Bronze Bell Wreck”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

West of Wales Shoreline Management Plan 2 Section 4

West of Wales Shoreline Management Plan 2 Section 4. Coastal Area D November 2011 Final 9T9001 A COMPANY OF HASKONING UK LTD. COASTAL & RIVERS Rightwell House Bretton Peterborough PE3 8DW United Kingdom +44 (0)1733 334455 Telephone Fax [email protected] E-mail www.royalhaskoning.com Internet Document title West of Wales Shoreline Management Plan 2 Section 4. Coastal Area D Document short title Policy Development Coastal Area D Status Final Date November 2011 Project name West of Wales SMP2 Project number 9T9001 Author(s) Client Pembrokeshire County Council Reference 9T9001/RSection 4CADv4/303908/PBor Drafted by Claire Earlie, Gregor Guthrie and Victoria Clipsham Checked by Gregor Guthrie Date/initials check 11/11/11 Approved by Client Steering Group Date/initials approval 29/11/11 West of Wales Shoreline Management Plan 2 Coastal Area D, Including Policy Development Zones (PDZ) 10, 11, 12 and 13. Sarn Gynfelyn to Trwyn Cilan Policy Development Coastal Area D 9T9001/RSection 4CADv4/303908/PBor Final -4D.i- November 2011 INTRODUCTION AND PROCESS Section 1 Section 2 Section 3 Introduction to the SMP. The Environmental The Background to the Plan . Principles Assessment Process. Historic and Current Perspective . Policy Definition . Sustainability Policy . The Process . Thematic Review Appendix A Appendix B SMP Development Stakeholder Engagement PLAN AND POLICY DEVELOPMENT Section 4 Appendix C Introduction Appendix E Coastal Processes . Approach to policy development Strategic Environmental . Division of the Coast Assessment -

Welsh Wreck Web Research Project (North Cardigan Bay) On-Line Research Into the Wreck of The: Danube

Welsh Wreck Web Research Project (North Cardigan Bay) On-line research into the wreck of the: Danube A Quebec Fully Rigged Ship. (Believed to be similar to the Danube) Report compiled by: Malcolm Whitewright Welsh Wreck Web Research Project Nautical Archaeology Society Report Title: Welsh Wreck Web Research Project (North Cardigan Bay) On-line research into the wreck of the ship: Danube Compiled by: Malcolm Whitewright 14 St Brides Road Little Haven Haverfordwest Pembrokeshire SA62 3UN Tel: +44 (0)7879814022 E-mail: [email protected] On behalf of: Nautical Archaeology Society Fort Cumberland Fort Cumberland Road Portsmouth PO4 9LD Tel: +44 (0)23 9281 8419 E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.nauticalarchaeologysociety.org Managed by: Malvern Archaeological Diving Unit 17 Hornyold Road Malvern Worcestershire WR14 1QQ Tel: +44 (0)1684 574774 E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.madu.org.uk Date: October 2020 2 Welsh Wreck Web Research Project Nautical Archaeology Society 1.0 Abstract This project is to discover information relating to the reported wreck of the Full Rigged Ship Danube (MADU Ref. 155. Fig. 1) for which there are several newspaper archived reports of it having gone aground on 6th March 1861 on St Patrick’s Causeway, Cardiganshire, Wales. The objective is to establish the facts relating to the wreck report and discover the circumstances leading up to the wrecking and the outcome, together with any other relevant information. The research is limited to information available on-line as access to libraries and record offices was not possible at this time due to the lockdown for the CORVID- 19 pandemic. -

