Charlotte Brontë's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Men, Women, and Property in Trollope's Novels Janette Rutterford

Accounting Historians Journal Volume 33 Article 9 Issue 2 December 2006 2006 Frank must marry money: Men, women, and property in Trollope's novels Janette Rutterford Josephine Maltby Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aah_journal Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation Rutterford, Janette and Maltby, Josephine (2006) "Frank must marry money: Men, women, and property in Trollope's novels," Accounting Historians Journal: Vol. 33 : Iss. 2 , Article 9. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aah_journal/vol33/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Archival Digital Accounting Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Accounting Historians Journal by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rutterford and Maltby: Frank must marry money: Men, women, and property in Trollope's novels Accounting Historians Journal Vol. 33, No. 2 December 2006 pp. 169-199 Janette Rutterford OPEN UNIVERSITY INTERFACES and Josephine Maltby UNIVERSITY OF YORK FRANK MUST MARRY MONEY: MEN, WOMEN, AND PROPERTY IN TROLLOPE’S NOVELS Abstract: There is a continuing debate about the extent to which women in the 19th century were involved in economic life. The paper uses a reading of a number of novels by the English author Anthony Trollope to explore the impact of primogeniture, entail, and the mar- riage settlement on the relationship between men and women and the extent to which women were involved in the ownership, transmission, and management of property in England in the mid-19th century. INTRODUCTION A recent Accounting Historians Journal article by Kirkham and Loft [2001] highlighted the relevance for accounting history of Amanda Vickery’s study “The Gentleman’s Daughter.” Vickery [1993, pp. -

Trollopiana 100 Free Sample

THE JOURNAL OF THE Number 100 ~ Winter 2014/15 Bicentenary Edition EDITORIAL ~ 1 Contents Editorial Number 100 ~ Winter 2014-5 his 100th issue of Trollopiana marks the beginning of our FEATURES celebrations of Trollope’s birth 200 years ago on 24th April 1815 2 A History of the Trollope Society Tat 16 Keppel Street, London, the fourth surviving child of Thomas Michael Helm, Treasurer of the Trollope Society, gives an account of the Anthony Trollope and Frances Milton Trollope. history of the Society from its foundation by John Letts in 1988 to the As Trollope’s life has unfolded in these pages over the years present day. through members’ and scholars’ researches, it seems appropriate to begin with the first of a three-part series on the contemporary criticism 6 Not Only Ayala Dreams of an Angel of Light! If you have ever thought of becoming a theatre angel, now is your his novels created, together with a short history of the formation of our opportunity to support a production of Craig Baxter’s play Lady Anna at Society. Sea. During this year we hope to reach a much wider audience through the media and publications. Two new books will be published 7 What They Said About Trollope At The Time Dr Nigel Starck presents the first in a three-part review of contemporary by members: Dispossessed, the graphic novel based on John Caldigate by critical response to Trollope’s novels. He begins with Part One, the early Dr Simon Grennan and Professor David Skilton, and a new full version years of 1847-1858. -

The Hobbledehoy's Choice

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 The hobbledehoy's choice: Anthony Trollope's awkward young men and their road to gentlemanliness Mark King Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation King, Mark, "The hobbledehoy's choice: Anthony Trollope's awkward young men and their road to gentlemanliness" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3930. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3930 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE HOBBLEDEHOY S CHOICE: ANTHONY TROLLOPE S AWKWARD YOUNG MEN AND THEIR ROAD TO GENTLEMANLINESS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Mark King B.S., Towson State University, 1983 M.A., DePaul University, 1998 May 2005 Dedication To Bear and all the other women who never lost faith in their hobbledehoys. ii Acknowledgements The author gratefully acknowledges the contributions of the following organizations and individuals without whose generous support and kind help this work would not have been possible: the staff of the Hill Memorial Library at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge, the staff of the John Forster collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the staff of the Interlibrary Loan Office of the Troy Middleton Library at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge, the staff of the Rare Books Room of the British Library in London, Dr. -

