VIVEKANANDA INTERNATIONAL FOUNDATION About

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Female Athlete and Spectacle in Bollywood: Reading Mary Kom and Dangal

ISSN 2249-4529 www.pintersociety.com GENERAL SECTION VOL: 9, No.: 2, AUTUMN 2019 REFREED, INDEXED, BLIND PEER REVIEWED About Us: http://pintersociety.com/about/ Editorial Board: http://pintersociety.com/editorial-board/ Submission Guidelines: http://pintersociety.com/submission-guidelines/ Call for Papers: http://pintersociety.com/call-for-papers/ All Open Access articles published by LLILJ are available online, with free access, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial License as listed on http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ Individual users are allowed non-commercial re-use, sharing and reproduction of the content in any medium, with proper citation of the original publication in LLILJ. For commercial re- use or republication permission, please contact [email protected] 68 | The Female Athlete and Spectacle in Bollywood… The Female Athlete and Spectacle in Bollywood: Reading Mary Kom and Dangal Shweta Sharma Abstract: This paper engages with the representation of the female athlete in Indian cinema. Specific references will be made to the cinematic portrayal of female boxers and wrestlers in Bollywood to argue that female boxers and wrestlers are portrayed as ‘masculine’. However, the sportswoman’s assertion of her femininity in a space exclusively occupied by men leads to ‘gender trouble’. To enunciate this argument two biopics, Mary Kom (2014) and Dangal (2016), will be analyzed. It would be observed that when a female boxer/wrestler tries to reinforce her identity, she is either subjected to criticism or faces failure. However, the argument that sportswomen are termed as ‘masculine’ does not necessarily imply that female athletes aren’t objects of the male gaze. -

NT All Pages 2019.Indd

WEDNESDAY SPPORTSORTS 6 20 MARCH 2019 CHENNAI Tahir spins it Proteas’ way Helps South Africa beat Sri Lanka in thrilling Super Over Ritu Phogat Cape Town, Mar 20 (PTI): wicketkeeper, despite Quinton de Kock featuring in the playing eleven. Miller did Needing only 15 runs to dropped from TOPS Imran Tahir, emerged as the hero for justice to the role as he held a catch off South Africa as he successfully defended Dale Steyn’s bowling off the second ball defend, South African New Delhi, Mar 20 (PTI): 15 runs in the super over to help South of the match, dismissing Niroshan Dick- Africa beat Sri Lanka in a nail-biting fi rst wella and made a stumping. Miller then skipper, Faf du Plessis IImranmran TTahirahir Wrestler Ritu Phogat, youngest of T20 internation of the three-match series hit 41 off 23 balls but South Africa’s lower the celebrated ‘Phogat Sisters’, was at New Lands, Cape Town, Tuesday. order collapsed as the home side lost eight on Tuesday dropped from the gov- After restricting Sri Lanka to 134 for wickets in the end pushing the match into gave the ball to Imran Tahir ernment’s Target Olympic Podium seven in 20 overs, South Africa choked the super over. Scheme (TOPS) after she decided to badly as the contest came to an end with ‘We didn’t handle it well with the bat in and the move paid rich shift her loyalty to Mixed Martial the scores level. Batting fi rst in the super the last fi ve or six overs but getting another Arts (MMA). -

1. Who Is the Prime Minister of India? A. Sharad Pawar B

1. Who is the Prime minister of India? a. Sharad Pawar b. Narendra Modi c. Lalu Prasad Yadav d. Rahul Gandhi Correct answer – b 2. Dr. Patangrao Kadam, who passed away, was associated with which political party? a. Indian National Congress b. Bharatiya Janata Party c. Nationalist Congress Party d. Communist Party of India (Marxist) Correct answer – a 3. Which cricket team has won the 45th edition of the Deodhar Trophy 2018? a. Karnataka b. Gujarat c. India B d. Tamil Nadu Correct answer – c 4. The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) has tied up with which PSU company to develop low-cost lithium ion batteries for electric vehicles? a. Antrix Corporation b. Bharat Heavy Electricals Ltd (BHEL) c. Bharat Dynamics d. Bharat Electronics Ltd Correct answer – b 5. __________________ is the Miss World 2018 a. Manushi Chhillar b. Sushmita Sen c. Aishwarya Rai d. Lara Dutta Correct answer – a 6. Which Bollywood actress will be honoured with the Dadasaheb Phalke Award as Internationally Acclaimed Actress? a. Priyanka Chopra b. Aishwarya Rai Bachchan c. Deepika Padukone d. Sonam Kapoor Correct answer – a 7. Which union minister has recently launched a Swachh Survekshan (Gramin) -2017? a. Rajnath Singh b b. Narendra Modi c. M Venkaiah Naidu d. Narendra Singh Tomar Correct answer – d 8. Which city is hosting the first International exhibition and Conference on AYUSH and Wellness sector “AROGYA 2017”? a. Pune b. Jaipur c. New Delhi d. Lucknow Correct answer – c 9. Who will lead India in ICC Under-19 Cricket World Cup 2018? a. Riyan Parag b. Himanshu Rana c. -

