Executive Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

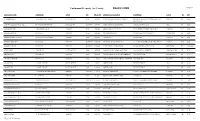

Unclaimed Property for County: EDGECOMBE 7/16/2019

Unclaimed Property for County: EDGECOMBE 7/16/2019 OWNER NAME ADDRESS CITY ZIP PROP ID ORIGINAL HOLDER ADDRESS CITY ST ZIP A1 CREDIT TAX S 107 SE MAIN ST SUITE 408 ROCKY MOUNT 27801 16019636 CONTINENTAL CASUALTY COMPANY TREASURY ANALYSIS CONTROL 23S 333 S CHICAGO IL 60604 WABASH AVE AARON P KELLY & JOYCE A KE 4877 SHEPHERDS WAY DR BATTLEBORO 27809-8930 15476041 ERIE INSURANCE EXCHANGE 100 ERIE INSURANCE PL ERIE PA 16530 AARON RENTALS 1104 WESTERN BLVD TARBORO 27886 15052212 EDGECOMBE COUNTY CSC 301 ST ANDREW STREE PO DRAWER 9 TARBORO NC 27886 ABRAMS ARTHUR PO BOX 175 PINETOPS 27864 14830205 PPG INDUSTRIES INC ONE PPG PLACE ATT TAX DEPT PITTSBURGH PA 15272 ABRAMS BARBECUE REST 609 WEST WILSON STREET TARBORO 27886 15774709 US FOODS INC PO BOX 29291 PHOENIX AZ 85038 ABRAMS GERALD W PO BOX 351 PINETOPS 27864-0351 15321804 WINDSTREAM HOLDINGS, INC. C/O COMPUTERSHARE 250 ROYALL STREET CANTON MA 02021 ABRAMS JO BETH PO BOX 351 PINETOPS 27864-0351 14909422 UNITI GROUP INCORPORATED 90 PARK AVENUE - 25TH FLOOR NEW YORK NY 10016-0000 ACREY ERIC L 13231 NC 43 N ROCKY MOUNT 27801 15075155 PEAK PROPERTY & CASUALTY CORP 1800 NORTH POINTE DRIVE STEVENS POINT WI 54481 ADAMS GEOFF 407 S 5TH ST PINETOPS 27864 15825219 LOWES COMPANIES INC & SUBSIDIARIES 1000 LOWES BLVD MOORESVILLE NC 28117 ADAMS HEATHER D PO BOX 1465 TARBORO 27886 14950966 LOCAL GOVERNMENT FEDERAL CREDIT UNION1000 WADE AVE RALEIGH NC 27605 ADAMS TOYA 216 ASHLAND AVE ROCKY MOUNT 27801 15480646 AMWAY CORP 7575 E FULTON ST ADA MI 49355 ADAMS TOYA 216 ASHLAND AVE ROCKY MOUNT 27801 15480261 AMWAY -

Newsletter Exclusively Presented by Issue 15 | May / June 2013 Launching Travel Retail Petit Robustos

newsletter ExClusIVEly PrEsEntEd by IssuE 15 | May / junE 2013 LAUNCHING TRAVEL RETAIL PETIT ROBUSTOS Gallery Name: Petit robustos leNGth: 102 mm riNG: 50 PreseNtatioN: • special cedar box of 10 units – 2 rows of 5 units Petit robustos of each brand • limited production of 5.000 for the whole world the tenth anniversary of seleccion robustos and seleccion Piramides, brands. this edition comes under the label of travel retail, and, like which have become symbolic for its segment, was marked by a new its predecessors, will bring pleasure to the connoisseurs of the gift product – seleccion Petit robustos. the novelty here is the two-sided segment with its rare cigars in the Petit robustos format, which are not position of the cigars, which are now 10 – two for each of the global produced on a large scale – Cohiba, Montecristo and H. upmann. COHIBA PIRAMIDE EXTRA NEW TUBOS Medium to strong in intensity of taste, Cohiba Piramides Extra has all Gallery Name: Piramides extra the characteristics of an exclusive edition: new format Piramides Extra, leNGth: 160 mm a three-stage fermentation process, and limited production. riNG: 54 Visually the vitola introduces a number of innovations, connected with on it, a fine figural tube with a special relief logo of the brand and limited the cigar world: a new relief ring with a holographic imprint embossed quantities, presented in boxes of three tubes each. PARTAGAS SERIE D N5 Gallery Name: Petit robustos leNGth: 110 mm riNG: 50 When El 2008 Partagas serie d n5 was first launched at the market, many serie d n5 is definitely your choice if you are going out for a coffee were quick to envisage that this cigar would go beyond the boundaries with friends, or you have about 30 minutes to indulge in your passion of the limited series, and would continue to bring pleasure to its lovers. -

