Proposal for Inclusion of Five Vulture Species Occuring in Sub-Saharan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vulture Msap)

MULTI-SPECIES ACTION PLAN TO CONSERVE AFRICAN-EURASIAN VULTURES (VULTURE MSAP) CMS Raptors MOU Technical Publication No. 5 CMS Technical Series No. xx MULTI-SPECIES ACTION PLAN TO CONSERVE AFRICAN-EURASIAN VULTURES (VULTURE MSAP) CMS Raptors MOU Technical Publication No. 5 CMS Technical Series No. xx Overall project management Nick P. Williams, CMS Raptors MOU Head of the Coordinating Unit [email protected] Jenny Renell, CMS Raptors MOU Associate Programme Officer [email protected] Compiled by André Botha, Endangered Wildlife Trust Overarching Coordinator: Multi-species Action Plan to conserve African-Eurasian Vultures [email protected] Jovan Andevski, Vulture Conservation Foundation European Regional Coordinator: Multi-species Action Plan to conserve African-Eurasian Vultures [email protected] Chris Bowden, Royal Society for the Protection of Birds Asian Regional Coordinator: Multi-species Action Plan to conserve African-Eurasian Vultures [email protected] Masumi Gudka, BirdLife International African Regional Coordinator: Multi-species Action Plan to conserve African-Eurasian Vultures [email protected] Roger Safford, BirdLife International Senior Programme Manager: Preventing Extinctions [email protected] Nick P. Williams, CMS Raptors MOU Head of the Coordinating Unit [email protected] Technical support Roger Safford, BirdLife International José Tavares, Vulture Conservation Foundation Regional Workshop Facilitators Africa - Chris Bowden, Royal Society for the Protection of Birds Europe – Boris Barov, BirdLife International Asia and Middle East - José Tavares, Vulture Conservation Foundation Overarching Workshop Chair Fernando Spina, Chair of the CMS Scientific Council Design and layout Tris Allinson, BirdLife International 2 Multi-species Action Plan to Conserve African-Eurasian Vultures (Vulture MsAP) Contributors Lists of participants at the five workshops and of other contributors can be found in Annex 1. -

State of Africa's Birds

An assessment by the BirdLife Africa Partnership1 State of Africa’s birds INTRODUCTION: The importance of birds and biodiversity Biodiversity Foreword underpins In 2009, BirdLife Botswana, the BirdLife Partner in Botswana, working with the Government of Botswana, established a Bird Population Monitoring (BPM) Programme. The BPM Programme is part of our lives the global Wild Bird Index effort, which uses information on birds to assess the overall condition of ecosystems and the environment on which we all depend. These trends will be used to set Africa is rich in its variety of conservation priorities, report on biodiversity changes (including the response of fauna and flora to living things, together referred climate change), as well as serve as useful inputs to State Of the Environment Reports and national to as biodiversity. Biodiversity reports to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). is fundamental to human wellbeing: it offers multiple Currently there are over 350 volunteers supporting the programme who regularly monitor 241 transects spread throughout the country. My Government has been particularly supportive of the BPM opportunities for development Programme because it, among other things, bolsters the participation of rural communities in natural and improving livelihoods. resources management. Additionally, analysis of bird data will influence environmental policies and It is the basis for essential their implementation (e.g. game bird hunting quotas, and the control of the Red-billed Quelea), environmental services upon land-use planning and tourism development. The science of using bird information by the BirdLife which life on earth depends. Global Partnership to inform policies has far reaching impacts from local to global level. -

