JOSEPH BARRELL I869-1919

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proceedings Op the Twenty-Third Annual Meeting Op the Geological Society Op America, Held at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, December 21, 28, and 29, 1910

BULLETIN OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA VOL. 22, PP. 1-84, PLS. 1-6 M/SRCH 31, 1911 PROCEEDINGS OP THE TWENTY-THIRD ANNUAL MEETING OP THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OP AMERICA, HELD AT PITTSBURGH, PENNSYLVANIA, DECEMBER 21, 28, AND 29, 1910. Edmund Otis Hovey, Secretary CONTENTS Page Session of Tuesday, December 27............................................................................. 2 Election of Auditing Committee....................................................................... 2 Election of officers................................................................................................ 2 Election of Fellows................................................................................................ 3 Election of Correspondents................................................................................. 3 Memoir of J. C. Ii. Laflamme (with bibliography) ; by John M. Clarke. 4 Memoir of William Harmon Niles; by George H. Barton....................... 8 Memoir of David Pearce Penhallow (with bibliography) ; by Alfred E. Barlow..................................................................................................................... 15 Memoir of William George Tight (with bibliography) ; by J. A. Bownocker.............................................................................................................. 19 Memoir of Robert Parr Whitfield (with bibliography by L. Hussa- kof) ; by John M. Clarke............................................................................... 22 Memoir of Thomas -

A History of Connecticut's Long Island Sound Boundary

The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law CUA Law Scholarship Repository Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions Faculty Scholarship 1972 A History of Connecticut's Long Island Sound Boundary Raymond B. Marcin The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/scholar Part of the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Raymond B. Marcin, A History of Connecticut's Long Island Sound Boundary, 46 CONN. B.J. 506 (1972). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions by an authorized administrator of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 506 CONNECTICUT BAR JOURNAL [Vol. 46 A HISTORY OF CONNECTICUT'S LONG ISLAND SOUND BOUNDARY By RAYMOND B. MARciN* THE SCENEt Long before remembered time, ice fields blanketed central India, discharging floes into a sea covering the Plains of Punjab. The Argentine Pampas lay frozen and still beneath a crush of ice. Ice sheets were carving their presence into the highest mountains of Hawaii and New Guinea. On the western land mass, ice gutted what was, in pre-glacial time, a stream valley near the northeastern shore. In this alien epoch, when woolly mammoth and caribou roamed the North American tundra, the ice began to melt. Receding glaciers left an inland lake where the primeval stream valley had been. For a time the waters of the lake reposed in bo- real calm, until, with the melting of the polar cap, the level of the great salt ocean rose to the level of the lake. -

PDF— Granite-Greenstone Belts Separated by Porcupine-Destor

C G E S NT N A ER S e B EC w o TIO ok N Vol. 8, No. 10 October 1998 es st t or INSIDE Rel e • 1999 Section Meetings ea GSA TODAY Rocky Mountain, p. 25 ses North-Central, p. 27 A Publication of the Geological Society of America • Honorary Fellows, p. 8 Lithoprobe Leads to New Perspectives on 70˚ -140˚ 70˚ Continental Evolution -40˚ Ron M. Clowes, Lithoprobe, University -120˚ of British Columbia, 6339 Stores Road, -60˚ -100˚ -80˚ Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4, Canada, 60˚ Wopmay 60˚ [email protected] Slave SNORCLE Fred A. Cook, Department of Geology & Thelon Rae Geophysics, University of Calgary, Calgary, Nain Province AB T2N 1N4, Canada 50˚ ECSOOT John N. Ludden, Centre de Recherches Hearne Pétrographiques et Géochimiques, Taltson Vandoeuvre-les-Nancy, Cedex, France AB Trans-Hudson Orogen SC THOT LE WS Superior Province ABSTRACT Cordillera AG Lithoprobe, Canada’s national earth KSZ o MRS 40 40 science research project, was established o Grenville Province in 1984 to develop a comprehensive Wyoming Penokean GL -60˚ understanding of the evolution of the -120˚ Yavapai Province Orogen Appalachians northern North American continent. With rocks representing 4 b.y. of Earth -100˚ -80˚ history, the Canadian landmass and off- Phanerozoic Proterozoic Archean shore margins provide an exceptional 200 Ma - present 1100 Ma 3200 - 2650 Ma opportunity to gain new perspectives on continental evolution. Lithoprobe’s 470 - 275 Ma 1300 - 1000 Ma 3400 - 2600 Ma 10 study areas span the country and 1800 - 1600 Ma 3800 - 2800 Ma geological time. A pan-Lithoprobe syn- 1900 - 1800 Ma 4000 - 2500 Ma thesis will bring the project to a formal conclusion in 2003. -

