An Australian Sight Record of Wilson's Phalarope by F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Migratory Shorebirds Management Plan

Report GLNG Curtis Island Marine Facilities Migratory Shorebirds Environmental Management Plan 17 MARCH 2011 Prepared for GLNG Operations Pty Ltd Level 22 Santos Place 32 Turbot Street Brisbane Qld 4000 42626727 Project Manager: URS Australia Pty Ltd Level 16, 240 Queen Street Angus McLeod Brisbane, QLD 4000 Senior Ecologist GPO Box 302, QLD 4001 Australia T: 61 7 3243 2111 Principal-In-Charge: F: 61 7 3243 2199 Chris Pigott Senior Principal Author: Angus McLeod Senior Ecologist Reviewer: Date: 17 March 2011 Reference: 42626727/01/03 Status: Final Chris Pratt Principal Environmental Scientist j:\jobs\42626727\5 works\draft emp\for tina 17.3.11\3310-glng-3-3 3-0065_shorebirds_final_17 03 2011.doc Table of Contents Abbreviations............................................................................................................iii Executive Summary..................................................................................................iv 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................1 1.1 Project Background .........................................................................................1 1.2 Purpose of the Migratory Shorebirds Environment Management Plan ...................................................................................................................1 1.3 Aims and Objectives ........................................................................................3 1.4 Study Area ........................................................................................................3 -

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List The target species list (species to be surveyed) should not change over the course of the study, therefore determining the target species list is an important project design task. Because waterbirds, including shorebirds, can occur in very high numbers in a census area, it is often not possible to count all species without compromising the quality of the survey data. For the basic shorebird census program (protocol 1), we recommend counting all shorebirds (sub-Order Charadrii), all raptors (hawks, falcons, owls, etc.), Common Ravens, and American Crows. This list of species is available on our field data forms, which can be downloaded from this site, and as a drop-down list on our online data entry form. If a very rare species occurs on a shorebird area survey, the species will need to be submitted with good documentation as a narrative note with the survey data. Project goals that could preclude counting all species include surveys designed to search for color-marked birds or post- breeding season counts of age-classed bird to obtain age ratios for a species. When conducting a census, you should identify as many of the shorebirds as possible to species; sometimes, however, this is not possible. For example, dowitchers often cannot be separated under censuses conditions, and at a distance or under poor lighting, it may not be possible to distinguish some species such as small Calidris sandpipers. We have provided codes for species combinations that commonly are reported on censuses. Combined codes are still species-specific and you should use the code that provides as much information as possible about the potential species combination you designate. -

List of Shorebird Profiles

List of Shorebird Profiles Pacific Central Atlantic Species Page Flyway Flyway Flyway American Oystercatcher (Haematopus palliatus) •513 American Avocet (Recurvirostra americana) •••499 Black-bellied Plover (Pluvialis squatarola) •488 Black-necked Stilt (Himantopus mexicanus) •••501 Black Oystercatcher (Haematopus bachmani)•490 Buff-breasted Sandpiper (Tryngites subruficollis) •511 Dowitcher (Limnodromus spp.)•••485 Dunlin (Calidris alpina)•••483 Hudsonian Godwit (Limosa haemestica)••475 Killdeer (Charadrius vociferus)•••492 Long-billed Curlew (Numenius americanus) ••503 Marbled Godwit (Limosa fedoa)••505 Pacific Golden-Plover (Pluvialis fulva) •497 Red Knot (Calidris canutus rufa)••473 Ruddy Turnstone (Arenaria interpres)•••479 Sanderling (Calidris alba)•••477 Snowy Plover (Charadrius alexandrinus)••494 Spotted Sandpiper (Actitis macularia)•••507 Upland Sandpiper (Bartramia longicauda)•509 Western Sandpiper (Calidris mauri) •••481 Wilson’s Phalarope (Phalaropus tricolor) ••515 All illustrations in these profiles are copyrighted © George C. West, and used with permission. To view his work go to http://www.birchwoodstudio.com. S H O R E B I R D S M 472 I Explore the World with Shorebirds! S A T R ER G S RO CHOOLS P Red Knot (Calidris canutus) Description The Red Knot is a chunky, medium sized shorebird that measures about 10 inches from bill to tail. When in its breeding plumage, the edges of its head and the underside of its neck and belly are orangish. The bird’s upper body is streaked a dark brown. It has a brownish gray tail and yellow green legs and feet. In the winter, the Red Knot carries a plain, grayish plumage that has very few distinctive features. Call Its call is a low, two-note whistle that sometimes includes a churring “knot” sound that is what inspired its name. -

