Steve Reich: Music As a Gradual Process: Part I Author(S): K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

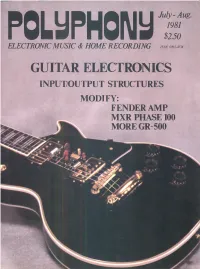

Guitar Electronics Input/Output Structures Modify: Fender Amp Mxr Phase 100 More Gr- 500 the Ultimate Keyboard

J u ly -Aug. 1981 PQLUPHONU $2 .5 0 ELECTRONIC MUSIC & HOME RECORDING ISSN: 0163-4534 GUITAR ELECTRONICS INPUT/OUTPUT STRUCTURES MODIFY: FENDER AMP MXR PHASE 100 MORE GR- 500 THE ULTIMATE KEYBOARD The Prophet-10 is the most complete keyboard instrument available today. The Prophet is a true polyphonic programmable synthesizer with 10 complete voices and 2 manuals. Each 5 voice keyboard has its own programmer allowing two completely different sounds to be played simultaneously. All ten voices can also be played from one keyboard program. Each voice has 2 voltage controlled oscillators, a mixer, a four pole low pass filter, two ADSR envelope generators, a final VCA and independent modula tion capabilities. The Prophet-10’s total capabilities are too The Prophet-10 has an optional polyphonic numerous to mention here, but some of the sequencer that can be installed when the Prophet features include: is ordered, or at a later date in the field. It fits * Assignable voice modes (normal, single, completely within the main unit and operates on double, alternate) the lower manual. Various features of the * Stereo and mono balanced and unbalanced sequencer are: outputs * Simplicity; just play normally & record ex * Pitch bend and modulation wheels actly what you play. * Polyphonic modulation section * 2500 note capability, and 6 memory banks. * Voice defeat system * Built-in micro-cassette deck for both se * Two assignable & programmable control quence and program storage. voltage pedals which can act on each man * Extensive editing & overdubbing facilities. ual independently * Exact timing can be programmed, and an * Three-band programmable equalization external clock can be used. -

Making Your Classroom Go

teaching OCTOBER 2015 VOLUME 23, NUMBER 2 A SMALL Makingmusicmusic Your BUT Classroom Go MIGHTY Music How to Program engage your students with the music “POP” of today TEACHING SINGERS to Sight-Read The Elementary and Secondary EDUCATION ACT QuaverFindOutAd_NAfME_Aug15.pdf 1 7/30/15 12:26 PM Find out what these districts already know... Quaver is revolutionizing music education! TM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Packed with nearly 1,000 Songs! Try 36 Lessons from our K-8 Curriculum! Just go to QuaverMusic.com/Preview and begin your FREE 30-day trial today! ©2015 QuaverMusic.com, LLC October 2015 Volume 23, Number 2 contentsMUSIC EDUCATION ● ORCHESTRATING SUCCESS Music students learn cooperation, discipline, and teamwork. 28 Teachers and students alike can rock out and learn with pop music! FEATURES 24 TEACHING SINGERS 28 POP AND ROCK GOES 32 EL SISTEMA TODAY 38 SMALL SCHOOL, TO READ THE PROGRAM! José Antonio Abreu’s BIG EFFORT, Instructing students in Pop music connects creation has taken GREAT SUCCESS the art and techniques instantly with many root in the U.S. and Alexandria Hanessian’s of sight-singing can reap students. How can continues to grow small but mighty middle many rewards in your music educators use through programs such school program thrives choral rehearsals and it in their classrooms as the Corona Youth in Spencertown, beyond. to increase student Music Project and New York. engagement? Juneau Alaska Music Matters. Photo by Little Kids Rock. Photo by nafme.org 1 October 2015 Volume 23, Number 2 Student composers contents (far left and right) work with teachers Conductor Marin Alsop 56 at Williamsville East works with students in High School. -

The Challenge of African Art Music Le Défi De La Musique Savante Africaine Kofi Agawu

