New Frontiers in Micro-Savings – March 2008 I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8364 Licensed Charities As of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T

8364 Licensed Charities as of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T. Rowe Price Program for Charitable Giving, Inc. The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust USA, Inc. 100 E. Pratt St 25283 Cabot Road, Ste. 101 Baltimore MD 21202 Laguna Hills CA 92653 Phone: (410)345-3457 Phone: (949)305-3785 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 MICS 52752 MICS 60851 1 For 2 Education Foundation 1 Michigan for the Global Majority 4337 E. Grand River, Ste. 198 1920 Scotten St. Howell MI 48843 Detroit MI 48209 Phone: (425)299-4484 Phone: (313)338-9397 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 46501 MICS 60769 1 Voice Can Help 10 Thousand Windows, Inc. 3290 Palm Aire Drive 348 N Canyons Pkwy Rochester Hills MI 48309 Livermore CA 94551 Phone: (248)703-3088 Phone: (571)263-2035 Expiration Date: 07/31/2021 Expiration Date: 03/31/2020 MICS 56240 MICS 10978 10/40 Connections, Inc. 100 Black Men of Greater Detroit, Inc 2120 Northgate Park Lane Suite 400 Attn: Donald Ferguson Chattanooga TN 37415 1432 Oakmont Ct. Phone: (423)468-4871 Lake Orion MI 48362 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Phone: (313)874-4811 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 25388 MICS 43928 100 Club of Saginaw County 100 Women Strong, Inc. 5195 Hampton Place 2807 S. State Street Saginaw MI 48604 Saint Joseph MI 49085 Phone: (989)790-3900 Phone: (888)982-1400 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 58897 MICS 60079 1888 Message Study Committee, Inc. -

Agricultural Value Added Services (Agri VAS): Market Entry Toolkit Authors: Amol Jadhav, Natalia Pshenichnaya and Fiona Smith, GSMA Magri Programme

Agricultural Value Added Services (Agri VAS): Market Entry Toolkit Authors: Amol Jadhav, Natalia Pshenichnaya and Fiona Smith, GSMA mAgri Programme. Contents 3—4 Introduction 5—9 Chapter 1 Market Opportunity 10—16 Chapter 2 Market Assessment and User Needs 17—21 Chapter 3 Marketing 22—30 Chapter 4 Service Design 31—38 Chapter 5 Commercial Model and Business Case for Agri VAS 39 Glossary GSMA — mAgri Programme 3 Market Entry Toolkit - Agri VAS Introduction The furious growth of mobile in developing countries, and rural regions in particular, presents a landmark opportunity to deliver critical, information-based agricultural services to rural poor smallholder farmers. There are over 2.3 billion people living in poverty and the majority earn their primary livelihood from small farms in developing countries. The yields of these farmers, especially those in sub-Saharan Africa, typically represent a fifth of those in the developed world. There is a raft of reasons for this, one of which is a lack of access to relevant and actionable agricultural information. Yet this problem is eminently superable. The right information, absorbed and applied correctly, can double or triple productivity in many of these households. Mobile is the leapfrog technology that allows us to complement existing extension efforts by stepping up and meeting this information need. About the Authors This document was written by members of the GSMA mAgri Programme. The GSM Association represents the interests of mobile operators worldwide and within this, the GSMA Development Fund works to identify opportunities in emerging markets for social, economic and environmental impact through mobile services. -

Press Release the Crédit Agricole Grameen Foundation and Crédit Agricole CIB Pool Their Expertise to Support Microfinance In

4 September 2019 Press Release The Crédit Agricole Grameen Foundation and Crédit Agricole CIB pool their expertise to support microfinance in India The Crédit Agricole Grameen Foundation and Crédit Agricole Corporate and Investment Bank (Crédit Agricole CIB) are teaming up to aid and fund Indian microfinance institutions supporting the business plans of populations excluded from the traditional banking system. Through this partnership, Crédit Agricole Group is putting its expertise to work for inclusive finance in India, and has earmarked funding of €12 million to that end. Crédit Agricole CIB will be granting loans of up to €12 million total in euro-equivalent local currencies to Indian microfinance institutions, under the guarantee and oversight of the Crédit Agricole Grameen Foundation. The Foundation will be responsible for originating, examining and monitoring funding applications. The loans granted to Indian microfinance institutions will be used to promote access to financial services for as many as possible, in a bid to encourage the development of revenue-generating businesses. Rural populations and female entrepreneurs will be the primary beneficiaries. This partnership underscores Credit Agricole CIB’s commitment to supporting inclusive finance in India. “The complementarity of our expertise played an optimal role in this partnership, with the Foundation contributing its keen understanding of microfinance issues and the Credit Agricole CIB Indian branches their tried and tested knowledge of complex and ever-changing local banking regulations,” explained Emmanuel Bouvier d’Yvoire, Senior Country Officer of Crédit Agricole CIB for India. Operating in India since 1981, Crédit Agricole CIB is established in Bangalore, Chennai, Delhi, Mumbai and Pune. -