Proceedings Op the Eighth Annual Meeting of the Paleontological Society, Held at Albany, New Yoke, December 27, 28, and 29, 1916

Downloaded from gsabulletin.gsapubs.org on August 7, 2015 BULLETIN OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA VOL. 28, PP. 189-234 MARCH 31, 1917 PROCEEDINGS OF THE PALEONTOLOGICAL SOCIETY PROCEEDINGS OP THE EIGHTH ANNUAL MEETING OF THE PALEONTOLOGICAL SOCIETY, HELD AT ALBANY, NEW YOKE, DECEMBER 27, 28, AND 29, 1916. R. S. B a ssle k , Secretary CONTENTS. Page Session of Wednesday, December 27...................................................................... 192 Report of the Council........................................................................................ 192 Secretary’s report ...................................................... ................................ 193 Treasurer’s report ........................................ .............................................. 194 Appointment of Auditing Committee*............................................................. 195 Election of officers and members.................................................................... 195 Presentation of general papers on vertebrate paleontology...................... 196 Pliocene mammalian faunas of North America [abstract]; by John C. M erriam...................................................................................... 196 Later Tertiary formations of western Nebraska; by W. D. Mat thew ............................................................................................................ 197 Geologic tour of western Nebraska; by H. F. Osborn...................... 197 The pulse of life; by R. S. Lull............................................................... -

Bedrock Valleys of the New England Coast As Related to Fluctuations of Sea Level

Bedrock Valleys of the New England Coast as Related to Fluctuations of Sea Level By JOSEPH E. UPSON and CHARLES W. SPENCER SHORTER CONTRIBUTIONS TO GENERAL GEOLOGY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 454-M Depths to bedrock in coastal valleys of New England, and nature of sedimentary Jill resulting from sea-level fluctuations in Pleistocene and Recent time UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1964 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director The U.S. Geological Survey Library has cataloged this publication, as follows: Upson, Joseph Edwin, 1910- Bedrock valleys of the New England coast as related to fluctuations of sea level, by Joseph E. Upson and Charles W. Spencer. Washington, U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1964. iv, 42 p. illus., maps, diagrs., tables. 29 cm. (U.S. Geological Survey. Professional paper 454-M) Shorter contributions to general geology. Bibliography: p. 39-41. (Continued on next card) Upson, Joseph Edwin, 1910- Bedrock valleys of the New England coast as related to fluctuations of sea level. 1964. (Card 2) l.Geology, Stratigraphic Pleistocene. 2.Geology, Stratigraphic Recent. S.Geology New England. I.Spencer, Charles Winthrop, 1930-joint author. ILTitle. (Series) For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 CONTENTS Page Configuration and depth of bedrock valleys, etc. Con. Page Abstract.__________________________________________ Ml Buried valleys of the Boston area. _ _______________ -

