Summer Chronicle 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Limerick Timetables

Limerick B A For more information For online information please visit: locallinklimerick.ie Call us at: 069 78040 Email us at: [email protected] Ask your driver or other staff member for assistance Operated By: Local Link Limerick Fares: Adult Return/Single: €5.00/€3.00 Student & Child Return/Single: €3.00/€2.00 Adult Train Connector: €1.50 Student/Child Train Connector: €1.00 Multi Trip Adult/Child: €8.00/€5.00 Weekly Student/Child: €12.00 5 day Weekly Adult: €20.00 6 day Weekly Adult: €25.00 Free Travel Pass holders and children under 5 years travel free Our vehicles are wheelchair accessible Contents Route Page Ballyorgan – Ardpatrick – Kilmallock – Charleville – Doneraile 4 Newcastle West Service (via Glin & Shanagolden) 12 Charleville Child & Family Education Centre 20 Spa Road Kilfinane to Mitchelstown 21 Mountcollins to Newcastle West (via Dromtrasna) 23 Athea Shanagolden to Newcastle West Desmond complex 24 Castlemahon via Ballingarry to Newcastle West - Desmond Complex 25 Castlmahon to Newcastle West - Desmond Complex 26 Ballykenny to Newcastle West- Desmond Complex 27 Shanagolden to Newcastle West - Special Olympics 28 Tournafulla to Newcastle West - Special Olympics 29 Abbeyfeale to Newcastle West - Special Olympics 30 Elton to Hospital 31 Adare to Newcastle West 32 Kilfinny via Adare to Newcastle West 33 Feenagh via Ballingarry to Newcastle West - Desmond Complex 34 Knockane via Patrickswell to Dooradoyle 35 Knocklong to Dooradoyle 36 Rathkeale via Askeaton to Newcastle West to Desmond Complex 37 Ballingarry to -

Limerick Walking Trails

11. BALLYHOURA WAY 13. Darragh Hills & B F The Ballyhoura Way, which is a 90km way-marked trail, is part of the O’Sullivan Beara Trail. The Way stretches from C John’s Bridge in north Cork to Limerick Junction in County Tipperary, and is essentially a fairly short, easy, low-level Castlegale LOOP route. It’s a varied route which takes you through pastureland of the Golden Vale, along forest trails, driving paths Trailhead: Ballinaboola Woods Situated in the southwest region of Ireland, on the borders of counties Tipperary, Limerick and Cork, Ballyhoura and river bank, across the wooded Ballyhoura Mountains and through the Glen of Aherlow. Country is an area of undulating green pastures, woodlands, hills and mountains. The Darragh Hills, situated to the A Car Park, Ardpatrick, County southeast of Kilfinnane, offer pleasant walking through mixed broadleaf and conifer woodland with some heathland. Directions to trailhead Limerick C The Ballyhoura Way is best accessed at one of seven key trailheads, which provide information map boards and There are wonderful views of the rolling hills of the surrounding countryside with Galtymore in the distance. car parking. These are located reasonably close to other services and facilities, such as shops, accommodation, Services: Ardpatrick (4Km) D Directions to trailhead E restaurants and public transport. The trailheads are located as follows: Dist/Time: Knockduv Loop 5km/ From Kilmallock take the R512, follow past Ballingaddy Church and take the first turn to the left to the R517. Follow Trailhead 1 – John’s Bridge Ballinaboola 10km the R517 south to Kilfinnane. At the Cross Roads in Kilfinnane, turn right and continue on the R517. -