Document generated on 09/27/2021 1:07 p.m. Circuit Musiques contemporaines The Challenge of African Art Music Le défi de la musique savante africaine Kofi Agawu Musiciens sans frontières Article abstract Volume 21, Number 2, 2011 This essay offers broad reflection on some of the challenges faced by African composers of art music. The specific point of departure is the publication of a URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1005272ar new anthology, Piano Music of Africa and the African Diaspora, edited by DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1005272ar Ghanaian pianist and scholar William Chapman Nyaho and published in 2009 by Oxford University Press. The anthology exemplifies a diverse range of See table of contents creative achievement in a genre that is less often associated with Africa than urban ‘popular’ music or ‘traditional’ music of pre-colonial origins. Noting the virtues of musical knowledge gained through individual composition rather than ethnography, the article first comments on the significance of the Publisher(s) encounters of Steve Reich and György Ligeti with various African repertories. Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal Then, turning directly to selected pieces from the anthology, attention is given to the multiple heritage of the African composer and how this affects his or her choices of pitch, rhythm and phrase structure. Excerpts from works by Nketia, ISSN Uzoigwe, Euba, Labi and Osman serve as illustration. 1183-1693 (print) 1488-9692 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Agawu, K. (2011). The Challenge of African Art Music. Circuit, 21(2), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.7202/1005272ar Tous droits réservés © Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 2011 This document is protected by copyright law. -

Form in the Music of John Adams

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Ridderbusch, Michael, "Form in the Music of John Adams" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6503. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6503 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch DMA Research Paper submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Theory and Composition Andrew Kohn, Ph.D., Chair Travis D. Stimeling, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Cynthia Anderson, MM Matthew Heap, Ph.D. School of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2017 Keywords: John Adams, Minimalism, Phrygian Gates, Century Rolls, Son of Chamber Symphony, Formalism, Disunity, Moment Form, Block Form Copyright ©2017 by Michael Ridderbusch ABSTRACT Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch The American composer John Adams, born in 1947, has composed a large body of work that has attracted the attention of many performers and legions of listeners. -

An Examination of Minimalist Tendencies in Two Early Works by Terry Riley Ann Glazer Niren Indiana University Southeast First I

An Examination of Minimalist Tendencies in Two Early Works by Terry Riley Ann Glazer Niren Indiana University Southeast First International Conference on Music and Minimalism University of Wales, Bangor Friday, August 31, 2007 Minimalism is perhaps one of the most misunderstood musical movements of the latter half of the twentieth century. Even among musicians, there is considerable disagreement as to the meaning of the term “minimalism” and which pieces should be categorized under this broad heading.1 Furthermore, minimalism is often referenced using negative terminology such as “trance music” or “stuck-needle music.” Yet, its impact cannot be overstated, influencing both composers of art and rock music. Within the original group of minimalists, consisting of La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass2, the latter two have received considerable attention and many of their works are widely known, even to non-musicians. However, Terry Riley is one of the most innovative members of this auspicious group, and yet, he has not always received the appropriate recognition that he deserves. Most musicians familiar with twentieth century music realize that he is the composer of In C, a work widely considered to be the piece that actually launched the minimalist movement. But is it really his first minimalist work? Two pieces that Riley wrote early in his career as a graduate student at Berkeley warrant closer attention. Riley composed his String Quartet in 1960 and the String Trio the following year. These two works are virtually unknown today, but they exhibit some interesting minimalist tendencies and indeed foreshadow some of Riley’s later developments. -

Minimalism Post-Modernism Is a Term That Refers to Events After the So

Post-Modernism - Minimalism Post-Modernism is a term that refers to events after the so-called Modern period. The term suggests that we are now using what we learned in the “modern” period, but mixing it with ideas from the more distant past. A major movement within Post-Modernism is Minimalism Minimalism mixes some Eastern philosophical principles involving chant and meditation with simple tonal materials. Basic definition of Minimalism: sustained or repetitive use of simple (often tonal) materials. The movement began with LaMonte Young (b.1935); he used simple textures and consonant materials; often called trance music. Terry Riley (b.1935) is credited with first minimalist work In C (1964). The piece has repeated high C’s on piano maintaining simple pulse. Score has 53 short motives to be played by a group any size; players play all 53 figures, repeating as many times and as frequently as desired. Performance ends when all players are done with all 53 figures. Because figures change in content, there is subtle but constantly shifting texture all the time. Steve Reich (b. 1936) prefers to call his music “Structural” not minimal. His music is influenced by his study of African drumming. Some of his early works use phasing, where a tape loop is set up: the tape records first sounds made by performer; then plays them back while performer continues to play. More layers are added, and gradually live sounds get ahead of play-back. Effect can be hypnotic: trance-like. Violin Phase (1967) is example. In Mid-70’s Reich expanded his viewpoint and his ensemble: Music for 18 Musicians is a little like In C, but there is much more variation in patterns. -

