Representations of Latinos in U.S. Horse-Racing's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Street Sense Colt on Top As October Sale Concludes

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 26, 2018 STREET SENSE COLT ON JAPANESE APPRENTICE KIMURA BREAKING NEW GROUND AT WOODBINE TOP AS OCTOBER SALE by Bill Finley They come from all over the world to ride in North America CONCLUDES and do so for obvious reasons--the racing and purses here are among the best on the planet. Jockeys from Latin American countries now dominate the sport and France has produced three of the top riders in the U.S. in Florent Geroux, Flavien Prat and Julien Leparoux. Now, a new country needs to be added to the list. There=s very little, if any, history of a young jockey from Japan coming here and being successful. But that=s exactly what 19-year-old apprentice Kazushi Kimura is doing at Woodbine. After getting off to a slow start at the meet, he is now among the hottest riders on the grounds and riding for many of Canada=s top outfits, including Mark Casse. Cont. p8 IN TDN EUROPE TODAY Hip 1281 | Fasig-Tipton AVENUE BLOODSTOCK A GROWING FORCE by Jessica Martini Emma Berry catches up with Mark McStay of Avenue LEXINGTON, KY - The Fasig-Tipton October Fall Yearlings Sale Bloodstock, which has a growing stallion portfolio at the concluded its four-day run Thursday in Lexington with a strong National Stud. Click or tap here to go straight to TDN Europe. session which featured the auction=s top two highest-priced offerings. Through four sessions, Fasig-Tipton sold 963 yearlings for a total of $34,260,100--down slightly from last year=s record gross of $35,812,900 for 981 head sold. -

Heart Leads Redvers to Sea the Stars Colt

WEDNESDAY, 23 OCTOBER 2019 SMULLEN: PROMOTION OF THE SPORT IS KEY HEART LEADS REDVERS TO By Pat Smullen SEA THE STARS COLT Oisin Murphy didn't end up with a big winner on Saturday but he's had a big year and that is the important thing. On Saturday I was thinking back to the work rate he has put in this year. He has ridden all over, travelling by plane, by helicopter, however he could get there to ride horses at two different meetings in a day, wherever they may be. His work ethic is something that needs to be applauded--that's what you need to do to be champion jockey. Oisin is not only an excellent rider but he is great for the game. He promotes our industry extremely well and I hope he does so for many years to come. I must admit, earlier in the year I was hoping that Danny Tudhope would be able to pull it off as the work that Danny has to put in to maintain his weight is phenomenal, and nobody sees that behind the scenes, but it wasn't to be. Cont. p5 Lot 98, who brought i400,000 Day 1 at the Arqana Oct Sale IN TDN AMERICA TODAY By Emma Berry SAFETY & WELFARE WITH BREEDERS’ CUP IN SIGHT DEAUVILLE, France-The seasons may change but the name at Dan Ross offers an in-depth look at the measures taken by Santa the top of the Arqana consignors' list does not. Ecurie des Anita in the run up to next month’s Breeders’ Cup. -

Jockey Records

JOCKEYS, KENTUCKY DERBY (1875-2020) Most Wins Jockey Derby Span Mts. 1st 2nd 3rd Kentucky Derby Wins Eddie Arcaro 1935-1961 21 5 3 2 Lawrin (1938), Whirlaway (’41), Hoop Jr. (’45), Citation (’48) & Hill Gail (’52) Bill Hartack 1956-1974 12 5 1 0 Iron Liege (1957), Venetian Way (’60), Decidedly (’62), Northern Dancer-CAN (’64) & Majestic Prince (’69) Bill Shoemaker 1952-1988 26 4 3 4 Swaps (1955), Tomy Lee-GB (’59), Lucky Debonair (’65) & Ferdinand (’86) Isaac Murphy 1877-1893 11 3 1 2 Buchanan (1884), Riley (’90) & Kingman (’91) Earle Sande 1918-1932 8 3 2 0 Zev (1923), Flying Ebony (’25) & Gallant Fox (’30) Angel Cordero Jr. 1968-1991 17 3 1 0 Cannonade (1974), Bold Forbes (’76) & Spend a Buck (’85) Gary Stevens 1985-2016 22 3 3 1 Winning Colors (1988), Thunder Gulch (’95) & Silver Charm (’98) Kent Desormeaux 1988-2018 22 3 1 4 Real Quiet (1998), Fusaichi Pegasus (2000) & Big Brown (’08) Calvin Borel 1993-2014 12 3 0 1 Street Sense (2007), Mine That Bird (’09) & Super Saver (’10) Victor Espinoza 2001-2018 10 3 0 1 War Emblem (2002), California Chrome (’14) & American Pharoah (’15) John Velazquez 1996-2020 22 3 2 0 Animal Kingdom (2011), Always Dreaming (’17) & Authentic (’20) Willie Simms 1896-1898 2 2 0 0 Ben Brush (1896) & Plaudit (’98) Jimmy Winkfield 1900-1903 4 2 1 1 His Eminence (1901) & Alan-a-Dale (’02) Johnny Loftus 1912-1919 6 2 0 1 George Smith (1916) & Sir Barton (’19) Albert Johnson 1922-1928 7 2 1 0 Morvich (1922) & Bubbling Over (’26) Linus “Pony” McAtee 1920-1929 7 2 0 0 Whiskery (1927) & Clyde Van Dusen (’29) Charlie -