The Three Clerks Trollope, Anthony

The Three Clerks Trollope, Anthony Published: 1857 Categorie(s): Fiction, Literary, Biographical Source: http://gutenberg.org 1 About Trollope: Anthony Trollope's father, Thomas Anthony Trollope, worked as a barrister. Thomas Trollope, though a clever and well-edu- cated man and a Fellow of New College, Oxford, failed at the bar due to his bad temper. In addition, his ventures into farm- ing proved unprofitable and he lost an expected inheritance when an elderly uncle married and had children. Nonetheless, he came from a genteel background, with connections to the landed gentry, and so wished to educate his sons as gentlemen and for them to attend Oxford or Cambridge. The disparity between his family's social background and its poverty would be the cause of much misery to Anthony Trollope during his boyhood. Born in London, Anthony attended Harrow School as a day-boy for three years from the age of seven, as his father's farm lay in that neighbourhood. After a spell at a private school, he followed his father and two older brothers to Winchester College, where he remained for three years. He re- turned to Harrow as a day-boy to reduce the cost of his educa- tion. Trollope had some very miserable experiences at these two public schools. They ranked as two of the most élite schools in England, but Trollope had no money and no friends, and got bullied a great deal. At the age of twelve, he fantasized about suicide. However, he also daydreamed, constructing elaborate imaginary worlds. In 1827, his mother Frances Trollope moved to America with Trollope's three younger sib- lings, where she opened a bazaar in Cincinnati, which proved unsuccessful. -

'A Mere Clerk': Representing the Urban Lower-Middle-Class

‘A MERE CLERK’: REPRESENTING THE URBAN LOWER-MIDDLE-CLASS MAN IN BRITISH LITERATURE AND CULTURE: 1837-1910. DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Scott Douglass Banville, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Approved by Dissertation Committee: Professor David G. Riede, Adviser Adviser Professor Clare Simmons English Graduate Program Professor Amanpal Garcha ABSTRACT My dissertation explores the various ways in which the lower middle class is represented in the Victorian period. Drawing on literary texts by Charles Dickens, Anthony Trollope, and George Gissing and non-literary texts appearing in periodicals, comic newspapers, and music-hall songs I show how the lower middle class consisting of those members of British society working variously as Civil Service, commercial, and retail clerks, school teachers, and living in the suburbs of London and other large cities is represented as dangerous, laughable, and pitiable. Through readings of self-improvement books by Samuel Smiles, conduct and instruction manuals, and didactic literature I show how middle-class anxieties about its own position vis-à-vis the aristocracy and the working class drive middle-class elites and its representatives to represent the lower middle class as dangerous and thus in need of containment and surveillance. One of the constant fears of the middle class is that the lower middle class will develop a cultural and economic identity of its own and as a result will over shadow the middle class. Often times this middle-class anxiety is cloaked in moral concern. -

Anthony Trollope*S Literary Reputation;

ANTHONY TROLLOPE*S LITERARY REPUTATION; ITS DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDITY by ELLA KATHLEEN GRANT A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for. the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English The University of British Columbia, October, 1950. This essay attempts to trace the course of Anthony Trollope's literary reputation; to suggest some explan• ations for the various spurts and sudden declines of his popularity among readers and esteem among critics; and to prove that his mid-twentieth century position is not a just one. Drawing largely on Trollope's Autobiography, contemp• orary reviews and essays on his work, and references to it in letters and memoirs, the first chapter describes Trollope's writing career, showing him rising to popu• larity in the late fifties and early sixties as a favour• ite among readers tired of sensational fiction, becoming a byword for commonplace mediocrity in the seventies, and finally, two years before his death, regaining much of his former eminence among older readers and conservative critics. Throughout the chapter a distinction is drawn between the two worlds with which Trollope deals, Barset- shire and materialist society, and the peculiarly dual nature of his work is emphasized. Chapter II is largely concerned with the vicissitudes that Trollope's reputation has encountered since the post• humous publication of his autobiography. During the de• cade following his death he is shown as an object of comp• lete contempt to the Art for Art's Sake school, finally rescued around the turn of the century by critics reacting against the ideals of his detractors. -