JORF N° 0134 Du 11 Juin 2021

JORF N° 0134 du 11 juin 2021 DESIGNATION DES PRODUITS PRIX DE VENTE EN FRANCE CONTINENTALE Anciens prix de vente Nouveaux prix de vente aux aux consommateurs consommateurs NOUVEAU Au REFERENCE ACTUELLE AVEC LIBELLE Au LIBELLE A A l'unité conditionneme A l'unité DEJA HOMOLOGUE conditionnement HOMOLOGUER nt FOURNISSEUR : LOGISTA France n°01 FABRICANT : BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO Autres tabacs à fumer Neo Sticks Tabac à chauffer classique Violet 4,6 Sans changement (5,6g), en 20 unités Neo Sticks Tabac à chauffer Polaire sélection 5,3 Sans changement (5,6g), en 20 unités Neo Sticks Tabac à chauffer Iceberg sélection 5,3 Sans changement (5,6g), en 20 unités Neo Sticks Tabac à chauffer Alaska sélection 5,3 Sans changement (5,6g), en 20 unités Neo Sticks Tabac à chauffer classique Doré 4,6 Sans changement (5,6g), en 20 unités Neo Sticks Tabac à chauffer Doré (5,6g), en 20 4 Sans changement unités Neo Sticks Tabac à chauffer classique Jaune 4,6 Sans changement (5,6g), en 20 unités Neo Sticks Tabac à chauffer Jaune (5,6g), en 20 4 Sans changement unités Neo Sticks Tabac à chauffer Alaska (5,6g), en 20 4 Sans changement unités Neo Sticks Tabac à chauffer Iceberg (5,6g), en 20 4 Sans changement unités Neo Sticks Tabac à chauffer classique Alaska 4,6 Sans changement (5,6g), en 20 unités Neo Sticks Tabac à chauffer classique Iceberg 4,6 Sans changement (5,6g), en 20 unités Neo Sticks Tabac à chauffer Double (5,6g), en 20 4 Sans changement unités Neo Sticks Tabac à chauffer classique Polaire 4,6 Sans changement (5,6g), en 20 unités Neo Sticks Tabac à -

