Racial Profiling and the Internment's True Legacy Eric L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pocket a R T Collective

C O V E R A R T I S T : D A N A B R O W N F I E L D E U N I V E R S I T Y P L A C E L I B R A R Y V I S T E C N I E Z L E L K O A C M S T N R E A E T T E K C 1 2 0 2 E N U J / 1 0 E U S S I O P POCKET ART COLLECTIVE Issue 01 | June 2021 TEEN CONTRIBUTORS: Chester Chloe Bowden Elijah Johnson What are zines? Emrys Hutch Zines are Isabella Souza small-press Lemon Smith independently-published Mädchen Kirkhart Maya Sharma magazines @shiroshusband Worra Ribitsch with a history in alternative, counter- Zena Willard culture, or underground communities. *names reflect contributor preferences The Pocket Art Collective zine is STAFF CONTRIBUTORS: compiled of contributions from teens in Pierce County Washington. Alex Byrne Dana Brownfield Learn more about zines at Dawn Riggs https://guides.library.cornell.edu/zines101 Cover Art: Nerves, 2020, watercolor Artist Statement: During 2020 I made several paintings and drawings inspired by mandala art. I found it very soothing to take imagery that felt chaotic or stressful and put it into a structured, geometric form with lots of repetition and minute details. I was feeling anxious when I made this example and focused on how the emotions physically felt and chose forms and colors inspired by those feelings. The painting is made with watercolor. -

M.G. Parker Memorial Library Off the Shelf: the Official Newsletter of the Parker Library

April 2019 M.G. Parker Volume 4 | Issue 4 Memorial Library 28 Arlington Street Dracut, MA 01826 (978) 454-5474 www.dracutlibrary.org Off the Shelf: The Official Newsletter of the Parker Library Artists Wanted To be considered, artists Laura is a 2002 graduate must fill out an Artist of Emmanuel College in Agreement and Release | Boston, where she Indemnification Form, an received her degree in Exhibit Application, and Vocal Performance, examples of materials to be Theatre Arts, and Speech exhibited as hard copies or Communication. For 19 electronic format, or years, she was a member provide a web address of the Tanglewood Festival The Parker Library is now showing their artwork. Chorus, resident chorus for offering exhibition space in the Boston Symphony and our Meeting Room for the For a copy of the policy the Boston Pops. She displaying of original and form, please contact appeared as a soloist for artwork(s). Library Director, Nanci the Boston Symphony and Milone Hill at Boston Pops multiple times Artists from outside of [email protected] over the course of those 19 Dracut are welcome to years. She has recorded Musical Mondays with the Boston Symphony apply for a display period, but preferences will be and the Pops, as well as given as indicated below: the progressive rock group Telergy, and most Dracut resident Artists or notably for James Taylor, Artworks directly related to on his "One Man Band" Dracut. recording. She has sung all over the world, including at NDEX Affiliations with town Sinatra Meets Soprano the BBC Proms in London, associated with the Monday, 4/1 at 6:30 PM and the Saito Kinen Artists Wanted 1 Merrimack Valley Library Festival in Matsumoto, Japan. -

Silent Honor Free

FREE SILENT HONOR PDF Danielle Steel | 416 pages | 01 Oct 1997 | Random House Publishing Group | 9780440224051 | English | none Silent Honor by Danielle Steel Uh-oh, it looks like your Internet Explorer is out of date. For a better shopping Silent Honor, please upgrade now. Javascript is Silent Honor enabled in your browser. Enabling JavaScript in your browser will allow you to experience all the features of our site. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. NOOK Book. From Silent Honor New York Times bestselling author Danielle Steel, a moving novel of families separated and lives shattered by prejudice during one of the most shameful episodes in American history. It was August From the ship, she went to the Palo Alto home of her uncle, Takeo, and his family. To Hiroko, California Silent Honor a different world. Her cousins had become more American than Japanese. On December 7, Pearl Harbor is bombed by the Japanese. Within hours, war is declared and suddenly Hiroko has become an enemy in a foreign land. On February 19, Executive Order is signed by President Roosevelt, giving the military the power to remove the Japanese from their communities Silent Honor will. Takeo and his family are given ten days to sell their home, give up their jobs, and report to a relocation center, along with thousands of other Japanese and Japanese Americans, to face their destinies there. Families are divided, people are forced to abandon their Silent Honor, their businesses, their freedom, and their lives. Danielle Steel portrays not only the human cost of that terrible time in history, but also the remarkable courage of a people whose honor and dignity transcended the chaos that surrounded them. -