Namibia & the Okavango

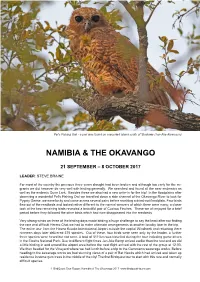

Pel’s Fishing Owl - a pair was found on a wooded island south of Shakawe (Jan-Ake Alvarsson) NAMIBIA & THE OKAVANGO 21 SEPTEMBER – 8 OCTOBER 2017 LEADER: STEVE BRAINE For most of the country the previous three years drought had been broken and although too early for the mi- grants we did however do very well with birding generally. We searched and found all the near endemics as well as the endemic Dune Lark. Besides these we also had a new write-in for the trip! In the floodplains after observing a wonderful Pel’s Fishing Owl we travelled down a side channel of the Okavango River to look for Pygmy Geese, we were lucky and came across several pairs before reaching a dried-out floodplain. Four birds flew out of the reedbeds and looked rather different to the normal weavers of which there were many, a closer look at the two remaining birds revealed a beautiful pair of Cuckoo Finches. These we all enjoyed for a brief period before they followed the other birds which had now disappeared into the reedbeds. Very strong winds on three of the birding days made birding a huge challenge to say the least after not finding the rare and difficult Herero Chat we had to make alternate arrangements at another locality later in the trip. The entire tour from the Hosea Kutako International Airport outside the capital Windhoek and returning there nineteen days later delivered 375 species. Out of these, four birds were seen only by the leader, a further three species were heard but not seen. -

The Decline of an Urban Hooded Vulture Necrosyrtes Monachus Population in Dakar, Senegal, Over 50 Years

Ostrich Journal of African Ornithology ISSN: 0030-6525 (Print) 1727-947X (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tost20 The decline of an urban Hooded Vulture Necrosyrtes monachus population in Dakar, Senegal, over 50 years Wim C Mullié, François-Xavier Couzi, Moussa Sega Diop, Bram Piot, Theo Peters, Pierre A Reynaud & Jean-Marc Thiollay To cite this article: Wim C Mullié, François-Xavier Couzi, Moussa Sega Diop, Bram Piot, Theo Peters, Pierre A Reynaud & Jean-Marc Thiollay (2017) The decline of an urban Hooded Vulture Necrosyrtes monachus population in Dakar, Senegal, over 50 years, Ostrich, 88:2, 131-138, DOI: 10.2989/00306525.2017.1333538 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.2989/00306525.2017.1333538 View supplementary material Published online: 20 Jul 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 11 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tost20 Download by: [2.83.93.12] Date: 17 August 2017, At: 00:02 Ostrich 2017, 88(2): 131–138 Copyright © NISC (Pty) Ltd Printed in South Africa — All rights reserved OSTRICH ISSN 0030–6525 EISSN 1727-947X http://dx.doi.org/10.2989/00306525.2017.1333538 The decline of an urban Hooded Vulture Necrosyrtes monachus population in Dakar, Senegal, over 50 years§ Wim C Mullié1*, François-Xavier Couzi2, Moussa Sega Diop3, Bram Piot4, Theo Peters5, Pierre A Reynaud6 and Jean-Marc Thiollay7 1 BP 45590, 10700 Dakar-Fann, Senegal 2 Société d’Etudes Ornithologiques de la Réunion, Saint André, Île de la Réunion, France 3 AfriWet Consultants, Dakar-Thiaroye, Senegal 4 Cité Ndiatte Almadies, Ngor, Dakar, Senegal 5 Royal Netherlands Embassy, Dakar, Senegal 6 275 Rue Robert Schuman, 83000 Toulon, France 7 2 Rue de la Rivière, 10220 Rouilly Sacey, France * Corresponding author, email: [email protected] As in many West African cities, in Dakar Hooded Vultures Necrosyrtes monachus have always been characteristic urban scavengers. -

2017 Namibia, Botswana & Victoria Falls Species List

Eagle-Eye Tours Namibia, Okavango and Victoria Falls November 2017 Bird List Status: NT = Near-threatened, VU = Vulnerable, EN = Endangered, CR = Critically Endangered Common Name Scientific Name Trip STRUTHIONIFORMES Ostriches Struthionidae Common Ostrich Struthio camelus 1 ANSERIFORMES Ducks, Geese and Swans Anatidae White-faced Whistling Duck Dendrocygna viduata 1 Spur-winged Goose Plectropterus gambensis 1 Knob-billed Duck Sarkidiornis melanotos 1 Egyptian Goose Alopochen aegyptiaca 1 African Pygmy Goose Nettapus auritus 1 Hottentot Teal Spatula hottentota 1 Cape Teal Anas capensis 1 Red-billed Teal Anas erythrorhyncha 1 GALLIFORMES Guineafowl Numididae Helmeted Guineafowl Numida meleagris 1 Pheasants and allies Phasianidae Crested Francolin Dendroperdix sephaena 1 Hartlaub's Spurfowl Pternistis hartlaubi H Red-billed Spurfowl Pternistis adspersus 1 Red-necked Spurfowl Pternistis afer 1 Swainson's Spurfowl Pternistis swainsonii 1 Natal Spurfowl Pternistis natalensis 1 PODICIPEDIFORMES Grebes Podicipedidae Little Grebe Tachybaptus ruficollis 1 Black-necked Grebe Podiceps nigricollis 1 PHOENICOPTERIFORMES Flamingos Phoenicopteridae Greater Flamingo Phoenicopterus roseus 1 Lesser Flamingo - NT Phoeniconaias minor 1 CICONIIFORMES Storks Ciconiidae Yellow-billed Stork Mycteria ibis 1 Eagle-Eye Tours African Openbill Anastomus lamelligerus 1 Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia episcopus 1 Marabou Stork Leptoptilos crumenifer 1 PELECANIFORMES Ibises, Spoonbills Threskiornithidae African Sacred Ibis Threskiornis aethiopicus 1 Hadada Ibis Bostrychia -

