Microtraining and the Sierra Leone Police: an Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Cascade Training

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Security Council Distr.: General 10 December 2004

United Nations S/2004/965 Security Council Distr.: General 10 December 2004 Original: English Twenty-fourth report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone I. Introduction 1. By its resolution 1562 (2004) of 17 September 2004, the Security Council extended the mandate of the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone (UNAMSIL) until 30 June 2005. By the same resolution, the Council requested me to report regularly on progress made in peace consolidation in Sierra Leone. The present report is submitted pursuant to that request, and provides an assessment of the security situation and the overall progress made in the drawdown of the Mission since my last report, of 9 September 2004 (S/2004/724). It also describes the preparations for the transition from the current configuration of UNAMSIL to its residual presence in Sierra Leone, as set out in resolution 1537 (2004) of 30 March 2004. II. Security situation 2. During the reporting period, the overall security situation in Sierra Leone has remained generally calm and stable. It was therefore possible for UNAMSIL, on 23 September 2004, to transfer to the Government of Sierra Leone primary responsibility for security in the Western Area, including Freetown, which was the last area under UNAMSIL control, thereby completing the overall transfer. Consequently, the Mission’s tasks are being readjusted, in consultation with the Government, to a role of providing support to the national security services. 3. Since the commencement of trials by the Special Court on 3 June 2004, there have been no significant threats reported against the Court. -

G U I N E a Liberia Sierra Leone

The boundaries and names shown and the designations Mamou used on this map do not imply official endorsement or er acceptance by the United Nations. Nig K o L le n o G UINEA t l e a SIERRA Kindia LEONEFaranah Médina Dula Falaba Tabili ba o s a g Dubréka K n ie c o r M Musaia Gberia a c S Fotombu Coyah Bafodia t a e r G Kabala Banian Konta Fandié Kamakwie Koinadugu Bendugu Forécariah li Kukuna Kamalu Fadugu Se Bagbe r Madina e Bambaya g Jct. i ies NORTHERN N arc Sc Kurubonla e Karina tl it Mateboi Alikalia L Yombiro Kambia M Pendembu Bumbuna Batkanu a Bendugu b Rokupr o l e Binkolo M Mange Gbinti e Kortimaw Is. Kayima l Mambolo Makeni i Bendou Bodou Port Loko Magburaka Tefeya Yomadu Lunsar Koidu-Sefadu li Masingbi Koundou e a Lungi Pepel S n Int'l Airport or a Matotoka Yengema R el p ok m Freetown a Njaiama Ferry Masiaka Mile 91 P Njaiama- Wellington a Yele Sewafe Tongo Gandorhun o Hastings Yonibana Tungie M Koindu WESTERN Songo Bradford EAS T E R N AREA Waterloo Mongeri York Rotifunk Falla Bomi Kailahun Buedu a i Panguma Moyamba a Taiama Manowa Giehun Bauya T Boajibu Njala Dambara Pendembu Yawri Bendu Banana Is. Bay Mano Lago Bo Segbwema Daru Shenge Sembehun SOUTHE R N Gerihun Plantain Is. Sieromco Mokanje Kenema Tikonko Bumpe a Blama Gbangbatok Sew Tokpombu ro Kpetewoma o Sh Koribundu M erb Nitti ro River a o i Turtle Is. o M h Sumbuya a Sherbro I. -