Bookworms and Their Diets Dothan, Alabama Spring 2016 Delozier, Kim & Jourdan, Carolyn NON-FICTION Bear in the Back Seat

Bookworms and Their Diets Dothan, Alabama Spring 2016 NON-FICTION DeLozier, Kim & Jourdan, Carolyn Bear in the Back Seat: Adventures of a Wildlife Ranger in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park (Vol. 1 & Vol. 2 ) Ranger DeLozier’s adventures with befuddled bears, hormonally-crazed elk, homicidal wild boars, hopelessly timid wolves and nine million tourists, some of whom are clueless. Houston, Jeanne Wakatsuki and James D. Houston Farewell to Manzanar The Houstons follow the lives of Jeanne and her Japanese family during World War II in Manzanar internment camp. Larson, Kate Clifford Bound for the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman: Portrait of an American Hero Harriet Tubman, born a slave in 1822 in Maryland, escaped in1849, and began a life of sacrifice helping others escape to freedom. Russell, Jan Jarboe The Train to Crystal City: FDR's Secret Prisoner Exchange Program and America's Only Family Internment Camp During World War II Japanese, German, and Italian immigrants and their American-born children were forcibly transported to Crystal City, TX, internment camp, a center of a government prisoner exchange program called “quiet passage.” Hundreds of prisoners in Crystal City were exchanged for other more important Americans—diplomats, businessmen, soldiers, and missionaries—behind enemy lines in Japan and Germany. Smith, Charlotte Paw Prints in Oman: Dogs, Mogs and Me British expatriate, Charlotte, living with her husband in Oman, is a vet clinic volunteer who finds homes for hundreds of stray cats and dogs. Earthquakes, cultural differences, tears and laughter follow as seven years flash by. Weintraub, Stanley Silent Night The Story of the World War I Christmas Truce In the early months of World War I, on Christmas Eve, men on both sides of the trenches laid down their arms and joined in a spontaneous celebration. -

A Chronology of Danielle Steel Novels the NUMBERS GAME March 2020 Hardcover (9780399179563) MORAL COMPASS January 2020 Hardcov

A Chronology of Danielle Steel Novels THE NUMBERS GAME March 2020 Hardcover (9780399179563) MORAL COMPASS January 2020 Hardcover (9780399179532) SPY November 2019 Hardcover (9780399179440) CHILD’S PLAY October 2019 Hardcover (9780399179501) THE DARK SIDE August 2019 Hardcover (9780399179419) LOST AND FOUND June 2019 Hardcover (9780399179471) March 2020 Paperback (9780399179495) BLESSING IN DISGUISE May 2019 Hardcover (9780399179327) January 2020 Paperback (9780399179341) SILENT NIGHT March 2019 Hardcover (9780399179389) December 2020 Paperback (9780399179402) TURNING POINT January 2019 Hardcover (9780399179358) July 2019 Paperback (9780399179372) BEAUCHAMP HALL November 2018 Hardcover (9780399179297) October 2019 Paperback (9780399179310) IN HIS FATHER’S FOOTSTEPS September 2018 Hardcover (9780399179266) May 2019 Paperback (9780399179280) THE GOOD FIGHT July 2018 Hardcover (9781101884126) March 2019 Paperback (9781101884140) THE CAST May 2018 Hardcover (9781101884034) January 2019 Paperback (9781101884058) ACCIDENTAL HEROES March 2018 Hardcover (9781101884096) December 2018 Paperback (9781101884119) FALL FROM GRACE January 2018 Hardcover (9781101884003) October 2018 Paperback (9781101884027) PAST PERFECT November 2017 Hardcover (9781101883976) August 2018 Paperback (9781101883990) FAIRYTALE October 2017 Hardcover (9781101884065) May 2018 Paperback (9781101884089) THE RIGHT TIME August 2017 Hardcover (9781101883945) April 2018 Paperback (9781101883969) THE DUCHESS June 2017 Hardcover (9780345531087) February 2018 Paperback (9780425285411) -

Anxiety of Ward in Daniel Steel's Family Album: a Psychoanalitic Perspective School of Teacher Training and Education