Miss World Winners List in Hindi

Copyright By www.taiyarihelp.com Miss World Winners List in Hindi हम आप सभी प्रतियोगी छात्रⴂ को बिा दे की जो वि饍यार्थी ककसी भी एक ददिसीय परीक्षा की िैयारी Miss World कर रहे है !! उनको यह जानना बहुि ही ज셁री होिा है 啍यⴂकी अ啍सर परीक्षा मᴂ Winners List से प्र�न पूछे जािे है| आज हम (1951 से लेकर 2018) िक के सारे Miss World Winners के नाम हℂ को लेकर आए है जजसे आप सभी तनचे वििार से पढ़ सकिे है !!! अगर आपको यह नो絍स अ楍छे लगे िो हमᴂ कमᴂट करके ज셁र बिाए. List of Miss World Winners List :- • 1951 – कीकी हा कामसन (Kiki Håkansson) – वीडन (Sweden) • 1952 – लु ुई फ्लॉडडन (Louise Flodin) – वीडन (Sweden) • 1953 – डडनायस पेररया (Denise Perrier) – फ्ा車स ( France) • 1954 – एटिगान कोिाडा (Antigone Costanda) – ममस्र (Egypt) • 1955 – सुजाना दु ुव्जम (Susana Duijm) – वेनजे ुएला (Venezuela) • 1956 – पे絍िा सरमान (Petra Schürmann) – जममनी (Germany) • 1957 – मेररिा मल車डस (Marita Lindahl) – फिनलℂड (Finland) • 1958 – पेनेलोप ऐनी काुेुेलेन (Penelope Anne Coelen) – दक्षिण अफ्ीका (South Africa) • 1959 – कोराइन राि हैयर (Corine Rottschäfer) – नीदरलℂ蕍स (Netherlands) • 1960 – नोमाम कपा嵍ले (Norma Cappagli) – अजᴂिीना ( Argentina ) • 1961 – रोजी मेरी िᴂकले (Rosemarie Frankland) – इ車गलℂड (England) • 1962 – कैथरीन ला蕍मस (Catharina Lodders) – नीदरलℂ蕍स (Netherlands) • 1963 – कैुैरोल जोन कािोडम (Carole Joan Crawford) – जमैका (Jamaica) • 1964 – एनी ए मसडनी (Ann Sydney) – इ車गलℂड (England) • 1965 – लेली लℂ嵍ले (Lesley Langley) – इ車गलℂड (England) • 1966 – रीता िाररया (Reita Faria) – भारत (India) Design By www.taiyarihelp.com & www.taiyarihelp.com Copyright By www.taiyarihelp.com -

Current Affairs=04/05-06-2020 HRD & Urban Development Ministries

Current Affairs=04/05-06-2020 HRD & Urban development ministries & AICTE jointly launches 1st of its kind student internship programme, “TULIP” On June 4, 2020, Shri Ramesh Pokhriyal `Nishank’, Minister, Human Resource Development, Shri Hardeep S. Puri, MoS (I/C), Housing & Urban Affairs, and All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE) have jointly launched a 1st of its kind online portal for `The Urban Learning Internship Program (TULIP)’ – A program for providing internship opportunities to fresh graduates in all Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) and Smart Cities across the country. This scheme was announced by Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman in the budget 2020-21 under the theme ‘Aspirational India’. College students having a level of B. Tech, B planning, B. Arch, BA, BSc, BCom, LLB can register for internships as per their interest Citizen skill mapping under Vande Bharat Mission called “SWADES” launched by Govt. The joint initiative by the Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship(MSDE), Ministry of Civil Aviation (MoCA) and Ministry of External Affairs(MEA). SWADES is launched in order to conduct a skill mapping exercise of the returning citizens under the Vande Bharat Mission (VBM). The SWADES Skill Card will help the citizens with job prospects and bridge the demand-supply gap.This initiative will help in deployment of the returning Indian workforce with matching skill set. About Vande Bharat Mission: The government initiated to bring back stranded Indian nationals home during coronavirus-induced lockdown from other -