Sierra Leone Unamsil

13o 30' 13o 00' 12o 30' 12o 00' 11o 30' 11o 00' 10o 30' Mamou The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply ger GUINEA official endorsemenNt ior acceptance by the UNAMSIL K L United Nations. o l o e l n a Deployment as of t e AugustKindia 2005 Faranah o o 10 00' Médina 10 00' National capital Dula Provincial capital Tabili s a Falaba ie ab o c K g Dubréka Town, village r n a o c M S Musaia International boundary t Gberia Coyah a Bafodia UNMO TS-11 e Provincial boundary r Fotombu G Kabala Banian Konta Bendugu 9o 30' Fandié Kamakwie Koinadugu 9o 30' Forécariah Kamalu li Kukuna Fadugu Se s ie agbe c B Madina r r a e c SIERRA LEONE g Jct. e S i tl N Bambaya Lit Ribia Karina Alikalia Kurubonla Mateboi HQ UNAMSIL Kambia M Pendembu Yombiro ab Batkanuo Bendugu l e Bumbuna o UNMO TS-1 o UNMO9 00' HQ Rokupr a 9 00' UNMO TS-4 n Mamuka a NIGERIA 19 Gbinti p Binkolo m Kayima KortimawNIGERIA Is. 19 Mange a Mambolo Makeni P RUSSIA Port Baibunda Loko JORDAN Magburaka Bendou Mape Lungi Tefeya UNMO TS-2 Bodou Lol Rogberi Yomadu UNMO TS-5 Lunsar Matotoka Rokel Bridge Masingbi Koundou Lungi Koidu-Sefadu Pepel Yengema li Njaiama- e Freetown M o 8o 30' Masiaka Sewafe Njaiama 8 30' Goderich Wellington a Yonibana Mile 91 Tungie o Magbuntuso Makite Yele Gandorhun M Koindu Hastings Songo Buedu WESTERN Waterloo Mongeri Falla York Bradford UNMO TS-9 AREA Tongo Giehun Kailahun Tolobo ia Boajibu Rotifunk a T GHANA 11 Taiama Panguma Manowa Banana Is. -

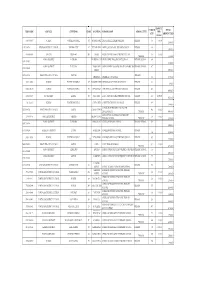

Summary of Recovery Requirements (Us$)

National Recovery Strategy Sierra Leone 2002 - 2003 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 4. RESTORATION OF THE ECONOMY 48 INFORMATION SHEET 7 MAPS 8 Agriculture and Food-Security 49 Mining 53 INTRODUCTION 9 Infrastructure 54 Monitoring and Coordination 10 Micro-Finance 57 I. RECOVERY POLICY III. DISTRICT INFORMATION 1. COMPONENTS OF RECOVERY 12 EASTERN REGION 60 Government 12 1. Kailahun 60 Civil Society 12 2. Kenema 63 Economy & Infrastructure 13 3. Kono 66 2. CROSS CUTTING ISSUES 14 NORTHERN REGION 69 HIV/AIDS and Preventive Health 14 4. Bombali 69 Youth 14 5. Kambia 72 Gender 15 6. Koinadugu 75 Environment 16 7. Port Loko 78 8. Tonkolili 81 II. PRIORITY AREAS OF SOUTHERN REGION 84 INTERVENTION 9. Bo 84 10. Bonthe 87 11. Moyamba 90 1. CONSOLIDATION OF STATE AUTHORITY 18 12. Pujehun 93 District Administration 18 District/Local Councils 19 WESTERN AREA 96 Sierra Leone Police 20 Courts 21 Prisons 22 IV. FINANCIAL REQUIREMENTS Native Administration 23 2. REBUILDING COMMUNITIES 25 SUMMARY OF RECOVERY REQUIREMENTS Resettlement of IDPs & Refugees 26 CONSOLIDATION OF STATE AUTHORITY Reintegration of Ex-Combatants 38 REBUILDING COMMUNITIES Health 31 Water and Sanitation 34 PEACE-BUILDING AND HUMAN RIGHTS Education 36 RESTORATION OF THE ECONOMY Child Protection & Social Services 40 Shelter 43 V. ANNEXES 3. PEACE-BUILDING AND HUMAN RIGHTS 46 GLOSSARY NATIONAL RECOVERY STRATEGY - 3 - EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ▪ Deployment of remaining district officials, EXECUTIVE SUMMARY including representatives of line ministries to all With Sierra Leone’s destructive eleven-year conflict districts (by March). formally declared over in January 2002, the country is ▪ Elections of District Councils completed and at last beginning the task of reconstruction, elected District Councils established (by June). -