ANXIETY OF WARD IN DANIEL STEEL'S FAMILY ALBUM: A PSYCHOANALITIC PERSPECTIVE Research Paper Submitted as the Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Getting Bachelor Degree of English Department by RATIH TRI WASTIANI A 320 020 117 SCHOOL OF TEACHER TRAINING AND EDUCATION 1 MUHAMMADIYAH UNIVERSITY OF SURAKARTA 2009 2 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of the Study Literary works, as human's creation, are the reflection of human feeling and imagination about life. It describes sadness, happiness, hope and other phenomena that appear in society. The phenomena which happen in society will be the experience for human beings at that time: and it will be different from one another. Experience is apart of human being that cannot be separated from their lives. They have their own experience that different from one to another and it cannot be explained in a few sentences. It has many things that deal with the life of human being that influences their lives. They are dynamic, so that human beings are always in activity and it means that they change from time to time. This make them realize that they have seen and noticed any event. These events improve human beings knowledge and awareness their future, they will be better facing their lives. Human beings experience many events about sadness and happiness. These are manifested in literature, Culler States that: Literature is a continual exploration of and reflections upon significant in all its from: an interpretations of experiences a commentary on the validity of various ways of interpreting experience, an explorations of the creative, revelatory and deceptive powers of language, a critique of the code and interpretive processes manifested in our languages and in previous literature (Culler in Teeuw, 1984 : 143) From the statement above, it can be pointed out that literary work is human's creations that reflects human feeling and imagination about life. -

Masterarbeit / Master's Thesis

MASTERARBEIT / MASTER’S THESIS Titel der Masterarbeit / Title of the Master‘s Thesis „Breaking the Silence: An analysis of family memory and identity construction in Japanese-American internment novels“ verfasst von / submitted by Sophie Asamer BA BA angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) Wien, 2018 / Vienna 2018 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt / A 066844 degree programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt / Masterstudium Anglophone Literatures and degree programme as it appears on Cultures UG2002 the student record sheet: Betreut von / Supervisor: Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Alexandra Ganser-Blumenau Acknowledgments: The finalization of this thesis marks an important step for me, not only academically, but also as a personal achievement. While getting to this point was not always easy, I am immensely grateful for the opportunity to broaden my knowledge on so many levels. I would like to thank my supervisor, Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Alexandra Ganser-Blumenau for her help with gathering my thoughts and great suggestions for further reading. I would also like to thank my family, who was so incredibly patient with me over the last years, my boyfriend for his endless support and encouragements, and Jenny Atkinson, who is a great friend and played an essential part in helping me finalize this project. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... -

Large Print Bibliography 2010

Large Print Bibliography Talking Book Program Reader Services www.TexasTalkingBooks.org Texas State Library and Archives Commission NOTES: LARGE PRINT BIBLIOGRAPHY Books Recently Added to Collection Updated July 2010 Large print titles are listed under the following categories, arranged alphabetically by author, then alphabetically by title under each author. A title may be listed under more than one category. For more information about these or other available titles, contact the Talking Book Program. RECENTLY ADDED FICTION… RECENTLY ADDED NONFICTION… BIOGRAPHY… CHILDREN’S / YOUNG ADULT… CHRISTIAN FICTION / RELIGIOUS FICTION… Reader Services CHRISTIAN MYSTERY… CHRISTIAN ROMANCE… CHRISTMAS STORIES… CLASSICS… Texas State Library and COZY MYSTERY… Archives Commission GENERAL FICTION… HISTORICAL FICTION… HISTORY… P.O. Box 12927 MYSTERY / THRILLER / SUSPENSE / SPY… Austin, TX 78711-2927 (See also: CHRISTIAN MYSTERY) 1-800-252-9605 (See also: COZY MYSTERY) (512) 463-5458 (See also: ROMANTIC SUSPENSE) www.TexasTalkingBooks.org NONFICTION… POETRY… ROMANCE… (See also: CHRISTIAN ROMANCE) ROMANTIC SUSPENSE… SHORT STORIES… SUPERNATURAL FICTION… TRUE CRIME… WESTERN… RECENTLY ADDED FICTION Adam, Paul Paganini’s Ghost Barton, Beverly LB 6329 Worth Dying For Albert, Susan Wittig Cottage Tales of Beatrix Potter series: Baum, L. Frank LB 6224 The Tale of Holly How #2 LB 3585 Wonderful Wizard of Oz Alcott, Louisa May Bishop, Curtis LB 3842 Good Wives: Little Women, LB 6252 By Way of Wyoming Part II LB 4905 Rose in Bloom Blake, Sarah LB 6420 The Postmistress Anaya, Rudolfo LB 6203 Bless Me, Ultima Blume, Judy LB 6053 Are You There, God? It’s Me, Atherton, Nancy Margaret LB 6239 Aunt Dimity Slays the Dragon LB 3728 Blubber LB 3726 Deenie Austen, Jane LB 3956 Starring Sally J. -