M.Y. Williams Fonds

M.Y. Williams fonds Compiled by Christopher Hives (1988) Last revised February 2019 University of British Columbia Archives Table of Contents Fonds Description o Title / Dates of Creation / Physical Description o Biographical Sketch o Scope and Content o Note Series Descriptions o Biographical/Personal Material series o Family History series o Publications series o Field Notebooks/Diaries series o Reports series o Manuscripts / Research Notes series o Correspondence series o Reprint series o Miscellaneous Subjects series o Maps series o Card Indexes series o Miscellaneous Printed/Published Material series o Photographs series File List Catalogue entry (UBC Library catalogue) Fonds Description M.Y. Williams fonds. – 1875-1973. 15.78 m of textual records and published materials. ca. 462 photographs: b&w; 20.5 x 25.5 or smaller. 3 albums. ca. 350 maps. Biographical Sketch From: Okulitch, V.J. "Merton Yarwood Williams (1883-1974)", Royal Society of Canada, Proceedings (Vol. 12, 1974), pp. 84-88: Professor Merton Yarwood Williams Ph.D., D.Sc., died on 3 February 1974 in Vancouver, B.C. in his ninetieth year. With his passing, the University of British Columbia lost one of its original faculty members and the geology profession lost a pioneer in stratigraphic and petroleum exploration in western Canada. "M.Y.," as he was affectionately referred to by colleagues and friends, was born near Bloomfield, Ontario, on 21 June 1883. Both his parents were of Loyalist descent and their ancestors moved to Ontario at the time of the American Revolution. He graduated from Picton High School in 1902 and then taught school for three years before deciding to enter Queen's University at Kingston. -

Bedrock Geologic Map of the New Milford Quadrangle, Litchfield and Fairfield Counties, Connecticut

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Prepared in cooperation with the State of Connecticut, Geological and Natural History Survey BEDROCK GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE NEW MILFORD QUADRANGLE, LITCHFIELD AND FAIRFIELD COUNTIES, CONNECTICUT By Gregory J. Walsh1 Open-File Report 03-487 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards (or with the North American Stratigraphic Code). Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. ______________________________________________________________________________ 1U.S. Geological Survey P.O. Box 628 Montpelier, Vermont 05601 The map and database of this report are available online at: http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2003/of03-487/ USGS Open File Report 03-487 On the cover: Photograph of Lake Candlewood from Hubbell Hill in Sherman. View is to the south. Green Island and Deer Island are visible in the center of the view. The Vaughns Neck peninsula is visible on the left side of the photograph. Bedrock Geologic Map of the New Milford Quadrangle, Litchfield and Fairfield Counties, Connecticut 2 USGS Open File Report 03-487 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 4 STRATIGRAPHY .......................................................................................................................... 6 MESOPROTEROZOIC GNEISS.............................................................................................. -