First Record of the Terek Sandpiper in California

FIRST RECORD OF THE TEREK SANDPIPER IN CALIFORNIA ERIKA M. WILSON, 1400 S. BartonSt. #421, Arlington,Virginia 22204 BETTIE R. HARRIMAN, 5188 BittersweetLane, Oshkosh,Wisconsin 54901 On 28 August 1988, while birding at Carmel River State Beach, MontereyCounty, California(36032 ' N, 121057' W), we discoveredan adult Terek Sandpiper (Xenus cinereus). We watched this Eurasian vagrantbetween 1110 and 1135 PDT; we saw it again,along with local birders, between 1215 and 1240 as it foraged on the open beach. Wilson observedthe bird a third time on 5 September 1988 between 1000 and 1130; otherssaw it regularlyuntil 23 September1988. During our first observationa light overcastsky resultedin good viewingconditions, without glare or strongshadows. The weather was mild with a slightbreeze and some offshorefog. We found the Terek Sandpiperfeeding in the Carmel River'sshallow lagoon, separated from the Pacific Ocean by sand dunes. Its long, upturnedbill, quite out of keepingwith any smallwader with whichwe were familiar,immediately attracted our attention. We moved closer and tried unsuccessfullyto photographit. Shortlythereafter all the birdspresent took to the air. The sandpiperflew out over the dunesbut curvedback and landedout of sighton the open beach. We telephonedRobin Roberson,and half an hour later she, Brian Weed, Jan Scott, Bob Tinfie, and Ron Branson arrived,the lattertwo armedwith telephotolenses. We quicklyrelocated the TerekSandpiper on the beach,foraging at the surfline. The followingdescription is basedon our field notes,with color names takenfrom Smithe(197.5). Our bird was a medium-sizedsandpiper resemblinga winter-plumagedSpotted Sandpiper (Actitis rnacularia)but distinguishedby bright yellow-orangelegs and an upturnedbill (Figure1). The evenlycurved, dark horn bill, 1.5 timesthe lengthof the bird'shead, had a fleshyorange base. -

Terek Sandpiper (<I>Xenus Cinereis</I>): a First for Mexico

TerekSandpiper (Xenus cin s). a first for Mexico Daniel6alindo precipitationaveraging 200 mm (Garcia edge.The wingtipsextended backward 1964). to just reachthe tip of the tail. The un- CentroInterdisciplinario deCiencias Marinas On ll April 2002, Galindo locateda derpartswere white and unmarked.The TerekSandpiper (Xenus cinereus; Figure 1) legswere extremely bright yellowish-or- Av.Instituto Polit•cnico Nacional s/n at Chametla-El Centenario. This bird was ange.The lengthof the legs relativeto LaPaz, Baja California Sur23096 Mexico seenagain during late May 2002 Presum- the bird was shorter than that seen in ably the samebird wasrelocated there on most Tringaand approximatedthe pro- (email:[email protected]) 21 August 2002 and wasseen eleven more portionsof a SpottedSandpiper [Actitis times before it was last recorded 10 Febru- macularius]. The bill was long and ary 2003.The TerekSandpiper fed mostly curved upward. Its length was 1.5 to Steven(•. Mlodinow in the intertidalzone, usuallyin mixed 1.75 times that of the head. The bill was flocks of Semipalmated Plovers largelyblackish, excepting a smallarea 4819Gardner Avenue (Charadriussemipalmatus) and Western of brightorange at the base.Brief flight Sandpipers(Calidris mauri). On four occa- views revealeda thick white trailing Everett,Washington 98203 sions, it was observed roosting at the edgeto the secondariesthat extendedas supralittoralzone, amonga flock of Semi- a narrower whitish area onto the inner- (email:[email protected]) palmated Plovers. Throughout its stay,it mostseveral primaries. The rump and appearedto be in goodhealth, feeding and uppertailcoverts were gray, The rectrices flyingwithout apparent problems. were gray with whitish barringon the RobertoCarmona The followingis a descriptionof the En- outer portionof the outer web of each senadade La PazTerek Sandpiper based on rectrix(which provided a whitishouter LuisSauma fieldnotes and videotapeby SGMfrom 29 border to the tail as a whole). -