7. Dysynni Estuary

West of Wales Shoreline Management Plan 2 Appendix D Estuaries Assessment November 2011 Final 9T9001 Haskoning UK Ltd West Wales SMP2: Estuaries Assessment Date: January 2010 Project Ref: R/3862/1 Report No: R1563 Haskoning UK Ltd West Wales SMP2: Estuaries Assessment Date: January 2010 Project Ref: R/3862/1 Report No: R1563 © ABP Marine Environmental Research Ltd Version Details of Change Authorised By Date 1 Draft S N Hunt 23/09/09 2 Final S N Hunt 06/10/09 3 Final version 2 S N Hunt 21/01/10 Document Authorisation Signature Date Project Manager: S N Hunt Quality Manager: A Williams Project Director: H Roberts ABP Marine Environmental Research Ltd Suite B, Waterside House Town Quay Tel: +44(0)23 8071 1840 SOUTHAMPTON Fax: +44(0)23 8071 1841 Hampshire Web: www.abpmer.co.uk SO14 2AQ Email: [email protected] West Wales SMP2: Estuaries Assessment Summary ABP Marine Environmental Research Ltd (ABPmer) was commissioned by Haskoning UK Ltd to undertake the Appendix F assessment component of the West Wales SMP2 which covers the section of coast between St Anns Head and the Great Orme including the Isle of Anglesey. This assessment was undertaken in accordance with Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) guidelines (Defra, 2006a). Because of the large number of watercourses within the study area a screening exercise was carried out which identified all significant watercourses within the study area and determined whether these should be carried through to the Appendix F assessment. The screening exercise identified that the following watercourses should be subjected to the full Appendix F assessment: . -

Traces of Submerged Lands on the Coasts of Lancashire, Cheshire And

KAmxC. Vol PLATE <ssmi¥//V<s /K&sfjYr CMjrl/yffe. //wns //y/z> Jifef^ 5.r." Cf/r/Jkv 4V/> i//f-j of/>FOifM/<£ Mp of /3/i/m/i (afar /)f/-f//a?s a/VP /a&r Tonfifa. fieaa maris M . I law /r/HtK/jxy /6THce/vrufty SHOtVWC ROMS OVE/S ""yxM. fk-V; BELISAMA Pftejeur CoMr mum froienls f1/>/>. Geoioc/c/n Coffsr LiNes. ftf/srocene ff/t/oo lllllll SETEIA TISOBiVS Btvrdd //rtfwr. \eion PARCH y /1/eitcH l©?NOVIUM J{.PoRTH I £<?//>&/ D/NOftWIC O SEGONTIUM Br/figfi Forfe. Oms D/nueu DEVA A'oman Forts. Roman Stations Lost Tonvns Port/) D/n//cren. lojT l/f/VDj, l/n/rj of FmfMj M#P. I ... 11',^] SARN B,4B«>!' iiniHilliOlllvy f 1 fii/V /'ffM 700 yards Conway <{'• Ca&r'Cefa/fyT MELKS FORTRESS OHL HOLyHP/ID /^OUNTfll/4 T. 3LL lr0 I'TH. TRACES OF SUBMERGED LANDS ON THE COASTS OF LANCASHIRE, CHESHIRE, AND NORTH WALES. By Edward W. Cox. Read 23rd March, 1893. GEOLOGY. T would be well if this paper could be prefaced I by a geological lecture, dealing with the causes of change in the levels of land and the coast-lines of Britain from the latest geological age, when man first appeared on the earth to replenish and subdue it, down to the present time, in order to prove the continuity and vastness of extent to which these forces worked. I can do no more than take them for granted, and refer to them in the briefest possible way, to show that only a small part of the great whole is contained within the limits of comparatively recent history and tradition with which we have to deal. -

DWYRYD ESTUARY and MORFA HARLECH Component Lcas (Snowdonia): Morfa Harlech; Vale of Ffestiniog; Morfa Dyffryn Component Lcas (Gwynedd): Porthmadog

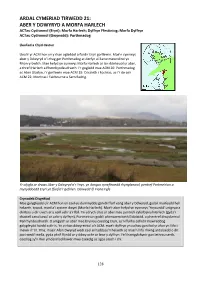

SEASCAPE CHARACTER AREA 21: DWYRYD ESTUARY AND MORFA HARLECH Component LCAs (Snowdonia): Morfa Harlech; Vale of Ffestiniog; Morfa Dyffryn Component LCAs (Gwynedd): Porthmadog Location and Context This SCA is located in the northern part of the west Snowdonia coast. It includes the Dwyryd estuary from its mouth near Porthmadog to its inland tidal limit at Tan-y-bwlch. It also includes Morfa Harlech on the southern shore of the estuary, and the towns of Harlech and Penrhyndeudraeth. To the north is SCA 20: Porthmadog and Glaslyn Estuary, to the west is SCA 19: Criccieth to Mochras, and to the south is SCA 22: Mochras to Fairbourne and Sarn Badrig. View across the Dwyryd Estuary from Ynys, showing intertidal habitats, the village of Portmeirion and the mountains of Snowdonia forming the backdrop. Image © Fiona Fyfe Summary Description Views of this SCA are dominated by the broad landform of the Dwyryd estuary, with its extensive salt marshes, sand, mud and dune system (Morfa Harlech). The estuary also contains distinctive ‘islands’ and ridges of higher ground on either side. Overlooking the estuary are the contrasting villages of Harlech (with its Medieval castle on the valley side), Portmeirion with its Italianate architecture, and the industrial village of Penrhyndeudraeth. Surrounding the estuary are the wooded hills of Snowdonia, which form a majestic backdrop to picturesque views from lower land. In the eastern part of SCA, the valley narrows as the river flows inland. Here, the Afon Dwyryd has been heavily modified flows between areas of improved grazing, with main roads on both sides of the valley floor. -

