What Every Allstate Insured Needs to Know

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kenmore Appliance Warranty Master Protection Agreements One Year Limited Warranty Congratulations on Making a Smart Purchase

Kenmore Appliance Warranty Master Protection Agreements One Year Limited Warranty Congratulations on making a smart purchase. Your new Ken- When installed, operated and maintained according to all more® product is designed and manufactured for years of instructions supplied with the product, if this appliance fails due dependable operation. But like all products, it may require to a defect in material or workmanship within one year from the preventive maintenance or repair from time to time. That’s when date of purchase, call 1-800-4-MY-HOME® to arrange for free having a Master Protection Agreement can save you money and repair. aggravation. If this appliance is used for other than private family purposes, The Master Protection Agreement also helps extend the life of this warranty applies for only 90 days from the date of pur- your new product. Here’s what the Agreement* includes: chase. • Parts and labor needed to help keep products operating This warranty covers only defects in material and workman- properly under normal use, not just defects. Our coverage ship. Sears will NOT pay for: goes well beyond the product warranty. No deductibles, no functional failure excluded from coverage – real protection. 1. Expendable items that can wear out from normal use, • Expert service by a force of more than 10,000 authorized including but not limited to fi lters, belts, light bulbs and bags. Sears service technicians, which means someone you can 2. A service technician to instruct the user in correct product trust will be working on your product. installation, operation or maintenance. • Unlimited service calls and nationwide service, as often as 3. -

GENERAL GROWTH PROPERTIES, INC. 2001 Annual Report on Behalf of All the Employees Of

GENERAL GROWTH PROPERTIES, INC. 2001 annual report On behalf of all the employees of General Growth Properties, I would like to extend our condolences to anyone who lost a loved one, a friend, an acquaintance or a co-worker in The regional mall business is about relationships. the tragedy of September 11, 2001. We do not forge them lightly, but with the intent We are a country of strong individuals to nurture and strengthen them over time. Even in periods of distress, the relationships with who will continue to unite as we have rock solid our consumers, owners, retailers, and employees keep throughout our history.We will not us rooted in one fundamental belief: that success can be achieved allow horrific acts of terrorism to destroy when we work together.The dynamics of our the greatest and most powerful nation industry dictate that sustainability is contingent upon in the world. God bless you. the integrity of our business practices.We will never lose sight of this fact and will carry out every endeavor to reflect the highest standards. contents Financial Highlights . lift Portfolio . 12 Company Profile . lift Financial Review . 21 Operating Principles . 2 Directors and Officers . 69 Shareholders’ Letter . 4 Corporate Information . 70 Shopping Centers Owned at year end includes Centermark 1996 75 company profile General Growth Properties and its predecessor companies 1997 64 have been in the shopping center business for nearly fifty years. It is the second largest regional 1998 84 mall Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) in the United States. General Growth owns, develops, 1999 93 operates and/or manages shopping malls in 39 states. -