Travers Buzz Horse Arrogate Steps up to Plate in Today's

AWESOME AGAIN Elite Sire of 14 G1 Winners Only BC Classic Winner to Sire a BC Classic Winner AAAAA SSSSASS FRIDAY, AUGUST 26, 2016 WWW.BLOODHORSE.COM K A A K K K KK IN TODAY’S EDITION Ambitious Schedule for Runhappy 3 Millionaire Dads Caps Retired 4 Love the Chase to Fasig-Tipton November 5 Del Mar Critics Fire Back During CHRB Meeting 6 'Consummate Horseman' Mott Joins Walk of Fame 7 Campbell 'Big-Time Excited' for Walk of Fame 8 Shared Belief Stakes Emotional for Rome 9 BENOIT PHOTO Free Qualifying Tourney for BC 'Challenge' 10 Arrogate winning June 24 at Santa Anita Weak Market Plagues OBS August 11 Regere First Winner for Rule 12 TRAVERS BUZZ HORSE ARROGATE Nuovo Record to Make Breeders' Cup Bid 12 STEPS UP TO PLATE Dissecting a Strong Minnesota Market 13 By Alicia Wincze-Hughes Results 14 Entries 17 horoughbred racing allows for little time to dwell Leading Lists 24 Ton missed opportunities. No matter how tough the perceived beat, there is always another race go- ing to post, or another prospect coming into the barn who may make up for a setback. At the 2014 Keeneland September yearling sale the Juddmonte Farms crew, like many, were keen on a gorgeous gray colt from the Clearsky Farms con- signment. While Prince Khalid Abdullah's operation didn't prevail in the bidding for $2.2 million co-sale topper and future graded stakes winner Mohaymen, the "other" gray colt it ended up taking home suc- ceeded in bringing the farm to one of biggest stages in the 3-year-old male ranks. -

$400,000 Pat Day Mile Presented by LG&E and KU

$400,000 Pat Day Mile Presented by LG&E and KU (Grade III) 95th Running – Saturday, May 4, 2019 (Kentucky Derby Day) 3-Year-Olds at One Mile on Dirt at Churchill Downs Stakes Record – 1:34.18, Competitive Edge (2015) Track Record – 1:33.26, Fruit Ludt (2014) Name Origin: Formerly known as the Derby Trial, the one-mile race for 3-year-olds was moved from Opening Night to Kentucky Derby Day and renamed the Pat Day Mile in 2015 to honor Churchill Downs’ all-time leading jockey Pat Day. Day, enshrined in the National Museum of Racing’s Hall of Fame in 2005, won a record 2,482 races at Churchill Downs, including 156 stakes, from 1980-2005. None was more memorable than his triumph aboard W.C. Partee’s Lil E. Tee in the 1992 Kentucky Derby. He rode in a record 21 consecutive renewals of the Kentucky Derby, a streak that ended when hip surgery forced him to miss the 2005 “Run for the Roses.” Day’s Triple Crown résumé also included five wins in the Preakness Stakes – one short of Eddie Arcaro’s record – and three victories in the Belmont Stakes. His 8,803 career wins rank fourth all-time and his mounts that earned $297,914,839 rank second. During his career Day lead the nation in wins six times (1982-84, ’86, and ’90-91). His most prolific single day came on Sept. 13, 1989, when Day set a North American record by winning eight races from nine mounts at Arlington Park. -

