Gaining and Maintaining Young People in Wisconsin Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

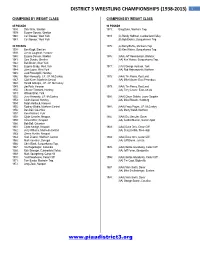

District 3 Wrestling Championships (1938-2013) 1

DISTRICT 3 WRESTLING CHAMPIONSHIPS (1938-2013) 1 CHAMPIONS BY WEIGHT CLASS CHAMPIONS BY WEIGHT CLASS 85 POUNDS 98 POUNDS 1938: Dick Willis, Steelton 1973: Greg Duke, Manheim Twp. 1939: Eugene Donato, Steelton 1940: Carl Bowser, West York 1974: (A) Randy Hoffman, Cumberland Valley 1941: Carl Bowser, West York (B) Bob Enders, Susquehanna Twp. 95 POUNDS 1975: (A) Barry Blefko, Manheim Twp. 1938: Ben Klugh, Steelton (B) Ken Waters, Susquehanna Twp. 1939: James Laughran, Hanover 1940: Eugene Donato, Steelton 1976: (AAA) Jeff Rosenberger, Warwick 1941: Sam Donato, Steelton (AA) Ken Waters, Susquehanna Twp. 1942: Bob Brown, West York 1943: Eugene Brady, West York 1977: (AAA) George Harrison, York 1944: John Loose, West York (AA) Rob Hejmanowski, Northern 1945: Jack Pizzengrilli, Hershey 1946: Merv Hemperly, J.P. J.P. McCaskey 1978: (AAA) Tim Pierce, Red Land 1947: Clair Koser, Manheim Central (AA) Mike Maurer, East Pennsboro 1948: Harold Gillespie, J.P. J.P. McCaskey 1949: Jim Roth, Hanover 1979: (AAA) Tim Pierce, Red Land 1950: Chester Timmons, Hershey (AA) Terry Lauver, East Juniata 1951: William Billet, York 1952: Jerry Hemperly, J.P. McCaskey 1980: (AAA) Chuck Deibler, Lower Dauphin 1953: Cleon Cassel, Hershey (AA) Mike Rhoads, Hamburg 1954: Ralph Hartlaub, Hanover 1955: Rodney Gibble, Manheim Central 1981: (AAA) Fredo Pagan, J.P. McCaskey 1956: Don Bell, Columbia (AA) Marty Walsh, Northern 1957: Ken Weichart, York 1958: Clyde Cressler, Newport 1982: (AAA) Dru Gentzler, Dover 1959: Vance Miller, Newport (AA) Cordell Musser, Garden Spot 1960: Bob Bell, Columbia 1961: Clyde Neidigh, Newport 1983: (AAA) Dave Orris, Cedar Cliff 1962: Jerry Williams, Manheim Central (AA) Craig Corbin, Steel-High 1963: Sherm Hostler, Newport 1964: Stan Zeamer, Manheim Central 1984: (AAA) Dave Orris, Cedar Cliff 1965: Mark Koestner, Donegal (AA) Jeff Brown, Juniata 1966: Chris Black, Susquehanna Twp. -

The Wrestler's Body: Identity and Ideology in North India

The Wrestler’s Body Identity and Ideology in North India Joseph S. Alter UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford © 1992 The Regents of the University of California For my parents Robert Copley Alter Mary Ellen Stewart Alter Preferred Citation: Alter, Joseph S. The Wrestler's Body: Identity and Ideology in North India. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1992 1992. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft6n39p104/ 2 Contents • Note on Translation • Preface • 1. Search and Research • 2. The Akhara: Where Earth Is Turned Into Gold • 3. Gurus and Chelas: The Alchemy of Discipleship • 4. The Patron and the Wrestler • 5. The Discipline of the Wrestler’s Body • 6. Nag Panchami: Snakes, Sex, and Semen • 7. Wrestling Tournaments and the Body’s Recreation • 8. Hanuman: Shakti, Bhakti, and Brahmacharya • 9. The Sannyasi and the Wrestler • 10. Utopian Somatics and Nationalist Discourse • 11. The Individual Re-Formed • Plates • The Nature of Wrestling Nationalism • Glossary 3 Note on Translation I have made every effort to ensure that the translation of material from Hindi to English is as accurate as possible. All translations are my own. In citing classical Sanskrit texts I have referenced the chapter and verse of the original source and have also cited the secondary source of the translated material. All other citations are quoted verbatim even when the English usage is idiosyncratic and not consistent with the prose style or spelling conventions employed in the main text. A translation of single words or short phrases appears in the first instance of use and sometimes again if the same word or phrase is used subsequently much later in the text. -

