Artificial Womb Technology and the Safeguarding of Children's Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phenomenological Perspectives on Technological Posthumanism

Master thesis Phenomenological perspectives on technological posthumanism Supervisors: prof. dr. Paul Ziche, dr. Iris van der Tuin Date: 10. 8. 2017 Name: Tomáš Čech Student number: 5656664 Number of Words: 24 678 i Content 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Posthumanism/transhumanism – how to make sense of it all ......................................................... 4 2.1. What is transhumanism and transhuman? ............................................................................... 7 2.2. Transhumanist perception of technology and science ........................................................... 11 2.3. Comparison between transhumanism and religion ................................................................ 13 2.4. In Summary ........................................................................................................................... 15 3. Debate about transhumanism ........................................................................................................ 15 3.1. Transhumanism as an ideology ............................................................................................. 17 3.2. Reaction to transhumanism - bioconservatism ...................................................................... 21 3.3. Bioconservative arguments – why transhumanism is not such a great idea .......................... 26 3.4. Human dignity and the transhumanism debate..................................................................... -

Columbia University Journal of Bioethics 1 2 Fall 2008

Columbia University Journal of Bioethics 1 2 Fall 2008 Columbia University Journal of Bioethics And Supplement on BIOCEP Volume VI. No 1, Fall 2008 Editorial Board Faculty Editors Editors-in-Chief Dr. John D. Loike Dr. Ruth L. Fischbach Copy Editors Soo Han Cover Design: “Entwine‖ Komal Kaothari Robyn Scheinder and Dr. John D. Loike Please send your comments to Dr. John D. Loike at: [email protected] Production & Creative Directors Robyn Scheinder Jana Bassman Web Version is available through the undergraduate page: http://www.columbia.edu/cu/ Or through http://www.bioethicscolumbia.org/ Copyright 2008 by: Columbia University Center for Bioethics NO PART OF THIS JOURNAL MAY BE COPIED OR USED WITHOUT PERMISSION. All views in the articles reflect those of the authors only. Columbia University Journal of Bioethics 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................. 5 Introductions by Dr. John Loike and Dr. Ruth Fischbach ............ …………………………………..…….6-7 Section I: Genetics The Sound and the Fury By Katie O‘Neill and Wei-Jen Hsieh……………………………………………….. Majority Report: DNA Data-banking As an Opt-Out System By Emilia Javorsky and Robyn Schneider………………………………………... Could Genetic Research Interfere with Medicine? By Jorge Jara and Joanna Etra………………………………………………. Charging You for Being You By Elisa Fung and Gabriela Vargas…………………………………………. Section II: Stem Cells and Reproductive Medicine Altered Nuclear Transfer: A Novel Way of Developing Pluripotent Stem Cells By Sarah Eberle and Tabby Khan………………………………………………... Secrets and Lies: Mandating Disclosure in Oocyte Donation By Tiffany Hsieh………………………………………………………………….. Diagnosing Disability… And Keeping It by David Yin and John Tseng……………………………………………….. Section III: Neuroethics Programmed Free Will By Elisa Fung and Lindsay Kugler…………………………………………………. -

Download Download

Volume III - Article 2 Legislating Limits on Human Embryonic Stem Cell Research Sïna A. Muscati1 Spring 2003 Copyright © 2003 University of Pittsburgh School of Law Journal of Technology Law and Policy Introduction Research on embryonic stem cells has generated great intrigue in the scientific community. Many medical researchers consider stem cell-based therapies to have the potential of treating a host of human ailments and yielding a number of medical benefits. They are motivated by the possibility of treating incurable diseases or facilitating effective treatment methods. Their enthusiasm is shared by many of those who are afflicted with these debilitating diseases. However, the methodology of this research raises numerous ethical and public policy concerns. The extraction of embryonic stem cells for research destroys the human embryo. This has generated a storm of debate about if, and in what circumstances, this research can be legally and ethically justified. The concerns are heightened further when embryos are created specifically for use in the very research that occasions their destruction. In response, numerous countries have passed legislation that attempts to control some of the more controversial aspects of embryonic stem cell research. For example, in May 2002, Canada introduced draft legislation that would govern and restrict a number of practices related to this fast-growing field of research. 1 L.L.B., third year, University of Ottawa; B.Sc. (Hons.) 2001, Carleton University. The author gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Centre of Innovation Law and Policy of the University of Toronto. The author also wishes to thank Professor Ian R. Kerr of the University of Ottawa for his guidance throughout the writing of this Article. -

Could Artificial Wombs End the Abortion Debate?