Scrip Order Form

St. Thomas Aquinas SCRIP ORDER FORM Thank you! Your support is greatly appreciated! Please remember that we can sell only the amounts listed on the order form. Name:_______________________________________________Phone:___________________Date:_______________ Check# :_________________Amount:__________________ * Please make checks payable to: St. Thomas Aquinas * Filled by__________NEEDS:________________________________________________________________________ Retailer Profit Card Qty. Total Retailer Profit Card Qty. Total (c.o.a.) = certificate on account for Amount (c.o.a.) = certificate on for Amount school account school $5.00 $100 Claire’s $0.90 $10 All Seasons Gutter/New All Seasons Gutter/Topper $10.00 $100 Cold Stone $0.80 $10 Creamery American Eagle Outfitters $2.00 $25 Courtyard/Marriott $6.00 $50 Applebees $2.00 $25 Critter $0.50 $10 Nation(Dyvig’s) Arby’s $0.80 $10 Barnes & Noble/B. Dalton $1.00 $10 Derry Auto (c.o.a.) $1.00 $25 Barnes & Noble/B. Dalton $2.50 $25 Derry Auto (c.o.a.) $2.50 $50 Bath and Body Works $1.30 $10 Derry Auto (c.o.a.) $5.00 $100 Bath and Body Works $3.25 $25 Dillard’s $2.25 $25 Bed, Bath and Beyond $1.75 $25 Dress Barn $2.00 $25 Best Buy $0.50 $25 Express $2.50 $25 Best Buy $2.00 $100 Fareway $0.50 $25 Big Time Cinema (Fridley’s) $1.00 $10 Fareway $1.00 $50 Borders/Waldenbooks $0.90 $10 Fareway $2.00 $100 Borders/Waldenbooks $2.25 $25 Fairfield Inn/Marriott $6.00 $50 Build-A-Bear $2.00 $25 Fazoli’s $1.75 $25 Burger King $0.50 $10 Finish Line $2.50 $25 Cabela’s $3.25 $25 Flower Cart (c.o.a.) $1.25 $25 Carlos O’Kelly $0.90 $10 Foot Locker $2.25 $25 Casey’s $0.30 $10 Fuhs Pastry $1.00 $10 Casey’s $0.75 $25 Gap/Old $2.25 $25 Navy/Banana Republic Casey’s $1.50 $50 GameStop $0.75 $25 Cheesecake Factory $1.25 $25 Gerber’s (c.o.a.) $2.50 $50 Chili’s/Macaroni Grill/On the $2.75 $25 Gerber’s (c.o.a.) $5.00 $100 Boarder Chuck E. -

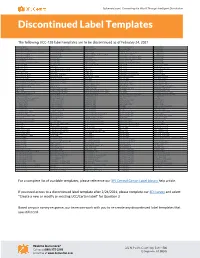

Discontinued Label Templates

3plcentral.com | Connecting the World Through Intelligent Distribution Discontinued Label Templates The following UCC-128 label templates are to be discontinued as of February 24, 2021. AC Moore 10913 Department of Defense 13318 Jet.com 14230 Office Max Retail 6912 Sears RIM 3016 Ace Hardware 1805 Department of Defense 13319 Joann Stores 13117 Officeworks 13521 Sears RIM 3017 Adorama Camera 14525 Designer Eyes 14126 Journeys 11812 Olly Shoes 4515 Sears RIM 3018 Advance Stores Company Incorporated 15231 Dick Smith 13624 Journeys 11813 New York and Company 13114 Sears RIM 3019 Amazon Europe 15225 Dick Smith 13625 Kids R Us 13518 Harris Teeter 13519 Olympia Sports 3305 Sears RIM 3020 Amazon Europe 15226 Disney Parks 2806 Kids R Us 6412 Orchard Brands All Divisions 13651 Sears RIM 3105 Amazon Warehouse 13648 Do It Best 1905 Kmart 5713 Orchard Brands All Divisions 13652 Sears RIM 3206 Anaconda 13626 Do It Best 1906 Kmart Australia 15627 Orchard Supply 1705 Sears RIM 3306 Associated Hygienic Products 12812 Dot Foods 15125 Lamps Plus 13650 Orchard Supply Hardware 13115 Sears RIM 3308 ATTMobility 10012 Dress Barn 13215 Leslies Poolmart 3205 Orgill 12214 Shoe Sensation 13316 ATTMobility 10212 DSW 12912 Lids 12612 Orgill 12215 ShopKo 9916 ATTMobility 10213 Eastern Mountain Sports 13219 Lids 12614 Orgill 12216 Shoppers Drug Mart 4912 Auto Zone 1703 Eastern Mountain Sports 13220 LL Bean 1702 Orgill 12217 Spencers 6513 B and H Photo 5812 eBags 9612 Loblaw 4511 Overwaitea Foods Group 6712 Spencers 7112 Backcountry.com 10712 ELLETT BROTHERS 13514 Loblaw -