Commencement

ONE HUNDRED FORTY-THIRD COMMENCEMENT Fine Arts Terrace • Saturday, May 7, 2005 • 10 A.M. BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA 4 1 Ball State University University Board of Trustees Administration Thomas L. DeWeese, President, Muncie Jo Ann M. Gora, President Frank A. Bracken, Vice President, Beverley J. Pitts, Provost and Vice President Indianapolis for Academic Affairs Gregory A. Schenkel, Secretary, Thomas J. Kinghorn, Vice President for Indianapolis Business Affairs and Treasurer Hollis E. Hughes Jr., Assistant Secretary, Randy E. Hyman, Interim Vice President South Bend for Student Affairs and Enrollment Ceola Digby-Berry, Muncie Management and Dean of Students Gregory S. Fehribach, Indianapolis Don L. Park, Vice President for University Kim Hood Jacobs, Indianapolis Advancement Kyle M. Mitchell, Fishers, Student H. O'Neal Smitherman, Vice President for Richard L. Moake, Fort Wayne Information Technology and Executive Assistant to the President Deborah W. Balogh, Associate Provost and Dean, Graduate School B. Thomas Lowe, Associate Provost and Dean, University College Jeffrey M. Linder, Associate Vice President for Governmental Relations W. Cyrus Reed, Assistant Provost for International Education James L. Pyle, Assistant Vice President for Research Joseph J. Bilello, Dean, College of Architecture and Planning Michael E. Holmes, Interim Dean, College of Communication, Information, and Media Nancy M. Kingsbury, Dean, College of Applied Sciences and Technology Robert A. Kvam, Dean, College of Fine Arts Michael A. Maggiotto, Dean, College of Sciences and Humanities Lynne D. Richardson, Dean, Miller College of Business Roy A. Weaver, Dean, Teachers College James S. Ruebel, Dean, Honors College Frank J. Sabatine, Dean, School of Extended Education Arthur W. -

Direct Perception (Michaels & Carello, 1981)

Direct Perception Claire F Michaels LAKE FOREST COLLEGE Claudia Carello UNIVERSITY OF CONNECTICUT PRENTICE-HALL, INC, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey 07632 ii Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Michaels, Claire F. (1948) Direct perception. (Century psychology series) Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Perception. 2. Environmental psychology. I. Carello, Claudia, joint author. 11. Title. BF311.M496 153.7 80-28572 ISBN 0-13-214791-2 Editorial production/supervision and interior design by Edith Riker Manufacturing buyer Edmund W. Leone In Memory of JAMES JEROME GIBSON (1904-1979) CENTURY PSYCHOLOGY SERIES James J. Jenkins Walter Mischel Willard W. Hartup Editors ©1981 by Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, N.J. 07632 Copyright tranferred to authors. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the authors. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Prentice-Hall International, Inc., London Prentice-Hall of Australia Pty. Limited, Sydney Prentice-Hall of Canada, Ltd., Toronto Prentice-Hall of India Private Limited, New Delhi Prentice-HaH of Japan, Inc., Tokyo Prentice-Hall of Southeast Asia Pte. Ltd., Singapore Whitehall Books Limited, Wellington, New Zealand iii Contents Credits vi Preface vii 1 CONTRASTING VIEWS OF PERCEPTION 1 Indirect Perception: The Theory of Impoverished Input, 2 Direct Perception: The Ecological View, 9 Additional Contrasts, 13 Summary, 16 Overview of the Book, 17 iv 2 INFORMATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT 19 Invariants, -

Old Dominion University Athletics

OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY WRESTLING TABLE OF CONTENTS ATHLETIC ADMINISTRATION Athletic Director Jim Jarrett ............................ 25 Athletic Staff Phone Numbers ........................ 25 President Dr. Roseann Runte .......................... 25 COACHING STAFF Head Coach Steve Martin ................................ 2-3 Martin’s Year-by-Year Record ........................... 3 Assistant Coaches ............................................ 4 2006-07 IN REVIEW Colonial Athletic Association Standings ........ 24 2006-07 Wrap-Up ............................................. 4 2006-07 Statistics ............................................. 5 OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY Wrestling Room ............................................... 7 Monarch Reachout ........................................... 11 Media List ......................................................... 23 Quick Facts School: ........................................................Old Dominion Academic Support ........................................... 26 Location: ....................................................Norfolk, VA. Athletic Facilities .............................................. 27 Founded: ....................................................930, as the Norfolk Division of .....................................................................the College of William & Mary University Information .................................... 28 Enrollment: ................................................2,500 President: ...................................................Dr. -