Philosophy Faculty Works Philosophy Summer 2005 Could Artificial ombsW End the Abortion Debate? Christopher Kaczor Loyola Marymount University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/phil_fac Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Christopher Kaczor, “Could Artificial ombsW End the Abortion Debate?” National Catholic Bioethics Quarterly 5.2 (Summer 2005): 73-91. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Could Artificial Wombs End the Abortion Debate? Christopher Kaczor Although artificial wombs may seem fanciful when first considered, certain trends suggest they may become reality. Between 1945 and the 1970s, the weight at which premature infants could survive dropped dramatically, moving from 1000 grams to around 400 grams.1 In 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court, in deciding Roe v. Wade, considered viability to begin around twenty-eight weeks. In 2000, premature babies were reported to have survived at eighteen weeks.2 Advanced incubators already in existence save thousands of children born prematurely each year. It is highly likely that such incubators will become even more advanced as technology progresses. Researchers are working to make super-advanced incubators, “artificial wombs,” a reality. Temple University professor Dr. Thomas Schaffer hopes to save premature infants using a synthetic amniotic fluid of oxygen-rich perfluorocarbons. Lack of funding has thus far prevented tests on human infants born prematurely, but Shaffer has successfully transferred premature lamb fetuses from their mother’s wombs and used the synthetic amniotic fluid to sustain their lives.3 At Cornell University, Dr. -

The Cybernetic Revolution and the Forthcoming Epoch of Self-Regulating Systems Grinin, Leonid; Grinin, Anton

www.ssoar.info The Cybernetic Revolution and the Forthcoming Epoch of Self-Regulating Systems Grinin, Leonid; Grinin, Anton Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / monograph Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Grinin, L., & Grinin, A. (2016). The Cybernetic Revolution and the Forthcoming Epoch of Self-Regulating Systems. Moscow: Uchitel Publishing House. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-57569-8 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Basic Digital Peer Publishing-Lizenz This document is made available under a Basic Digital Peer zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den DiPP-Lizenzen Publishing Licence. For more Information see: finden Sie hier: http://www.dipp.nrw.de/lizenzen/dppl/service/dppl/ http://www.dipp.nrw.de/lizenzen/dppl/service/dppl/ The International Center for Education and Social and Humanitarian Studies Volgograd Center for Social Research Leonid Grinin and Anton Grinin The Cybernetic Revolution and the Forthcoming Epoch of Self-Regulating Systems Moscow 2016 ББК 30г 60.5 63 Leonid Grinin and Anton Grinin The Cybernetic Revolution and the Forthcoming Epoch of Self-Regulating Systems. Moscow: Moscow branch of Uchitel Publishing House, 2016. – 216 pp. ISBN 978-5-7057-4877-8 The monograph presents the ideas about the main changes that occurred in the devel- opment of technologies from the emergence of Homo sapiens till present time and outlines the prospects of their development in the next 30–60 years and in some respect until the end of the twenty-first century. What determines the transition of a society from one level of development to another? One of the most fundamental causes is the global technological transformations. -

Abstracts: Oral Presentations *All Oral Presentations Will Take Place in the Devon Room at the Times Listed Below*

Abstracts: Oral Presentations *All oral presentations will take place in the Devon Room at the times listed below* Augustine & Culture Seminar Program (ACSP) (2:00 p.m.) Playing Mother: The Daunting Possibilities of Artificial Womb Technology Author: Hanlon, Erin Advisor: Dr. Peter Busch So often in our society, technological advances are met with the reaction that we must be wary of “playing God.” Yet, we often ignore this concern when the technology is created for the betterment of society and to solve a critical problem. This was the case for the CHOP research team that created an extra-uterine physiologic support system for the extreme premature lamb, a bio-bag system that could support an extremely premature lamb within a womb-like environment that would allow for survival and development up to a fuller point of gestation. This research, when translated to humans, would give extremely premature babies an increased chance of survival and ability to thrive post-birth with limited health complications. What I focused my research on is, what comes after this technology? We most likely will continue building upon this research until a baby could survive within this system from as early as conception. With a fully artificial womb and no need for a woman to carry a child, what possibilities does this allow for? How does this change women’s role within society? Would we even need women involved in the process? Could women donate eggs as men donate sperm and men can have a child independently? Could this possibly eliminate the abortion debate? What kind of policies will we need surrounding fetuses and the process? What potential risks does this allow for? The very real possibility of artificial womb technology brings to light many questions and ethical dilemmas that we, as a global community, may face in the very near future and we must begin to explore these possibilities in order to make the most ethical and just decisions for the future of our society. -

