paparoa St A NT 2:56.90 1) Timbs, William M9 2) DE Cuevas, Robbie M9 3) Anderson, Jessie W9 4) Kneebone, Molly W9 5 Tai Tapu School A NT 2:59.81 1) Wrathall, Hugo M9 2) Dixon, Charlie M9 3) Martin, Maggie W9 4) McConchie, Kate W9 6 Waitakiri School A NT 3:00.47 1) Hooper, Corbin M9 2) Crighton, Lane M9 3) McLelland, Sophie W9 4) Van Den Linden, Sophie W9 7 Cashmere Primary School A NT 3:02.94 1) Gimblett, Jed M9 2) Allott, Finn M9 3) McClelland, Mei-Lin W9 4) Block, Gemma W9 8 Dunsandel School A NT 3:03.62 1) Barns, Lucy W9 2) Tanner, Emma W9 3) Lough, Jack M9 4) Colenso, Alex M9 9 Roydvale School A NT 3:05.80 1) Montgomery, Lola W9 2) Day, Samantha W9 3) McCullough, Conor M9 4) Eastes, Riley M9 10 Rawhiti School Qeii A NT 3:10.31 1) Muir, Jessica W9 2) Coleman, Joey M9 3) Carson, Freya W9 4) Coetzee, Josh M9 11 Cust Area School A NT 3:11.78 1) Benson, Tinesha W9 2) McLachlan, Quade M9 3) Riley, George M9 4) Thompson, Libby W9 12 St Martins School A NT -

In Memoriam 2013

In Memoriam 2013 Christ’s College Old Boys’ Association Table of Contents 4331 OWEN CHRISTOPHER JOHNSTONE 5 4373 JOHN ROBERT ALLISON 5 4510 JOHN ELDERSON MILLAR 6 4587 DUNCAN LEO JOHNS 7 4733 ROBIN HUNTER YOUNG 8 4738 SHOLTO HAMILTON GEORGESON 8 4823 ALAN JAMES BRUCE 10 4842 JOHN HUMPHREY COOKE 11 4887 CHARLES FREDERICK COLLINGWOOD OLDHAM 12 5058 MALCOLM SLEEMAN ROBERTSON 14 5132 BRUCE SHAW McLAUGHLIN 15 5168 BERNARD ALEXANDER WITTE 16 5305 DUNCAN ROSS FRASER 17 5370 THOMAS SAMUEL WILSON 17 5451 KEVIN RUSSELL UREN 18 5557 STEPHEN JOHN STUDHOLME BARKER 19 5649 HENRY RICHARD CARVER 20 5881 TIM IVON HERVEY PHIPPS 20 6034 PAUL MOORE HARGREAVES 20 6235 JULIAN JOHN WATTS 22 6436 PAUL GURNEY NORRIS 23 7125 PETER McARTHUR ACLAND 24 7272 MICHAEL JOHN CAMBRIDGE 25 7574 GEORGE THOMAS CARLTON KAIN 25 7763 ANDREW GERALD TURNBULL 26 7821 CHARLES FRANK FARTHING 27 8402 ANDREW NEVITT REESE 31 9425 MICHAEL DAVID JENNINGS BUSH 32 9575 BRENT ANDREW FARRAR 32 10754 GUY WILLIAM NELSON 33 13840 DAVID JONATHAN CHUBB CLAY 34 OWEN CHRISTOPHER JOHNSTONE 4331 Aged 94 Owen was born at Springbank Farm, South Canterbury, on 5 March 1919. He attended Waihi School and Christ’s College followed by some years study at St Wilfred’s in England and Lincoln College, the latter interrupted by the outbreak of World War II. After serving in the Fleet Air Arm during the war, Owen returned to take over Springbank Farm, married Prue Wanklyn in 1948 and devoted his life to his family, his farm and his community. He was a practical farmer and one who showed great empathy with the land and what it was capable of producing, being justifiably proud of his Aberdeen Angus cattle and the various breeds of sheep he introduced as farming and climatic conditions changed. -