Daily Updated Current Affairs – 17.11.2017 to 19.11.2017

DAILY UPDATED CURRENT AFFAIRS – 17.11.2017 TO 19.11.2017 NATIONAL Cabinet approves Continuation of sub-schemes under Umbrella Scheme “Integrated Child Development Services (a) The sub-schemes that will be continued are Anganwadi Services, Scheme for Adolescent Girls, Child Protection Services and National Crèche Scheme. (b) Besides, cabinet has also approved conversion of National Crèche Scheme from Central Sector to Centrally Sponsored Scheme. This scheme aims to provide a safe place for mothers to leave their children while they are at work. (c) These sub-schemes will be continued till November 30, 2018 with financial outlay of over Rs.41000 crore. (d) Above mentioned sub-schemes are continuing from the 12th Five Year Plan. However, Government has rationalised these sub-schemes in financial year 2016-17 and have been brought under Umbrella ICDS as its sub-schemes. (e) It is expected that around 11 crore children, pregnant women & Lactating Mothers and the Adolescent Girls will gain benefits through these schemes. Cabinet okays increase in carpet area of houses under PMAY (a) Cabinet has approved increase in carpet area of houses eligible for interest subsidy under the Credit Linked Subsidy Scheme (CLSS) for the Middle Income Group (MIG) under Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY). (b) For MIG I, the existing carpet area of 90 sq mt (968.752 sq ft) will be increased to 120 sq mt ( 1291.668 sq ft.) and instead of 110 sq mt (1184.03 sq ft) for MIG II category, it will now be 150 sq mt ( 1614.585 sq ft). These changes will be effective Jan 1, 2017, the date when it was initially implemented. -

Motherhood, Women Issues and Masculinity: Deconstructing Global Beauty Pageants

International Journal of Research on Social and Natural Sciences Vol. III Issue 1 June 2018 ISSN (Online) 2455-5916 Journal Homepage: www.katwacollegejournal.com Motherhood, Women Issues and Masculinity: Deconstructing Global Beauty Pageants Yeamanur Khatun, English, Panchmura College, India Article Record: Received Mar. 30 2018, Revised paper received May 22 2018, Final Acceptance June 6 2018 Available Online June 7 2018 Abstract This paper aims at deconstructing the fashion beauty pageants' organisational claim to provide the contestant models and winners platforms to treading through global relations and achieve worldwide recognition, while actually fostering the myth of beauty with culturally-fabricated norms of femininity and masculinity holding up the concepts of 'Complete' or 'Perfect' woman or man to the fore. Here, we seek to talk about the political hegemony working from behind the colossal fashion world economy and how the pageants are being manipulated by the larger capitalist countries through their market capturing tactics. But what we intend most is to show that the pageant contestants sometimes act as passive resistants, countering the hegemonic discourse to dismantle the norms set by the Fashion Politics, starting from Manushi Chhillar's vote for remunerative motherhood to Reita Faria's choice of forming her own identities in their attempt to refuse the laid out set of ideologies. Keywords: Deconstruction, Fashion, Beauty pageants, motherhood, femininity, masculinity, Norms, Binaries 1. Introduction Much ink has been split upon the normative binarization of femininity and masculinity as culturally- fabricated constructions and their presentation in international beauty pageants is termed ideological and discursive. Beauty pageants treat gender as one more category along with other categories of 'caste', or 'nation' as reflected in the seemingly 'worthy' title ascription such as "Miss India" or in the very entrance forms they fill in ticking on the given boxes of gender, nationality ,religion or maritalstatus. -

