Figurations of Adolescence on the Late Twentieth-Century Stage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2011 – Cincinnati, OH

Society for American Music Thirty-Seventh Annual Conference International Association for the Study of Popular Music, U.S. Branch Time Keeps On Slipping: Popular Music Histories Hosted by the College-Conservatory of Music University of Cincinnati Hilton Cincinnati Netherland Plaza 9–13 March 2011 Cincinnati, Ohio Mission of the Society for American Music he mission of the Society for American Music Tis to stimulate the appreciation, performance, creation, and study of American musics of all eras and in all their diversity, including the full range of activities and institutions associated with these musics throughout the world. ounded and first named in honor of Oscar Sonneck (1873–1928), early Chief of the Library of Congress Music Division and the F pioneer scholar of American music, the Society for American Music is a constituent member of the American Council of Learned Societies. It is designated as a tax-exempt organization, 501(c)(3), by the Internal Revenue Service. Conferences held each year in the early spring give members the opportunity to share information and ideas, to hear performances, and to enjoy the company of others with similar interests. The Society publishes three periodicals. The Journal of the Society for American Music, a quarterly journal, is published for the Society by Cambridge University Press. Contents are chosen through review by a distinguished editorial advisory board representing the many subjects and professions within the field of American music.The Society for American Music Bulletin is published three times yearly and provides a timely and informal means by which members communicate with each other. The annual Directory provides a list of members, their postal and email addresses, and telephone and fax numbers. -

Coventry & Warwickshire Cover

Worcestershire Cover April 2018.qxp_Worcestershire Cover 23/03/2018 14:06 Page 1 Your FREE essential entertainment guide for the Midlands WICKED RETURNS TO THE MIDLANDS WORCESTERSHIRE WHAT’S ON APRIL 2018 ON APRIL WHAT’S WORCESTERSHIRE Worcestershire ISSUE 388 APRIL 2018 ’ WhatFILM I COMEDY I THEATRE I GIGS I VISUAL ARTS I EVENTSs I FOOD On worcestershirewhatson.co.uk PART OF WHAT’S ON MEDIA GROUP GROUP MEDIA ON WHAT’S OF PART inside: Yourthe 16-pagelist week by week listings guide THE LITTLE UNSAID rock, folk, electronica, jazz and alt-pop at The Marr’s Bar TWITTER: @WHATSONWORCS @WHATSONWORCS TWITTER: HARRY STYLES One Direction star goes it alone at the Genting Arena FACEBOOK: @WHATSONWORCESTERSHIRE FAST AND FURIOUS stunts, special effects and 3D WORCESTERSHIREWHATSON.CO.UK projections at the Arena... (IFC) Worcestershire.qxp_Layout 1 23/03/2018 15:10 Page 1 Contents April Warwicks_Worcs.qxp_Layout 1 22/03/2018 14:33 Page 2 April 2018 Contents Bollywood farce - Nigel Planer’s The Game Of Love & Chai opens at the Belgrade - feature page 8 Martine McCutcheon Wicked Romeo And Juliet the list the Love Actually star Lost hit musical returns to cast its brand new RSC staging of the your 16-page And Found at The Core spell over Midlands audiences world’s most famous love story week-by-week listings guide page 17 feature page 22 page 24 page 51 inside: 4. First Word 11. Food 17. Music 20. Comedy 24. Theatre 35. Film 40. Visual Arts 43. Events fb.com/whatsonwarwickshire fb.com/whatsonworcestershire @whatsonwarwicks @whatsonworcs Warwickshire -