Pen Llŷn A'r Sarnau Candidate Sac Draft Management Plan Contents List

Pen Ll_n a’r Sarnau cSAC: Management Plan, Consultation Draft (Contents list) August 2000 PEN LLŶN A’R SARNAU CANDIDATE SAC DRAFT MANAGEMENT PLAN CONTENTS LIST 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Legal background: Where do SACs come from and what legal obligations do they entail?…………. .................................................................................. ………….I.1 1.1.1 The Habitats Directive.................................................................................... I.1 1.1.2 The Habitats Regulations ................................................................................ I.1 1.2 Selection of the Pen Ll_n a’r Sarnau cSAC ................................................................ I.2 1.3 Preparation of management schemes .......................................................................... I.2 1.4 Competent and relevant authorities............................................................................. I.3 1.4.1 Relevant authorities ....................................................................................... I.3 1.4.2 Competent authorities .................................................................................... I.4 1.5 Liaison framework for the cSAC ................................................................................ I.5 1.6 The UK Marine SACs Project .................................................................................... I.6 2.0 SITE DESCRIPTION 2.1 Site location and boundary ..................................................…......................................II.1 -

Marine Character Areas MCA 14 TREMADOG BAY & DWYRYD

Marine Character Areas MCA 14 TREMADOG BAY & DWYRYD ESTUARY Location and boundaries This Marine Character Area (MCA) encompasses the shallow waters of Tremadog Bay, nestled between the Llŷn Peninsula and the Snowdonia coast in north-west Wales. It includes the tidal extents of the Glaslyn and Dwyryd estuaries, up to the High Water Mark. The MCA is characterised by shallower waters (informed by bathymetry) and markedly lower wave climate/wave exposure compared with the surrounding MCAs. The rocky reef of Sarn Badrig forms the southern MCA boundary, with associated rough, shallow waters as marked on the Marine Charts. The coastal areas which form the northern boundary of the MCA are contained within NLCAs 4: Llŷn and 5: Tremadoc Bay. www.naturalresourceswales.gov.uk MCA 14 Tremadog Bay and Dwyryd Estuary - Page 1 of 9 Key Characteristics Key Characteristics A sweeping, shallow bay with wide sandy beaches, and a distinctive swash-aligned coastal landform at Morfa Harlech. To the north, the rugged coastal peak of Moel-y- Gest is a prominent landmark. Extensive intertidal area at the mouth of the Dwyryd estuary, with a meandering channel running through it, and continuing inland. Ynys Gifftan is located in the estuary. Shallow mud and sand substrate overlying Oligocene and Permo-Triassic sedimentary rock with a diverse infaunal community. Traditionally, mariners used sounding leads on to follow the ‘muddy hollow’ from off St Tudwal’s East to Porthmadog fairway buoy. Includes part of the designated Lleyn Peninsula and the Sarnau SAC, recognised for its reefs, shallow inlets and estuaries. Extensive intertidal habitats and river channels designated SAC and SSSI (Morfa Harlech and Glaslyn) provide important bird feeding and overwintering sites and habitat for rare plants and insects. -