Catalog Cigar 2

Cohiba, Fidel Castros preferred brand, was created in 1966 as Havanas premier brand for diplomatic purposes. Since 1982, it was offered to the public in three sizes: Lanceros, Coronas Especiales and Panetelas. In 1989, three more sizes were added to complete the classic line namely: Esplendidos, Robustos and Exquisitos. In 1992, the following five sizes were further made in order to commemorate the 500th anniversary of the discovery of Cuba in 1492: Siglo I, II, III, IV and V. Name Lenght Ring Box Price BEHIKE 54 10 144 mm 54 10 28.958.000 VNĐ ESPLENDIDOS 25 178 mm 47 25 41.699.000 VNĐ EXQUISITOS 25 125 mm 33 25 14.157.000 VNĐ MEDIO SIGLO 25 102 mm 52 25 21.030.000 VNĐ PIRAMIDES EXTRA 10 160 mm 54 10 15.316.000 VNĐ PIRAMIDES EXTRA AT 15 160 mm 54 AT 15 28.314.000 VNĐ ROBUSTOS 25 124 mm 50 25 24.145.000 VNĐ ROBUSTOS 15 124 mm 50 AT 15 14.492.000 VNĐ MADURO SECRETOS 10 110 mm 40 10 5.869.000 VNĐ MADURO SECRETOS 25 110 mm 40 25 14.672.000 VNĐ SIGLO I 25 102 mm 40 25 10.940.000 VNĐ SIGLO I AT 15 102 mm 40 AT 15 9.266.000 VNĐ Name Lenght Ring Box Price SIGLO II 25 129 mm 42 CP 25 16.731.000 VNĐ SIGLO II 25 129 mm 42 25 16.731.000 VNĐ SIGLO III 25 155 mm 42 CP 25 20.798.000 VNĐ SIGLO IV 25 143 mm 46 25 25.225.000 VNĐ SIGLO IV 15 143 mm 46 AT 15 18.147.000 VNĐ SIGLO IV 25 143 mm 46 25 25.225.000 VNĐ SIGLO VI TUBOS 15 150 mm 52 AT 15 26.435.000 VNĐ SIGLO VI 25 150 mm 52 25 37.323.000 VNĐ TALISMAN 10 2017 LIMITED 154 mm 54 10 30.888.000 VNĐ Lenght 156 mm Lenght 124 mm Ring 52 mm Ring 50 mm Box Box COMBINACIONES SELECCION PIRAMIDES, 6'S COMBINACIONES SELECCION ROBUSTOS 6'S Romeo y Julieta, Cohiba, Hoyo de Monterrey, Cohiba Robusto, Montecristo Open Master, The Montecristo No. -

Session Name Page Number

56th AREUEA Annual Conference Virtual January 3-5, 2021 Session Name Page Number Sunday, January 03, 2021 10:00 AM-12:00 PM Real Estate Development 1 Virtual Session Search, Auctions, and Price Formation 2 Virtual Session Securitization 3 Virtual Session 12:15 PM-02:15 PM Affordable Housing 4 Virtual Session Real Estate and Technology 5 Virtual Session Real Estate Intermediaries 6 Virtual Session 03:45 PM-05:45 PM Home Ownership 7 Virtual Session REITs 8 Virtual Session Monday, January 04, 2021 10:00 AM-12:00 PM COVID-19 9 Virtual Session House Prices 10 Virtual Session 12:15 PM-02:15 PM International Real Estate and Institutions 11 Virtual Session Migration and Housing 12 Virtual Session Mortgages and Housing Policy 13 Virtual Session 56th AREUEA Annual Conference Virtual January 3-5, 2021 Session Name Page Number Monday, January 04, 2021 02:30 PM-03:30 PM AREUEA Presidential Address Virtual Address 03:45 PM-05:45 PM AREUEA-AFA Joint Session: Real Estate Finance 14 Virtual Session Public Policy 15 Virtual Session Tuesday, January 05, 2021 10:00 AM-12:00 PM Housing Wealth and Consumption 16 Virtual Session Machine Learning 17 Virtual Session 12:15 PM-02:15 PM Corporate Finance and Real Estate 18 Virtual Session ESG and Climate Change 19 Virtual Session Reverse Mortgages 20 Virtual Session 03:45 PM-05:45 PM Housing and Inequality 21 Virtual Session Real Estate Taxation 22 Virtual Session Transportation 23 Virtual Session 56th AREUEA Annual Conference Virtual January 3-5, 2021 56th AREUEA Annual Conference Virtual January 3-5, 2021 SESSION -