Princes Theatre Princes Theatre

PRINCES THEATRE TOWN HALL, CLACTON-ON-SEA WHAT’S ON GUIDE SPRING 2017 WELCOME... Firstly, I would like to take this opportunity If you enjoyed Irelands Call and Essence For the family we are looking forward to a to wish all our customers a very Happy New of Ireland then Seven Drunken Nights is brand new show Marty MacDonald’s Toy Year and welcome you to another fantastic the show for you. Produced by the same Machine which is a fun, interactive, song- season at the Princes Theatre! production company Seven Drunken Nights filled adventure, featuring a host of lovable We didn’t think it was possible to top brings to life the music of puppet characters plus CBeebies’ Justin the success of 2015 but wow what a Ireland’s favourite sons – Fletcher is the voice of Pongo the Pig. phenomenal year 2016 turned out to be. ‘The Dubliners’. We finish off the season with a We had an impressive 130 shows/events Following his successful tour family extravaganza, this year’s Easter during the year including our first ever from last year we are pleased Pantomime Robin Hood starring Gareth Monsters Ball which was a huge success. to have back by popular demand Pasha Gates, Graham Cole and Zippy and George We also held 4 Boxing Events, 2 Wedding whose special guest is Anya Garnis with from children’s television show Rainbow. If Fairs, 5 Weddings and 3 award ceremonies. their brand new tour “Let’s Dance the Night you came to see last year’s Beauty and the The continuous growth of our theatre has Beast you know you will be in for a real treat. -

Box Office 0121 704 6962

SPRING 2017 BOX OFFICE 0121 704 6962 6 GE thecoretheatresolihull.co.uk EE PA UR - S KING ARTH WELCOME! TO THE CORE What a year! We started 2016 being refurbished and month by month we revealed our bright new facilities to both our loyal audiences and new attenders. Some new users may never have stepped into our theatre, had they not been visiting another area of The Core, which is Solihull’s flagship community building. We’ve all settled in well together and new partnerships are being forged all around The Core for the benefits of all our users. Finally, after 20+ years as Solihull Arts Complex, we changed our name and became known as The Core Theatre Solihull! This meant new uniform, new designs and lots of forgetting who we are when answering phones! COUR What doesn’t change is the warm friendly welcome we offer at The Core TYA RD Theatre, in Encore Cafe, at Box Office and at the host of activities and classes we offer G A LL throughout the year. E R With the completion of the Courtyard Gallery our Exhibitions Diary is filling up fast Y (see back cover) and 2017 will bring new opportunities to take part or learn something new. If you have any suggestions for something you’d like to try, and think others might too, from coding to crochet… don’t sit on your idea, please tell us! Email your ideas to: [email protected] Finally, theatre tickets or vouchers are always popular but the big hit of the Autumn has been our scrumptious Cream Teas. -

Robin Windsor & Mila Lazar

ROBIN WINDSOR & MILA LAZAR 29TH MAY TO 12TH JUNE 2016 YOUR HOSTS MILA LAZAR Mila started her career as a professional dancer ROBIN WINDSOR in Germany at the Cranko Ballet school in Stuttgart. She performed in musicals such Robin’s dance genesis was initiated by his as “A Chorus Line” & “ My Sweet Charity”. parents when at the age of three they enrolled She was hand picked by the Master of Jazz him in a local dance school in Ipswich, England. dance, Gus Giordano at a workshop and From the very beginning, Robin studied both he invited her to join the Gus Giordano Dance Ballroom and Latin dance eventually competing Company as an apprentice at the Chicago school. in those disciplines at the highest levels. His skills eventually led him to represent England, After a successful year there, she moved to The Netherlands to amassing numerous World Championships, both on the domestic study for her classical ballet & contemporary dance degree at the and international level. Hooge school voor de kunsten (Dance Academy) in Arnhem. To be able to support her studies Mila instucted Aerobics, Step, Street In 2000 Robin was cast in the immensely popular and critically Dance and Body Conditioning at a local sports club. acclaimed dance company Burn the Floor. He continued his remarkable career with Burn the Floor for nine years which included During her last year of study, Mila attended an audition that two world tours (2003/2004). The Company developed a new changed her life. She joined the Girl band “Alice Deejay”, know show, FloorPlay where he enjoyed a leading role as well as another world-wide for hits like “ Better off Alone” and“Back in my life”. -

