Necrotizing Meningoencephalitis in Atypical Dog Breeds: a Case Series and Literature Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Illustrated Guide Prepared by the American Lhasa Apso Club Breed Standard Committee the American Lhasa Apso Club Illustrated Guide to the Standard

TheAmerican Lhasa Apso Club The Lhasa Apso Illustrated Guide Prepared by The American Lhasa Apso Club Breed Standard Committee The American Lhasa Apso Club Illustrated Guide to the Standard The Lhasa Apso standard is an attempt to define an ideal specimen and is a descriptive guide by which a Lhasa Apso should be judged. The standard is not designed for the person who has never seen a Lhasa Apso but is meant as a description for those who are familiar with the breed and dogs in general. It is important, therefore, to offer this guide as a more in-depth study of the unique qualities that set the Lhasa Apso apart from other breeds and, at the same time, emphasize the characteristics that cause the Lhasa Apso to be representative of the breed. CHARACTER - GAY AND ASSERTIVE, BUT CHARY OF STRANGERS. Originating in the lonely and isolated reaches of the Himalayan mountains, Lhasa Apsos reflect their Tibetan heritage in many characteristic ways. Relatively unchanged for hundreds of years, these sturdy little mountain dogs are fastidious by nature and are guardians, especially within their domain. When looking his best, the Lhasa Apso exhibits a regal attitude. He is seldom a pet but rather a companion, often a clown, but never a fool. Lhasa exhibiting its regal attitude Lhasa playing in the snow Historically in Tibet, his primary function was that of a guardian inside Buddhist monasteries and homes of Tibetan nobility, where his intelligence, acute hearing and natural instinct for being able to identify friend from stranger made him well-suited for this role. -

Year of the DOG Bingo Myfreebingocards.Com

Year of the DOG Bingo myfreebingocards.com Safety First! Before you print all your bingo cards, please print a test page to check they come out the right size and color. Your bingo cards start on Page 4 of this PDF. If your bingo cards have words then please check the spelling carefully. If you need to make any changes go to mfbc.us/e/ywyjac Play Once you've checked they are printing correctly, print off your bingo cards and start playing! On the next two pages you will find the "Bingo Caller's Card" - this is used to call the bingo and keep track of which words have been called. Your bingo cards start on Page 4. Virtual Bingo Please do not try to split this PDF into individual bingo cards to send out to players. We have tools on our site to send out links to individual bingo cards. For help go to myfreebingocards.com/virtual-bingo. Help If you're having trouble printing your bingo cards or using the bingo card generator then please go to https://myfreebingocards.com/faq where you will find solutions to most common problems. Share Pin these bingo cards on Pinterest, share on Facebook, or post this link: mfbc.us/s/ywyjac Edit and Create To add more words or make changes to this set of bingo cards go to mfbc.us/e/ywyjac Go to myfreebingocards.com/bingo-card-generator to create a new set of bingo cards. Legal The terms of use for these printable bingo cards can be found at myfreebingocards.com/terms. -

Breed Name # Cavalier King Charles Spaniel LITTLE GUY Bernese

breed name # Cavalier King Charles Spaniel LITTLE GUY Bernese Mountain Dog AARGAU Beagle ABBEY English Springer Spaniel ABBEY Wheaten Terrier ABBEY Golden Doodle ABBIE Bichon Frise ABBY Cocker Spaniel ABBY Golden Retriever ABBY Golden Retriever ABBY Labrador Retriever ABBY Labrador Retriever ABBY Miniature Poodle ABBY 11 Nova Scotia DuckTolling Retriever ABE Standard Poodle ABIGAIL Beagle ACE Boxer ACHILLES Gordon Setter ADDIE Miniature Schnauzer ADDIE Australian Terrier ADDY Golden Retriever ADELAIDE Portuguese Water Dog AHAB Cockapoo AIMEE Labrador Retriever AJAX Dachshund ALBERT Labrador Retriever ALBERT Havanese ALBIE Golden Retriever ALEXIS Yorkshire Terrier ALEXIS Bulldog ALFIE Collie ALFIE Golden Retriever ALFIE Labradoodle ALFIE Bichon Frise ALFRED Chihuahua ALI Cockapoo ALLEGRO Border Collie ALLIE Coonhound ALY Mix AMBER Labrador Retriever AMELIA Labrador Retriever AMOS Old English Sheepdog AMY aBreedDesc aName Labrador Retriever ANDRE Golden Retriever ANDY Mix ANDY Chihuahua ANGEL Jack Russell Terrier ANGEL Labrador Retriever ANGEL Poodle ANGELA Nova Scotia DuckTolling Retriever ANGIE Yorkshire Terrier ANGIE Labrador Retriever ANGUS Maltese ANJA American Cocker Spaniel ANNABEL Corgi ANNIE Golden Retriever ANNIE Golden Retriever ANNIE Mix ANNIE Schnoodle ANNIE Welsh Corgi ANNIE Brittany Spaniel ANNIKA Bulldog APHRODITE Pug APOLLO Australian Terrier APPLE Mixed Breed APRIL Mixed Breed APRIL Labrador Retriever ARCHER Boston Terrier ARCHIE Yorkshire Terrier ARCHIE Pug ARES Golden Retriever ARGOS Labrador Retriever ARGUS Bichon Frise ARLO Golden Doodle ASTRO German Shepherd Dog ATHENA Golden Retriever ATTICUS Yorkshire Terrier ATTY Labradoodle AUBREE Golden Doodle AUDREY Labradoodle AUGIE Bichon Frise AUGUSTUS Cockapoo AUGUSTUS Labrador Retriever AVA Labrador Retriever AVERY Labrador Retriever AVON Labrador Retriever AWIXA Corgi AXEL Dachshund AXEL Labrador Retriever AXEL German Shepherd Dog AYANA West Highland White Terrier B.J. -