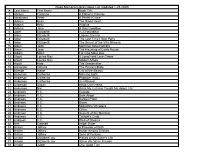

Last Name First Name Book Title 1 Aarsen Carolyne A

Wage Memorial Library Book List (Updated 1-29-2020) # Last Name First Name Book Title 1 Aarsen Carolyne A Father's Promise 2 Abrahams Peter A Perfect Crime 3 Adams Kelly The Silent Heart 4 Adams Kelly Wildfire 5 Adams Jane A Kiss Goodbye 6 Adler Elizabeth In A Heartbeat 7 Adler Elizabeth Legacy Secrets 8 Adler Elizabeth The Last Time I Saw Paris 9 Adler Elizabeth The Secret of the Villa Mimosa 10 Aiken Joan Mortimer Says Nothing 11 Aiken Joan The Haunting of Lamb House 12 Albom Mitch For One More Day 13 Alcott Louisa May A Long Fatal Love Chase 14 Alcott Louisa May Modern Magic 15 Alcott Kate The Dressmaker 16 Alexander Victoria The Prince's Bride 17 Allende Isabel City of the Beasts 18 Anderson Catherine Morning Light 19 Anderson Catherine Phantom Waltz 20 Anderson Catherine Sun Kissed 21 Anderson Susan Head Over Heels 22 Anderson Niki What My Cat Has Taught Me About Life 23 Andrews V.C. Celeste 24 Andrews V.C. Dark Angel 25 Andrews V.C. Darkest Hour 26 Andrews V.C. Dawn 27 Andrews V.C. Midnight's Whispers 28 Andrews V.C. Olivia 29 Andrews V.C. Secrets of the Morning 30 Andrews V.C. Twilight's Child 31 Andrews V.C. Web of Dreams 32 Ann Gabhart Angel Sister 33 Archer Jeffrey A Prisoner of Birth 34 Archer Jeffrey Honor Among Thieves 35 Archer Jeffrey Sons of Fortune 36 Arnold Elizabeth Joy Pieces of My Sister's Life 37 Arnold Elizabeth Joy When We Were Friends 38 Arnold Judith One Good Turn 39 Athanas Verne Pursuit 40 Atherton Nancy Aunt Dimity Beats The Devil 41 Atwood Margaret Cat's Eye 42 Auel Jean The Plains of Passage 43 Auel Jean -

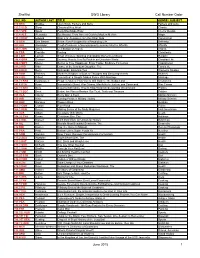

Shelflist DWO Library Call Number Order June 2015 1

Shelflist DWO Library Call Number Order CALL NO. AUTHOR LAST TITLE GENRE / SUBJECT 070 BRA Bradlee Life's Work: Fathers and Sons Fathers and sons 133.3 SLO Sloan Ghosts of Key West Ghosts 133.3 SPE Spear Feng Shui Made Easy Interior Design 133.4 ALE Alexander Spellbound: From Ancient Gods to Modern Merlins Magic 133.9 EDW Edward After Life: Answers From the Other Side Paranormal 170 DEN Den Besten Shine: Five Principles for a Rewarding Life Self-help 202 ALE Alexander Proof of Heaven: a Neurosurgeon's Journey Into the Afterlife Afterlife 235.3 JON Jones Celebration of Angels Angels 248 FRA Franklin Fasting Christianity 248 LAM Lamott Small Victories: Spotting Improbable Moments of Grace Religion 248.4 GRA Graham Journey: How to Live By Faith in an Uncertain World Christian Life 248.4 MEY Meyer Secret to True Happiness: Enjoy Today, Embrace Tomorrow Inspirational 291.2 KID Kidd Dance of the Dissident Daughter, The Family life 305.4 BER Berry Girlfriends: Enduring Ties Women's Studies 306 RAM Ramsey Mother's Wisdom: a Book of Thoughts and Encouragements Mothers 306.8 GIL Gilbert Committed: a Skeptic Makes Peace With Marriage Marriage 336.73 RAS Rasmussen People's Money: How Voters Will Balance the Budget and … Economics 341.6 RYA Ryan Yamashita's Ghost: War Crimes, MacArthur's Justice, and Command… War Crimes 342.73 BEC Beck Arguing With Idiots: How to Stop Small Minds and Big Government Politics 342.73 BEC Beck Broke: the Plan to Restore Our Trust, Truth and Treasure Politics 355 CLA Clancy Every Man a Tiger Military Science 355 WEI Weir -