Strictly Come Dancing Premieres on Uktv in January 2014

12 December 2013 STRICTLY COME DANCING PREMIERES ON UKTV IN JANUARY 2014 PUTTING THE SPARKLE INTO WEDNESDAY & THURSDAY EVENINGS FIRST ON FOXTEL One of the biggest shows on British television - Strictly Come Dancing is premiering on UKTV on Wednesday, January 1 at 8:30pm, with series 11 bringing an all-star line-up of celebrities with more sparkle, sizzle and glitz than ever before. 15 celebrities take on the challenge of perfecting the art of ballroom and Latin dancing under the tutelage of 15 phenomenally talented professional dancers at the top of their game. Celebrities joining the ranks include multi-platinum selling singer/songwriter, model and DJ Sophie Ellis-Bextor; former Coronation Street baddie Natalie Gumede; Rugby World Cup champion Ben Cohen; queen of the runway and TV presenter Abbey Clancy; Hollyoaks hunk Ashley Taylor Dawson; one half of the Hairy Bikers Dave Myers; British multi-millionairess Deborah Meaden; Strictly’s very first fashion designer, Julien Macdonald; actor Mark Benton; Casualty star Patrick Robinson; television presenter Rachel Riley; journalist and presenter Susanna Reid; sporting legend Tony Jacklin CBE and finally TV presenter, broadcaster and journalist Vanessa Feltz. Judges are Len Goodman, Craig Revel Horwood, Bruno Tonioli and Darcey Bussell. Reaching a series high of 11.7 million viewers in the UK, Australian viewers will be dazzled with two episodes to look forward to each week. To kick things off, UKTV will screen the Performance Show every Wednesday at 8:30pm, hosted by television presenters Sir Bruce Forsyth and Tess Daly. Joining Tess on Thursday evenings at 8:30pm is television and radio presenter Claudia Winkleman to present the Results Show where the couple with the lowest combined scores will face each other in the all-important dance off, with one couple leaving the competition for good. -

COMES to the PAVILION THIS SPRING! Welcome to Exmouth Pavilion

Spring 2018 Programme ‘STRICTLY’ COMES TO THE PAVILION THIS SPRING! Welcome to Exmouth Pavilion Exmouth Pavilion is an outstanding entertainment The Café and Bar is open every day from 9am if you venue directly on the seafront in Exmouth. Over would like to just stop for a coffee and a cake, we Sinbad & the Seaman – the course of the year we have welcomed around can also offer light snacks and main meals, all of Adult Panto Spring 2018 100,000 visitors to everything from Pantomime, which is top quality local produce. Friendly dogs are touring productions, rock concerts and classical also welcome. Directly opposite is the private car Friday 26th January – 7.30pm music, dance, Charity and fundraising events, to park where you are able to park for free when using Hot on the heels of last year’s Adult Panto - our free entertainment in the Exmouth Pavilion our facilities, we have excellent disabled level gardens, and our regular comedy evenings and access too. PUSS & DICK - the Market Theatre Company weekly Cash Bingo! return to bring to life the story of Sinbad the There is always a great deal going on at the Sailor and his epic adventures across the From time to time we have concessions available Exmouth Pavilion. For exclusive offers and news as seas to defeat the one-eyed monster and for some shows, including Early Bird incentives it happens, check the website: packing it with corny jokes, raunchy plots and Special Promotions. Please ask at the time of www.ledleisure.co.uk/exmouth-pavilion and blatant sexual innuendo! purchasing your tickets if a concession is available to you. -

What's on at the Brunton Apr–Jul 18

The Brunton, Ladywell Way, Musselburgh EH21 6AA Tickets: thebrunton.co.uk / 0131 665 2240 WHAT’S ON AT THE BRUNTON APR–JUL 18 The place to be in East Lothian Our live theatre and opera screenings are going down a storm so we are delighted to host in May, a cinema broadcast of Matthew Bourne’s Cinderella, followed by a Q&A streamed live, with Matthew Bourne himself. This is a unique addition just for the cinema screening. Thanks to our Creative Scotland funding we have handpicked a selection of inspiring classical music concerts for you, with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Susan Tomes’ Lecture Recital and Lucy Parham’s Elégie Rachmaninoff - A Heart in Exile a portrait of the composer in music and words, with actor Tim McInnerny. CS funding also supports our theatre and dance programme, allowing us to provide high quality arts experiences at The Brunton. This spring you can enjoy The Monster and Mary Shelley from Scottish theatre company The Occasion, The Isle of Love – musical theatre set on a Hebridean Island from Right Moves and much more! There is laughter in the air this spring at The Brunton! TV favourite Dad’s Army comes to life in Dad’s Army Radio Hour; veteran comedians Tommy Cannon and Crissy Rock entertain in Seriously Dead and Andy Gray and Grant Stott are a must see with Double Feature. There’s a fantastic buzz at The Brunton at this time of year as our Youth Theatre Network and Move It! dance classes take to the stage with their showcases of what they have achieved over the year. -