The Shore Fauna of Cardigan Bay. by Chas

" [ 102 J The Shore Fauna of Cardigan Bay. By Chas. L. Walton, University College of Wales, Aberystwyth. 'OARDIGANBAY occupies a considerable portion of the west coast of Wales. It is bounded on the north by the southern shores of Oarnarvon- shire; its central portion comprises the entire coast-lines of Merioneth and Oardigan, and its southern limit is the north coast of Pembrokeshire. The total length of coast-line between Bmich-y-pwll in Oarnarvon, and Strumble Head in Pembrokeshire, is about 140 miles, and in addition there are considerable estuarine areas. The entire Bay is shallow; for the most part four to ten fathoms inshore, and ten to sixteen about the centre. It is considered probable that the Bay was temporarily transformed into low-lying land by accumulations of boulder clay during the Ice !ge. Wave action has subsequently completed the erosive removal of that land area, with the exception of a few patches on the present coast-line and certain causeways or sarns. Portions of the sea-floor probably still retain some remains of this drift, and owing to the shallowness, tidal cur- rents and wave disturbance speedily cause the waters ofthe Bay to become -opaque. The prevailing winds are, as usual, south-westerly, and heavy .surf is frequent about the central shore-line. This surf action is accen- tuated by the large amount of shingle derived from the boulder clay. The action of the prevailing winds and set of drifts in the Bay results in the constant movement northwards along the shores of a very considerable quantity of this residual drift material. -

Marine Character Areas MCA 14 TREMADOG BAY & DWYRYD

Marine Character Areas MCA 14 TREMADOG BAY & DWYRYD ESTUARY Location and boundaries This Marine Character Area (MCA) encompasses the shallow waters of Tremadog Bay, nestled between the Llŷn Peninsula and the Snowdonia coast in north-west Wales. It includes the tidal extents of the Glaslyn and Dwyryd estuaries, up to the High Water Mark. The MCA is characterised by shallower waters (informed by bathymetry) and markedly lower wave climate/wave exposure compared with the surrounding MCAs. The rocky reef of Sarn Badrig forms the southern MCA boundary, with associated rough, shallow waters as marked on the Marine Charts. The coastal areas which form the northern boundary of the MCA are contained within NLCAs 4: Llŷn and 5: Tremadoc Bay. www.naturalresourceswales.gov.uk MCA 14 Tremadog Bay and Dwyryd Estuary - Page 1 of 9 Key Characteristics Key Characteristics A sweeping, shallow bay with wide sandy beaches, and a distinctive swash-aligned coastal landform at Morfa Harlech. To the north, the rugged coastal peak of Moel-y- Gest is a prominent landmark. Extensive intertidal area at the mouth of the Dwyryd estuary, with a meandering channel running through it, and continuing inland. Ynys Gifftan is located in the estuary. Shallow mud and sand substrate overlying Oligocene and Permo-Triassic sedimentary rock with a diverse infaunal community. Traditionally, mariners used sounding leads on to follow the ‘muddy hollow’ from off St Tudwal’s East to Porthmadog fairway buoy. Includes part of the designated Lleyn Peninsula and the Sarnau SAC, recognised for its reefs, shallow inlets and estuaries. Extensive intertidal habitats and river channels designated SAC and SSSI (Morfa Harlech and Glaslyn) provide important bird feeding and overwintering sites and habitat for rare plants and insects. -

Asynchronous Retreat Dynamics Between the Irish Sea Ice Stream and Terrestrial Outlet Glaciers

Earth Surf. Dynam., 1, 53–65, 2013 Open Access www.earth-surf-dynam.net/1/53/2013/ Earth Surface doi:10.5194/esurf-1-53-2013 © Author(s) 2013. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Dynamics Rapid marine deglaciation: asynchronous retreat dynamics between the Irish Sea Ice Stream and terrestrial outlet glaciers H. Patton1, A. Hubbard1, T. Bradwell2, N. F. Glasser1, M. J. Hambrey1, and C. D. Clark3 1Institute of Geography and Earth Sciences, Aberystwyth University, Aberystwyth, SY23 3DB, UK 2British Geological Survey, Murchison House, West Mains Road, Edinburgh, EH9 3LA, UK 3Department of Geography, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, S10 2TN, UK Correspondence to: H. Patton ([email protected]) Received: 24 July 2013 – Published in Earth Surf. Dynam. Discuss.: 23 August 2013 Revised: 31 October 2013 – Accepted: 15 November 2013 – Published: 3 December 2013 Abstract. Understanding the retreat behaviour of past marine-based ice sheets provides vital context for ac- curate assessments of the present stability and long-term response of contemporary polar ice sheets to climate and oceanic warming. Here new multibeam swath bathymetry data and sedimentological analysis are combined with high resolution ice-sheet modelling to reveal complex landform assemblages and process dynamics asso- ciated with deglaciation of the Celtic ice sheet within the Irish Sea Basin. Our reconstruction indicates a non- linear relationship between the rapidly receding Irish Sea Ice Stream and the retreat of outlet glaciers draining the adjacent, terrestrially based ice cap centred over Wales. Retreat of Welsh ice was episodic; superimposed over low-order oscillations of its margin are asynchronous outlet readvances driven by catchment-wide mass balance variations that are amplified through migration of the ice cap’s main ice divide. -