Recent Literature and Book Reviews

Vulture News 69 November 2015 RECENT LITERATURE AND BOOK REVIEWS P.J. Mundy BAMFORD, A. J., MONADJEM, A., DIEKMANN, M. & HARDY, I. C.W. (2009). Development of non-explosive-based methods for mass capture of vultures. South African Journal of Wildlife Research 39: 202-208. Investigated methods of launching nets, powered by black powder, detonators, elastic, and compressed air, and a walk-in trap. The last proved most effective at capturing birds, needed no licence, but took a long time to construct and of course was barely portable. (email for Monadjem: [email protected]) BIRD, J. P. & BLACKBURN, T. M. (2011). Observations of large raptors in northeast Sudan. Scopus 31: 19-27. From a 430km transect (Atbara to Port Sudan) and other ad hoc observations, in January 2010, three species of vulture were seen. Thirty Egyptian Vultures on the transect, counts of 21 and 24 Lappet-faced Vultures at a carcass and one Hooded Vulture, were noted. (email: [email protected]) BREWSTER, C. A & TYLER, S. J. (2012). Summary of category B records. Babbler 57: 45-47. Many sightings are listed for the Cape, Lappet-faced, White-headed and Hooded Vultures, but no ages. In the Tswapong Hills, no nests of the Cape Vulture were seen at Lerala, but 76 were seen at Moremi Gorge. On p. 57 many sightings are listed of the White-backed Vulture, from singles up to groups of about 70. c ( /o BLB, Box 26691, Gaborone) 51 Vulture News 69 November 2015 BRUCE-MILLER, I. (2008). Martial Eagle Polemaetus bellicosus apparently killing White-headed Vulture Trigonoceps occipitalis. -

Trade of Threatened Vultures and Other Raptors for Fetish and Bushmeat in West and Central Africa

Trade of threatened vultures and other raptors for fetish and bushmeat in West and Central Africa R. BUIJ,G.NIKOLAUS,R.WHYTOCK,D.J.INGRAM and D . O GADA Abstract Diurnal raptors have declined significantly in Introduction western Africa since the s. To evaluate the impact of traditional medicine and bushmeat trade on raptors, we ex- ildlife is exploited throughout West and Central amined carcasses offered at markets at sites (– stands WAfrica (Martin, ). The trade in bushmeat (wild- per site) in countries in western Africa during –. sourced meat) has been recognized as having a negative im- Black kite Milvus migrans andhoodedvultureNecrosyrtes pact on wildlife populations in forests and savannahs monachus together accounted for %of, carcasses com- (Njiforti, ; Fa et al., ; Lindsey et al., ), and it . prising species. Twenty-seven percent of carcasses were of is estimated billion kg of wild animal meat is traded an- species categorized as Near Threatened, Vulnerable or nually in Central Africa (Wilkie & Carpenter, ). In add- Endangered on the IUCN Red List. Common species were ition to being exploited for bushmeat, many animals are traded more frequently than rarer species, as were species hunted and traded specifically for use in traditional medi- with frequent scavenging behaviour (vs non-scavenging), gen- cine, also known as wudu, juju or fetish (Adeola, ). eralist or savannah habitat use (vs forest), and an Afrotropical The use of wildlife items for the treatment of a range of (vs Palearctic) breeding range. Large Afrotropical vultures physical and mental diseases, or to bring good fortune, were recorded in the highest absolute and relative numbers has been reported in almost every country in West and in Nigeria, whereas in Central Africa, palm-nut vultures Central Africa. -