| Palo Alto Online |

Palo Vol. XXIX, Number 57 • Wednesday, April 23, 2008 ■ 50¢ Alto Who will pay for sidewalk repair? Page 3 www.PaloAltoOnline.comw ww.PaloAltoO nline.com Reinventing grad school Grants create intellectual, social community at Stanford Page 3 Photo Illustration Susan Bradley/Carol Hubenthal Explore our new real estate Web site at www.PaloAltoOnline.com/real_estate ■ Upfront Future of Internet debated at Stanford Page 3 ■ Neighborhoods Barron Park battles May Fete ‘volunteer fatigue’ Page 7 ■ Sports Stanford baseball sits at top of PAC-10 standings Page 30 apr.com It's just one click to a complete list of virtually all homes for sale in the Bay Area. LOS ALTOS HILLS Amazing hilltop custom- designed home surrounded by breathtaking views. Step- down living/dining room with fireplace. Eat-in kitchen with floor to ceiling windows. Hardwood floors. Perfect patio for outdoor living and entertaining. $2,668,000 PALO ALTO This exquisitely-designed 4 bedroom, 3.5 bath French-style home offers charm and high-end appointments. Rich detailing, hardwood floors, high coffered ceilings, gourmet kitchen with Thermador appliances. $2,250,000 MENLO PARK Suburban Park 3bd/2ba sunny and bright home with updated kitchen featuring Corian counters and greenhouse window. Hardwood floors. Living room with fireplace, separate dining area. Updated master bath. $789,000 apr.com | PALO ALTO OFFICE 578 University Avenue 650.323.1111 APR COUNTIES | Santa Clara | San Mateo | San Francisco | Alameda | Contra Costa | Monterey | Santa Cruz Page 2 • Wednesday, April 23, 2008 • Palo Alto Weekly UpfrontLocal news, information and analysis Plan to share sidewalk-repair costs curbed? If dropped, financing of proposed public-safety proposal made him “squirm”; coun- do it this way, but that doesn’t mean don’t necessarily use the sidewalks cil members Yoriko Kishimoto and we should do it,” Klein said. -

1. Front Page 1 Layout 1

After 35 years, The Bronx closes The Melrose purchases iconic restaurant Owners of the gayborhood institution look forward • DINING, Page 24 DallasVoice.com DallasVoice.com/Instant-Tea Facebook.com/DallasVoice Twitter.com/DallasVoice The Premier Media Source for LGBT Texas Established 1984 | Volume 27 | Issue 46 FREE | Friday, April 1, 2011 DFW Sisters bring the outrageous fun A Sister Act and dedicated activism of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence to North Texas Read the full story beginning on Page 13 2 dallasvoice.com • 04.01.11 toc04.01.11 | Volume 27 | Issue 46 9 headlines • TEXAS NEWS 4 Fort Worth AIDS walk is Sunday 4 Incumbents campaign for re-election 8 Black Tie announces beneficiaries 9 Chamber honors members at dinner • LIFE+STYLE 23 BoyGush keeps chat on the Web 23 24 The Bronx closes after 35 years 26 Britney and REM release new CDs 28 ‘Burn’ stars out ballroom champ COVER PHOTO Members of the Dallas Sisters include, front row, left to right: Post. Shahira Lotta Voicez, NvSr Amanda DeFlower, NvSr Kerianna Kross; middle row, left to right: Post. Fondalyn Grope, Post. Plenty O'Cleavage, Post. Thumb Belina; back row, left to right : NvSr Bertha Sinn, NvSr Eve Angelica, NvSr Tasha myFUPA. Photo courtesy Dallas Sisters. Cover design by Michael Stephens. 26 departments 4 Texas News 20 Life+Style 6 Pet of the Week 34 Starvoice 8 Weddings 36 Scene 18 Viewpoints 38 Classifieds 04.01.11 • dallasvoice 3 • texasnews instantTEA DallasVoice.com/Instant-Tea Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson: Crowe ‘never met a stranger’ Making a better world, -