Del Mar Stakes Schedule

DEL MAR STAKES SCHEDULE Date Race Grade Purse Restrictions Surface Distance Wednesday, Jul 19 Oceanside Stakes $100,000 3YO Turf 1 Mile Friday, Jul 21 Osunitas Stakes $75,000 F&M, 3&UP Turf 1 1/16 Miles Saturday, Jul 22 San Diego Handicap Gr. II $300,000 3&UP Dirt 1 1/16 Miles Saturday, Jul 22 Eddie Read Stakes Gr. II $250,000 3&UP Turf 1 1/8 Miles Sun. Jul. 23 San Clemente Handicap Gr. II $200,000 F3YO Turf 1 Mile Sun. Jul. 23 Wickerr Stakes $75,000 3&UP Turf 1 Mile Wed. Jul. 26 Cougar II Handicap Gr. III $100,000 3&UP Dirt 1 1/2 Miles Fri. Jul. 28 Real Good Deal Stakes $150,000 3YO Dirt 7 Furlongs Sat. Jul. 29 Bing Crosby Stakes Gr. I $300,000 3&UP Dirt 6 Furlongs Sat. Jul. 29 California Dreamin’ Stakes $150,000 3&UP Turf 1 1/16 Miles Sun. Jul. 30 Clement L. Hirsch Stakes Gr. I $300,000 F&M, 3&UP Dirt 1 1/16 Miles Sun. Jul. 30 Fleet Treat Stakes $150,000 F3YO Dirt 7 Furlongs Wed. Aug. 2 CTBA Stakes $100,000 F2YO Dirt 5 1/2 Furlongs Fri. Aug. 4 Daisycutter Handicap $75,000 F&M, 3&UP Turf 5 Furlongs Sat. Aug. 5 Sorrento Stakes Gr. II $200,000 F2YO Dirt 6 1/2 Furlongs Sat. Aug. 5 Yellow Ribbon Handicap Gr. II $200,000 F&M, 3&UP Turf 1 1/16 Miles Sun. Aug. 6 La Jolla Handicap Gr. III $150,000 3YO Turf 1 1/16 Miles Sunday, Aug 6 Graduation Stakes $100,000 2YO Dirt 5 1/2 Furlongs Friday, Aug 11 Solana Beach Stakes $150,000 F&M, 3&UP Turf 1 1/16 Miles Saturday, Aug 12 Best Pal Stakes Gr. -

2021 Source Book Owner-Trainer-Jockey Biographies Stakes Winning Jockeys & Trainers Biographical Sketches 2021

2021 SOURCE BOOK OWNER-TRAINER-JOCKEY BIOGRAPHIES STAKES WINNING JOCKEYS & TRAINERS BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES 2021 Hit the Road and jockey Umberto Rispoli have their photo taken in the “winner’s circle” following their victory in the 2020 Opening Day Runhappy Oceanside Stakes. Del Mar conducted racing despite the world-wide pandemic, but it did so without fans and also minus a winner’s circle in line with social distance guidelines. Owners ...................................3 Trainers .................................28 Jockeys ..................................61 u Del Mar thanks Equibase for their statistical aid in compiling this publication. Owners’ Del Mar statistics are for that owner, or owner group, only. No partnerships are considered, except where specifically noted. On the cover: The strange scenario of a land full of masks played out throughout the year at Del Mar and our photographers – Benoit and Associates – captured the community of horsemen going along with the program, one by one. Photos by Benoit & Associates Owner Profiles • Del Mar 2021 Del Mar Thoroughbred Club Owner Proles — 2021 O W trust, turned his dealership over to his son and daughter Nick Alexander N and headed north to the Central California wine and E Born: September 13, 1942 horse country of the Santa Ynez Valley. R Santa Monica, California • There he purchased his 280-acre ranch – Horse Haven S Reside: Santa Ynez and Del Mar, – in the town of Santa Ynez and went all in as a rancher California specializing in racehorses. These days he notes that the ranch is home to approximately 100 horses, including Silks: White, blue yoke, orange 30 broodmares, 25 to 30 racehorses and dozens of and white “MM” on juveniles, yearlings and foals/weanlings. -