Diplomatic List – Fall 2018

United States Department of State Diplomatic List Fall 2018 Preface This publication contains the names of the members of the diplomatic staffs of all bilateral missions and delegations (herein after “missions”) and their spouses. Members of the diplomatic staff are the members of the staff of the mission having diplomatic rank. These persons, with the exception of those identified by asterisks, enjoy full immunity under provisions of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations. Pertinent provisions of the Convention include the following: Article 29 The person of a diplomatic agent shall be inviolable. He shall not be liable to any form of arrest or detention. The receiving State shall treat him with due respect and shall take all appropriate steps to prevent any attack on his person, freedom, or dignity. Article 31 A diplomatic agent shall enjoy immunity from the criminal jurisdiction of the receiving State. He shall also enjoy immunity from its civil and administrative jurisdiction, except in the case of: (a) a real action relating to private immovable property situated in the territory of the receiving State, unless he holds it on behalf of the sending State for the purposes of the mission; (b) an action relating to succession in which the diplomatic agent is involved as an executor, administrator, heir or legatee as a private person and not on behalf of the sending State; (c) an action relating to any professional or commercial activity exercised by the diplomatic agent in the receiving State outside of his official functions. -- A diplomatic agent’s family members are entitled to the same immunities unless they are United States Nationals. -

Online Vintage Cigar Auction

Online Vintage Cigar Auction www.onlinecigarauctions.co.uk 11th June, 2017 2:00 P.M. I am delighted to present our Summer cigar auction catalogue. This is an online only auction sale. Bids can also be entered by email to [email protected] or by fax to +44 207 604 3983. Viewings are available by appointment at our London offices Monday - Friday 10 a.m. till 5 p.m. Our catalogue has a fine range of aged, mature, vintage, limited edition, pre embargo, Davidoff and Dunhill cigars. A comprehensive selection of cigars for the smoker as well as the collector. For any advice regarding this or future auctions please email us at [email protected] Our next auction is being planned for the December but I would remind prospective buyers and sellers that we buy and sell vintage Havana cigars throughout the year and are always happy to provide free valuations and sales advice. Mitchell Orchant Managing Director / VINTAGE CIGAR SPECIALIST C.GARS LTD CIGAR AUCTIONS cigar auction - June 2017 1 Buying at C.Gars Auctions and Conditions of Sale Mitchell Orchant, Laura Graham and our Sales Team will be pleased to answer any questions by email to [email protected] or phone 020 7372 1865. We strongly advise prospective bidders to contact us with any questions and queries before the auction as when a bid is successful a binding contract is formed. Please Note: All bidders must be over the age of 18. It is illegal to sell tobacco products to anyone under the age of 18. -

Habanos-News-1609

N or th er n Eu ro pe QUINTERO TUBULARES Habanos, S.A. presents the new Quintero Tubulares a new vitola incorporated to the most popular brand with origin in the city of Cienfuegos.Quintero Tubulares will be arriving to the all points of sales worldwide in the coming weeks. This is the first time that the brand is in aluminum tube. All the Quintero Habanos are made with leaves coming from Vuelta Abajo (D.O.P)* and Semi Vuelta zones, in the Pinar del Río (D.O.P.)* region. These Habanos are characterized by its medium bodied flavour. The Quinteros also are made “ Totalmente a Mano con Tripa Corta” Totally hand - made with short filler, a technique less used but recognized by the Regulatory Council for the Protected Denomination of Origin (D.O.P.) . For Quinteros blend el Torcedor (the roller) combines with chopped tobaccos leaves and rolls the filler into full- length binder leaves with the aid of a flexible mat fixed to form a firm bunch. The wrapper is applied by hand in the normal fashion. Quintero Tubulares is also introduced with a new presentation in aluminium tube. Quintero Tubulares 3x5p 133 x 16,67 mm • Ring Gauge 42 ROMEO Y JULIETA Romeo y Julieta’s balanced and aromatic blend of selected filler and binder leaves from the Vuelta Abajo zone make it the classic medium bodied Habano. Today Romeo y Julieta is as well known around the world as ever and offers the widest range of Tripa Larga, Totalmente a Mano – long filler, totally hand made – sizes available in any Habano brand. -