A Critical Evaluation of the Nature of Music Education in the Public Schools of British Columbia

A CRITICAL EVALUATION OF THE NATURE OF MUSIC EDUCATION IN THE PUBLIC SCHOOLS OF BRITISH COLUMBIA David James Phyall Associate in Arts and Science (Music), Capilano College, 1982 B.A., SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY, 1989 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Faculty of Education @ David James Phyall 1993 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY March 1993 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: David James P hyall Degree: Master of Arts Title of Project: A Critical Evaluation of the Nature of Music Education in the Public Schools of British Columbia Examining Committee: Chair: Anne Corbishley Robert Walker Senior Supervisor Owen Underhill Associate Professor School for the Contemporary Arts - Allan ~lin&an Professor Music Department, UBC Allan MacKinnon Assistant Professor Faculty of Education Simon Fraser University External Examiner Date Approved: 2 b7 3/73 Partial Copyright License I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

“Classical” Minimalism

from Richard Taruskin, “Oxford History of Western Music Volume V: Music in the Late Twentieth Century; Chapter 8: A Harmonious Avant-Garde?”. Retrieved 4/29/2011 from oxfordwesternmusic.com. “CLASSICAL” MINIMALISM For many listeners, the most characteristic and style-defining aspect of In C is the constant audible eighth-note pulse that underlies and coordinates all of the looping, and that seems, because it provides a constant pedal of Cs, to be fundamentally bound up with the work's concept. Like much modernist practice since at least Stravinsky, it puts the rhythmic spotlight on the “subtactile” level, accommodating and facilitating the free metamorphosis of the felt beat —for example, from quarters to dotted quarters at the twenty-second module of In C—and allows their multiple presence to be felt as levels within a complex texture. It may be surprising, therefore, to learn that the constant C-pulse was an afterthought, adopted in rehearsal for what seemed at the time a purely utilitarian purpose (simply to keep the group together in lieu of a conductor), and that it was not even Riley's idea. It was Reich's. Steve Reich came from a background very different from Young's and Riley's. Where they had a rural, working-class upbringing on the West Coast, Reich was born into a wealthy, professional- class family in cosmopolitan New York. Like most children of his economic class, Reich had traditional piano lessons and plenty of exposure to what in later years he mildly derided as the “bourgeois classics.” He had an elite education culminating in a Cornell baccalaureate with a major in philosophy. -

Structural Analysis and Segmentation of Music Signals

STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS AND SEGMENTATION OF MUSIC SIGNALS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF TECHNOLOGY OF THE UNIVERSITAT POMPEU FABRA FOR THE PROGRAM IN COMPUTER SCIENCE AND DIGITAL COMMUNICATION IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF - DOCTOR PER LA UNIVERSITAT POMPEU FABRA Bee Suan Ong 2006 © Copyright by Bee Suan Ong 2006 All Rights Reserved ii Dipòsit legal: B.5219-2008 ISBN: 978-84-691-1756-9 DOCTORAL DISSERTATION DIRECTION Dr. Xavier Serra Department of Technology Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona This research was performed at theMusic Technology Group of the Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona, Spain. Primary support was provided by the EU projects FP6-507142 SIMAC http://www.semanticaudio.org. iii Abstract Automatic audio content analysis is a general research area in which algorithms are developed to allow computer systems to understand the content of digital audio signals for further exploitation. Automatic music structural analysis is a specific subset of audio content analysis with its main task to discover the structure of music by analyzing audio signals to facilitate better handling of the current explosively expanding amounts of audio data available in digital collections. In this dissertation, we focus our investigation on four areas that are part of audio-based music structural analysis. First, we propose a unique framework and method for temporal audio segmentation at the semantic level. The system aims to detect structural changes in music to provide a way of separating the different “sections” of a piece according to their structural titles (i.e. intro, verse, chorus, bridge). We present a two-phase music segmentation system together with a combined set of low-level audio descriptors to be extracted from music audio signals. -

Clever Children: the Sons and Daughters of Experimental Music?