Unique Benefits of Ectogenesis Outweigh Potential Harms

Unique benefits of ectogenesis outweigh potential harms Citation of the final article: Kendal, Evie 2019, Unique benefits of ectogenesis outweigh potential harms, Emerging Topics in Life Sciences, vol. 3, no. 6, pp. 719-722. Published in its final form at https://doi.org/10.1042/etls20190112. This is the accepted manuscript. © 2019, The Author Reprinted with permission. Downloaded from DRO: http://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30131603 DRO Deakin Research Online, Deakin University’s Research Repository Deakin University CRICOS Provider Code: 00113B Title Unique benefits of ectogenesis outweigh potential harms. Author details Dr Evie Kendal Lecturer of Bioethics and Health Humanities Deakin University, School of Medicine Waurn Ponds, Victoria, Australia [email protected] Abstract This article will consider some of the ethical issues concerning ectogenesis technology, including possible misuse, social harms and safety risks. The article discusses three common objections to ectogenesis, namely that artificial gestation transgresses nature, risks promoting cloning and genetic engineering of offspring, and would lead to the commodification of children. Counterbalancing these concerns are an appeal to women’s rights, reproductive autonomy, and the rights of the infertile to access appropriate assisted reproductive technologies. The article concludes that the unique benefits of promoting the development of ectogenesis technology to prospective parents and children, outweigh any potential harms. Introduction Full ectogenesis refers to the artificial gestation of human embryos until independent viability, without the need for a woman’s womb at any stage.1 It represents the closing of a gap between existing artificial reproductive technologies, including in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and humidicrib incubation, to cover the entire development period. -

Spare Womb Page 1 of 6

SignOnSanDiego.com > News > Science -- Spare womb Page 1 of 6 Choose Category Sunday, Sept. 19, 2004 News Spare womb After the Fires In Iraq War on Terror Metro Reader Survey North County Please help SignOnSanDiego.com serve you better by providing the Tijuana/Border following anonymous information. This will take only a moment. California Nation Age: Gender: Male Female Mexico Country: United States Zip Code: World Business E-mail address: (*OPTIONAL) Technology Submit Ask Me Later Privacy Policy / Questions? Science Will artificial wombs mean the end of pregnancy? Health | Fitness Politics By Scott LaFee Military UNION-TRIBUNE STAFF WRITER Quicklinks Education Hotels Restaurants Travel February 25, 2004 Bars Singles Weddings Solutions Just over eight decades ago, the British Shopping Special Reports scientist J.B.S. Haldane imagined a time Baja Spas/Salons Features in which human pregnancy disappeared. Yellow Pages Weather It would be 1951, he prophesied in his Find a business... Obituaries essay "Daedalus, or Science and the Forums Future," the birth year of the first Free Newsletters Opinion ectogenic child. Columnists Weblogs Ectogenesis – a word Haldane coined – U-T Daily Paper means to be created outside the womb. U-T E-mail Edition In Haldane's trenchant vision of the future, having children would become a AP Headlines common and complete out-of-body Archives experience. E-mail Newsletters CRISTINA MARTINEZ / Union-Tribune Wireless Edition He was wrong, of course, but maybe only Noticias en Español in timing. After years of fits and starts, researchers in the United States, Enter email Internet Access Japan and elsewhere claim to have successfully tested crude prototypes of artificial wombs with animals. -

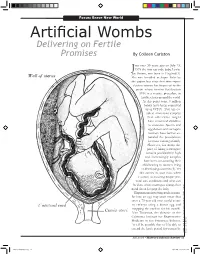

Artificial Wombs Delivering on Fertile Promises by Colleen Carlston

Focus: Brave New World Artificial Wombs Delivering on Fertile Promises By Colleen Carlston ust over 30 years ago on July 25, J1978 the first test-tube baby, Louise Joy Brown, was born in England(1). She was heralded as Super Babe by the papers but since that time repro- ductive science has improved to the point where in-vitro fertilization (IVF) is a routine procedure in fertility clinics around the world. At this point some 4 million babies have been conceived using IVF(2). This has en- abled numerous couples that otherwise might have remained childless to conceive. Sperm and egg donors and surrogate mothers have further ex- panded the possibilities for those wanting a family. However, for many the price of hiring a surrogate remains prohibitively high and increasingly couples have been out-sourcing their childbearing to women living in developing countries(3). Yet this carries its own risks when it comes to ensuring proper pre- natal care conditions and what can be done when a surrogate changes her mind about keeping the baby. Experiments involving nuclear trans- fer into an egg may soon mean that even a 75-year-old man could create an embryo using a donor egg and swapping the nucleus for his own(4). Alan Trounson, the director of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine in San Francisco, believes, “it will be possible that we’ll be able to extend the fertile period for women by credit: 20th U.S. edition of Anatomy Gray’s of the Human public domain. Body, fall 2008 • Harvard Science Review 35 ArtificialWombs.indd 35 2/9/2009 10:58:03 PM Focus: Brave New World producing germ cells from iPS [induced Pluripotent Stem-cell] technology, or by a variant of nuclear transfer, so somatic cells [which make up most of the body’s cells] become germ cells and are refreshed genetically”(1). -