1911 Census, Co. Limerick Householder Index Surname Forename Townland Civil Parish Corresponding RC Parish

W - 1911 Census, Co. Limerick householder index Surname Forename Townland Civil Parish Corresponding RC Parish Wade Henry Turagh Tuogh Cappamore Wade John Cahernarry (Cripps) Cahernarry Donaghmore Wade Joseph Drombanny Cahernarry Donaghmore Wakely Ellen Creagh Street, Glin Kilfergus Glin Walker Arthur Rooskagh East Ardagh Ardagh Walker Catherine Blossomhill, Pt. of Rathkeale Rathkeale (Rural) Walker George Rooskagh East Ardagh Ardagh Walker Henry Askeaton Askeaton Askeaton Walker Mary Bishop Street, Newcastle Newcastle Newcastle West Walker Thomas Church Street, Newcastle Newcastle Newcastle West Walker William Adare Adare Adare Walker William F. Blackabbey Adare Adare Wall Daniel Clashganniff Kilmoylan Shanagolden Wall David Cloon and Commons Stradbally Castleconnell Wall Edmond Ballygubba South Tankardstown Kilmallock Wall Edward Aughinish East Robertstown Shanagolden Wall Edward Ballingarry Ballingarry Ballingarry Wall Ellen Aughinish East Robertstown Shanagolden Wall Ellen Ballynacourty Iveruss Askeaton Wall James Abbeyfeale Town Abbeyfeale Abbeyfeale Wall James Ballycullane St. Peter & Paul's Kilmallock Wall James Bruff Town Bruff Bruff Wall James Mundellihy Dromcolliher Drumcolliher, Broadford Wall Johanna Callohow Cloncrew Drumcollogher Wall John Aughalin Clonelty Knockderry Wall John Ballycormick Shanagolden Shanagolden & Foynes Wall John Ballygubba North Tankardstown Kilmallock Wall John Clashganniff Shanagolden Shanagolden & Foynes Wall John Ranahan Rathkeale Rathkeale Wall John Shanagolden Town Shanagolden Shanagolden & Foynes -

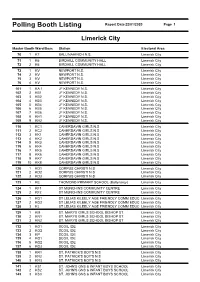

Polling Booth Listing Report Date 22/01/2020 Page 1

Polling Booth Listing Report Date 22/01/2020 Page 1 Limerick City Master Booth Ward/Desc Station Electoral Area 70 1 K7 BALLINAHINCH N.S. Limerick City 71 1 K6 BIRDHILL COMMUNITY HALL Limerick City 72 2 K6 BIRDHILL COMMUNITY HALL Limerick City 73 1 KV NEWPORT N.S. Limerick City 74 2 KV NEWPORT N.S. Limerick City 75 3 KV NEWPORT N.S. Limerick City 76 4 KV NEWPORT N.S. Limerick City 101 1 KA.1 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 102 2 KB1 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 103 3 KB2 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 104 4 KB3 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 105 5 KB4 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 106 6 KB5 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 107 7 KB6 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 108 8 KH1 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 109 9 KH2 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 110 1 KC1 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 111 2 KC2 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 112 3 KK1 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 113 4 KK2 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 114 5 KK3 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 115 6 KK4 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 116 7 KK5 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 117 8 KK6 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 118 9 KK7 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 119 10 KK8 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 120 1 KD1 CORPUS CHRISTI N.S Limerick City 121 2 KD2 CORPUS CHRISTI N.S Limerick City 122 3 KD3 CORPUS CHRISTI N.S Limerick City 123 1 KE THOMOND PRIMARY SCHOOL (Ballynanty) Limerick City 124 1 KF1 ST MUNCHINS COMMUNITY CENTRE Limerick City 125 2 KF2 ST MUNCHINS COMMUNITY CENTRE Limerick City 126 1 KG1 ST LELIAS KILEELY AGE FRIENDLY COMM EDUC Limerick City 127 2 KG2 ST LELIAS KILEELY AGE FRIENDLY COMM EDUC Limerick City 128 3 KJ ST LELIAS KILEELY AGE FRIENDLY COMM EDUC Limerick City 129 1 KM ST. -