GEOLOGY and GROUND WATER RESOURCE S of Stutsman County, North Dakota

North Dakota Geological Survey WILSON M. LAIRD, State Geologis t BULLETIN 41 North Dakota State Water Conservation Commission MILO W . HOISVEEN, State Engineer COUNTY GROUND WATER STUDIES 2 GEOLOGY AND GROUND WATER RESOURCE S of Stutsman County, North Dakota Part I - GEOLOG Y By HAROLD A. WINTERS GRAND FORKS, NORTH DAKOTA 1963 This is one of a series of county reports which wil l be published cooperatively by the North Dakota Geological Survey and the North Dakota State Water Conservation Commission in three parts . Part I is concerned with geology, Part II, basic data which includes information on existing well s and test drilling, and Part III which will be a study of hydrology in the county . Parts II and III will be published later and will be distributed a s soon as possible . CONTENTS PAGE ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION 3 Acknowledgments 3 Previous work 5 GEOGRAPHY 5 Topography and drainage 5 Climate 7 Soils and vegetation 9 SUMMARY OF THE PRE-PLEISTOCENE STRATIGRAPHY 9 Precambrian 1 1 Paleozoic 1 1 Mesozoic 1 1 PREGLACIAL SURFICIAL GEOLOGY 12 Niobrara Shale 1 2 Pierre Shale 1 2 Fox Hills Sandstone 1 4 Fox Hills problem 1 4 BEDROCK TOPOGRAPHY 1 4 Bedrock highs 1 5 Intermediate bedrock surface 1 5 Bedrock valleys 1 5 GLACIATION OF' NORTH DAKOTA — A GENERAL STATEMENT 1 7 PLEISTOCENE SEDIMENTS AND THEIR ASSOCIATED LANDFORMS 1 8 Till 1 8 Landforms associated with till 1 8 Glaciofluvial :materials 22 Ice-contact glaciofluvial sediments 2 2 Landforms associated with ice-contact glaciofluvial sediments 2 2 Proglacial fluvial sediments 2 3 Landforms associated with proglacial fluvial sediments 2 3 Lacustrine sediments 2 3 Landforms associated with lacustrine sediments 2 3 Other postglacial sediments 2 4 ANALYSIS OF THE SURFICIAL TILL IN STUTSMAN COUNTY 2 4 Leaching and caliche 24 Oxidation 2 4 Stone counts 2 5 Lignite within till 2 7 Grain-size analyses of till _ 2 8 Till samples from hummocky stagnation moraine 2 8 Till samples from the Millarton, Eldridge, Buchanan and Grace Cit y moraines and their associated landforms _ . -

John Mason Clarke

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIRS VOLUME XII'—SIXTH MEMOIR BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR OF JOHN MASON CLARKE BY CHARLES SCHUCHERT PRESENTED TO THE ACADEMY AT THE ANNUAL MEETING, 1926 JOHN MASON CLARKE BY CHARLES SCIIUCHERT In the death of John Mason Clarke, America loses its most brilliant, eloquent, and productive paleontologist, and the world its greatest authority on Devonian life and time. Author of more than 10,000 printed pages, distributed among about 450 books and papers, of which 300 deal with Geology, his efforts had to do mostly with pure science, and he often lamented, in the coming generation of doers, the lack of an adequate apprecia- tion of wondrous nature as recorded on the tablets of the earth's crust. He was peculiarly the child of his environment; born on Devonian rocks replete with fossils, in a home of high ideals and learning, situated in a state that has long appreciated science, he rose into the grandeur of geologic knowledge that was his. Clarke is survived by his wife, formerly Mrs. Fannie V. Bosler, of Philadelphia; by Noah T. Clarke, a son by his first wife, who was Mrs. Emma Sill (nee Juel), of Albany; by two stepdaughters, Miss Marie Bosler and Mrs. Edith (Sill) Humphrey, and a stepson, Mr. Frank N. Sill. Out of a family of six brothers and sisters, four remain to mourn his going: Miss Clara Mason Clarke, who, with Mr. S. Merrill Clarke, for many years city editor of the New York Sun, is living in the old homestead at Canandaigua ; Rev. Lorenzo Mason Clarke, pastor of the First Presbyterian Church of Brooklyn; and Mr. -

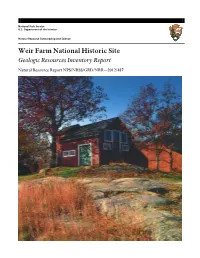

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Weir

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Weir Farm National Historic Site Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR—2012/487 ON THE COVER View of Julian Alden Weir’s studio in Weir Farm National Historic Site. Rock outcrops, such as those in the foreground, are common throughout the park. The bedrock beneath the park is ancient sea floor sediments that were accreted onto North America, hundreds of millions of years ago. They were deformed and metamorphosed during the construction of the Appalachian Mountains. Photograph by Peter Margonelli, courtesy Allison Herrmann (Weir Farm NHS). THIS PAGE The landscape of the park has inspired artists en plein air for more than 125 years. National Park Service photograph available online: http://www.nps.gov/wefa/photosmultimedia/index.htm (accessed 20 January 2012). Weir Farm National Historic Site Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR—2012/487 National Park Service Geologic Resources Division PO Box 25287 Denver, CO 80225 January 2012 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate high-priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. -