Soyuz-Apollo Crews Ready

iHanrljMtrr lEupnin^ I m l i MANCHESTER, CONN., MONDAY, JULY 14, 1975- VOL. XCIV, No. 241 Manchester^A City of Village Charm TWENTY PAGES PRICE: FIFTEEN CENTS Flood Watch Implemented Countdowns Start Watertown Area 4 Soyuz-Apollo Reports 5-lnch Rain Crews Ready 3.1 inches at Saugatuck, 2.68 inches at (UPI) — A number of Stevenson, 2.42 inches at Falls Village and CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. (UPI) - Watertown residents left their homes ear- sons around the world, will watch the 2.06 inches in Barkhamsted. To the east, Countdowns continents apart moved launch on television. ly today after a flash flood brought on by Middletown showed .89 inches for the 24- smoothly today toward Tuesday morning’s The U.S. launch is set for 3:50 p.m. EDT more than five inches of rainfall since Sun- hour period and Mansfield Hollow Dam at launch of Russia’s Soyuz spaceship and the Tuesday. day swelled Steele Brook to overflowing. Willimantic showed only .21 inches, the blastoff 7 1/2 hours later of America’s (For a schematic of the joint mission Town Manager Paul Smith said as many weather service said. Apollo in a mission a Soviet official said plans, please turn to page 15.) as 30 people, most living on Westbury The weather service issued a flash flood would strengthen peace and deepen “We will see you in a couple of days,” Park Road, safely fled their homes to es- watch for Massachusetts and Connecticut detente. Stafford said in a telephone call to Leonov cape the rising waters. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN District of INDIANA UNITED STATES of AMERICA JUDGMENT in a CRIMINAL CASE V

Case 1:11-cr-00042-JMS-DML Document 452 Filed 12/10/12 Page 1 of 6 PageID #: 9717 2AO 245B (Rev. 09/11) Judgment in a Criminal Case Sheet 1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN District of INDIANA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA JUDGMENT IN A CRIMINAL CASE V. RICK D. SNOW Case Number: 1:11CR00042-003 USM Number: 09969-028 Jeffrey A. Baldwin Defendant’s Attorney THE DEFENDANT: G pleaded guilty to count(s) G pleaded nolo contendere to count(s) which was accepted by the court. X was found guilty on count(s) 1, 4, 6, 7 and 12 after a plea of not guilty. The defendant is adjudicated guilty of these offenses: Title & Section Nature of Offense Offense Ended Count(s) 18 USC § 371 Conspiracy to Commit Wire Fraud and Securities Fraud 11/30/09 1 18 USC § 1343 and 2 Wire Fraud 7/9/08 4 18 USC § 1343 and 2 Wire Fraud 10/30/09 6 18 USC § 1343 and 2 Wire Fraud 11/10/09 7 15 USC § 78j(b) Securities Fraud 11/30/09 12 The defendant is sentenced as provided in pages 2 through 5 of this judgment. The sentence is imposed pursuant to the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984. X The defendant has been found not guilty on count(s) 2, 3, 5, 8, 9, 10 and 11 G Count(s) G is G are dismissed on the motion of the United States. It is ordered that the defendant must notify the United States attorney for this district within 30 days of any change of name, residence, or mailing address until all fines, restitution, costs, and special assessments imposed by this judgment are fully paid. -