From Emergency Evacuation to Community Empowerment Review

UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR REFUGEES EVALUATION AND POLICY ANALYSIS UNIT From emergency evacuation to community empowerment Review of the repatriation and reintegration programme in Sierra Leone By Stefan Sperl and EPAU/2005/01 Machtelt De Vriese February 2005 Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit UNHCR’s Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit (EPAU) is committed to the systematic examination and assessment of UNHCR policies, programmes, projects and practices. EPAU also promotes rigorous research on issues related to the work of UNHCR and encourages an active exchange of ideas and information between humanitarian practitioners, policymakers and the research community. All of these activities are undertaken with the purpose of strengthening UNHCR’s operational effectiveness, thereby enhancing the organization’s capacity to fulfil its mandate on behalf of refugees and other displaced people. The work of the unit is guided by the principles of transparency, independence, consultation, relevance and integrity. Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Case Postale 2500 1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland Tel: (41 22) 739 8249 Fax: (41 22) 739 7344 e-mail: [email protected] internet: www.unhcr.org/epau All EPAU evaluation reports are placed in the public domain. Electronic versions are posted on the UNHCR website and hard copies can be obtained by contacting EPAU. They may be quoted, cited and copied, provided that the source is acknowledged. The views expressed in EPAU publications are not necessarily those of UNHCR. The designations and maps used do not imply the expression of any opinion or recognition on the part of UNHCR concerning the legal status of a territory or of its authorities. -

Emis Code Council Chiefdom Ward Location School Name

AMOUNT ENROLM TOTAL EMIS CODE COUNCIL CHIEFDOM WARD LOCATION SCHOOL NAME SCHOOL LEVEL PER ENT AMOUNT PAID CHILD 5103-2-09037 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 391 ROGBANGBA ABDUL JALIL ACADEMY PRIMARY PRIMARY 369 10,000 3,690,000 1291-2-00714 KENEMA DISTRICT COUNCIL KENEMA CITY 67 FULAWAHUN ABDUL JALIL ISLAMIC PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 380 3,800,000 4114-2-06856 BO CITY TIKONKO 289 SAMIE ABDUL TAWAB HAIKAL PRIMARY SCHOOL 610 10,000 PRIMARY 6,100,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO DOWN BALLOP ABDULAI IBN ABASS PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY SCHOOL 694 1391-2-02007 6,940,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO TAMBA ABU ABDULAI IBNU MASSOUD ANSARUL ISLAMIC MISPRIMARY SCHOOL 407 1391-2-02009 STREET 4,070,000 5208-2-10866 FREETOWN CITY COUNCIL WEST III PRIMARY ABERDEEN ABERDEEN MUNICIPAL 366 3,660,000 5103-2-09002 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 397 KOSSOH TOWN ABIDING GRACE PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 62 620,000 5103-2-08963 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 373 BENGUEMA ABNAWEE ISLAMIC PRIMARY SCHOOOL PRIMARY 405 4,050,000 4109-2-06695 BO DISTRICT KAKUA 303 KPETEMA ACEF / MOUNT HORED PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 411 10,000.00 4,110,000 Not found WARDC WATERLOO RURAL COLE TOWN ACHIEVERS PRIMARY TUTORAGE PRIMARY 388 3,880,000 ACTION FOR CHILDREN AND YOUTH 5205-2-09766 FREETOWN CITY COUNCIL EAST III CALABA TOWN 460 10,000 DEVELOPMENT PRIMARY 4,600,000 ADA GORVIE MEMORIAL PREPARATORY 320401214 BONTHE DISTRICT IMPERRI MORIBA TOWN 320 10,000 PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 3,200,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO BONGALOW ADULLAM PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY SCHOOL 323 1391-2-01954 3,230,000 1109-2-00266 KAILAHUN DISTRICT LUAWA KAILAHUN ADULLAM PRIMARY -