Wilson's Phalarope in Cornwall.—Early on the Morning of 15 Th June 1961 J.E.B

Notes Wilson's Phalarope in Cornwall.—Early on the morning of 15 th June 1961 J.E.B. came across an unfamiliar medium-sized wader with plain brown upper-parts and a dull white rump and tail, on Marazion Marsh, Cornwall. He contacted Dr. G. Allsop and between them they continued... 183 BRITISH BIRDS watched the bird for about five hours. N. R. Phillips was then told and he and R. Khan saw it that evening. Two days later it was found independently by W.R.P.B. and J.L.F.P., and subsequently a number of other observers went to see it. It was last recorded with certainty on 4th July. It was recognised as a species of phalarope by its charac teristic position when swimming and by the delicate proportions of its head, neck and bill, while its relatively large size, comparatively drab coloration and distinctive face-pattern together proclaimed it a male Wilson's Phalarope (Phalaropus tricolor). The detailed descrip tion which follows is based mainly on that obtained by W.R.P.B. and J.F.L.P. on 17th June, but the notes made by J.E.B. and others agree well with it: An unusuaEy large, long-legged, long-billed phalarope, perhaps approximating in size to a small Reeve {Philomachus pugnax) or a Wood Sandpiper (Tringa glanold), and behaving rather like those species, feeding mainly by wading along the shore rather than swimming, and having a loose, erratic, wavering flight. Forehead, crown and hind-neck ash-grey with an inconspicuous paler longitudinal patch on the nape. -

Great Salt Lake FAQ June 2013 Natural History Museum of Utah

Great Salt Lake FAQ June 2013 Natural History Museum of Utah What is the origin of the Great Salt Lake? o After the Lake Bonneville flood, the Great Basin gradually became warmer and drier. Lake Bonneville began to shrink due to increased evaporation. Today's Great Salt Lake is a large remnant of Lake Bonneville, and occupies the lowest depression in the Great Basin. Who discovered Great Salt Lake? o The Spanish missionary explorers Dominguez and Escalante learned of Great Salt Lake from the Native Americans in 1776, but they never actually saw it. The first white person known to have visited the lake was Jim Bridger in 1825. Other fur trappers, such as Etienne Provost, may have beaten Bridger to its shores, but there is no proof of this. The first scientific examination of the lake was undertaken in 1843 by John C. Fremont; this expedition included the legendary Kit Carson. A cross, carved into a rock near the summit of Fremont Island, reportedly by Carson, can still be seen today. Why is the Great Salt Lake salty? o Much of the salt now contained in the Great Salt Lake was originally in the water of Lake Bonneville. Even though Lake Bonneville was fairly fresh, it contained salt that concentrated as its water evaporated. A small amount of dissolved salts, leached from the soil and rocks, is deposited in Great Salt Lake every year by rivers that flow into the lake. About two million tons of dissolved salts enter the lake each year by this means. Where does the Great Salt Lake get its water, and where does the water go? o Great Salt Lake receives water from four main rivers and numerous small streams (66 percent), direct precipitation into the lake (31 percent), and from ground water (3 percent). -

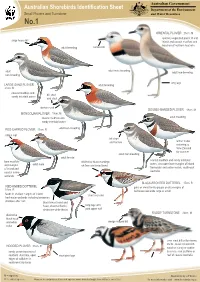

Australian Shorebirds Identification Sheet Department of the Environment Small Plovers and Turnstone and Water Resources No.1