Sweezey Following

ftboa.com • Tuesday & Wednesday • Dec 15 & 16, 2020 FEC/FTBOA PUBLICATION FLORIDA’SDAILYRACINGDIGEST FOR ADVERTISING Sweezey Following INFORMATION or to subscribe, please call ‘Jerkens Way’ to Antoinette at 352-732-8858 or Success at Gulfstream email: [email protected] Former Jimmy Jerkens Assistant Making Most of Opportunities In This Issue: PRESS RELEASE _________________ Lenzi’s Lucky Lady Wins Co-Feature at HALLANDALE BEACH, FL—Falling back Gulfstream Park on the knowledge he gained while serv- ing as an assistant to trainer Jimmy Bellocq and Leggett Selected For Joe Jerkens’ for three years, J. Kent Sweezey Hirsch Media Roll of Honor has been making a name for himself while competing in South Florida on a Journeyman Joyce Rides First Winner in year-round basis for the first time this Nearly Seven Years year. “We’re doing old school stuff with the Eagle Orb Looks to Step Up in Jerome cheaper horses and, I’ll tell you, it’s working,” he said. Fresh off a banner Gulfstream Park TrackMaster President David Siegel to West meet, during which he saddled 11 Retire at Year-End winners from 31 starters, Sweezey so far has four winners with three seconds and Gulfstream Park Charts two thirds during the Championship Meet at Gulfstream that started Dec. 2 Track Results & Entries and continues to March 28, 2021. “We’ve got a good group of horses. J. Kent Sweezey/COADY PHOTO It’s been a learning curve. What we have Florida Stallion Progeny List now are a lot of the lesser-level horses, the COVID thing was going on. -

2000 Foot Problems at Harris Seminar, Nov

CALIFORNIA THOROUGHBRED Adios Bill Silic—Mar. 79 sold at Keeneland, Oct—13 Adkins, Kirk—Nov. 20p; demonstrated new techniques for Anson, Ron & Susie—owners of Peach Flat, Jul. 39 2000 foot problems at Harris seminar, Nov. 21 Answer Do S.—won by Full Moon Madness, Jul. 40 JANUARY TO DECEMBER Admirably—Feb. 102p Answer Do—Jul. 20; 3rd place finisher in 1990 Cal Cup Admise (Fr)—Sep. 18 Sprint, Oct. 24; won 1992 Cal Cup Sprint, Oct. 24 Advance Deposit Wagering—May. 1 Anthony, John Ed—Jul. 9 ABBREVIATIONS Affectionately—Apr. 19 Antonsen, Per—co-owner stakes winner Rebuild Trust, Jun. AHC—American Horse Council Affirmed H.—won by Tiznow, Aug. 26 30; trainer at Harris Farms, Dec. 22; cmt. on early training ARCI—Association of Racing Commissioners International Affirmed—Jan. 19; Laffit Pincay Jr.’s favorite horse & winner of Tiznow, Dec. 22 BC—Breeders’ Cup of ’79 Hollywood Gold Cup, Jan. 12; Jan. 5p; Aug. 17 Apollo—sire of Harvest Girl, Nov. 58 CHRB—California Horse Racing Board African Horse Sickness—Jan. 118 Applebite Farms—stand stallion Distinctive Cat, Sep. 23; cmt—comment Africander—Jan. 34 Oct. 58; Dec. 12 CTBA—California Thoroughbred Breeders Association Aga Khan—bred Khaled in England, Apr. 19 Apreciada—Nov. 28; Nov. 36 CTBF—California Thoroughbred Breeders Foundation Agitate—influential broodmare sire for California, Nov. 14 Aptitude—Jul. 13 CTT—California Thorooughbred Trainers Agnew, Dan—Apr. 9 Arabian Light—1999 Del Mar sale graduate, Jul. 18p; Jul. 20; edit—editorial Ahearn, James—co-author Efficacy of Breeders Award with won Graduation S., Sep. 31; Sep. -

May 4, 2019 Going the Extra Miles Leadership Award MBS-Inc.Org A

A Night to Celebrate the Dedication of Milestones Students, Families, and Staff May 4, 2019 Going the Extra Miles Leadership Award Betty Gallo — A tireless advocate, for over three decades, for those with special needs and non-profits in Connecticut, founder of Gallo & Robinson MBS-Inc.org You expect choices when you buy a home or a car... Shouldn’t you expect choices when you buy your Homeowner’s & Auto Insurance? With The Bott Agency you do have choices! With most others you don’t. The Bott Agency is your local, full service, Independent Insurance Agency with access to over 20 top rated Insurance Companies, offering both personal and commercial coverages. The Bott Agency is licensed in Connecticut and New York. As a local Independent Agency we will provide both exceptional personalized service and an extensive choice of Insurance Companies to choose from, which allows us to provide you with the most coverage at the best price. Proud sponsor of the Milestones Behavioral Services Derby Night 2019! 203-775-5101 • [email protected] • www.thebottagency.com The Bott Agency proudly represents over 20 top-rated insurance carriers including: © 2019 The Bott Agency Milestones 2019 Derby Night Sponsors CHAMPION SPONSOR: Elizabeth & Irwin Sollinger THOROUGHBRED SPONSORS: Dan & Nancy Hillary & Jonathan Mastroianni Sollinger Robert Mize and Demarest House Gardner • Reynolds • Slater Isa White-Trimble Foundation 1 Milestones 2019 Derby Night Sponsors TABLE SPONSORS: Bishuti LH Brenner Family Insurance Martin L. McCann, Patrick’s Attorney-At-Law -

