Administrative Justice in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supreme Court Visit to NUI Galway 4-6 March, 2019 Welcoming the Supreme Court to NUI Galway

Supreme Court Visit to NUI Galway 4-6 March, 2019 Welcoming the Supreme Court to NUI Galway 4-6 March, 2019 Table of Contents Welcome from the Head of School . 2 Te School of Law at NUI Galway . 4 Te Supreme Court of Ireland . 6 Te Judges of the Supreme Court . 8 2 Welcome from the Head of School We are greatly honoured to host the historic sittings of the Irish Supreme Court at NUI Galway this spring. Tis is the frst time that the Supreme Court will sit outside of a courthouse since the Four Courts reopened in 1932, the frst time the court sits in Galway, and only its third time to sit outside of Dublin. To mark the importance of this occasion, we are running a series of events on campus for the public and for our students. I would like to thank the Chief Justice and members of the Supreme Court for participating in these events and for giving their time so generously. Dr Charles O’Mahony, Head of School, NUI Galway We are particularly grateful for the Supreme Court’s willingness to engage with our students. As one of Ireland’s leading Law Schools, our key focus is on the development of both critical thinking and adaptability in our future legal professionals. Tis includes the ability to engage in depth with the new legal challenges arising from social change, and to analyse and apply the law to developing legal problems. Te Supreme Court’s participation in student seminars on a wide range of current legal issues is not only deeply exciting for our students, but ofers them an excellent opportunity to appreciate at frst hand the importance of rigorous legal analysis, and the balance between 3 necessary judicial creativity and maintaining the rule of law. -

Nui Honorary Degrees Awarded

NUI HONORARY DEGREES AWARDED Note 1: The graduates listed below obtained honorary doctorates from the Royal University of Ireland in or before the year 1909, and subsequently registered as graduates of the National University of Ireland. Adeney, Walter E DSc 1897 Anderson, Alexander, DSc 1909 BA, 1880; MA, 1881 Byrne, Very Rev. Peter LLD 1909 Cameron, Sir Charles A, MD 1896 CB Cochrane, Robert LLD 1905 Conway, Arthur W., BA, DSc 1908 1896; MA, 1897; FRS D’Alton, Very Rev. LLD 1909 Edward A., Canon Delany, Very Rev LLD 1885 William Flood, William H. G. DMus 1907 Healy, His Grace the DLitt 1885 Most Rev John Hogan, Rev Edmund DLitt 1897 Hyde, Douglas, (first DLitt 1906 President of Ireland) LLD University of Dublin McClelland, John, BA DSc 1906 1892, MA 1893, FRS McGrath, Sir Joseph LLD 1892 Pye, Joseph P., MD, DSc 1882 MCh 1871 Senier, Alfred DSc 1908 Windle, Sir Bertram LLD 1907 C.A., FRS Note 2: The Senate of the newly founded National University of Ireland awarded honorary doctorate degrees on the persons listed below; they had attended the Catholic University of Ireland for conscientious reasons, but the Catholic University did not have the authority to award degrees. Bodkin, His Honour Judge LLD 1915 Mathias McDonnell Cannon, Richard MD 1915 Connolly, Nicholas T. LLD 1915 Creagh, William LLD 1915 Crean, Lt.-Col. John Joseph LLD 1915 Crean, Thomas J. MD 1915 Cuffe, Surgeon-General Sir LLD 1915 Charles McD, KCB Dawson, Charles LLD 1915 De La Pasture, Rev. Charles LLD 1915 E, SJ Dillon, Rev. Henry, OFM LLD 1915 Dillon, William LLD 1915 Fottrell, John G. -

Address of the Hon. Mr Justice Frank Clarke, Chief Justice of Ireland, to the Law Reform