Ahane, Castleconnell & Montpelier Community Plan the European

Ahane, Castleconnell & Montpelier Community Plan The European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development: Europe investing in rural areas Contents Foreword Introduction Executive Summary 1. The Planning Context pg 6 2. Demographic & Socio- Economic Profile pg 7 3. The Community Planning Process (the methodology) pg 19 4. The Three Workshops; Discussions & Outputs pg 20 5. Strategic Development Themes Emerging pg 33 6. Thematic Action Plan pg 36 7. Consultants Observations and Commentary pg 39 8. Appendices pg 40 Acknowledgements This Community Development Plan was funded by Ballyhoura Development CLG. The plan was prepared by the community, supported by staff of Ballyhoura Development and facilitated by Paul O Raw (O Raw Consultancy) & Associates, Niall Heenan and Dr Shane O Sullivan. The facilitators wish to acknowledge the support, guidance and enthusiasm invested by members of ACM Ltd and Love Castleconnell (host groups), local community groups and organisations, and local residents throughout this project. Thanks also to the full team of Ballyhoura Development staff, for their assistance and commitment through all stages of the project. 2 Page Ahane, Castleconnell, Montpelier Community Plan 2019-2023 Foreword – Ballyhoura Development For the past 30 years Ballyhoura Development has worked as the Community Led Local Development Company for North Cork and East Limerick. During this time Ballyhoura Development has believed in working with communities in this area and listening to their needs. The importance of community consultation has been paramount, and we have assisted communities to develop tailor made plans for the future of their own areas. Ballyhoura Development believe that a plan developed in this way, coming from the people themselves, is more sustainable and effective, and this is borne out through our work with the communities over almost 3 decades. -

LIMERICK Service Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Town County Registered Provider Telephone Number Service Type of Service

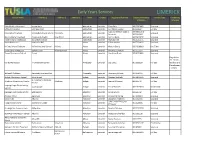

Early Years Services LIMERICK Service Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Town County Registered Provider Telephone Number Service Type of Service Little Buddies Preschool Knocknasna Abbeyfeale Limerick Clara Daly 085 7569865 Sessional Little Stars Creche Killarney Road Abbeyfeale Limerick Ann-Marie Huxley 068 30438 Full Day Meenkilly Pre School Meenkilly National school Meenkilly Abbeyfeale Limerick Sandra Broderick 087 9951614 Sessional Noreen Barry Playschool Community Centre New Street Abbeyfeale Limerick Noreen Barry 087 2499797 Sessional Teach Mhuire Montessori 12 Colbert Terrace Abbeyfeale Limerick Mary Barrett 086 3510775 Sessional Adare Playgroup Methodist Hall Adare Limerick Gillian Devery 085 7299151 Sessional Kilfinny School Childcare Kilfinny National School Kilfinny Adare Limerick Marion Geary 089 4196810 Part Time Little Gems Montessori Barley Grove Killarney Road Adare Limerick Veronica Coleman 087 9849022 Sessional Preschool Tuogh Montessori School Tuogh Adare Limerick Geraldine Norris 085 8250860 Sessional Full Day Part-time Karibu Montessori The Newtown Centre Annacotty Limerick Liza Eyres 061 338339 Sessional Full Day Part Time Wilmot's Childcare Annacotty Business Park Annacotty Limerick Rosemary Wilmot 061 358166 Sessional Ardagh Montessori School Main Street Ardagh Limerick Martina McGrath 087 6814335 Sessional Leaping Frogs Childminding Coolcappagh Ardagh Limerick Ann O'Donnell-Kelly 087 1514033 Childminder Service Full Day Part Time St. Colmans childcare services Kilcolman creche Kilcolman Ardagh Limerick Tara -

LIMERICK Service Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Town County Registered Provider Telephone Number Service Type Conditions of Service Attached

Early Years Services LIMERICK Service Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Town County Registered Provider Telephone Number Service Type Conditions of Service Attached Little Buddies Preschool Knocknasna Abbeyfeale Limerick Clara Daly 085 7569865 Sessional Little Stars Creche Killarney Road Abbeyfeale Limerick Ann-Marie Huxley 068 30438 Full Day Catriona Sheeran Sandra 087 9951614/ Meenkilly Pre School Meenkilly National school Meenkilly Abbeyfeale Limerick Sessional Broderick 0879849039 Noreen Barry Playschool Community Centre New Street Abbeyfeale Limerick Noreen Barry 087 2499797 Sessional Teach Mhuire Montessori 12 Colbert Terrace Abbeyfeale Limerick Mary Barrett 086 3510775 Sessional Adare Playgroup Methodist Hall Adare Limerick Gillian Devery 085 7299151 Sessional Kilfinny School Childcare Kilfinny National School Kilfinny Adare Limerick Marion Geary 089 4196810 Part Time Little Gems Montessori Barley Grove Killarney Road Adare Limerick Veronica Coleman 061 355354 Sessional Tuogh Montessori School Tuogh Adare Limerick Geraldine Norris 085 8250860 Sessional Regulation 19 - Health, Karibu Montessori The Newtown Centre Annacotty Limerick Liza Eyres 061 338339 Full Day Welfare and Developmen t of Child Wilmot's Childcare Annacotty Business Park Annacotty Limerick Rosemary Wilmot 061 358166 Full Day Ardagh Montessori School Main Street Ardagh Limerick Martina McGrath 087 6814335 Sessional St. Coleman’s Childcare Kilcolman Community Creche Kilcolman Ardagh Limerick Joanna O'Connor 069 60770 Full Day Service Leaping Frogs Childminding Coolcappagh -