Maritime Introduction

A Research Framework for the Archaeology of Wales VERSION 03 Final Refresh document February 2017 Maritime Introduction ‘In any pre-industrial society, from the upper Palaeolithic to the nineteenth century AD, a boat or (later) a ship was the largest and most complex machine produced... But such a dominating position for maritime activities has not been limited to the technical sphere; in many societies it has pervaded every aspect of social organisation... the course of human history has owed not a little to maritime activities, and their study must constitute an important element in the search of a greater understanding of man’s past.’ - Muckleroy, K, 1978, Maritime Archaeology, 3 Whilst shipwrecks capture the imagination, they are only a small part of a broad spectrum of marine historic environment assets encompassed by ‘maritime’. Just as remarkable are our submerged and intertidal landscapes containing evidence for the past use of the coast. Lasting cultural associations to these lands, now lost to sea-level rise, are the legends known to every Welsh schoolchild – such as Cantre’r Gwaelod (The Lowland Hundred) encompassing much of Cardigan Bay and Caer Arianhod, a rock formation off Dinas Dinlle, reputed to have been the site of a palace. To reflect this diversity, this fifth-year Review of the Maritime chapter of the Research Framework for the Archaeology of Wales has been approached from the perspective of ‘maritime culture landscapes’ – an ‘umbrella’ term relating to our understanding of the use of the sea by humans, encompassing both physical evidence and cultural associations. Related research comprises archaeology, history, ethnography, the exploration of oral traditions, and the study of material culture, as well as geological and archaeological sciences. -

ACM 21 I ACM 25 T128-160

ARDAL CYMERIAD TIRWEDD 21: ABER Y DDWYRYD A MORFA HARLECH ACTau Cydrannol (Eryri): Morfa Harlech; Dyffryn Ffestiniog; Morfa Dyffryn ACTau Cydrannol (Gwynedd): Porthmadog Lleoliad a Chyd destun Lleolir yr ACM hon yn y rhan ogleddol arfordir Eryri gorllewin. Mae'n cynnwys aber y Ddwyryd o'i cheg ger Porthmadog at derfyn ei llanw mewndirol yn Nhan-y-bwlch. Mae hefyd yn cynnwys Morfa Harlech ar lan ddeheuol yr aber, a threfi Harlech a Phenrhyndeudraeth. I'r gogledd mae ACM 20: Porthmadog ac Aber Glaslyn, i'r gorllewin mae ACM 19: Criccieth i Fochras, ac i'r de ceir ACM 22: Mochras i Fairbourne a Sarn Badrig. Yr olygfa ar draws Aber y Ddwyryd o’r Ynys, yn dangos cynefinoedd rhynglanwol, pentref Portmeirion a mynyddoedd Eryri yn ffurfio’r gefnlen. Delwedd © Fiona Fyfe Crynodeb Disgrifiad Mae golygfeydd o’r ACM hon yn cael eu dominyddu gan dirffurf eang aber y Ddwyryd, gyda'i morfeydd heli helaeth, tywod, mwd a’i system dwyni (Morfa Harlech). Mae'r aber hefyd yn cynnwys 'Ynysoedd' unigryw a chribau o dir uwch ar y naill ochr a'r llall. Yn edrych dros yr aber mae pentrefi cyferbyniol Harlech (gyda'i chastell canoloesol ar ochr y dyffryn), Portmeirion gyda'i phensaernïaeth Eidalaidd, a phentref diwydiannol Penrhyndeudraeth. O amgylch yr aber mae bryniau coediog Eryri, sy'n ffurfio cefndir mawreddog golygfeydd hardd o dir is. Yn y rhan ddwyreiniol o'r ACM, mae'r dyffryn yn culhau gan fod yr afon yn llifo i mewn i'r tir. Yma, mae'r Afon Dwyryd wedi cael ei haddasu'n helaeth ac mae’n llifo rhwng ardaloedd o dir pori wedi'i wella, gyda phrif ffyrdd ar y ddwy ochr ar lawr y dyffryn.