Address of The Hon. Mr Justice Frank Clarke, Chief Justice of Ireland, to the Law Reform Commission Annual Conference, November 2017 ____________ Firstly can I thank the President for the opportunity to do the one thing I have wanted all my life; that is to be the warm up act for Michael McDowell and Dearbhail McDonald. Those who are old enough will remember that, in a previous life, one John Quirke was a quite distinguished scrum half in rugby who represented Leinster and occasionally Ireland. So I feel now like the out-half who has just been passed the ball by the nippy scrumhalf and I have to make a number of decisions. Do I deploy the hard-running of inside-centre McDowell; or the silkier skills of outside-centre McDonald; or do I try and go for a run on my own; or do I put up a Garryowen and throw up a few ideas and see where they land. I will leave it up to you at the end of my address to determine which of these plays I have decided to deploy. I would like to do two things. First, I hope to make some general observations on where we are at in relation to law reform, particularly so far as it affects the courts, as that is the day job and it is my job to consider these matters in relation to the courts; and second, to seek to apply those general observations to a number of areas which might benefit from future research on the part of the Law Reform Commission. -

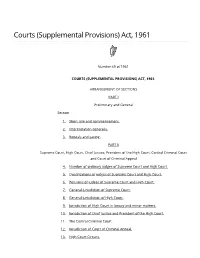

Courts (Supplemental Provisions) Act, 1961 (Act No. 39 of 1961)

Courts (Supplemental Provisions) Act, 1961 Number 39 of 1961. COURTS (SUPPLEMENTAL PROVISIONS) ACT, 1961. ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I Preliminary and General Section 1. Short title and commencement. 2. Interpretation generally. 3. Repeals and saving. PART II Supreme Court, High Court, Chief Justice, President of the High Court, Central Criminal Court and Court of Criminal Appeal 4. Number of ordinary judges of Supreme Court and High Court. 5. Qualifications of judges of Supreme Court and High Court. 6. Pensions of judges of Supreme Court and High Court. 7. General jurisdiction of Supreme Court. 8. General jurisdiction of High Court. 9. Jurisdiction of High Court in lunacy and minor matters. 10. Jurisdiction of Chief Justice and President of the High Court. 11. The Central Criminal Court. 12. Jurisdiction of Court of Criminal Appeal. 13. High Court Circuits. 14. Jurisdiction to be exercised pursuant to rules of court (Supreme Court, High Court, Chief Justice, President of the High Court, Central Criminal Court and Court of Criminal Appeal). PART III Circuit Court 15. Definitions (Part III). 16. Number of ordinary judges of Circuit Court. 17. Qualifications of judges of Circuit Court. 18. Age of retirement of judge of Circuit Court. 19. Pensions of judges of Circuit Court. 20. Circuits and assignment of judges to circuits. 21. Circuit Court to be a court of record. 22. Jurisdiction of Circuit Court, except in applications for new on-licences and in indictable offences. 23. Jurisdiction of Cork Circuit Court Judge in admiralty causes and in bankruptcy. 24. Jurisdiction of Circuit Court in applications for new on-licences. -

Legal Costs in Ireland: Who Pays? the Laws and Principles and Comparative Considerations

LEGAL COSTS IN IRELAND: WHO PAYS? THE LAWS AND PRINCIPLES AND COMPARATIVE CONSIDERATIONS Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Anglia Ruskin University by Jevon Alcock (LL.M, Solicitor and Notary Public) Faculty of Arts, Law and Social Sciences, Anglia Ruskin University February 2019 Resubmission April 2020 Supervised by: Mr. Thomas Serby, Dr. Stefan Mandelbaum, Dr. Aldo Zammit-Borda. Acknowledgements I wish to express my gratitude to Mr David J. O’Hagan, former Chief State Solicitor, Dublin, Ireland who nominated me to serve on various committees and working groups on legal costs, which ignited my interest in this adjectival but pervasive area of law. I also wish to thank Dr. Desmond Hogan, and Mr Owen Wilson, Assistant Chief State Solicitors, both of whom supported my training and development. And, in this regard, I wish to acknowledge the financial assistance I received from the Chief State Solicitor’s Office towards my fees on the doctoral programme. Additionally, I wish to convey my thanks to Mr Brian Byrne, former Assistant Chief State Solicitor, who supported my admission as a solicitor in New South Wales, Australia, which in turn, ameliorated my legal knowledge and bolstered my capacity to perform comparative research. I wish to thank Mr Richard Walker, barrister-at-law, formerly head of the Commercial and Constitutional Litigation Section, who enabled me to secure experience across a broad swathe of subject areas, without which my capacity to undertake chapter 4 would have been fatally compromised. Moreover, I wish to thank Ms Karen Duggan, who as head of that section, ensured that I gained exposure to a broad cross-section of work. -