Pasha Kovalev

191 Wardour Street London W1F 8ZE Phone: 020 7439 3270 Email: [email protected] Website: www.olivia-bell.co.uk Pasha Kovalev Pasha Kovalev was born in Siberia and started dancing at the age of eight. He competed in the US series So You Think You Can Dance after going along to the auditions to help out his then dance partner Anya Garnis. The producers were so impressed they took him on the show where he became a firm favourite. Following his success he toured the world in the legendary dance show Burn The Floor before he was offered a place on BBC1 Strictly Come Dancing and moved to the UK in 2011 to join the professional team. Since then he has competed in eight series, winning in 2014 with TV Presenter Caroline Flack. He still holds the accolade of having more number 10s than any other pro-dancer! He has directed, choreographed and produced his own UK tours for 7 years, toured with The Strictly Live Tour and last year The Professionals Tour which paid a tribute to him as he announced he was standing down from the BBC series. He has also appeared on The Greatest Dancer, released his autobiography and appeared twice on Channel 4 Countdown alongside his wife, Rachel Riley. He can also be seen on The Strictly Cruises. In 2021, Pasha is due to join the West End Cast of Here Come The Boys at the Garrick Theatre. Powered by Tagmin Every effort has been made to make sure that the information contained in this page is correct and Tagmin can accept no responsibility for its accuracy. -

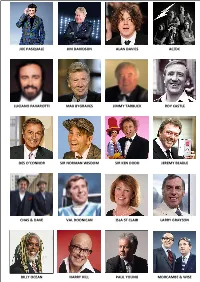

Joe Pasquale Jim Davidson Max Bygraves Jimmy Tarbuck

JOE PASQUALE JIM DAVIDSON ALAN DAVIES AC/DC LUCIANO PAVAROTTI MAX BYGRAVES JIMMY TARBUCK ROY CASTLE DES O’CONNOR SIR NORMAN WISDOM SIR KEN DODD JEREMY BEADLE CHAS & DAVE VAL DOONICAN ISLA ST CLAIR LARRY GRAYSON BILLY OCEAN HARRY HILL PAUL YOUNG MORCAMBE & WISE THE TREORCHY CHOIR ALEX HIGGINS GERRY MARSDEN DAVE DEE SUZI QUATRO RAY ALAN NORMAN COLLIER FRANK CARSON THE COMMITMENTS BOBBY KNUTT CILLA BLACK BARBARA WINDSOR DAVE BERRY FREDDIE STARR THE SUPREMES JIMMY WHITE RONNIE O’SULLIVAN STAN BOARDMAN FRANKIE VAUGHAN JIMMY GREAVES KATHY KIRBY ALVIN STARDUST THE TROGGS JASPER CARROTT BEV BEVAN THE HOLLIES MIKE YARWOOD MOTÖRHEAD SIR BOB GELDOF THE DRIFTERS ROY ‘CHUBBY’ BROWN RHOD GILBERT VICTORIA WOOD JIMMY CRICKET BERT WEEDON JOE LOSS CHUCKLE BROTHERS SOOTY DICKIE HENDERSON BOB MONKHOUSE RICK WAKEMAN MARTY WILDE THE STYLISTICS JIMMY CARR PADDY McGUINNESS MATTHEW FORD DAVE ALLEN STEVE DAVIS MARTI CAINE NEW AMEN CORNER STEVE BEATON JAKE THACKRAY DICK EMERY ED BYRNE DENNIS LOTIS FRED DIBNAH RUSSELL WATSON BILL HALEY THE PLATTERS WHITESNAKE HUMPHREY LYTTLETON BILL MAYNARD DAVID NIXON HENRY BLOFELD SHAKIN’ STEVENS SUSIE BLAKE KATE ROBBINS EDWIN STARR JET HARRIS ARTHUR BOSTROM DR FEELGOOD MICK MILLER GIANT HAYSTACKS GEORGE HAMILTON IV DEBBIE McGEE PAUL DANIELS MARTHA REEVES WENDY PETERS SHOWADDYWADDY DAVID DICKINSON ASWAD RAY QUINN THE BEVERLEY SISTERS STU FRANCIS CRISSY ROCK SIMON RATTLE TED HEATH THE ROCKIN’ BERRIES DEL SHANNON HEAVY METAL KIDS CHRIS RAMSEY BRIAN BLESSED DON MACLEAN FOSTER & ALLEN JUDAS PRIEST ERIC DELANEY PAM AYRES DAVID SHEPHERD