Australian Government Australian Shorebirds Identification Sheet Department of the Environment Small Plovers and Turnstone and Water Resources No.1 ORIENTAL PLOVER 25cm. M sparsely vegetated plains of arid large heavy bill inland and coastal mudflats and beaches of northern Australia adult breeding narrow bill adult male breeding adult adult non-breeding non-breeding long legs LARGE SAND PLOVER adult breeding 21cm. M coastal mudflats and bill short sandy intertidal zones and stout darker mask DOUBLE-BANDED PLOVER 19cm. M MONGOLIAN PLOVER 19cm. M coastal mudflats and adult breeding sandy intertidal zones RED-CAPPED PLOVER 15cm. R adult non-breeding rufous cap bill short and narrow winter visitor returning to New Zealand for summer adult non-breeding adult female coastal mudflats and sandy intertidal bare mudflats distinctive black markings zones, also open bare margins of inland and margins adult male on face and breastband of inland and freshwater and saline marsh, south-east coastal saline Australia wetlands BLACK-FRONTED DOTTEREL 17cm. R RED-KNEED DOTTEREL pairs or small family groups on dry margins of 18cm. R feshwater wetlands large or small feeds in shallow margins of inland short rear end freshwater wetlands including temporary shallows after rain black breast band and head, chestnut flanks, long legs with distinctive white throat pink upper half RUDDY TURNSTONE 23cm. M distinctive black hood and white wedge shaped bill collar uses stout bill to flip stones, shells, seaweed and drift- 21cm. R HOODED PLOVER wood on sandy or cobble sandy ocean beaches of beaches, rock platform or southern Australia, open short pink legs reef of coastal Australia edges of saltlakes in south-west Australia M = migratory . -

Mate Guarding, Copulation Strategies and Paternity in the Sex-Role Reversed, Socially Polyandrous Red-Necked Phalarope Phalaropus Lobatus

Behav Ecol Sociobiol (2004) 57:110–118 DOI 10.1007/s00265-004-0825-2 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Douglas Schamel · Diane M. Tracy · David B. Lank · David F. Westneat Mate guarding, copulation strategies and paternity in the sex-role reversed, socially polyandrous red-necked phalarope Phalaropus lobatus Received: 1 January 2004 / Revised: 7 June 2004 / Accepted: 23 June 2004 / Published online: 11 August 2004 Springer-Verlag 2004 Abstract In a recent review, Westneat and Stewart tempts were usually thwarted by the female. Paired males (2003) compiled evidence that extra-pair paternity results sought extra-pair copulations with females about to re- from a three-player interaction in which sexual conflict is enter the breeding pool. Multilocus DNA fingerprinting a potent force. Sequentially polyandrous species of birds showed that 6% of clutches (4/63) each contained one appear to fit this idea well. Earlier breeding males may chick sired by a male other than the incubator, producing attempt to use sperm storage by females to obtain pater- a population rate of these events of 1.7% (n=226 chicks). nity in their mate’s subsequent clutches. Later-breeding Male mates had full paternity in all first clutches (n=25) males may consequently attempt to avoid sperm compe- and 15 of 16 monogamous replacement clutches. In con- tition by preferring to pair with previously unmated fe- trast, 3 of 6 clutches of second males contained extra-pair males. Females may bias events one way or the other. young likely fathered by the female’s previous mate. We examined the applicability of these hypotheses by Previously mated female phalaropes may employ counter- studying mating behavior and paternity in red-necked strategies that prevent later mating males from discrim- phalaropes (Phalaropus lobatus), a sex-role reversed, inating against them. -

First Record of Long-Billed Curlew Numenius Americanus in Peru and Other Observations of Nearctic Waders at the Virilla Estuary Nathan R