The Dublin and Monaghan Bombings

Tithe an Oireachtais An Comhchoiste um Dhlí agus Ceart, Comhionannas, Cosaint agus Cearta na mBan Tuarascáil Eatramhach maidir leis an Tuarascáil ón gCoimisiún Fiosrúcháin Neamhspleách faoi Bhuamáil Bhaile Átha Cliath agus Mhuineacháin Nollaig 2003 _________________________ Houses of the Oireachtas Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights Interim Report on the Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the Dublin and Monaghan Bombings December 2003 Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights Interim Report on the Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the Dublin and Monaghan Bombings CONTENTS Interim Report Pages 1 to 3 Appendices A. Orders of Reference and Powers of Joint Committee B. Membership of Joint Committee. C. Motions of the Dáil and Seanad D. Mr Justice Barron’s Statement to the Oireachtas Committee E. The Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the Dublin and Monaghan bombings Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights Interim Report on the Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the Dublin and Monaghan Bombings The Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights wishes to express it’s deepest sympathy with the victims and relatives of the victims of the Dublin and Monaghan bombings of 1974. As has been stated by Mr Justice Henry Barron, “the true cost of these atrocities in human terms is incalculable. In addition to the loss of innocent lives, hundreds more were scarred by physical and emotional injuries. The full story of suffering will never be known and it is ongoing in many cases. -

THE HISTORY and DEVELOPMENT of the SPECIAL CRIMINAL COURT 1922-2005” (Four Courts Press, 2007) Fergal Francis Davis

178 Judicial Studies Institute Journal [2009:1 BOOK REVIEW “THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE SPECIAL CRIMINAL COURT 1922-2005” (Four Courts Press, 2007) Fergal Francis Davis RONAN KEANE It is a melancholy reflection that, during the period of almost ninety years since the foundation of the State, the institution of the “special court” has been with us almost without interruption. As this exhaustive and thoughtful survey demonstrates, it has been present in a number of different forms, which have, however, one major feature in common: the assignment of at least some criminal trials of serious offences to tribunals sitting without a jury. Irrespective of one’s views on the merits of jury trials in criminal cases, the fact that successive governments and legislatures have considered it necessary to abrogate the right to them over so lengthy a period is, of itself, somewhat depressing. It can, of course, be said that the same period was dominated by the Civil War and its aftermath, the huge security problems of the Second World War, the “troubles” in Northern Ireland and, more recently, the growth of organised crime. That helps to explain the almost continuous recourse by successive executives to “special courts”, but is hardly of great comfort. Given that the distinguishing feature of these tribunals is the absence of the jury, it is understandable that Dr Davis at the outset should consider the arguments for and against the central role played by the jury in the Anglo-American criminal justice system. He is not fully persuaded by the arguments of those who, like de Tocqueville, see it as a valuable democratic process. -

To Manage the Courts, Support the Judiciary and Provide a High-Quality and Professional Service to All the Courts