The Chiefdoms of Sierra Leone

The Chiefdoms of Sierra Leone Tristan Reed1 James A. Robinson2 July 15, 2013 1Harvard University, Department of Economics, Littauer Center, 1805 Cambridge Street, Cambridge MA 02138; E-mail: [email protected]. 2Harvard University, Department of Government, IQSS, 1737 Cambridge Street., N309, Cambridge MA 02138; E-mail: [email protected]. Abstract1 In this manuscript, a companion to Acemoglu, Reed and Robinson (2013), we provide a detailed history of Paramount Chieftaincies of Sierra Leone. British colonialism transformed society in the country in 1896 by empowering a set of Paramount Chiefs as the sole authority of local government in the newly created Sierra Leone Protectorate. Only individuals from the designated \ruling families" of a chieftaincy are eligible to become Paramount Chiefs. In 2011, we conducted a survey in of \encyclopedias" (the name given in Sierra Leone to elders who preserve the oral history of the chieftaincy) and the elders in all of the ruling families of all 149 chieftaincies. Contemporary chiefs are current up to May 2011. We used the survey to re- construct the history of the chieftaincy, and each family for as far back as our informants could recall. We then used archives of the Sierra Leone National Archive at Fourah Bay College, as well as Provincial Secretary archives in Kenema, the National Archives in London and available secondary sources to cross-check the results of our survey whenever possible. We are the first to our knowledge to have constructed a comprehensive history of the chieftaincy in Sierra Leone. 1Oral history surveys were conducted by Mohammed C. Bah, Alimamy Bangura, Alieu K. -

Supporting Governance Transformation in Sierra Leone Through Devolution and Strengthening Local Governance

Supporting Governance Transformation in Sierra Leone Through Devolution and Strengthening Local Governance Sierra Leone is endowed with rich natural resources but is one of the poorest countries in the world. An eleven-year war during 1991-2002 destroyed the country’s infrastructure and social fabric. Centralization of political power and public resources in the capital city Freetown and marginalization of the provinces was seen as one of the root causes of the war. Since the end of the war, the country has embarked on a resettlement, reintegration, reconstruction and recovery program. Although public spending on education, health, agriculture and infrastructure is significant, centralized and non-transparent management of the resource reduced its impact on service delivery and poverty. Currently Sierra Leone ranked the lowest in the United Nation Human Development Indicators, and seventy percent of the population is under poverty. Comprehensive governance diagnoses revealed other areas of governance failures, including a weak judiciary subject to political interference; a de-motivated and under- skilled bureaucracy and rampant rent-seeking behavior; a weak legislature unable to provide effective oversight of the executive. The civil society and the private sector are not sufficiently independent of the state and are not effectively organized to keep it accountable. Reform efforts spread across many fronts with varying degrees of political commitment and design and implementation capacity. How does IDA select the most promising entry points of governance transformation? IDA support to GoSL during the war and immediately after the war focused mainly on strengthen and sustaining the government machinery, notably its core economic management capacity in the Ministry of Finance, National Revenue Authority, Statistics Sierra Leone. -

Sierra Leone Recovery Strategy for Newly Accessible Areas

Sierra Leone Recovery Strategy for Newly Accessible Areas National Recovery Committee May 2002 Table of Contents GLOSSARY OF ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................ 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 6 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 12 1.1. The National Recovery Structure........................................................................... 12 1.2. A bottom-up approach emphasising local consultations ....................................... 12 1.3. A recovery strategy to promote stability................................................................ 13 2. RESTORATION OF CIVIL AUTHORITY................................................................. 14 2.1. District Administration .......................................................................................... 15 2.2. District Councils .................................................................................................... 16 2.3. Sierra Leone Police................................................................................................ 17 2.4. Courts..................................................................................................................... 19 2.5. Prisons.................................................................................................................... 20 2.6. Paramount Chiefs and Chiefdom -

Security Council Distr.: General 20 September 2005

United Nations S/2005/596 Security Council Distr.: General 20 September 2005 Original: English Twenty-sixth report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone I. Introduction 1. By its resolution 1610 (2005) of 30 June 2005, the Security Council extended the mandate of the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone (UNAMSIL) for a final period of six months, until 31 December 2005. In that resolution, the Council welcomed my intention to keep the security, political, humanitarian and human rights situation in Sierra Leone under close review and to report regularly to it. The present report is submitted pursuant to that request and provides an assessment of the security situation and the overall progress made in the drawdown of the Mission since my last report, of 26 April (S/2005/273) and the addendum to it of 28 July (S/2005/273/Add.2). II. Security situation 2. The overall security situation in Sierra Leone has remained generally calm and stable during the period under review. Furthermore, the Government of Sierra Leone has taken further steps towards assuming full responsibility for the maintenance of security, thus further contributing to the consolidation of peace in the country. 3. Despite funding shortfalls, the performance of the Office of National Security has continued to improve, as has, in particular, its coordination capacity. The national security structure has been consolidated country-wide by means of the provincial and district security committees, which bring together key local officials, including local councils, commanders of the Sierra Leone police and the Republic of Sierra Leone Armed Forces. -