Diana Hayden, the 1997 Miss World Miss World Was Born in Was Born In

DIANA HAYDEN Model, Miss World, Actress Diana Hayden, the 1997 Miss World was born in 1973 in Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh. She was the only Miss World to have won a hat-trick at the pageant - Miss Photogenic, Miss Beachwear and Miss World 1997. A tomboy as a teenager, Diana grew up to be a ravishing beauty. Diana's parents split up at her very young age, but her family including her mother and brother were still very close- knit. After completing her schooling at St Ann's High School, Secunderabad, she graduated from Osmania University in English through correspondence. Diana shifted to Mumbai to pursue her career goals. She then moved to Bangalore working for the event management company Encore and then again to Bombay. Diana had a brief stint in modelling and did a couple of fashion shows in Bangalore and Mumbai. Then she started work in the public relations division of BMG Crescendo, the music company where she helped handle the careers of artistes like Anaida and Mehnaz. ItIt was Anaida who forced her to send her pictures for the Miss India Contest and the rest is history. R.K. NARAYAN Writer One of the most famous Indian writers in English Language, R.K Narayan was born in 1906 in Madras. He was educated in Mysore and settled there for over half a century. Narayan created the enchanting fictional world of Malgudi through his several novels and short stories which captivated his readers throughout the world and more recently millions of Indian Television viewers, who saw TV adaptations of many Malgudi stories. -

November 19Th News: International: UN-Led Ministerial Conference In

November 19th news: International: UN-led ministerial conference in Moscow agrees universal commitment to end tuberculosis On 17th November, 75 ministers announced a landmark agreement to take urgent action to end tuberculosis (TB) by 2030 at the conclusion of a World Health Organization (WHO) conference in Moscow, Russia, on eradicating the world's deadliest infectious disease. Together with UN Deputy Secretary-General Amina Mohammed and Mr. Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Russian President Vladimir Putin opened the Conference on 16 November. The gathering brought together delegates from 114 countries. The newly-minted Moscow Declaration to End TB is a promise to increase multisectoral action as well as track progress, and build accountability. It will also inform the first UN General Assembly High-Level Meeting on TB in 2018, which will seek further commitments from heads of State. Since 2000, global efforts to combat the disease have saved an estimated 53 million lives and reduced the TB mortality rate by 37 per cent. However, progress in many countries has stalled, global targets are off-track and persistent gaps remain in TB care and prevention. As a result, TB still kills more people than any other infectious disease. There are also major problems associated with antimicrobial resistance, and it is the leading killer of people with HIV. More than 1,000 participants took part in the two-day conference, which was attended by ministers and country delegations, as well as representatives of civil society and international organizations, scientists and researchers. The end result was a collective commitment to ramp up action on four fronts. The first pledge was to rapidly move to achieve universal health coverage by strengthening health systems and improving access to people-centred TB prevention and care so no one is left behind. -

DU BA Honours Multimedia and Mass Communication

DU BA Honours Multimedia and Mass Communication Questi Question Sr.No Question Body Options on Id Description 1 12151 DU_J19_BA_ India’s first film museum is in 18601:Mumbai, MMC_Q01 18602: Delhi, 18603:Jaipur, 18604:Kolkata, 2 12152 DU_J19_BA_ “A People’s Constitution” is written by 18605:Bhim Rao Ambedkar, MMC_Q02 18606: Narendra Damodaran Modi, 18607:Siddharth Dev, 18608:Rohit De, 3 12153 DU_J19_BA_ The “Geet Govind” is composed by 18609:Sri Krishna, MMC_Q03 18610: Jaidev, 18611:Valmiki, 18612:Ved Vyas, 4 12154 DU_J19_BA_ Match the islands renamed in Andaman by PM Modi 18613:Neil Island – Swaraj Dweep , MMC_Q04 18614:Ross Island – Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose Dweep , 18615:Havelock Island – Shaheed Dweep , 18616:None of the above , 5 12155 DU_J19_BA_ The odd one out is 18617:Laila Majnu , MMC_Q05 18618:Heer Ranjha , 18619:Mirza Sahibaan , 18620:Rustom Sohrab , 6 12156 DU_J19_BA_ The Cellular Jail is located in 18621:Maldives , MMC_Q06 18622:Laskhwadeep , 18623:Sri Lanka , 18624:Andaman and Nicobar , 7 12157 DU_J19_BA_ The farthest object in space has been named 18625:Neptune , MMC_Q07 18626:Pluto , 7 12157 DU_J19_BA_ The farthest object in space has been named MMC_Q07 18627:Milky Way , 18628:Ultima Thule , 8 12158 DU_J19_BA_ The Yellow Vest movement refers to 18629:A hygiene programme in MMC_Q08 India , 18630:A soap advertisement in Korea , 18631:Popular uprising in France , 18632:Popular uprising in USA , 9 12159 DU_J19_BA_ The first woman Defence Minister of India is 18633:Nirmala Sitharaman, MMC_Q09 18634: Sushma Swaraj, 18635:Vijaylaxmi -