Solution for the Poorest: Insights from Savings Behavior of Clients

Acknowledgements This study would not have been possible without the financial support of the Rockefeller Foundation. We would also like to acknowledge Intellecap as a knowledge partner in the development of this case study. Grameen Foundation, a global nonprofit organization, helps the world’s poorest people – especially women – lift themselves out of poverty by providing appropriate financial services, life-changing information and unique business opportunities. Found in 1997, Grameen Foundation has offices in Washington, D.C.; Seattle, WA; Colombia, Ghana, Hong Kong; Indonesia; Kenya; the Philippines; and Uganda. Microfinance pioneer Dr. Muhammad Yunus, founder of Grameen Bank and winner of the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize, is a founding member of its Board of Directors, and now serves as director emeritus. For more information, please visit grameenfoundation.org. Grameen Foundation India is a social business and a wholly owned subsidiary of Grameen Foundation that catalyses double bottom line approaches to serving the poor and the poorest. Its mission is to enable the poor, especially the poorest, to move out of poverty by strengthening institutions and businesses that serve them. Grameen Foundation India aims to achieve this by enabling the growth of truly double bottom line entities that use quantitative and verifiable measures of social results and by demonstrating new business models for serving the poorest. It currently focuses on enabling the provision of financial services and information services. You can learn more at http://grameenfoundation.in/ ©2013 Grameen Foundation USA. All rights reserved. Except for use in a review, the reproduction or utilization of this work or part of it in any form or by electronics, or other means not known or hereafter invented, including xerography, photocopying, recording, and in any information storage, transmission or retrieval system, including CD ROM, online or via the Internet, is forbidden without the written permission of Grameen Foundation. -

The Growth Guarantees Program a Promise

The GrowTh GuaranTees proGram a promise delivered Grameen Foundation In 1974, Professor Muhammad Yunus began making tiny loans to the Bangladeshi rural poor. He discovered that what we now call “micro-loans” were a remarkably effective way to make a significant difference in the lives of poor families. Now, microfinance has become one of the most productive and sustainable ways to fight global poverty on a large scale. Microfinance empowers the world’s poorest people to start their journeys from poverty. Often called “bankers to the poor,” microfinance institutions (MFIs) currently serve about 150 million poor families worldwide. With loans as little as $100, a poor woman can start a small, income-producing business that allows her to improve the life and livelihood of her family, breaking the generational cycle of poverty. Inspired by the microfinance concept pioneered by Grameen Bank, Grameen Foundation was created in 1997 to grow the microfinance sector. Our goal is simple – we want to see poor people, especially the poorest and those living in harder to reach areas, have access to microfinance and technology and as a result of access to these services, move themselves out of poverty. We envision a world where the poor have broken the generational chain of poverty and lead lives of respect, dignity, and opportunity. © Grameen Foundation uSa, 2010 The Growth Guarantees program “a promise delivered” The Growth Guarantees (GG) program was developed over one weekend at the legendary venture capitalist John Doerr’s house. The program managed to attract virtually all of the $31 million Round 1 capability from people attending that weekend event. -

Participant List

Participant List 10/20/2019 8:45:44 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Ramil Abbasov Chariman of the Managing Spektr Socio-Economic Azerbaijan Board Researches and Development Public Union Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Amr Abdallah Director, Gulf Programs Educaiton for Employment - United States EFE HAGAR ABDELRAHM African affairs & SDGs Unit Maat for Peace, Development Egypt AN Manager and Human Rights Abukar Abdi CEO Juba Foundation Kenya Nabil Abdo MENA Senior Policy Oxfam International Lebanon Advisor Mala Abdulaziz Executive director Swift Relief Foundation Nigeria Maryati Abdullah Director/National Publish What You Pay Indonesia Coordinator Indonesia Yussuf Abdullahi Regional Team Lead Pact Kenya Abdulahi Abdulraheem Executive Director Initiative for Sound Education Nigeria Relationship & Health Muttaqa Abdulra'uf Research Fellow International Trade Union Nigeria Confederation (ITUC) Kehinde Abdulsalam Interfaith Minister Strength in Diversity Nigeria Development Centre, Nigeria Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Shahlo Abdunabizoda Director Jahon Tajikistan Shontaye Abegaz Executive Director International Insitute for Human United States Security Subhashini Abeysinghe Research Director Verite -

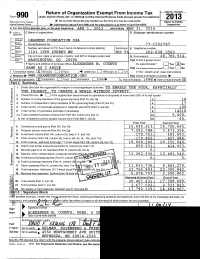

GRAMEEN FOUNDATION USA Lchange Doing Business As 73-1502797 Ejretuan Number and Street (Or P 0

Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax OMB No 1545-0047 Form section 501(c 990 Under ), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung 2012 benefit trust or private foundation ) Department or the Treasury Open to Public organization may Internal Revenue Service ► The have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements Inspection A For the 2012 calendar year , or tax year beginning APR 1 2012 and ending MAR 31 2013 B Check if C Name of organization D Employer identification number applicable •- Echange GRAMEEN FOUNDATION USA Lchange Doing Business As 73-1502797 Ejretuan Number and street (or P 0. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number Elaeed'n 1101 15TH STREET NW 3RD F 202-628-3560 Amended return City, town, or post office, state, and ZIP code G Gross receipts $ 21 , 423 , 392 Applica- WASHINGTON , DC 2 0 0 0 5 H(a) Is this a group return pending F Name and address of principal officer ALEXANDER M. COUNTS for affiliates' 0 Yes ® No SAME AS ABOVE H(b) Are all affiliates Included =Yes = No I Tax-exempt status ® 501 ( c )( 3 ) 0 501 c 1 ( insert no. ) 4947 (a )( 1 ) or 0 527 If "No," attach a list (see instructions) Website WWW. GRAMEENFOUNDATION. J : 00, ORG H(c) Grou p exem ption number ► K Form of or anization: ® Corporation 0 Trust El Association El Other ► L Year of formation: 19 9 6 1 M State of le al domicile: 01 Part I Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission or most significant activities TO ENABLE THE POOR, ESPECIALLY THE POOREST, TO CREATE A WORLD WITHOUT POVERTY. -

Breaking the Cycle GRAMEEN FOUNDATION OVERVIEW

ANNUAL REPORT 2013-2014 Breaking the Cycle GRAMEEN FOUNDATION OVERVIEW Grameen Foundation helps the world’s poor reach their potential. We provide access to essential financial services and to information on agriculture and health that addresses the specific needs of poor households and communities. We also develop tools to improve the effectiveness of our fellow poverty-focused organizations. Grameen Foundation was started in 1997 to harness the underappreciated strengths of the poor, an approach inspired by Nobel Laureate Professor Muhammad Yunus and the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh. Professor Yunus was a founding member of our Board of Directors and today serves as director emeritus. Our high standards and efficiency have earned us a four-star rating from Charity Navigator and recognition from the Better Business Bureau’s Wise Giving Alliance and Guidestar’s Exchange Seal. GRAMEEN FOUNDATION 2013–2014 ANNUAL REPORT Letter from the President and Chairman of the Board 3 Our Story 4 Financial Highlights 12 Board of Directors 15 Staff 16 Bankers without Borders® Volunteers 17 Take Action 18 WWW.GRAMEENFOUNDATION.ORG 1 2 WWW.GRAMEENFOUNDATION.ORG LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT AND CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD We all had good reason for cheer this past year. New World Bank figures showed that the number of people living on less than $1.25 per day—the international standard for living in extreme poverty—fell by almost 60 percent during the past three decades. Life expectancy has increased—even in the poorest countries—and fewer people are dying from preventable diseases. Though there’s still a lot of work to be done, it is important for us to celebrate these victories in the battle to defeat global poverty. -

“A POVERTY LENS on FINANCIAL INCLUSION” Based on a Representative State-Wide Study of Microfinance in Karnataka

MICROFINANCE “A POVERTY LENS ON FINANCIAL INCLUSION” Based on A Representative State-wide Study of Microfinance in Karnataka Executive Summary................................................................................01 A “Burden of Proof”...............................................................................11 A Kaleidoscope to See Through.............................................................12 Unfolding Microfinance by Measuring Outreach to The Poor In Karnataka ...........................................................................15 Linking to Debates of the Day ..............................................................27 What Next? ............................................................................................33 Looking Beyond Livelihoods: Microfinance Not Only For Enterprise Needs.............................................................................34 Annexures ..............................................................................................37 CONTRIBUTIONS AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We acknowledge that the microfinance practitioners in Karnataka have had the foresight to look at poverty measurement as an important factor. More importantly, their willingness to work together has been more than commendable. To the credit of all the stakeholders we worked with, and in particular, the participating MFIs, we are indeed grateful for engaging in very forthright discussions with us throughout the year long effort behind the study. Names of Participating MFIs 1. Chaitanya 2. Grameen -

Channel Innovation for Financial Inclusion with a Long Term Perspective, As It Is a Time- and Effort- Intensive Process