Basalts of the Pomperaug Basin, Southwestern Connecticut: Regional, Stratigraphic and Petrologic Features

EARLY MESOZOIC BASALTS OF THE POMPERAUG BASIN, SOUTHWESTERN CONNECTICUT: REGIONAL, STRATIGRAPHIC AND PETROLOGIC FEATURES J. Gregory McHone, Ph.D., C.P.G. Adjunct Professor of Geology University of Connecticut TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary p. 3 Acknowledgments p. 3 Introduction p. 5 Mesozoic Basins p. 5 Field Studies p. 10 Percival, 1842 p. 10 Davis, 1888 p. 10 Hobbs, 1901 p. 12 Meinzer and Sterns, 1929 p. 14 Schutz, 1956 p. 14 Scott, 1974 p. 14 Rodgers, 1985 p. 15 Other work p. 15 Huber, LeTourneau, and McDonald p. 15 South Britain Section p. 16 Southbury Quarry p. 17 Woodbury Quarry p. 19 Orenaug Hills p. 20 Petrography p. 21 Chemistry p. 23 Discussion p. 24 Conclusions p. 24 References and Additional Bibliography p. 25 Plate 1. Geologic Map by Hobbs, 1901 p. 29 Plate II. Geologic Map by Meinzer and Sterns, 1929 (Excerpt) p. 30 Plate III. Geologic Map by Schutz, 1956 p. 31 Plate IV. Geologic Map by Scott, 1974 (Excerpt) p. 32 Plate V. Geologic Map by Rodgers, 1985 (Excerpt) p. 33 Appendix I. Oil well article by Hovey, 1890 p. 34 Appendix II. NEGSA by Hubert and others, 1979 p. 35 Appendix III. NEGSA abstract by Hurtubise and Puffer, 1983 p. 36 Appendix IV. NEGSA abstract by Tolley, 1986 p. 36 Appendix IV. NEGSA abstract by Huber and McDonald, 1992 p. 37 Appendix VI. NEGSA abstract by LeTourneau and Huber, 1997 p. 37 Appendix VII. NEGSA abstract by Blevins-Walker and others, 2001 p. 38 Appendix VIII. NEGSA abstract by LeTourneau, 2002 p. 39 Appendix IX. Table of Chemical Analyses by Philpotts and others, 1996 p. -

GSA TODAY North-Central, P

Vol. 9, No. 10 October 1999 INSIDE • 1999 Honorary Fellows, p. 16 • Awards Nominations, p. 18, 20 • 2000 Section Meetings GSA TODAY North-Central, p. 27 A Publication of the Geological Society of America Rocky Mountain, p. 28 Cordilleran, p. 30 Refining Rodinia: Geologic Evidence for the Australia–Western U.S. connection in the Proterozoic Karl E. Karlstrom, [email protected], Stephen S. Harlan*, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131 Michael L. Williams, Department of Geosciences, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, 01003-5820, [email protected] James McLelland, Department of Geology, Colgate University, Hamilton, NY 13346, [email protected] John W. Geissman, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131, [email protected] Karl-Inge Åhäll, Earth Sciences Centre, Göteborg University, Box 460, SE-405 30 Göteborg, Sweden, [email protected] ABSTRACT BALTICA Prior to the Grenvillian continent- continent collision at about 1.0 Ga, the southern margin of Laurentia was a long-lived convergent margin that SWEAT TRANSSCANDINAVIAN extended from Greenland to southern W. GOTHIAM California. The truncation of these 1.8–1.0 Ga orogenic belts in southwest- ern and northeastern Laurentia suggests KETILIDEAN that they once extended farther. We propose that Australia contains the con- tinuation of these belts to the southwest LABRADORIAN and that Baltica was the continuation to the northeast. The combined orogenic LAURENTIA system was comparable in