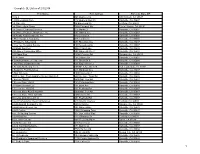

Complete BL List As of 2/1/2014

Complete BL List as of 2/1/2014 Firm Name Firm Address Firm City State ZIP 10 ta 2 343 Danbury Cir VACAVILLE, CA 95687 1-800-Leggings.Com 112 Hunters Glen Ct Vacaville, CA 95687 1st Care 4 U 84 Barcelona Cir Fairfield, CA 94533 1st Choice Auto Glass 7958 Claypool Wy Citrus Heights, CA 95610 1st Choice Cleaning Services 275 Marna Dr Vacaville, CA 95687 1st Choice Pressure Washers, LLC. 197 Albany Ave Vacaville, CA 95687 1st Realty And Investment, Inc 840 Lovers Ln Vacaville, CA 95688 2 Phat Dawgs & Company 818 Landon Ct Vacaville, CA 95688 2 Prosper U Advertising 253 Riverdale Ave Vacaville, CA 95687 2 The Tee Cleaning Service 160 Arrowhead Dr Vacaville, CA 95687 29 Glass Services 4542 Craig Lane Vacaville, CA 95688 292 Alamo Counseling Office 292 Alamo Dr Ste 3 Vacaville, CA 95688 3-D Signs Plus 10060 Calvine Rd Sacramento, CA 95829 3S A Charm 1642 Alamo Dr Vacaville, CA 95687 4 Caminos Market Y Taqueria 111 Brown St B Vacaville, CA 95688 4 Our Play & Entertainment 625 Eagle River Ct Vacaville, CA 95688 4 Results Marketing L L C 100 NE 3 Ave Ste 610 Fort Lauderdale, FL 33301 4 Season's Pool Services 218 Mariposa Ave Vacaville, CA 95687 5 Star Wireless 1990 Alamo Dr 3 Vacaville, CA 95688 6801 Leisure Town Apartments Investors LLC 6801 Leisure Town Rd Vacaville, CA 95688 7 Eleven #22837 2490 Nut Tree Rd Vacaville, CA 95687 7 Eleven Store 23433 189 S Orchard Ave Vacaville, CA 95688 784 Buck Avenue LLC 784 Buck Ave Vacaville, CA 95688 7-Eleven Inc. -

In the Next Cigar Insider

internet only CigarMAY 01, 2012 n VOL. 17, NO.Insider 9 n FROM THE PUBLISHER OF CIGAR AFICIONADO MAGAZINE CLICK HERE TO SUBSCRIBE IN THIS ISSUE: FEATURED CIGAR PADRÓN FAMILY RESERVE TASTING REPORT: 85 YEARS NATURAL VERTICAL BRAND TASTINGS: NICARAGUA n PRICE: $20.00 n BODY: MEDIUM 93 POINTS For a full tasting, see page three. n Gurkha Royal Challenge [page 2] n Berger & Argenti Entubar CRV [page 2] BEST CIGARS THIS ISSUE NEW SIZES: Padrón Family Reserve 85 Years Natural Nicaragua 93 n Padrón Family Reserve 85 Years Natural [page 3] Punch Clásicos Exclusivo Suiza Cuba 90 n Punch Clásicos Exclusivo Suiza [page 3] Berger & Argenti Entubar CRV Corona Macho Nicaragua 89 Berger & Argenti Entubar CRV Double Corona Nicaragua 89 CIGAR NEWS Berger & Argenti Entubar CRV Robusto Nicaragua 89 n Night To Remember: Cigar Aficionado Charity Dinner Raises More Than $1 Million [page 4] Berger & Argenti Entubar CRV Toro Nicaragua 89 n Fake Cohibas Seized in Miami [page 6] Gurkha Royal Challenge, Four Tied At Nicaragua 87 n Petition Garners 25,000 Signatures to Keep FDA Away From Premium Cigars [page 6] n Storms Ravage Tobacco Crops [page 6] WEATHER V. TOBACCO n Limited Decade From Rocky Patel [page 7] BAD WEATHER IS THE BANE OF TOBACCO FARMERS. A freak hailstorm in n Aging Room Brand Expands [page 7] northern Nicaragua on April 21 destroyed a field of leaves (see photo) meant to go around Padrón n New Size For Cuban Quintero Brand [page 8] cigars. It’s the latest chapter in the never-ending battle between the weather and the men who farm tobacco. -