The Lawyers of Anthony Trollope

The Lawyers of Anthony Trollope By Henry S. Drinker British novelist Anthony Trollope (1815–1882) wrote, in addition to 47 novels, an autobiogra- phy, a book on Thackeray, five travel books, and 42 short stories. Henry S. Drinker (1880–1965) was a partner in the law firm of Drinker Biddle and was also a musicologist. The essay that follows was an address delivered to members of the Grolier Club in New York City on Nov. 15, 1949. It is presented as it was published by the Grolier Club in 1950, in a book en- titled Two Addresses Delivered to Members of the Grolier Club; the other essay that appears in the book is “Trollope’s America” by Willard Thorp. Only 750 copies of the book were printed. hen I received the delightful invitation to speak Trollope was—perhaps I should say he became—an on Trollope—one of my chief enthusiasms—it extraordinarily careful observer of what was passing was immediately clear to me that my subject around him, and his genius lay in his ability to re-create, must be his lawyers; first, because, as a lawyer, I should with convincing vividness, the types of people whom he Wthus be able to make a more valuable contribution to the observed wherever he chanced to be. He did not create growing store of comment on his writings, and, second, his characters with any desire to point a moral, nor did he because I believe that Trollope’s ideas about and attitude use them as a medium for expressing his own ideas or toward lawyers have not been understood or appreciated epigrams. -

Autobiography of Anthony Trollope

Autobiography of Anthony Trollope Anthony Trollope Autobiography of Anthony Trollope Table of Contents Autobiography of Anthony Trollope.......................................................................................................................1 Anthony Trollope...........................................................................................................................................1 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER I. MY EDUCATION 1815−1834...............................................................................................3 CHAPTER II. MY MOTHER.......................................................................................................................8 CHAPTER III. THE GENERAL POST OFFICE 1834−1841....................................................................12 CHAPTER IV. IRELANDMY FIRST TWO NOVELS 1841−1848........................................................20 CHAPTER V. MY FIRST SUCCESS 1849−1855......................................................................................26 CHAPTER VI. "BARCHESTER TOWERS" AND THE "THREE CLERKS" 1855−1858......................32 CHAPTER VII. "DOCTOR THORNE""THE BERTRAMS""THE WEST INDIES" AND "THE SPANISH MAIN".......................................................................................................................................37 CHAPTER VIII. THE "CORNHILL MAGAZINE" AND "FRAMLEY PARSONAGE".........................41 -

The Hobbledehoy's Choice: Anthony Trollope's Awkward Young Men And

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Louisiana State University Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 The hobbledehoy's choice: Anthony Trollope's awkward young men and their road to gentlemanliness Mark King Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation King, Mark, "The hobbledehoy's choice: Anthony Trollope's awkward young men and their road to gentlemanliness" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3930. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3930 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE HOBBLEDEHOY S CHOICE: ANTHONY TROLLOPE S AWKWARD YOUNG MEN AND THEIR ROAD TO GENTLEMANLINESS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Mark King B.S., Towson State University, 1983 M.A., DePaul University, 1998 May 2005 Dedication To Bear and all the other women who never lost faith in their hobbledehoys. -

Appendix II Bibliography of Anthony Trollope

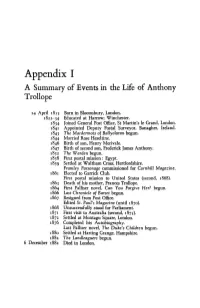

Appendix I A Summary of Events in the Life of Anthony Trollope 24 April 1815 Born in Bloomsbury, London. 1822-34 Educated at Harrow; Winchester. 1834 Joined General Post Office, StMartin's le Grand, London. 1841 Appointed Deputy Postal Surveyor, Banagher, Ireland. 1843 The Macdermots of Ballycloran begun. 1844 Married Rose Heseltine. 1846 Birth of son, Henry Merivale. 1847 Birth of second son, Frederick James Anthony. 1852 The Warden begun. 1858 First postal mission: Egypt. 1859 Settled at Waltham Cross, Hertfordshire. Framley Parsonage commissioned for Cornhill Magazine. 1861 Elected to Garrick Club. First postal mission to United States (second, 1868). 1863 Death of his mother, Frances Trollope. 1864 First Palliser novel, Can You Forgive Her? begun. 1866 Last Chronicle of Barset begun. 1867 Resigned from Post Office. Edited St. Paul's Magazine (until187o). 1868 Unsuccessfully stood for Parliament. 1871 First visit to Australia (second, 1875). 1872 Settled at Montagu Square, London. 1876 Completed his Autobiography. Last Palliser novel, The Duke's Children begun. 188o Settled at Harting Grange, Hampshire. 1882 The Landleagu.ers begun. 6 December 1882 Died in London. Appendix II Bibliography of Anthony Trollope (i) MAJOR WORKS The Macdermots of Ballydoran, 3 vols, London: T. C. Newby, 1847 [abridged in one volume, Chapman & Hall's 'New Edition', 1861]. The Kellys and the O'Kellys: or Landlords and Tenants, 3 vols, London: Henry Colburn, 1848. La Vendee: An Historical Romance, 3 vols, London: Colburn, 185o. The Warden, 1 vol, London: Longman, 1855. Barchester Towers, 3 vols, London: Longman, 1857. The Three Clerks: A Novel, 3 vols, London: Bentley, 1858. -