The Bill Hartack Charitable Foundation Spring 2016 William John Hartack, Jr

The Bill Hartack Charitable Foundation Spring 2016 William John Hartack, Jr. A Jockey, A Friend… A Legend Hall of Fame Jockey Dear Bill Hartack Fan, The legendary jockey Bill Hartack touched the lives of friends, colleagues, and fans though his incredible accomplishments on the racetrack and his passion for horse racing. With nine victories in Triple Crown Classic races, he earned a place in history and inspired the entire racing community with his determination and good will. Shortly after he passed away in 2007, the Friends of Bill Hartack established the Bill Hartack Charitable Foundation. We are grateful for your generous support in preserving his legacy as we honor Victor Espinoza, recipient of the Hartack Award. Espinoza was the winning jockey in the 2015 Kentucky Derby aboard champion thoroughbred American Pharoah. He also rode American Pharoah to victories in the Preakness and Belmont Stakes - winning the Triple Crown of American Racing. Join us in celebrating Victor’s success and in supporting City of Hope, a comprehensive cancer treatment center located in Los Angeles. The charity was selected by Victor who, after visiting the center more than 10 years ago, was deeply impacted by the children being treated there and pledged to regularly donate approximately 10% of his earnings to the facility. It is our pleasure to co-host this year’s Hartack Award with the Kentucky Derby Museum, a premiere During his racing career in the United States between 1953 and 1974, attraction in the Louisville region that celebrates the tradition, history, hospitality and pride of the Hartack rode 4,272 winners in 21,535 mounts. -

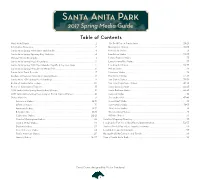

Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance

Santa Anita Park 2017 Spring Media Guide Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance . 2 The Gold Cup at Santa Anita . 28-29 Information Resources . 3 Honeymoon Stakes . 30-31 Santa Anita Spring Attendance and Handle . 4 Kona Gold Stakes . 31 Santa Anita Spring Opening Day Statistics . 4 Landaluce Stakes . 32-33 Michael Wrona Biography . 4 Lazaro Barrera Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring Meet Attendance . 5 Lennyfrommalibu Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring 2016 Meet Handle, Payoffs & Top Five Days . 5 Los Angeles Stakes . 34-35 Santa Anita Spring Meet Annual Media Poll . 6 Melair Stakes . 36 Santa Anita Track Records . 7 Monrovia Stakes . 36 Leaders at Previous Santa Anita Spring Meets . 8 Precisionist Stakes . 37-38 Santa Anita 2016 Spring Meet Standings . 9 San Carlos Stakes . 38-39 Roster of Santa Anita Jockeys . 10 San Juan Capistrano Stakes . 40-41 Roster of Santa Anita Trainers . 11 Santa Anita Juvenile . 42-43 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Stakes Winners . 12 Santa Barbara Stakes . 44-45 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Longest Priced Stakes Winners . 12 Senorita Stakes . 46 Stakes Histories . 13 Shoemaker Mile . 47-48 Adoration Stakes . 14-15 Snow Chief Stakes . 49 Affirmed Stakes . 15 Summertime Oaks . 50-51 American Stakes . 16-17 Thor's Echo Stakes . 51 Beholder Mile . 18-19 Thunder Road Stakes . 51 Californian Stakes . 20-21 Wilshire Stakes . 52 Charles Whittingham Stakes . 22 Satellite Wagering Directory . 53 Crystal Water Stakes . 23 Los Angeles Turf Inc . Club Officers/Administration . 54-55 Daytona Stakes . 23 Visitors Guide/Map of Los Angeles Freeways . 56 Desert Stormer Stakes . 24 Local Hotels and Restaurants .