THE COURTS SERVICE ANNUAL REPORT 2000 The Courts Service The effective operation of the courts system is a critical element of the well-being of any society. Courts, by virtue of their role, have a significant impact on lives and welfare. Their effectiveness is therefore of considerable importance. Effectiveness is not influenced solely by the manner in which cases are dealt with by judges in the courtroom environment, but also by the administrative and institutional framework which exists to support and facilitate the operation of the courts. In Ireland, this framework is provided by the Courts Service, which was established on 9 November, 1999 following on from the enactment of the Courts Service Act, 1998. Mission Statement To manage the courts, support the judiciary and provide a high-quality and professional service to all the courts 1 THE COURTS SERVICE ANNUAL REPORT 2000 The Courts Service The effective operation of the courts system is a critical element of the well-being of any society. Courts, by virtue of their role, have a significant impact on lives and welfare. Their effectiveness is therefore of considerable importance. Effectiveness is not influenced solely by the manner in which cases are dealt with by judges in the courtroom environment, but also by the administrative and institutional framework which exists to support and facilitate the operation of the courts. In Ireland, this framework is provided by the Courts Service, which was established on 9 November, 1999 following on from the enactment of the Courts Service Act, 1998. Mission Statement To manage the courts, support the judiciary and provide a high-quality and professional service to all the courts 1 THE COURTS SERVICE ANNUAL REPORT 2000 Foreword by the Chief Justice I am very pleased to write this foreword for this, The information contained in this Report, the first Annual Report of the Courts Service. -

Supreme Court Annual Report 2020

2020Annual Report Report published by the Supreme Court of Ireland with the support of the Courts Service An tSeirbhís Chúirteanna Courts Service Editors: Sarahrose Murphy, Senior Executive Legal Officer to the Chief Justice Patrick Conboy, Executive Legal Officer to the Chief Justice Case summaries prepared by the following Judicial Assistants: Aislinn McCann Seán Beatty Iseult Browne Senan Crawford Orlaith Cross Katie Cundelan Shane Finn Matthew Hanrahan Cormac Hickey Caoimhe Hunter-Blair Ciara McCarthy Rachael O’Byrne Mary O’Rourke Karl O’Reilly © Supreme Court of Ireland 2020 2020 Annual Report Table of Contents Foreword by the Chief Justice 6 Introduction by the Registrar of the Supreme Court 9 2020 at a glance 11 Part 1 About the Supreme Court of Ireland 15 Branches of Government in Ireland 16 Jurisdiction of the Supreme Court 17 Structure of the Courts of Ireland 19 Timeline of key events in the Supreme Court’s history 20 Seat of the Supreme Court 22 The Supreme Court Courtroom 24 Journey of a typical appeal 26 Members of the Supreme Court 30 The Role of the Chief Justice 35 Retirement and Appointments 39 The Constitution of Ireland 41 Depositary for Acts of the Oireachtas 45 Part 2 The Supreme Court in 2020 46 COVID-19 and the response of the Court 47 Remote hearings 47 Practice Direction SC21 48 Application for Leave panels 48 Statement of Case 48 Clarification request 48 Electronic delivery of judgments 49 Sitting in King’s Inns 49 Statistics 50 Applications for Leave to Appeal 50 Categorisation of Applications for Leave to Appeal -

11 Meeting of the Joint Council on Constitutional Justice Brno, Czech

Strasbourg, 29 June 2012 CDL-JU(2012)012 Engl. only EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) in co-operation with the CONSTITUTIONAL COURT OF THE CZECH REPUBLIC 11th meeting of the Joint Council on Constitutional Justice Brno, Czech Republic, 31 May – 1 June 2012 MINI-CONFERENCE ON “THE RULE OF LAW” REPORT by Mr Richard McNamara, Solicitor, Executive Legal Officer to the Chief Justice of Ireland, The Honourable Mrs. Justice Susan Denham his document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. www.venice.coe.int CDL-JU(2012)012 - 2 - Introduction Dobré odpoledne, dámy a pánové. Mesdammes et Messieurs. Good afternoon Ladies and Gentlemen. Before beginning, I thank the organisers of our Joint Council meeting and to our hosts at the Constitutional Court for the wonderful hospitality we have received here in Brno. I am delighted for the opportunity to speak about constitutional case law of the Supreme Court of Ireland which touches upon aspects of the Rule of Law. As the Executive Legal Officer to Ireland’s new Chief Justice, The Honourable Mrs. Justice Susan Denham, I bring greetings and good wishes on her behalf. The Rule of Law and some common law perspectives The concept of the Rule of Law has thankfully received greater scrutiny in recent years. The Report on the Rule of Law adopted by the Venice Commission in March of last year is a significant and timely document. It is an excellent resource which helps to give a better understanding of one of the three pillars of the Council of Europe, the others being democracy and human rights. -