FOR LEASE WHITTIER MEDICAL BUILDING 15141 Whittier Blvd, Whittier, CA 90603

FOR LEASE WHITTIER MEDICAL BUILDING 15141 Whittier Blvd, Whittier, CA 90603 Class A Medical Office Building LOCATION! JAIRO JAY GAMBA LOCATION! Commercial Specialist Direct: 818-624-8013 LOCATION! BRE # 01945027 BUILDING HIGHLIGHTS •Unique opportunity to Lease one of the newly renovated Medical Office Buildings, “Class A” •Property is strategically located on camps of Whittier Hospital Medical Center with approximately 500 physicians, and over 40 specialties, 178 bed facility, surrounded by Retail including Trader Joe’s, HomeGoods, Sears, Ralph’s, OfficeMax, US Post Office, KOHL’S, Wells Fargo, Bank of America, Bank of California, Bank of Wittier, Starbucks, Restaur17nts, Transportation, and more. •Prestige Tenants on site such as Whittier Hospital, Urgent Care, Dentists, and Specialty Doctors •Space available from 902 SF to 5,632 SF, maximum contiguous space 6,863 SF, and over 800 on-site parking spots. ACT NOW! JAIRO JAY GAMBA Cell: 818.624.8013 700 S. Flower St., Suite 2900, Los Angeles, CA 90017 Email: [email protected]| Website: www.LALiveProperties.com PROPERTY DESCRIPTION HIGHLIGHTS KW DTLA and LA LIVE PROPERTIES are pleased to present a Unique Opportunity to lease one of the newly renovated Medical office buildings with quality, LONG TERM tenants in the business-friendly, up and coming city of Whittier. Tenants include: Whittier Hospital Medical Center, Bank of Whittier, Outpatient Surgery, Medical doctors, Quest Diagnostics Lab, accounting office, financial institutions and more. Ready to move in medical and general office space available. Class A, five story Building offer a maximum contiguous space of 6,863 SF of attractive/remodeled Office-Medical space units with tenant improvements from 902 SF to 5,632 SF, and on-site parking. -

![Allstate Ins. Co. V. Sears, 2007-Ohio-4977.] STATE of OHIO, BELMONT COUNTY](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7861/allstate-ins-co-v-sears-2007-ohio-4977-state-of-ohio-belmont-county-1757861.webp)

Allstate Ins. Co. V. Sears, 2007-Ohio-4977.] STATE of OHIO, BELMONT COUNTY

[Cite as Allstate Ins. Co. v. Sears, 2007-Ohio-4977.] STATE OF OHIO, BELMONT COUNTY IN THE COURT OF APPEALS SEVENTH DISTRICT ALLSTATE INSURANCE COMPANY ) CASE NO. 06 BE 10 ) PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT ) ) VS. ) OPINION ) SEARS ROEBUCK AND CO. ) ) DEFENDANT-APPELLEE ) CHARACTER OF PROCEEDINGS: Civil Appeal from the Court of Common Pleas of Belmont County, Ohio Case Nos. 03 CV 0348; 05 CV 0018 JUDGMENT: Affirmed. APPEARANCES: For Plaintiff-Appellant: Atty. Brian Green Atty. Karen Burke Shapero & Green LLC Signature Square II, Suite 220 25101 Chagrin Boulevard Beachwood, Ohio 44122 For Defendant-Appellee: Atty. Matthew K. Seeley Atty. Keith A. Savidge Seeley, Savidge & Ebert Co., LPA Fifth Third Center 600 Superior Avenue, East-Suite 800 Cleveland, Ohio 44114 JUDGES: Hon. Cheryl L. Waite Hon. Gene Donofrio Hon. Mary DeGenaro Dated: September 20, 2007 [Cite as Allstate Ins. Co. v. Sears, 2007-Ohio-4977.] WAITE, J. {¶1} On January 15, 2003, a fire occurred at Janet E. Shaver’s residence in Bellaire, Ohio. Janet was renting the house from her mother, Betty Shaver. The house was heated by an oil furnace, which was sold and serviced by Sears Roebuck and Co. Appellant, Allstate Insurance Company, had issued a comprehensive renters’ policy of insurance to Janet. Allstate paid Janet the benefits of her policy minus her deductible in the amount of $80,397.14. {¶2} On September 18, 2003, Allstate filed suit against Appellee, Sears, in the Belmont County Court of Common Pleas. Allstate claimed that it was subrogated to Janet’s rights, and it sought the return of its payment to Janet. -