Cypress Creek Kennel Club of Texas AKC Sanctioned Agility Trial

Cypress Creek Kennel Club of Texas AKC Sanctioned Agility Trial Spring, TX Permission has been granted by the American Kennel Club Judges: Debby Wheeler for holding of this event under American Kennel Club rules and regulations. James P. Crowley, Secretary. CLASS SCHEDULE Friday, October 2, 2015 Ring 1: Novice JWW - 4 Entries Open JWW - 7 Entries Novice Standard - 5 Entries Open Standard - 5 Entries Master/Excellent Standard - 71 Entries Premiere Standard - 15 Entries Master/Excellent JWW - 72 Entries Premiere JWW - 14 Entries Saturday, October 3, 2015 Ring 1: Master/Excellent JWW - 93 Entries Master/Excellent Standard - 92 Entries Master/Excellent FAST - 26 Entries Open FAST - 3 Entries Novice FAST - 1 Entries Open Standard - 3 Entries Novice Standard - 3 Entries Open JWW - 3 Entries Novice JWW - 3 Entries Sunday, October 4, 2015 Ring 1: Master/Excellent JWW - 79 Entries Master/Excellent Standard - 79 Entries Time 2 Beat - 16 Entries Open Standard - 4 Entries Novice Standard - 3 Entries Open JWW - 3 Entries Novice JWW - 5 Entries PLEASE BE ATTENTIVE TO ANNOUNCEMENTS THROUGHOUT THE EVENT FOR LAST MINUTE CHANGES. There are 129 dogs entered in this event with 193 entries on Friday, 227 entries on Saturday, and 189 entries on Sunday for a total of 609 entries. 1 12101 Minipup, Shetland Sheepdog, Howard Boyle Running Order List 12102 Betty Sue, All-American, Judy Stienecker 12103 Popo, All-American, Janet Yun 12110 Bandit, Papillon, Carole Cribbs Friday, October 2, 2015 12202 Fyfa, Shetland Sheepdog, Terese Rakow 12302 Daisy, Shetland Sheepdog, -

Dog Breeds Impounded in Fy16

DOG BREEDS IMPOUNDED IN FY16 AFFENPINSCHER 4 AFGHAN HOUND 1 AIREDALE TERR 2 AKITA 21 ALASK KLEE KAI 1 ALASK MALAMUTE 6 AM PIT BULL TER 166 AMER BULLDOG 150 AMER ESKIMO 12 AMER FOXHOUND 12 AMERICAN STAFF 52 ANATOL SHEPHERD 11 AUST CATTLE DOG 47 AUST KELPIE 1 AUST SHEPHERD 35 AUST TERRIER 4 BASENJI 12 BASSET HOUND 21 BEAGLE 107 BELG MALINOIS 21 BERNESE MTN DOG 3 BICHON FRISE 26 BLACK MOUTH CUR 23 BLACK/TAN HOUND 8 BLOODHOUND 8 BLUETICK HOUND 10 BORDER COLLIE 55 BORDER TERRIER 22 BOSTON TERRIER 30 BOXER 183 BOYKIN SPAN 1 BRITTANY 3 BRUSS GRIFFON 10 BULL TERR MIN 1 BULL TERRIER 20 BULLDOG 22 BULLMASTIFF 30 CAIRN TERRIER 55 CANAAN DOG 1 CANE CORSO 3 CATAHOULA 26 CAVALIER SPAN 2 CHESA BAY RETR 1 CHIHUAHUA LH 61 CHIHUAHUA SH 673 CHINESE CRESTED 4 CHINESE SHARPEI 38 CHOW CHOW 93 COCKER SPAN 61 COLLIE ROUGH 6 COLLIE SMOOTH 15 COTON DE TULEAR 2 DACHSHUND LH 8 DACHSHUND MIN 38 DACHSHUND STD 57 DACHSHUND WH 10 DALMATIAN 6 DANDIE DINMONT 1 DOBERMAN PINSCH 47 DOGO ARGENTINO 4 DOGUE DE BORDX 1 ENG BULLDOG 30 ENG COCKER SPAN 1 ENG FOXHOUND 5 ENG POINTER 1 ENG SPRNGR SPAN 2 FIELD SPANIEL 2 FINNISH SPITZ 3 FLAT COAT RETR 1 FOX TERR SMOOTH 10 FOX TERR WIRE 7 GERM SH POINT 11 GERM SHEPHERD 329 GLEN OF IMALL 1 GOLDEN RETR 56 GORDON SETTER 1 GR SWISS MTN 1 GREAT DANE 23 GREAT PYRENEES 6 GREYHOUND 8 HARRIER 7 HAVANESE 7 IBIZAN HOUND 2 IRISH SETTER 2 IRISH TERRIER 3 IRISH WOLFHOUND 1 ITAL GREYHOUND 9 JACK RUSS TERR 97 JAPANESE CHIN 4 JINDO 3 KEESHOND 1 LABRADOR RETR 845 LAKELAND TERR 18 LHASA APSO 61 MALTESE 81 MANCHESTER TERR 11 MASTIFF 37 MIN PINSCHER 81 NEWFOUNDLAND -