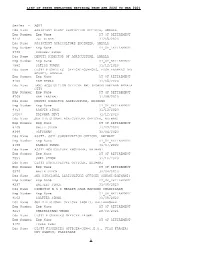

List of State Govt Employees Retiring Within One Year

LIST OF STATE EMPLOYEES RETIRING FROM APR 2020 TO MAR 2021 Series - AGRI Ddo Name ASSISTANT PLANT PROTECTION OFFICER, AMBALA Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 9312 JAI SINGH 31/05/2020 Ddo Name ASSISTANT AGRICULTURE ENGINEER, AMBALA Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 6738 SUKHDEV SINGH Ddo Name DEPUTY DIRECTOR OF AGRICULTURE, AMBALA Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 7982 SATISH KUMAR 31/12/2020 Ddo Name DISTT FISHERIES OFFICER-CUM-CEO, FISH FARMERS DEV AGENCY, AMBALA Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 8166 RAM NIWAS 31/05/2020 Ddo Name LAND ACQUISITION OFFICER PWD (POWER)HARYANA AMBALA CITY Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 8769 RAM PARSHAD 31/08/2020 Ddo Name DEPUTY DIRECTOR AGRICULTURE, BHIWANI Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 9753 RANVIR SINGH 31/12/2020 10203 KRISHNA DEVI 31/12/2020 Ddo Name SUB DIVISIONAL AGRICULTURE OFFICER, BHIWANI Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 8105 DALIP SINGH 31/07/2020 8399 SATYAWAN 30/04/2020 Ddo Name ASSTT. SOIL CONSERVATION OFFICER, BHIWANI Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 6799 RAMESH KUMAR 31/07/2020 Ddo Name ASSTT AGRICULTURE ENGINEER, BHIWANI Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 7593 SHER SINGH 31/10/2020 Ddo Name DISTT HORTICULTURE OFFICER, BHIWANI Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 6576 WAZIR SINGH 30/04/2020 Ddo Name SUB DIVSIONAL AGRICULTURE OFFICER SIWANI(BHIWANI) Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 8237 BALJEET SINGH 31/05/2020 Ddo Name DIRECTOR E S I HEALTH CARE HARYANA CHANDIGARH Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 8562 CHATTER SINGH 30/09/2020 Ddo Name SUB DIVISIONAL -

M.Des Program-GAT

Directions (Questions 1-5): Fill in the blank. 1. The farmers ________ their farms, if they had known that a thunderstorm was approaching. (1) will leave (2) would leave (3) will have left (4) would have left 2. The fireman managed to put ________ the fire. (1) away (2) down (3) out (4) off 3. There ________ any message from my teacher since she moved to London. (1) is not (2) was not (3) has not been (4) had not been 4. I asked him if I ________ borrow his car for a day. (1) will (2) could (3) can (4) should 5. ________ following all the instructions closely, he missed out an important guideline. (1) Instead of (2) Although (3) In spite of (4) Otherwise Directions (Questions 6-10) : Each of these questions consists of a sentence which is divided into four parts, numbered (1) to (4). Only one part in each sentence is not acceptable in standard written English. Identify that part which contains an error. 6. (1) The engineer reminded (2) them to have a (3) thoroughly cleaning of the (4) machine after each use. 7. (1) This Project which is funded (2) by the United Nations (3) has helps over four lakh Indians (4) overcome poverty. 8. (1) It was apparent for everyone present (2) that if the patient did not receive (3) medical attention fast (4) he would die. 9. (1) The accelerating pace of life (2) in our metropolitan city (3) has had the tremendous effect (4) on the culture and life-style of the people.