A Postmortem for Sears - Transcript

A Postmortem for Sears - Transcript Tom Mullooly: In episode 123, we're going to do a postmortem on Sears Roebuck. Stick around. Welcome to the Mullooly Asset show. I'm your host, Tom Mullooly, and this is episode number 123. One, two, three red light. So today, the day that we're recording this, it looks like Sears Roebuck is going to ask the bankruptcy court to enter liquidation, and that's the end of Sears as we know it. So I thought it would be a good time to just kind of take a walk down memory lane. There's a lot of people in the media today who are comparing Amazon to Sears saying, "Hey, Sears was the Amazon of its day." And I just want to share a couple of things that I've learned over the years about Sears. It was started in 1886 as a mail order company. Richard Sears actually sold watches through a catalog that he put together. A year later, in 1887, he hires a guy named Alvah Roebuck to repair watches. So I guess they had problems with some of the watches that they were selling through their catalog. They then added jewelry, and the mail order business really took off. What helped them, a little bit of history for you, is that in the late 1880s, the US government started a program called rural free delivery, or RFD. Some of you are around my age may remember a TV show after Andy Griffith left. It was called Mayberry RFD, and everybody always wanted to know what RFD stood for. -

Why Lands' End?

WHY LANDS’ END? • We are America’s premier school uniform provider, helping millions of students get ready for school. • With our School Rewards Program, Preferred Schools can earn up to 6% back on your school’s uniform purchases for the year. • We offer a full range of sizes – grades pre-K to 12 – to fit every student, including regular, extended sizes, juniors, young men, husky, tall, slim and more. • We provide quality products built to last, so that means a lower replacement cost for your parents. • We offer a custom online shopping experience for your school, to make ordering quick and easy (along with safe and secure) for your parents. • Our legendary customer service gives your parents a great shopping experience with every order. 24 hours a day, 364 days a year (we are closed Christmas Day), you can speak to a live Lands’ End® employee. • Returns can be made at any U.S. Sears store where Lands’ End is sold with no restocking charge, and replacement orders are shipped free. • We offer free hemming on unfinished girls’ and boys’ pants. • We will provide a specialized account team dedicated to your school with full knowledge of your dress code and any other specific needs. • We handle the inventory, so there’s no investment required for your school. No minimums, no risk. • Guaranteed. Period.® Our rock-solid promise of satisfaction. Returns are always accepted for any reason, regardless of whether the product has been washed, worn, or logo’d. 1-800-741-6311 | LANDSEND.COM/SCHOOL SCHOOL UNIFORMS DEMAND UNIFORM COLORS. -

Paper Procurement Policy

SEARS HOLDINGS CORPORATION’S SUSTAINABLE PAPER PROCUREMENT POLICY Our Commitments Sears Holdings Corporation and its affiliates, including Sears Roebuck and Co. and Kmart Corporation ("SHC") are committed to having a positive role in promoting the sustainability of forests and other natural resources. The objective of this policy is to encourage a sustainable combination of resources and processes to produce the paper for: • catalogs and retail flyers/circulars • internal use • direct mail Sustainable Fiber SHC will not knowingly source fiber from illegally harvested or traded sources. Our goal is to procure paper sourced from credibly certified forest sources with verified chain-of-custody. We use principles of lifecycle assessment to comparatively rate the environmental impact of paper procurement choices. In practice, this means working with our suppliers to get more accurate understandings of the lifecycle costs of paper choices based on grade types and fiber sources available. Supplier Requirements and Preferred Sustainable Supplier Program We require all of our paper suppliers to meet our supplier requirements. By meeting those requirements and going beyond them, suppliers can also qualify for our preferred sustainable supplier program. The preferred program gives purchasing preference to suppliers who otherwise meet our price, reliability and quality requirements. Supplier Requirements All paper suppliers to SHC must ensure that their products are legally harvested and traded. Paper suppliers to SHC are not permitted to provide paper from "unwanted" forest sources. An Unwanted Source falls within one or more of the following categories: • The source forest is known or suspected of containing high conservation values, except where: o The forest is certified or in progress of certification under a credible certification standard ensuring responsible management practices, or o The forest manager can otherwise demonstrate that the forest and/or surrounding landscape is managed to ensure those values are maintained. -