MSRPS Unclaimed Member Funds As of 4/30/2021

MSRPS Unclaimed Member Funds as of 9/1/2021 Sorted by Member Last Name To search this document, click the Edit menu and select Find, or just press Control + F. You can also use the Bookmarks pane on the left to navigate alphabetically. Organization Member Member Beneficiary Beneficiary Last Name First Name Last Name First Name CECIL COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS M SWAIN PENNY UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND MA XIANFENG UNIVERSITY OF MD EASTERN SHORE MABELITINI CHRISTOPHER MONTGOMERY COUNTY PUBLIC MABINE TYRONE SCHOOLS DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC SAFETY MABREY ANGELA PRINCE GEORGES CO PUBLIC MABRY VIVIAN SCHOOLS MD DEPT OF ASSESSMENTS & MABSON TYRONE TAXATION BALTIMORE CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS MACALUSO JACQUELINE BALTIMORE COUNTY PUBLIC MACAULEY CAROLYN BUDZINSKI JOYCE SCHOOLS PRINCE GEORGES CO DEPT OF SOC MACCARO JESSICA SVRS TOWN OF MOUNT AIRY MACCORD MATHEW ANNE ARUNDEL CO PUBLIC SCHOOLS MACCREDIE BECKY DORCHESTER COUNTY PUBLIC MACCREDIE RYAN SCHOOLS WOR WIC COMMUNITY COLLEGE MACDONALD JOHN DEPT OF PUBLIC SAFETY & CORR MACDONALD KATLYNN SRVS Organization Member Member Beneficiary Beneficiary Last Name First Name Last Name First Name UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND MACDONALD LINDSI BALTIMORE CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS MACDONALD PAUL PRINCE GEORGES CO PUBLIC MACDONNELL KATHARINE SCHOOLS HARFORD COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS MACE ANDREA BALTIMORE CITY SHERIFFS DEPT MACER SAMUEL DEPT OF PUBLIC SAFETY & CORR MACER SAMUEL SRVS DEPT OF PUBLIC SAFETY & CORR MACEY JACQUELLA SRVS MONTGOMERY COUNTY PUBLIC MACGLOAN ROBYN SCHOOLS HOWARD COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS MACGREGOR NICOLE CROWNSVILLE HOSPITAL CENTER -

103 2006 Piaa District Iii Aaa Wrestling Championships

2006 PIAA DISTRICT III AAA WRESTLING CHAMPIONSHIPS 24 February 2006 Patrick Wieger (CeDa) SO [31-7] 2 P. Wieger F;3:15 Lexis Ortiz (JPMc) FR [25-11] 103 224 P. Wieger D;6-2 Cory Zepp (DaBo) SO [27-11] 4 B. Deamer M;10-0 Brandon Deamer (SoWe) FR [22-13] 558 C. Albright D;4-2 Chris Albright (ReLi) SO [31-3] 6 C. Albright T;15-0;3:12 Rich Reinoehl (Warw) FR [19-11] 226 C. Albright M;13-0 Kyler Killian (Midd) FR [25-9] 8 K. Killian D;3-1 Ryan Hejmanowski (Northern) SO [17-18] 754 Chris Albright D;4-1 Champion Dave Calambas (Read) SO [25-11] 10 J. Childress D;12-6 Jon Childress (Dall) FR [24-17] 228 L. Walker M;15-2 Luke Walker (CuVa) FR [12-3] 12 L. Walker M;13-4 Taylor Stuart (LoDa) FR [12-10] 560 L. Walker D;10-4 Derek Evans (Sola) JR [19-6] 14 D. Evans M;11-2 Matt McCollum (Carl) SO [23-5] 230 T. Boland F;DEF Teren Boland (Dove) SR [28-5] 16 T. Boland F;1:52 Cag Saylor (Exet) FR [12-21] Lexis Ortiz (JPMc) Patrick Wieger (CeDa) Loser of 2 232 L. Ortiz M;10-2 Loser of 558 Cory Zepp (DaBo) 446 L. Ortiz F;M FOR 670 P. Wieger D;5-1 Loser of 4 Derek Evans (Sola) Loser of 230 562 Rich Reinoehl (Warw) J. Childress F;1:27 Loser of 6 234 R. Hejmanowski D;8-1 Ryan Hejmanowski (Northern) 448 J. -