Artificial Womb Technology Discourses Around Artificial Wombs the Global Perspective

Ethics of artificial wombs: missing angles and special concerns Sophya Yumakulov, BHSc, Gregor Wolbring, PhD Faculty of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, CANADA We acknowledge the support of the Wolb-Pack [email protected], [email protected] Artificial womb technology Discourses Around Artificial Wombs The Global Perspective Artificial womb technology (AWT): man- The Abortion Debate Advantages Disadvantages Keeping preterm babies alive[99] AWT would undermine women’s The Global Perspective is lacking in this made technology that can gestate a fetus. AWT can end the abortion debate – allowing women to Safer environment for the fetus[100] right to decide when/how to become literature, even though artificial womb Progress to date: Potential for fetal surgery in utero[100] mothers[3] terminate pregnancy without technology has implications on a global scale. 1986-1997 – artificial perfusion of needing to kill the fetus[3] Saving IVF embryos[4] Risks of removing a fetus from Replace surrogacy, for women unable womb[3] uteri in Italy[1] AWT will NOT end the abortion debate, because women who seek to have offspring[5] Men taking over uniquely female 1996 – Kubawara et al gestate goat abortion are trying to end not only Liberate women from negative effects function/experience[3] Global Health – AWT has the potential to increase fetus in artificial placenta for 3 pregnancy but motherhood [3] of pregnancy and birth = gender Men gaining complete control over inequities between Southern and Northern weeks[2] equality[6-8] reproduction -

5-6 State Ideation Questions 2018

Task developed by Giacomo Rotolo-Ross, University of Sydney, 2018 STATE DA VINCI DECATHLON 2018 CELEBRATING THE ACADEMIC GIFTS OF STUDENTS IN YEARS 5 & 6 IDEATION TEAM NUMBER _____________ 1 2 3 4 Total Rank /15 /15 /15 /15 /60 1 Task developed by Giacomo Rotolo-Ross, University of Sydney, 2018 IDEATION BLAST FROM THE PAST BACKGROUND One of the questions most frequently asked by young children to their parents is this: What if dinosaurs were alive today? Some answers will divert attention to the ‘still really big’ animals that inhabit our world today, whether they be on land or in oceans, while other children might simply be met with the much-maligned phrase “don’t be silly”. Rarely will parents actually discuss the ethical and practical consequences with their five-year old child, which is rather disappointing. Indeed, it took a multi-million dollar Hollywood film franchise to provide a somewhat realistic answer to this age-old question. The Jurassic Park series was, for many children and adults alike, a realisation of hours spent happily and wildly dreaming of a world where giant lizards longer than jumbo jets roamed the Earth. In this set of films, based on the book by Michael Crichton, preserved dinosaur blood and therefore DNA is found inside prehistoric gnats and ticks trapped in amber. This DNA is harnessed by a company, called InGen, in order to create a theme park inhabited by dinosaurs, all contained on an island in the North Pacific Ocean. As you might imagine, the plot soon spirals into disaster… Returning to reality, in January of 2017, palaeontologists at North Carolina State University claimed to have recovered ‘protein fragments’ from a fossilised dinosaur rib. -

Making Perfect Life: Bio-Engineering (In) the 21St Century Is the Result of the Second Phase of the STOA-Project “Making Perfect Life”

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT Science and Technology Options Assessment S T O A MAKING PERFECT LIFE BIO-ENGINEERING (IN) THE 21st CENTURY MONITORING REPORT PHASE II (IP/A/STOA/FWC-2008-96/LOT6/SC1) PE 471.570 DIRECTORATE GENERAL FOR INTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT E: LEGISLATIVE COORDINATION AND CONCILIATIONS SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY OPTIONS ASSESSMENT MAKING PERFECT LIFE BIO-ENGINEERING (IN) THE 21st CENTURY MONITORING REPORT - PHASE II Abstract The report describes four fields of bio-engineering: engineering of living artefacts (chapter 2), engineering of the body (chapter 3), engineering of the brain (chapter 4), and engineering of intelligent artefacts (chapter 5). Each chapter describes the state of the art of these bio-engineering fields, and whether the concepts “biology becoming technology” and “technology becoming biology” are helpful in describing and understanding, from an engineering perspective, what is going on in each R&D terrain. Next, every chapter analyses to what extent the various research strands within each field of bio-engineering are stimulated by the European Commission, i.e., are part and parcel of the European Framework program. Finally, each chapter provides an overview of the social, ethical and legal questions that are raised by the various scientific and technological activities involved. The report’s final chapter discusses to what extent the trends “biology becoming technology” and vice versa capture many of the developments that are going on in the four bio-engineering fields we have mapped. The report also reflects on the social, ethical and legal issues that are raised by the two bio- engineering megatrends that constitute a new technology wave.