Clever Children: The Sons and Daughters of Experimental Music Author Carter, David Published 2009 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Queensland Conservatorium DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/1356 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367632 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Clever Children: The Sons and Daughters of Experimental Music? David Carter B.Music / Music Technology (Honours, First Class) Queensland Conservatorium Griffith University A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy 19 June 2008 Keywords Contemporary Music; Dance Music; Disco; DJ; DJ Spooky; Dub; Eight Lines; Electronica; Electronic Music; Errata Erratum; Experimental Music; Hip Hop; House; IDM; Influence; Techno; John Cage; Minimalism; Music History; Musicology; Rave; Reich Remixed; Scanner; Surface Noise. i Abstract In the late 1990s critics, journalists and music scholars began referring to a loosely associated group of artists within Electronica who, it was claimed, represented a new breed of experimentalism predicated on the work of composers such as John Cage, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Steve Reich. Though anecdotal evidence exists, such claims by, or about, these ‘Clever Children’ have not been adequately substantiated and are indicative of a loss of history in relation to electronic music forms (referred to hereafter as Electronica) in popular culture. With the emergence of the Clever Children there is a pressing need to redress this loss of history through academic scholarship that seeks to document and critically reflect on the rhizomatic developments of Electronica and its place within the history of twentieth century music. -

Terms from Kostka Twentieth Century Music

AnalysisofContemporaryMusic Terminology Dr. Mark Feezell The following list of terms is taken from Kostka’s Materials and Techniques of Twentieth-Century Music, 3rd ed. Most of the definitions are word-for-word from the same text. This is a VERY useful study guide for the text, but does not substitute for careful reading and examination of the examples in the text itself. Ch. Term Pg. Definition 1 chromatic mediant rela- 3 Triads with roots M3 or m3 apart, both major or both minor, one common tone tionship 1 doubly chromatic me- 3 Triads with roots M3 or m3 apart, one major, one minor; no common tones diant relationship 1 direct modulation 3 Modulation with no common chord between the two keys 1 tritone relationships 5 Movement of one harmony directly to a harmony whose root is a tritone away 1 real sequence 6 A sequence in which the pattern is transposed exactly 1 brief tonicizations 6 A quick succession of tonal centers, often associated with real sequences 1 enharmonicism 6 The enharmonic reinterpretation of certain (normally chromatic) harmonies so that they resolve in an unexpected way; ex: Ger+6 --> V7 1 suspended tonality 6 Passages that are tonally ambiguous 1 parallel voice leading 7 A type of progression in which at least some voices move in parallel motion 1 nonfunctional chord 8 A progression in which the chords do not “progress” in any of the ways found in succession diatonic tonal harmony 1 voice-leading chords 9 Chords that are the result of goal-directed motion in the various voices rather than traditional harmonic progression 1 unresolved dissonances 10 Dissonances which do not follow the dictates of functional harmony to resolve. -

Metrical Issues in John Adams's <I>Short Ride in a Fast Machine</I>

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications: School of Music Music, School of 2001 Metrical Issues in John Adams's Short Ride in a Fast Machine Stanley V. Kleppinger University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub Part of the Music Theory Commons Kleppinger, Stanley V., "Metrical Issues in John Adams's Short Ride in a Fast Machine" (2001). Faculty Publications: School of Music. 52. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub/52 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications: School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. From Indiana Theory Review Volume 22, no. 1 (2001, appeared in 2003) Metrical Issues ill John Adams's Short Ride in a Fast Machine Stanley V. Kleppinger T IS HARD TO IMAGINE a musical surface that strikes the listener with more metrical conflict than that of John Adams's Short Ride in a Fast Machine (1986). I According to the composer, this orchestral fanfare is inspired by the experi ence of speeding down a highway in a too-fast sports car. As he explained in an interview: The image that I had while composing this piece was a ride that I once took in a sport car. A relative of mine had bought a Ferrari, and he asked me late one night to take a ride in it, and we went out onto the highway, and I wished I hadn't [laughs].