341 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

341 bus time schedule & line map 341 Bilboa Cross stop 346231 - Shannon Ind Est stop View In Website Mode 336601 The 341 bus line (Bilboa Cross stop 346231 - Shannon Ind Est stop 336601) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Bilboa Cross (Bilboa Sports Grounds) - Element Six: 6:25 AM (2) Shannon Ind Est (Opp Ge Money) - Bilboa Cross (Opp Sports Grounds): 4:35 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 341 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 341 bus arriving. Direction: Bilboa Cross (Bilboa Sports Grounds) - 341 bus Time Schedule Element Six Bilboa Cross (Bilboa Sports Grounds) - Element Six 17 stops Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 6:25 AM Bilboa Cross Stop 346231 Tuesday 6:25 AM Stop No. 346191 Wednesday 6:25 AM Cappamore Stop 335131 Thursday 6:25 AM Drumsally Cross Stop 335121 Friday 6:25 AM Murroe Stop 335111 Saturday Not Operational Cappahana Cross Stop 335101 Newport Stop 335071 341 bus Info Direction: Bilboa Cross (Bilboa Sports Grounds) - Shower Cross Stop 335061 Element Six Stops: 17 Bunkeys Cross Stop 346211 Trip Duration: 85 min R503, Ireland Line Summary: Bilboa Cross Stop 346231, Stop No. 346191, Cappamore Stop 335131, Drumsally Cross Jerry's Bar Stop 346181 Stop 335121, Murroe Stop 335111, Cappahana Cross Stop 335101, Newport Stop 335071, Shower Castleconnell Stop 345981 Cross Stop 335061, Bunkeys Cross Stop 346211, Castle Street, Castleconnell Jerry's Bar Stop 346181, Castleconnell Stop 345981, St Flannans Terrace Stop 346001, School Road Stop St Flannans -

School Transport 2021/22

School Transport 2021/22 School Transport Policy 2021/2022 Our priority in Limerick ETSS is to ensure a safe, positive, supportive and optimal educational environment for all. Consequently, high expectations will be communicated to and required from all members of the school community. The philosophical foundations of our Code of Positive Behaviour are care, respect, positivity and personal responsibility (Restorative Practice). This School Transport Policy works in conjunction with the Limerick ETSS Code of Positive Behaviour, Anti-Bullying Policy, Suspension and Expulsion Policies. The Code of Positive behaviour also applies while on all school outings, sporting events and trips etc. Please note that the following strict protocols are in place on the school bus as follows: ● Students are assigned a specific bus for a specific route. Under no circumstances should a student use a different school bus other than the one assigned to them. Furthermore, students must not alight the bus at an alternative bus stop unless the school has been notified by parents/carers. ● Students will be assigned a seat for the entire year and must remain in this seat at all times. The school reserves the right to amend seating arrangements where necessary. ● Face coverings are mandatory and must be worn at all times (subject to government public safety guidelines). ● Eating or drinking is strictly not permitted. ● Hand sanitiser must be used when boarding and alighting the bus (subject to government public safety guidelines). ● All students will be assigned an ID card with details of their bus and seat allocation in September. This should be made visible to the bus driver when boarding the bus. -