The Journal of The

THE JOURNAL OF THE Number 107 ~ Summer 2017 Trollope’s Legal Mistakes in ‘The Great Orley Farm Case’ – Can You Forgive Him? Todd Shields EDITORIAL ~ 1 Contents Editorial Number 107 ~ Summer 2017 FEATURES e are delighted to include in this edition of Trollopiana an interview with actress Susan Hampshire, famous amongst 2 An Interview with Susan Hampshire Trollopians for her roles as Lady Glencora and Madeline Actress Susan Hampshire talks about her career and specifically about W playing Lady Glencora and Madeline Neroni in BBC adaptations of Neroni in BBC adaptations of Trollope’s novels. Susan has long been Trollope’s novels. a supporter of the Society and has recently agreed to become on of our Vice Presidents, so the interview, with insights into her experiences 8 Trollope’s Legal Mistakes in ‘The Great Orley Farm playing these roles, is timely. Case’ – Can You Forgive Him? Todd Shields We are also very pleased to include two further items from the Texas based lawyer Todd Shields has been a devoted Trollopian since meeting in London last year which focussed on Trollope and the the early 1990s. He considers whether criticism of Trollope’s treatment Law. Society member Todd Shields, a practising lawyer from the of the law in Orley Farm was justified. United States provides a spirited defence of Trollope’s depiction of his profession in Orley Farm, which provoked outraged criticism from 20 What Muriel Rose Remembered - Part Three lawyers not just at the time of its publication in 1862 but also when it Trollope Society Chair, Michael Williamson, explores more of what Muriel Rose, Anthony Trollope’s grand-daughter remembered. -

Anthony Trollope Between Britain and Ireland

Writing the Frontier Anthony Trollope between Britain and Ireland JOHN McCOURT 2015 1 Contents Abbreviations for Trollope editions used in this text (these editions are not re-listed in the bibliography) xi 1. Introduction: Anthony Trollope between Britain and Ireland 1 2. Questions of Justice in the Early Irish Novels 54 3. Trollope and the Famine 96 4. A Question of Character—The Many Lives of Phineas Finn 138 5. Gentlemen Priests and Rebellious Curates: Trollope’s Irish Catholic Clergy 175 6. Problems of Form: Trollope’s Irish Short Stories 202 7. Trollope’s Irish English 222 8. Countering Rebellion 235 9. Afterword: Irish Letters 276 Bibliography 287 Index 305 Abbreviations for Trollope editions used in this text (these editions are not re-listed in the bibliography) Trollope works Auto An Autobiography, 1883. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. Bertrams The Bertrams, 1859. London: Chapman & Hall, 1859. BJR The Struggles of Brown, Jones and Robinson, 1862. London Penguin, 1993. BT Barchester Towers, 1857. London: Penguin, 1994. Clarissa ‘Clarissa’, Saint Pauls Magazine, November 1868, 163–72. CR Castle Richmond, 1859. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989. CSF Julian Thompson, ed. The Complete Shorter Fiction. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1992. CYFH Can You Forgive Her?, 1864. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. Duke’s Children The Duke’s Children, 1880. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011. Eustace Diamonds The Eustace Diamonds, 1873. London: Penguin, 1986. Examiner Helen Garlinghouse King, ed. ‘Trollope’s Letters to the Examiner’, The Princeton University Library Chronicle, 26/2 (Winter 1965), 71–101. EYE An Eye for An Eye, 1879. London: The Folio Society, 1993.