Sierra Leone Unipsil

13o 30' 13o 00' 12o 30' 12o 00' 11o 30' 11o 00' 10o 30' Mamou The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply ger GUINEA official endorsemenNt ior acceptance by the UNIPSIL K L United Nations. o l o e l Deployment as of n a t e SeptemberKindia 2008 Faranah o o 10 00' Médina 10 00' National capital Dula Provincial capital Tabili s a Falaba ie ab o c K g Dubréka Town, village r n a o c M S Musaia International boundary t Gberia Coyah a Bafodia e Provincial boundary r Fotombu G Kabala Banian Konta Bendugu 9o 30' Fandié Kamakwie NORTHERN Koinadugu 9o 30' Forécariah Kamalu li Kukuna Fadugu Se s ie c Madina r r a Bagbe e c g Jct. e S i tl N Bambaya Lit Ribia Karina Alikalia Kurubonla Mateboi Kambia M Pendembu Yombiro ab Batkanuo Bendugu l e Bumbuna o o 9 00' Rokupr a 9 00' n Mamuka a Mange Gbinti p Binkolo m Kayima Mambolo a Port Baibunda Makeni P HQ UNIPSIL Loko Bendou Lungi Magburaka Tefeya Mape Yomadu Bodou Lol Rogberi Lunsar Matotoka Rokel Bridge Masingbi Koundou Lungi Koidu-Sefadu Pepel Yengema li Njaiama- e SIERRA LEONE M Freetown o 8o 30' Masiaka Sewafe Njaiama 8 30' Goderich Wellington Gandorhun a Yonibana Mile 91 Tungie o Magbuntuso Makite Yele M Koindu Hastings Songo EASTERN Buedu WESTERN Waterloo Mongeri York Bradford Falla AREA Tongo Giehun Kailahun Tolobo ia Boajibu Rotifunk a T Taiama Panguma Manowa Banana Is. Yawri Moyamba Dambara Bay Njala Lago Bendu Pendembu 8o 00' Mano Mano 8o 00' Sembehun Bo Gerihun Jct. -

Taylor Trial Transcript

Case No. SCSL-2003-01-T THE PROSECUTOR OF THE SPECIAL COURT V. CHARLES GHANKAY TAYLOR TUESDAY, 5 FEBRUARY 2008 9.30 A.M. TRIAL TRIAL CHAMBER II Before the Judges: Justice Teresa Doherty, Presiding Justice Richard Lussick Justice Julia Sebutinde Justice Al Hadji Malick Sow, Alternate For Chambers: Mr Simon Meisenberg Ms Doreen Kiggundu For the Registry: Ms Rachel Irura For the Prosecution: Ms Brenda J Hollis Mr Mohamed A Bangura Mr Christopher Santora Ms Maja Dimitrova Ms Kirsten Keith For the accused Charles Ghankay Mr Terry Munyard Taylor: Mr Andrew Cayley CHARLES TAYLOR Page 3066 05 FEBRUARY 2008 OPEN SESSION 1 Tuesday, 5 February 2008 2 [Open session] 3 [The accused present] 4 [Upon commencing at 9.30 a.m.] 09:28:45 5 PRESIDING JUDGE: Good morning. I notice a change of 6 appearance on your side, Mr Bangura. 7 MR BANGURA: Yes, your Honour. Appearing for the 8 Prosecution this morning, your Honour, Brenda J Hollis, myself 9 Mohamed A Bangura, Chris Santora and Maja Dimitrova. 09:29:08 10 PRESIDING JUDGE: I think the Defence bench remains the 11 same. 12 MR CAYLEY: Yes, your Honour, we're the same as yesterday, 13 Mr Munyard and myself Mr Cayley. Thank you. 14 PRESIDING JUDGE: If there are no other matters I will 09:29:18 15 remind the witness of his oath. 16 Mr Witness, you recall that yesterday you took the oath and 17 swore to tell the truth. That oath is still binding on you and 18 you must continue to answer questions truthfully.