Team Points.Pdf

2018 SI Schools Championships Southburn/Levels Raceway, Timaru 7-8 July 2018 Team Points Competition - Hayden Godfrey Challenge Cup (Individual Events: 5,3,2,1 Team Events: 3,2,1 Countbacks on Wins, 2nd's, etc) Place Team Area Points 1 James Hargest College Invercargill 39 2 Christchurch Boys High School Christchurch 39 3 Rangi Ruru Girls School Christchurch 23 4 Christchurch Girls High School Christchurch 15 5 Southland Boys High School Invercargill 14 6 Verdon College Invercargill 13 7 Bluestone School Timaru 12 8 Southland Girls High School Invercargill 11 9 Roncalli College Timaru 10 10 St Margaret's College Christchurch 10 11 Marlborough Girls College Blenheim 10 12 Villa Maria College Christchurch 10 =13 Ladbrooks School Christchurch 8 =13 Mt Aspiring College Wanaka 8 15 Rangiora High School Rangiora 8 16 Burnside High School Christchurch 7 17 Papanui High School Christchurch 6 18 Mountainview High School Timaru 6 =19 Ashburton College Ashburton 5 =19 Cashmere High School Christchurch 5 =19 Nelson College Nelson 5 22 Rolleston College Rolleston 5 23 Christ's College Christchurch 5 24 Wakatipu High School Queenstown 4 25 Hillview Christian School Christchurch 4 26 Lincoln High School Lincoln 3 =27 Darfield High School Darfield 2 =27 Fernside School Rangiora 2 =27 Timaru Boys High School Timaru 2 30 Otago Boys High School Dunedin 1 Balmacewen Intermediate Dunedin 0 Barton Rural Fairview 0 Cathedral Grammar School Christchurch 0 Central Southland College Winton 0 Cobham Intermediate Christchurch 0 Craighead Diocesan School Timaru 0 -

Organisationname

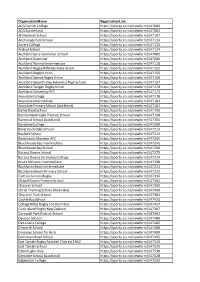

OrganisationName RegistrationLink ACG Parnell College https://sporty.co.nz/viewform/147080 ACG Sunderland https://sporty.co.nz/viewform/147081 Al-Madinah School https://sporty.co.nz/viewform/147107 Anchorage Park School https://sporty.co.nz/viewform/147116 Aorere College https://sporty.co.nz/viewform/147123 Arahoe School https://sporty.co.nz/viewform/147134 Auckland Girls' Grammar School https://sporty.co.nz/viewform/147085 Auckland Grammar https://sporty.co.nz/viewform/147086 Auckland Normal Intermediate https://sporty.co.nz/viewform/147118 Auckland Rugby Referees Association https://sporty.co.nz/viewform/147152 Auckland Rugby Union https://sporty.co.nz/viewform/147156 Auckland Samoa Rugby Union https://sporty.co.nz/viewform/147169 Auckland Seventh-Day Adventist High School https://sporty.co.nz/viewform/147157 Auckland Tongan Rugby Union https://sporty.co.nz/viewform/147170 Auckland University RFC https://sporty.co.nz/viewform/147171 Avondale College https://sporty.co.nz/viewform/147178 Avondale Intermediate https://sporty.co.nz/viewform/147181 Avondale Primary School (Auckland) https://sporty.co.nz/viewform/147182 Bailey Road School https://sporty.co.nz/viewform/147196 Bairds Mainfreight Primary School https://sporty.co.nz/viewform/147198 Balmoral School (Auckland) https://sporty.co.nz/viewform/147204 Baradene College https://sporty.co.nz/viewform/147209 Baverstock Oaks School https://sporty.co.nz/viewform/147213 Bayfield School https://sporty.co.nz/viewform/147214 Beachlands Maraetai AFC https://sporty.co.nz/viewform/147265 Blockhouse -