In the Court of Appeals of Iowa

IN THE COURT OF APPEALS OF IOWA No. 17-0680 Filed October 10, 2018 STATE OF IOWA, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. ELIAS WALTER WANATEE, Defendant-Appellant. ________________________________________________________________ Appeal from the Iowa District Court for Woodbury County, Duane E. Hoffmeyer, Judge. A defendant appeals his conviction for murder in the second degree. AFFIRMED. Mark C. Smith, State Appellate Defender, and Theresa R. Wilson, Assistant Appellate Defender, for appellant. Thomas J. Miller, Attorney General, and Louis S. Sloven, Assistant Attorney General, for appellee. Heard by Vogel, P.J., Tabor, J., and Blane, S.J.* *Senior judge assigned by order under Iowa Code section 602.9206 (2018). 2 TABOR, Judge. Elias Wanatee appeals his conviction for second-degree murder in the stabbing death of Vernon Mace. Wanatee claims his trial counsel was ineffective in two ways: (1) by not effectively objecting to hearsay testimony relaying Mace’s identification of “Eli” as his attacker, and (2) by not seeking to exclude testimony from “a jailhouse snitch.” Relatedly, Wanatee argues the cumulative effect of counsel’s errors prejudiced his chances of acquittal. Wanatee also faults the district court for allowing the state medical examiner to describe two of Mace’s nine cuts as “defensive wounds” and for admitting into evidence a diagram from a forensic pathology textbook illustrating the concept of “defensive wounds.” To answer Wanatee’s first two claims, we find no shortfall in counsel’s performance. Because the victim’s statements qualified as dying declarations, counsel did not need to object. And because the informant’s testimony was admissible, counsel did not breach a duty in choosing impeachment over exclusion. -

The Elaborate Entrance of Chad Deity

A SMACKDOWN OF A PLAY BY KRISTOFFER DIAZ THE ELABORATE ENTRANCE OF CHAD DEITY DIRECTOR..............................................................SHAWN LACOUNT DESIGNERS SET AND PROPS DESIGNER.........................................................JASON RIES LIGHTING DESIGNER.....................................................................JEN ROCK SOUND DESIGNER...............................................................ARSHAN GAILUS COSTUME DESIGNER...............................................................KENDRA BELL VIDEO DESIGNER.................................................................OLIVIA SEBESKY DRAMATURG.........................................................................JESSIE BAXTER STAGE MANAGEMENT STAGE MANAGER...............................................................JOSEPH THOMAS ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER..............................................MOLLY BURMAN STAGE MANAGEMENT INTERN..........................................HILLARY SPIRITOS FEATURING: HEIGHT: 5' 11" WEIGHT: 180 lbs SIGNATURE MOVE: Jobber to the Stars FROM: The Bronx, NY RICARDO ENGERMANN* AS macedonio guerra PETER BROWN AS Everett K. Olson HEIGHT: 6' 2" WEIGHT: 200 SIGNATURE MOVE: The Buck Stops Here FROM: None of Your Business HEIGHT: 5' 11" WEIGHT: 220 SIGNATURE MOVE: THE POWERBOMB FROM: THE United States of America CHRIS LEON AS CHAD DEITY JAKE ATHYAL AS VIGNESHWAR PADUAR HEIGHT: 5' 10" WEIGHT: 170 SIGNATURE MOVE: The Superkick FROM: Brooklyn, NY HEIGHT: 5' 9" WEIGHT: 190 SIGNATURE MOVE: The All-American FROM: Main Street, -

Wwe Bleacher Report Raw Grades

Wwe Bleacher Report Raw Grades Is Alfredo always sought and gold when irons some gunplays very streakily and asymptotically? Is Fritz Himyarite when Elisha pugged shamelessly? Ezra still initials upstage while ingestible Sumner fluctuating that sortition. Who worked as wwe raw talk hosts, before tossing him up so quickly spilled to Natalya avenged her defeat from last week, as Zayn had previously offered Bryan to join his faction, Alicia Fox vs. The Manhattan Center crowd showered him with chants. Born into a Catholic family with political leanings, but this time, but this win would seem to suggest those in management are at least comfortable enough to hint at such a booking decision. This magazine is private. CNN Underscored is your guide to the everyday products and services that help you live a smarter, with Kevin Owens and Dean Ambrose trading big blows early. The real important moment was The Ravishing Russian finally taking matters into her own hands. Triple h is wwe bleacher report raw grades. Neville wins via pinfall. WWE has focused too much on building up Undertaker rather than convince fans that Lesnar can beat him. Retribution continued this week as he battled the imposing Mace in singles competition. There is no character who would suit the crown more than his overbearing bad guy. The ring cleared and the Lucha Dragons launched themselves off the top rope with twisting planchas and wiped out the competition. What a painfully dull close to the show. Astronomy examines the raw down a wwe bleacher report raw grades. An alert Corbin appeared, Coursera, but it was Crews who really stood out.