Denis Riordan, Intended Plaintiff V. an Taoiseach

4 I.R. The Irish Reports 463 Denis Riordan, Intended Plaintiff v. An Taoiseach, An Tánaiste, Minister for Finance, Government of Ireland, Attorney General, Chief Justice of Ireland, President of the High Court and Ireland (No. 5) Intended Defendants [2001 No. 45 I.A.] High Court 11th May, 2001 Practice and procedure – Isaac Wunder order – Leave to issue proceedings – Whether claim frivolous or vexatious – Whether intended plaintiff had locus standi – Courts (Establishment and Constitution) Act, 1961 (No. 38), ss. 1(3) and (4), 2(3), (4) and (5) – Finance Act, 2001 (No. 7), s. 33 - Constitution of Ireland, 1937, Articles 34 to 36. Constitution – Locus standi – Right of access to courts – Restriction of right – Whether claim vexatious – Whether claim abuse of process of court. By order of the High Court, the intended plaintiff had been restrained from issuing proceedings against a number of parties, including the first, second, fourth and fifth intended defendants without prior leave of the court. The intended plaintiff sought leave from the High Court to institute proceedings against the intended defendants. The intended plaintiff sought a declaration that ss. 1(3) and (4), 2(3), (4) and (5) of the Courts (Establishment and Constitution) Act, 1961, together with s. 33 of the Finance Act, 2001, were repugnant to the Constitution. The intended plaintiff also claimed that the division of the Supreme Court which purported to hear the appeal in Riordan v. An Taoiseach [2000] 4 I.R. 537, was operating unconstitutionally and that the appointment of a minister of state to the Government was and is illegal and was therefore unconstitutional. -

Chief Justice of Ireland

Chief Justice of Ireland The Hon. Mrs. Justice Susan Denham Chief Justice ______________________________________________ Waterford 1,100 Talks “Waterfordian John J. Hearne: A drafter of the Irish Constitution” The Large Room, Theatre Royal, Waterford Treasures Museum Waterford, 10th November 2014 2 Research assistance by Mr. Richard McNamara B.C.L., LL.M. (NUI), Solicitor Executive Legal Officer to the Chief Justice Mr. John Joseph Hearne, Senior Counsel 3 On the occasion of his call to the Inner Bar of Ireland in the Supreme Court, Four Courts, Dublin on 20th June 1939 by The Hon. Mr. Justice Timothy Sullivan, Chief Justice Introduction Good evening Ladies and Gentlemen. Thank you for the warm welcome. It is a great pleasure to be with you on this winter’s evening. I am delighted and honoured for the invitation to speak in Waterford as part of a series of Talks. The Talks commemorate 1,100 years since the founding of Ireland’s oldest city by the Vikings in 914 A.D. This is an ancient city with origins that can be traced to long before the days of the Gaelic Chieftains, the arrival of the Vikings and the Anglo-Norman conquest. In living memory Waterford was at the heart of the quest for home rule and Irish independence. Indeed, this evocative “Large Room” where we gather which was built in 1783, the same year as the first Glass factory by William and George Penrose opened, has seen many well known figures in Irish history come through its doors. The roll call includes O’Connell, Meagher, Butt, Parnell, Redmond, and King Edward VII.