Webb County Accounts Payable Check Register December 2019

Webb County Accounts Payable Check Register December 2019 Transaction Transaction Departmental Department TransactionType Payee Item Description Itemized Amount Fund Number Date Amount 111th District Court Check 8403 12/02/2019 BUILDING BRIDGES $1,125.00 COURT INTERPRETATION $1,125.00 General Fund LANGUAGE SVCS 8410 12/02/2019 DON PABLOS $118.34 BREAKFAST FOR JURY 111TH DIST CRT $118.34 General Fund RESTAURANT 8434 12/02/2019 SAM'S CLUB DIRECT $180.00 coca cola item # 980012379 $22.84 General Fund forks Item # 195020 $10.98 General Fund frito lay classic mix Item # 980172993 $25.96 General Fund hefty supreme plates Item # 361387 $12.88 General Fund kar sweet n salty mix Item # 980101300 $12.98 General Fund Member’s Mark Soft & Strong Facial $21.96 General Fund Tissues, 12 Flat Boxes, 160 2 Member's Mark 1-Ply Everyday White $20.56 General Fund Napkins, 11.4" x 12.5" (4 pk. nabisco classic mix Item # 475353 $22.72 General Fund spoons Item # 195027 $10.98 General Fund sprite Item # 980012387 $11.42 General Fund water Item # 980002151 $6.72 General Fund 8435 12/02/2019 SOUTH TEXAS FORENSIC $600.00 Indigent Defense $600.00 General Fund PSYCHOLOGY PLLC 8608 12/04/2019 DON PABLOS $115.85 BREAKFAST FOR GRAND JURY 111TH $115.85 General Fund RESTAURANT DIST CRT 8741 12/05/2019 DEL RIO LAW FIRM PLLC $11,043.75 Indigent Defense $11,043.75 General Fund 8752 12/05/2019 JIMMY JOHNS $252.98 FOOD FOR JURY TRIAL 111TH DIST CRT $252.98 General Fund 8776 12/05/2019 RAUL CASSO IV LAW PLLC $300.00 Family Case $300.00 General Fund 8781 12/05/2019 SOUTH TEXAS -

Prices Are in Thai Baht and Are Subject to 10% Service Charge Plus Applicable Tax Please Inquire with Senior Management If You H

Prices are in Thai Baht and are subject to 10% service charge plus applicable tax Please inquire with senior management if you have any dietary restriction, allergies or special considerations. Signature Cocktail The Forbidden Fruit Henessy VSOP, Amaretto, Lime, Honey, Cinnamon powder, Apple Cider 490 Venus Elixir Hendricks Gin, Roselle syrup, grapefruit juice, lime, rose water, rose flower 450 Age Craft Cocktail Cocktails inspired from locally sourced ingredients Rebirth of the Spritz AGE infused bitter rum, secret spices syrup, Ginger liqueur, Umeshu liqueur, Prosecco, Soda 450 Tropical Essences Phraya Thai Rum, Galliano Vanilla Liqueur, Coconut Nectar, dry palm sugar, kaffir lime, lime, coconut liqueur 490 3’o’clock Julep Bourbon infused with Thai tea, jasmine tea syrup, egg white, lime 490 Our bartenders are very happy to create any other classic cocktails upon request Prices are in Thai Baht and are subject to 10% service charge plus applicable tax Please inquire with senior management if you have any dietary restriction, allergies or special considerations. Age Classic Unbeatable classics, Age version AGE Negroni Coffee-Tonka infused gin, Campari, Kahlua, Angostura bitter 420 AGE Margarita Tequila, Triple Sec, Lime, Flamed Pineapple compote, Spicy infused salt 450 AGE Cosmopolitan Black rice infused vodka, Triple Sec, Chambord liqueur, Lime, Cranberry juice 420 Signature Age Gin Experience Mediterranean journey Gin Mare, Rosemary Syrup, fresh rosemary, pomegranate, lime, pomegranate and basil Premium Soda 590 Asian Journey Iron