Function and Occurrence of Facial Flushing in Birds

Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, Part A 143 (2006) 78–84 www.elsevier.com/locate/cbpa Function and occurrence of facial flushing in birds Juan José Negro a,⁎, José Hernán Sarasola a, Fernando Fariñas b, Irene Zorrilla b a Department of Applied Biology, Estación Biológica de Doñana, CSIC, Avda. de María Luisa s/n, Pabellón del Perú, 41013 Sevilla, Spain b Instituto Andaluz de Patología y Microbiología-IAMA, C/Domingo Lozano 60-62, 29010 Málaga, Spain Received 1 June 2005; received in revised form 21 October 2005; accepted 22 October 2005 Available online 5 December 2005 Abstract So far overlooked as a pigment involved in visual communication, the haemoglobin contained in the blood of all birds is responsible for the red flushing colours in bare skin areas of some species. Our aim has been twofold: (1) to study sub-epidermical adaptations for blood circulation in two flushing species: the crested caracara (Polyborus plancus) and the hooded vulture (Necrosyrtes monachus), and (2) to provide the first compilation of avian species with flushing skin. The bare facial skin of both the caracara and the hooded vulture contains a highly vascularised tissue under the epidermis that may be filled with blood and would thus produce red skin colours. In contrast, feathered areas of the head show very few vessels immersed in connective tissue and have no potential for colour changes. Species with flushing colours are few but phylogenetically diverse, as they belong to 12 different avian orders and at least 20 families. The majority are dark-coloured, large-sized species living in hot environments that may have originally evolved highly vascularised skin patches for thermoregulation. -

Raptors in the East African Tropics and Western Indian Ocean Islands: State of Ecological Knowledge and Conservation Status

j. RaptorRes. 32(1):28-39 ¸ 1998 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. RAPTORS IN THE EAST AFRICAN TROPICS AND WESTERN INDIAN OCEAN ISLANDS: STATE OF ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE AND CONSERVATION STATUS MUNIR VIRANI 1 AND RICHARD T. WATSON ThePeregrine Fund, Inc., 566 WestFlying Hawk Lane, Boise,1D 83709 U.S.A. ABSTRACT.--Fromour reviewof articlespublished on diurnal and nocturnal birds of prey occurringin Africa and the western Indian Ocean islands,we found most of the information on their breeding biology comesfrom subtropicalsouthern Africa. The number of published papers from the eastAfrican tropics declined after 1980 while those from subtropicalsouthern Africa increased.Based on our KnoM- edge Rating Scale (KRS), only 6.3% of breeding raptorsin the eastAfrican tropicsand 13.6% of the raptorsof the Indian Ocean islandscan be consideredWell Known,while the majority,60.8% in main- land east Africa and 72.7% in the Indian Ocean islands, are rated Unknown. Human-caused habitat alteration resultingfrom overgrazingby livestockand impactsof cultivationare the main threatsfacing raptors in the east African tropics, while clearing of foreststhrough slash-and-burnmethods is most important in the Indian Ocean islands.We describeconservation recommendations, list priorityspecies for study,and list areasof ecologicalunderstanding that need to be improved. I•y WORDS: Conservation;east Africa; ecology; western Indian Ocean;islands; priorities; raptors; research. Aves rapacesen los tropicos del este de Africa yen islasal oeste del Oc•ano Indico: estado del cono- cimiento eco16gicoy de su conservacitn RESUMEN.--Denuestra recopilacitn de articulospublicados sobre aves rapaces diurnas y nocturnasque se encuentran en Africa yen las islasal oeste del Octano Indico, encontramosque la mayoriade la informaci6n sobre aves rapacesresidentes se origina en la regi6n subtropical del sur de Africa. -