Contains Important Information About Your Sears Holdings Benefits

SHC Active Associates (US and Puerto Rico) December, 2017 To Sears Holdings Associates: Included is the following information about your benefits: Item Page Explanation This report provides a summary of the most recent annual report filed with the Employee Benefits Security Administration for the listed plans. This report is required to be given to each benefit plan participant in accordance with federal Summary Annual Report 2-4 regulations. To simplify the distribution, each benefit plan is included in the report; though you yourself may not be eligible for or enrolled in each of these plans at this time. Employee Welfare Benefit Plan: This notice provides a summary of changes to the Sears Holdings Medical Notice of Changes to the Medical Plan 4-5 Plan that will become effective on January 1, 2018. Employee Welfare Benefit Plan: This notice provides a summary of changes to the Sears Holdings Long Term Notice of Changes to the Long Term Disability 5 Disability Plan that became effective on July 1, 2017. Plan This notice provides a summary of changes to the Sears Holdings Flexible Notice of Changes to the Flexible Benefits Plan 5 Benefits Plan that will become effective on January 1, 2018. This notice summarizes certain changes to the Savings Plan that became Notice of Changes to the Savings Plan 6 effective in 2017 or will take effect in 2018, including updates to the 2018 annual contribution limits specified by the U.S. Internal Revenue Code. Enrollment Reminder: This is an enrollment reminder regarding the Associate Stock Purchase Plan. 6 Associate Stock Purchase Plan This notice describes the relevant CHIP provisions and lists contact Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) 7-9 information for the states whose CHIP or Medicaid programs offer premium Notification assistance. -

291550 Berlyfcneowtsyq9tmq

SEARS Corporate Branding Guide, 2009 Executive Edition © Sears Holding Corp. Designed by EyeCon Graphics .......................................................................Our Mission .......................................................................................Our Story .........................................................................Current Brand .............................................................................Why Rebrand? ......................................................Mood and Inspiration ..............................................................................Color Choice The Guide .........................................................................................Type .........................................................................Imagery ................................................................................Logo Design .....................................................................Internal Launch ...........................................................................Employee Gifts ...........................................................................Stationery ..............................................................................The Campaign ....................................................................The New Look Mission To grow our business by providing quality products and services at great value when and where our customers want them, and by building positive, lasting relationships with our customers. Sears’ Vision To be the preferred -

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS of MAJOR US RETAILERS BASED on ENTERPRISE MARKETING EFFICIENCY Ramon Corona, National University

GLOBAL JOURNAL OF BUSINESS RESEARCH ♦ VOLUME 8 ♦ NUMBER 4 ♦ 2014 A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF MAJOR US RETAILERS BASED ON ENTERPRISE MARKETING EFFICIENCY Ramon Corona, National University ABSTRACT The purpose of this research was to analyze financial results of four major US retailers from June 2006 until August 2008 and compare their tactics to create shareholder’s value, using key performance and enterprise marketing ratios. This is a relevant study given the different business models and strategies used by these companies, as well as their strong rivalry in the retail industry. The study highlighted Walmart and Costco given their recent growth and competitiveness. The results showed that Walmart was superior in attracting investors willing to pay a premium for the stock. On the other hand, Costco created an average of $10.32 dollars of sales for every dollar spent in Sales, General and Administrative expenses, whereas Walmart produced only $5.44. In other words, Costco created twice as much sales volume for every dollar spent in these expenses. Further, the Maximum Earnings Market Share displayed that Costco could have made $3,660 million more in that period, whereas Walmart spent $26,300 million more than needed to increase earnings in the same period. JEL: M2, M3, G1 KEYWORDS: Marketing, Enterprise Marketing, Market Value, Efficiency, Market Share, Costco, Walmart, Retail Industry INTRODUCTION he purpose of this research is to analyze the four major retailers in the United States, including Sears, Target, Walmart and Costco in the ten quarters from June 2006 until August 2008 considering their T use of money to create shareholder’s value, calculated on key performance and enterprise marketing ratios.