Channel Innovation for Financial Inclusion A Case Study to understand how Cashpor transformed from a MFI to a MFI-BC to provide multiple financial services to the poor October 2013 A Grameen Foundation India Series 1 Acknowledgements This study would not have been possible without the support of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. We would also like to thank Cashpor, ICICI Bank and Eko India for their support to the project and the case study. Lastly, we would like to acknowledge Intellecap as a knowledge partner in the development of this case study. Grameen Foundation, a global nonprofit organization, helps the world’s poorest people – especially women – lift themselves out of poverty by providing appropriate financial services, life-changing information and unique business opportunities. Founded in 1997, Grameen Foundation has offices in Washington, D.C.; Seattle, Washington; Colombia; Ghana; Hong Kong; Indonesia; Kenya; the Philippines; and Uganda. Microfinance pioneer Dr. Muhammad Yunus, founder of Grameen Bank and winner of the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize, is a founding member of its Board of Directors, and now serves as director emeritus. For more information, please visit grameenfoundation.org. Grameen Foundation India is a social business and a wholly owned subsidiary of Grameen Foundation that catalyses double bottom line approaches to serving the poor and the poorest. Its mission is to enable the poor, especially the poorest, to move out of poverty by strengthening institutions and businesses that serve them. Grameen Foundation India aims to achieve this by enabling the growth of truly double bottom line entities that use quantitative and verifiable measures of social results and by demonstrating new business models for serving the poorest. -

Grameen Foundation

Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax OMB No 1545-0047 Form ^^0 Under section 501 (c), 527, or 4947( a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except private foundations) 2013 Do not enter Social Security numbers department of the Treasury ► on this form as it may be made public Open to Public Internal Revenue Service Information about Form 990 and its instructions is at www irs. gov/form990. Inspection A For the 2013 calendar year , or tax year beginning APR 1 , 2013 and ending MAR 31 2014 B Check if C Name of organization D Employer identification number applicable -Ichanges GRAMEEN FOUNDATION USA ^ Nhange Doin g Business As 7 3 -1502797 ^reituan Number and street ( or P.O box if mail is not delivered to street address ) Room/suite E Telephone number E:Iatedb" 1101 15TH STREET NW 3RD F 202 - 628-3560 Amended return City or town, state or province , country , and ZIP or foreign postal code G Gross receipts $ 20 , 786 , 914. Iica- DAgten WASHINGTON , DC 2 0 0 0 5 H(a) Is this a group return pending F Name and address of principal officer ALEXANDER M. COUNTS for subordinates? Yes ®No SAME AS C ABOVE H(b) Are all subordi nates included'?DYes 0 No Tax-exem pt status ® 501 c 3 [:1501 ( c )( 1 ( insert no. ) 0 4947 ( a )( 1 ) or 0 527 If " No," attach a list (see instructions) J Website : 00, WWW. GRAMEENFOUNDAT ION . ORG H (c) Grou p exemption number ► K Form of organization . n Corporation F--1 Trust F-1 Association F-1 Other ► L Year of formation- 19 9 6 M State of lenal domicile, OR Part I I Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission or most significant activities TO ENABLE THE POOR, ESPECIALLY C THE POOREST, TO CREATE A WORLD WITHOUT POVERTY. -

Annual Report 2020 “We Have Received Improved Seeds, Which I Have Grown on a Half-Acre

Annual Report 2020 “We have received improved seeds, which I have grown on a half-acre. The yields are very high, and this makes me very happy. I will grow these seeds again.” Grameen Farm Development Plan beneficiary, Brong-Ahafo, Ghana Table of Contents Message from President and Chair of Board: Detours do not change our destination. 4 The Grameen Model: Amplifying the power of the poor. 7 Where We Work. 9 Responding to a Crisis: COVID-19 RELIEF program targets 3,500 vulnerable female micro-entrepreneurs. 11 Emergency Cash for most vulnerable women. 12 From Ebola to COVID-19: Arming frontline workers with truth. 15 Grameen by the Numbers. 18 Financial Inclusion: As Agent Network grows, Mittras become ‘essential.’ 20 WomenLink II catalyzes economic empowerment. 21 Digital Farming: Programs pivot to ensure farmers don’t lose ground. 23 Refugee Finance Solutions: Helping families rebuild lives in Uganda. 26 Digital Literacy Training Guide helps refugees access financial services. 27 WAGE: Reducing barriers to women’s empowerment. 28 Strengthening Ecosystems. 30 A Look Ahead: Focus on India. 31 Our Partners: They light our way. 32 Consolidated Statement of Activities. 33 Grameen Foundation Leadership. 35 Bankers without Borders: A shout out to skillanthropists. 36 To Our Supporters: With your help, we can do more. 37 About Grameen. 38 Grameen Foundation Annual Report 2020 3 CEO and Board Chair Letter Detours do not change our destination. Last year, our Annual Report letter concluded with: “We enter FY 2020 more inspired than ever and confident that we have created a roadmap to achieve limitless milestones ahead.” Never could we have foreseen the detour that was 2020.