ZSL National Red List of Nepal's Birds Volume 5

The Status of Nepal's Birds: The National Red List Series Volume 5 Published by: The Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, UK Copyright: ©Zoological Society of London and Contributors 2016. All Rights reserved. The use and reproduction of any part of this publication is welcomed for non-commercial purposes only, provided that the source is acknowledged. ISBN: 978-0-900881-75-6 Citation: Inskipp C., Baral H. S., Phuyal S., Bhatt T. R., Khatiwada M., Inskipp, T, Khatiwada A., Gurung S., Singh P. B., Murray L., Poudyal L. and Amin R. (2016) The status of Nepal's Birds: The national red list series. Zoological Society of London, UK. Keywords: Nepal, biodiversity, threatened species, conservation, birds, Red List. Front Cover Back Cover Otus bakkamoena Aceros nipalensis A pair of Collared Scops Owls; owls are A pair of Rufous-necked Hornbills; species highly threatened especially by persecution Hodgson first described for science Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson and sadly now extinct in Nepal. Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of participating organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of any participating organizations. Notes on front and back cover design: The watercolours reproduced on the covers and within this book are taken from the notebooks of Brian Houghton Hodgson (1800-1894). -

NOTES on the BREEDING CYCLE of CAPE VULTURES &Lpar

RAPTOR RESEARCH A QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE RAPTOR RESEARCH FOUNDATION, INC. Voi. 20 SVMMER 1986 NO. 2 NOTES ON THE BREEDING CYCLE OF CAPE VULTURES (Gypscoprotheres) ALISTAIR S. ROBERTSON ABSTRACT- Observationswere made of the pre-laying,incubation and nestlingperiods of the CapeVulture (Gyps coprotheres)at a colonyin thesouthwestern Cape Province, South Africa. Some members of thecolony were colour-ringed as nestlings;this allowedthe sex of breedingpartners to be determinedby subsequentobservation of copulation. Informationon occupancyof nestsites, nest-building, a sex-related behavioural difference, dates of egg-laying,incuba- tion and nestlingperiods, parasite infestation (Prosimuliium spp.), and associatedblood parasites(Leucocytozoon) of nestlingsis presented. The Cape Vulture (Gypscoprotheres) isthe heaviest All activenest sitesand roostingledges were visiblefrom the endemic accipitrid in southern Africa and is the southeastside of the ravine,300-400 m away.Observations were madewith binoculars and a 15-60xtelescope. Observations began only vulture in the region t(; breedin colonieson in May 1981,continued for 12 d eachmonth regardless of weather cliff faces (Mundy 1982). Approximately 3500 conditions,and ended in May 1982.One "day"represents the time Cape Vulture nestlingshave been colour-ringed period 0730 H - 1630 H. The concludingstages of the 1980 (banded) in southern Africa since 1974; studies of breedingseason, all stagesof the 1981season and the initiationof the 1982 season were covered. Presence of birds at sites and -

Visual Field Shape and Foraging Ecology in Diurnal Raptors

Visual field shape and foraging ecology in diurnal raptors Simon Potier, Olivier Duriez, Gregory Cunningham, Vincent Bonhomme, Colleen O’Rourke, Esteban Fernández-Juricic, Francesco Bonadonna To cite this version: Simon Potier, Olivier Duriez, Gregory Cunningham, Vincent Bonhomme, Colleen O’Rourke, et al.. Visual field shape and foraging ecology in diurnal raptors. Journal of Experimental Biology, Cambridge University Press, 2018, 221 (14), pp.jeb177295. 10.1242/jeb.177295. hal-03132841 HAL Id: hal-03132841 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03132841 Submitted on 5 Feb 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. © 2018. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2018) 221, jeb177295. doi:10.1242/jeb.177295 RESEARCH ARTICLE Visual field shape and foraging ecology in diurnal raptors Simon Potier1,2,*, Olivier Duriez1, Gregory B. Cunningham3, Vincent Bonhomme4, Colleen O’Rourke5, Esteban Fernández-Juricic6 and Francesco Bonadonna1 ABSTRACT separate niches (Safi and Siemers, 2010). Interspecific differences Birds, particularly raptors, are believed to forage primarily using visual in the visual capacities of birds (Fernández-Juricic, 2012; Jones cues. However, raptor foraging tactics are highly diverse – from et al., 2007; Martin, 2014; Moore et al., 2016; Rochon-Duvigneaud, chasing mobile prey to scavenging – which may reflect adaptations of 1943; Walls, 1942) also allow species to respond differently to the their visual systems.