Information and Services for Older People Across Limerick

INFORMATION AND SERVICES FOR OLDER PEOPLE ACROSS LIMERICK 1 INFORMATION AND SERVICES FOR OLDER PEOPLE ACROSS LIMERICK CONTENTS USEFUL NUMBERS .............................................................................3 SECTION 1: BEING POSITIVE: ACTIVITIES INVOLVING OLDER PEOPLE Active Retired Group .............................................................................4 PROBUS ..............................................................................................5 Courses and Activities ........................................................................5 General Course Providers ....................................................................5 Computer Skills Courses .....................................................................6 Men’s Sheds .......................................................................................7 Women’s Groups ............................................................................... 9 Get Togethers and Craft Groups .......................................................10 Cards .................................................................................................10 Bingo .................................................................................................11 Music and Dancing ............................................................................12 Day Centres ......................................................................................13 Libraries ............................................................................................18 -

Type of Treatment Limerick City

Volume Supplied Organisation Name Scheme Code Scheme Name Supply Type Population Served (m3/day) Type Of Treatment Coagulation, clarification and Flocculation, Rapid Gravity filtration Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB1001 Abbeyfeale PWS PWS 6892 2640 followed by Chlorination Coagulation, clarification and Flocculation, Rapid Gravity filtration followed by Chlorination, UV & Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB1002 Adare PWS PWS 2498 1133 Fluoridation Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB1003 Anglesboro PWS PWS 34 2 Chlorination & UV Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB2002 Ardpatrick Kilfinnane Public Water Supply PWS 1317 818 Chlorination Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB1007 Athlacca PWS PWS 130 26 Chlorination Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB1008 Ballingarry PWS PWS 994 504 Chlorination Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB1010 Ballylanders PWS PWS 620 164 Chlorination Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB1013 Bruff PWS PWS 1460 651 Chlorination Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB1014 Bruree PWS PWS 811 291 Chlorination Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB1015 Caherconlish PWS PWS 423 552 See clareville WTP & Chlorination Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB2001 Cappamore Foileen Public Water Supply PWS 2456 949 Chlorination Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB1019 Carrigkerry PWS PWS 275 108 Chlorination & UV Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB1052 Carrigmore PWS PWS 372 89 Chlorination & UV Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB1022 Castletown/Ballyagran PWS PWS 1276 -

Derelict Sites Register - 2020

DERELICT SITES REGISTER - 2020 REF NUMBER LOCATION OF LAND DESIGNATED AREA EIRCODE 1 DS-001-91 4 Wellesley Lane, (off Henry Street), Limerick. Limerick City West 2 DS-002-91 3 Wellesley Lane, (off Henry Street), Limerick. Limerick City West 3 DS-003-91 2 Wellesley Lane, (off Henry Street), Limerick. Limerick City West 4 DS-004-91 1 Wellesley Lane, (off Henry Street), Limerick. Limerick City West 5 DS-005-91 23 Wickham Street, Limerick. Limerick City West V94 XN53 6 DS-006-91 22 Wickham Street, Limerick. Limerick City West V94 P2F6 7 DS-001-93 Knightstreet, Ballingarry, Co. Limerick. Adare/Rathkeale 8 DS-004-04 West end, Kilfinane, Co. Limerick. Kilmallock/ Cappamore 9 DS-005-04 Disused Shop & Shed, Kilfinane, Co. Limerick. Kilmallock/ Cappamore 10 DS-007-04 Main St Croom, Co. Limerick. Adare/Rathkeale 11 DS-011-04 The Square, Kilfinane, Co. Limerick. Kilmallock/ Cappamore 12 DS-001-05 Market House, Kilfinane, Co. Limerick. Kilmallock/ Cappamore 13 DS-005-05 Glengort Schoolhouse, Tournafulla Newcastlewest 14 DS-008-06 Main Street, Bruff, Co. Limerick. Kilmallock/ Cappamore 15 DS-009-06 Ballyvulhane, Bruff, Co. Limerick. Kilmallock/ Cappamore 16 DS-001-07 Corgrigg, Foynes, Co. Limerick. Adare/Rathkeale 17 DS-003-08 Cogan Street, Limerick. Limerick City West 19 DS-007-08 Ballyneety North, Templebredon, Co. Limerick. Kilmallock/ Cappamore 20 DS-003-09 Creamery Store/Londis, Herbertstown, Co. Limerick. Kilmallock/ Cappamore 21 DS-002-10 Athea Upper, Athea, Co. Limerick. Newcastlewest 22 DS-017-11 Rosbrien Road / Punches Cross, Limerick. Limerick City West 23 DS-017-12 86 Lenihan Avenue, Limerick.