PHN School Allocation List 2019

PHN School Allocation List 2019 Contact Phone: 03-383-6877 Fax: 03-383-6878 Email: [email protected] Name of school Name of Lead PHN Addington School Rowan MacLeod Aidanfield Christian School Ruth Fitzgerald Akaroa Area School Wendy Aspray Allenton School Ange Harris Allenvale Special School And Res Centre Barbara-Ann Harper Amberley School Catherine Dowle Amuri Area School Catherine Dowle Ao Tawhiti Unlimited Discovery Katie Mullord Arahina School Fiona Kennedy Araria Springs Primary Wendy Aspray Ashburton Borough School Ange Harris Ashburton Christian School Ange Harris Ashburton College Ange Harris Ashburton Intermediate Ange Harris Ashburton Netherby School Ange Harris Ashgrove School Anne Braid Ashley School Anne Braid Avonhead School Tracy Stewart Avonside Girls' High School Fiona Kennedy Bamford School Frances Ryan Banks Avenue School Fiona Kennedy Beckenham School Anna Marshall Belfast School Kim Hill Bishopdale School Kirstin Lambie Breens Intermediate School Barbara-Ann Harper Broadfield School School Wendy Aspray Bromley School Frances Ryan Broomfield School Catherine Dowle Burnham School Belinda Ritchie Burnside High School Barbara-Ann Harper Burnside Primary School Barbara-Ann Harper Carew - Peel Forest School Pam Eaden Casebroook Intermediate School Kirstin Lambie Cashmere High School Anna Marshall Cashmere Primary School Rowan MacLeod Catholic Cathedral College Katie Mullord Chertsey School Pam Eaden Cheviot Area School Catherine Dowle Chisnallwood Intermediate School Fiona Kennedy Cholmondeley School Rowan MacLeod -

2021 SI Schools Championships RR Start Lists

Mike Pero Motorsport Park, Christchurch 11 July 2021 Road Race START LISTS RACE 1 UNDER 13 BOYS 3 LAPS 10.5KM 10:00AM Race No Name School 1 Louis Audeau Cathedral Grammar School 2 Jake Bennett Medbury Prep. School 3 Benson Boys Limehills School 4 Zach Brookland Opihi College 5 Arthur Brown Medbury Prep. School 6 Matthew Burton-Lyall Medbury Prep. School 7 Riley Crampton Medbury Prep. School 8 Cooper Gough James Hargest College 9 Daniel Grieve John McGlashan College 10 George Hegan Medbury Prep. School 11 Louis Hiatt Medbury Prep. School 12 Gwilym Jones Hillview Christian School 13 Sharr Louis Medbury Prep. School 14 Noah Madgwick Medbury Prep. School 15 Nisal Pathirana Medbury Prep. School 16 Finn Taylor Cathedral Grammar School 17 Flynn Turnbull Gleniti School 18 Marshall Watson Holy Family School 19 Otis Wheeler Medbury Prep. School 171 Samuel Cook Hillview Christian School RACE 2 UNDER 13 GIRLS 3 LAPS 10.5KM 10:02AM Race No Name School 20 Sophie Best Gleniti School 21 Vesper Woodfield Cobham Intermediate 172 Violetta Dacre Selwyn House School RACE 3 UNDER 14 BOYS 3 LAPS 10.5KM 10:20AM Race No Name School 22 Patrick Aitken Medbury Prep. School 23 Reid Allison Hillview Christian School 24 James Aroyo Christchurch Boys High School 25 Oliver Clark Christchurch Boys High School 26 Brady Connelly Kavanagh College 27 William Crawford St Andrew's College 28 Josh Davies Christchurch Boys High School 29 Louis Fogarty Medbury Prep. School 30 Andre Free Cobham Intermediate 31 Dardy Harrington Cathedral Grammar School 32 Jesse Johnston Timaru Boys' High School 33 Silas Jones Hillview Christian School 34 Armani McLennan Bluestone School 35 Conor Toomey Bluestone School 36 Caleb Turner Gleniti School 37 Cohnor Walsh Medbury Prep.