A-Chronology-Of-Danielle-Steel-Novels-March-2016.Pdf

A Chronology of Danielle Steel Novels BLUE January 2016 Hardcover (978-0-345-53105-6) PRECIOUS GIFTS December 2015 Hardcover (978-0-345-53103-2) UNDERCOVER September 2015 Hardcover (978-0-345-53104-9) COUNTRY June 2015 Hardcover (978-0-345-53100-1) PRODIGAL SON February 2015 Hardcover (978-0-385-34315-2) January 2016 Paperback (978-0-440-24518-6) PEGASUS October 2014 Hardcover (978-0-345-53097-4) November 2015 Paperback (978-0-345-53098-1) PRETTY MINNIE IN PARIS (for children) October 2014 (978-0-385-37000-4) A PERFECT LIFE July 2014 Hardcover (978-0-345-53094-3) June 2015 Paperback (978-0-345-53095-0) POWER PLAY March 2014 Hardcover (978-0-345-53091-2) January 2015 Paperback (978-0-345-53092-9) WINNERS October 2013 Hardcover (978-0-385-34322-0) September 2014 Paperback (978-0-440-24525-4) PURE JOY (nonfiction book about dogs) October 2013 Hardcover (978-0-345-54375-2) FIRST SIGHT July 2013 Hardcover (978-0-385-33830-1) April 2014 Paperback (978-0-440-24205-5) UNTIL THE END OF TIME January 2013 Hardcover (978-0-345-53088-2) January 2014 Paperback (978-0-345-53089-9) THE SINS OF THE MOTHER October 2012 Hardcover (978-0-385-34320-6) September 2013 Paperback (978-0-440-24523-0) A GIFT OF HOPE (short book about helping the homeless) October 2012 Hardcover (978-0-345-53136-0) October 2013 Paperback (978-0-345-53206-0) FRIENDS FOREVER July 2012 Hardcover (978-0-385-34321-3) June 2013 Paperback (978-0-440-24524-7) BETRAYAL March 2012 Hardcover January 2013 Paperback (978-0-440-24522-3) HOTEL VENDOME November 2011 Hardcover (978-0-385-34317-6) -

A Chronology of Danielle Steel Novels DADDY's GIRLS June 2020

A Chronology of Danielle Steel Novels DADDY’S GIRLS June 2020 Hardcover (9780399179624) THE WEDDING DRESS April 2020 Hardcover (9780399179594) THE NUMBERS GAME March 2020 Hardcover (9780399179563) MORAL COMPASS January 2020 Hardcover (9780399179532) SPY November 2019 Hardcover (9780399179440) CHILD’S PLAY October 2019 Hardcover (9780399179501) July 2020 Paperback (9780399179525) THE DARK SIDE August 2019 Hardcover (9780399179419) May 2020 Paperback (9780399179433) LOST AND FOUND June 2019 Hardcover (9780399179471) March 2020 Paperback (9780399179495) BLESSING IN DISGUISE May 2019 Hardcover (9780399179327) January 2020 Paperback (9780399179341) SILENT NIGHT March 2019 Hardcover (9780399179389) December 2020 Paperback (9780399179402) TURNING POINT January 2019 Hardcover (9780399179358) July 2019 Paperback (9780399179372) BEAUCHAMP HALL November 2018 Hardcover (9780399179297) October 2019 Paperback (9780399179310) IN HIS FATHER’S FOOTSTEPS September 2018 Hardcover (9780399179266) May 2019 Paperback (9780399179280) THE GOOD FIGHT July 2018 Hardcover (9781101884126) March 2019 Paperback (9781101884140) THE CAST May 2018 Hardcover (9781101884034) January 2019 Paperback (9781101884058) ACCIDENTAL HEROES March 2018 Hardcover (9781101884096) December 2018 Paperback (9781101884119) FALL FROM GRACE January 2018 Hardcover (9781101884003) October 2018 Paperback (9781101884027) PAST PERFECT November 2017 Hardcover (9781101883976) August 2018 Paperback (9781101883990) FAIRYTALE October 2017 Hardcover (9781101884065) May 2018 Paperback (9781101884089)