Cotinga 26 First record of Long-billed Curlew Numenius americanus in Peru and other observations of Nearctic waders at the Virilla estuary Nathan R. Senner Received 6 February 2006; final revision accepted 21 March 2006 Cotinga 26(2006): 39–42 Hay poca información sobre las rutas de migración y el uso de los sitios de la costa peruana por chorlos nearcticos. En el fin de agosto 2004 yo reconocí el estuario de Virilla en el dpto. Piura en el noroeste de Peru para identificar los sitios de descanso para los Limosa haemastica en su ruta de migración al sur y aprender más sobre la migración de chorlos nearcticos en Peru. En Virilla yo observí más de 2.000 individuales de 23 especios de chorlos nearcticos y el primer registro de Numenius americanus de Peru, la concentración más grande de Limosa fedoa en Peru, y una concentración excepcional de Limosa haemastica. La combinación de esas observaciones y los resultados de un estudio anterior en el invierno boreal sugiere la posibilidad que Virilla sea muy importante para chorlos nearcticos en Peru. Las observaciones, también, demuestren la necesidad hacer más estudios en la costa peruana durante el año entero, no solemente durante el punto máximo de la migración de chorlos entre septiembre y noviembre. Shorebirds are poorly known in Peru away from bordered for a few hundred metres by sand and established study sites such as Paracas reserve, gravel before low bluffs rise c.30 m. Very little dpto. Ica, and those close to metropolitan areas vegetation grows here, although cows, goats and frequented by visiting birdwatchers and tour pigs owned by Parachique residents graze the area. -

Supplementary Material

Xenus cinereus (Terek Sandpiper) European Red List of Birds Supplementary Material The European Union (EU27) Red List assessments were based principally on the official data reported by EU Member States to the European Commission under Article 12 of the Birds Directive in 2013-14. For the European Red List assessments, similar data were sourced from BirdLife Partners and other collaborating experts in other European countries and territories. For more information, see BirdLife International (2015). Contents Reported national population sizes and trends p. 2 Trend maps of reported national population data p. 3 Sources of reported national population data p. 5 Species factsheet bibliography p. 6 Recommended citation BirdLife International (2015) European Red List of Birds. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. Further information http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/info/euroredlist http://www.birdlife.org/europe-and-central-asia/european-red-list-birds-0 http://www.iucnredlist.org/initiatives/europe http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/conservation/species/redlist/ Data requests and feedback To request access to these data in electronic format, provide new information, correct any errors or provide feedback, please email [email protected]. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ BirdLife International (2015) European Red List of Birds Xenus cinereus (Terek Sandpiper) Table 1. Reported national breeding population size and trends in Europe1. Country (or Population estimate Short-term population trend4 -

Biometrics and Breeding Phenology of Terek Sandpipers in the Pripyat’ Valley, S Belarus

54 Wader Study Group Bulletin Biometrics and breeding phenology of Terek Sandpipers in the Pripyat’ Valley, S Belarus NATALIA KARLIONOVA1, MAGDALENA REMISIEWICZ2, PAVEL PINCHUK1 1Institute of Zoology, Belarussian National Academy of Sciences, Academichnaya Str. 27, 220072 Minsk, Belarus. [email protected] 2Avian Ecophysiology Unit, Dept of Vertebrate Ecology and Zoology, Univ. of Gdansk, al. Legionów 9, 80-441 Gdansk, Poland. [email protected] Karlionova, N., Remisiewicz, M. & Pinchuk, P. 2006. Biometrics and breeding phenology of Terek Sandpipers in the Pripyat’ Valley, S Belarus. Wader Study Group Bull. 110: 54–58. Keywords: Terek Sandpiper, Xenus cinereus, biometrics, breeding phenology, Pripyat’ Valley, Belarus We present data on the breeding phenology and biometrics of Terek Sandpipers from the isolated westernmost population in the Pripyat’ river valley, S Belarus, close to the border with Ukraine. Studies were conducted on floodplain islands between the beginning of April and mid-July during 1996–1999 and 2002–2006. Over the years, the first arrivals appeared during 10–26 April (median 14 April), first eggs were laid during 24 April to 5 May (median 30 April) and the latest egg was laid on 25 May, first chicks hatched during 19 May to 1 June (median 25 May) and the first fledged juveniles were caught on 23 June. We present biometric data for juve- niles (at the post-fledging stage) and adults. The mean wing length of juveniles, just before departure from the breeding grounds in mid June, reached 96% of that of adults. Juvenile total head lengths were 91% of adult, and bill and nalospi lengths 85% of adult, but tarsus and tarsus plus toe lengths were the same as adults.