An Expert's Guide to the SHIH

An Expert’s Guide to the SHIH TZU By Juliette Cunliffe Published as an EBook 2011 © Juliette Cunliffe (Author) & © Carol Ann Johnson (Photographer) AN EXPERT’S GUIDE TO THE SHIH TZU ©Juliette Cunliffe Page 1 Sample of first 8 pages only To purchase this Ebook please visit our On-Line Store at www.dogebooks.org AN EXPERT’S GUIDE TO THE SHIH TZU ©Juliette Cunliffe Page 2 CONTENTS Introduction 3 Chapter 1 A Peep into the Shih Tzu’s History 6 Chapter 2 Meet the Modern Shih Tzu 12 Chapter 3 Finding Your Shih Tzu Puppy 18 Chapter 4 Your Puppy Comes Home 25 Chapter 5 Training 30 Chapter 6 Essential Care 36 Chapter 7 Grooming 40 Chapter 8 Studying the Breed Standard 45 Chapter 9 Showing your Shih Tzu 48 Chapter 10 Health Care 52 CREDITS All photos by Carol Ann Johnson www.carolannjohnson.com and from the Author’s archive collection AN EXPERT’S GUIDE TO THE SHIH TZU ©Juliette Cunliffe Page 3 INTRODUCTION As many readers of will perhaps know, I am already a well-established author with over 50 dog books published in hardback, many of them also with editions in different languages. There are several in German and Spanish, and one of my Shih Tzu books has even appeared in Russian, so it may come as some surprise that I have decided to publish this, my first EBook. Let me explain why… I am a Championship Show judge and often when officiating abroad people have asked if I have any of my books with me for them to buy. -

Ranked by Temperament

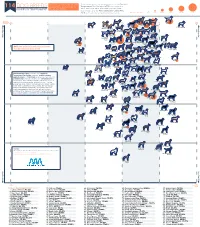

Comparing Temperament and Breed temperament was determined using the American 114 DOG BREEDS Popularity in Dog Breeds in Temperament Test Society's (ATTS) cumulative test RANKED BY TEMPERAMENT the United States result data since 1977, and breed popularity was determined using the American Kennel Club's (AKC) 2018 ranking based on total breed registrations. Number Tested <201 201-400 401-600 601-800 801-1000 >1000 American Kennel Club 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 1. Labrador 100% Popularity Passed 2. German Retriever Passed Shepherd 3. Mixed Breed 7. Beagle Dog 4. Golden Retriever More Popular 8. Poodle 11. Rottweiler 5. French Bulldog 6. Bulldog (Miniature)10. Poodle (Toy) 15. Dachshund (all varieties) 9. Poodle (Standard) 17. Siberian 16. Pembroke 13. Yorkshire 14. Boxer 18. Australian Terrier Husky Welsh Corgi Shepherd More Popular 12. German Shorthaired 21. Cavalier King Pointer Charles Spaniel 29. English 28. Brittany 20. Doberman Spaniel 22. Miniature Pinscher 19. Great Dane Springer Spaniel 24. Boston 27. Shetland Schnauzer Terrier Sheepdog NOTE: We excluded breeds that had fewer 25. Bernese 30. Pug Mountain Dog 33. English than 30 individual dogs tested. 23. Shih Tzu 38. Weimaraner 32. Cocker 35. Cane Corso Cocker Spaniel Spaniel 26. Pomeranian 31. Mastiff 36. Chihuahua 34. Vizsla 40. Basset Hound 37. Border Collie 41. Newfoundland 46. Bichon 39. Collie Frise 42. Rhodesian 44. Belgian 47. Akita Ridgeback Malinois 49. Bloodhound 48. Saint Bernard 45. Chesapeake 51. Bullmastiff Bay Retriever 43. West Highland White Terrier 50. Portuguese 54. Australian Water Dog Cattle Dog 56. Scottish 53. Papillon Terrier 52. Soft Coated 55. Dalmatian Wheaten Terrier 57. -

DOG BREEDS Affenpinscher Afghan Hound Airedale Terrier Akita

DOG BREEDS English Foxhound Polish Lowland English Setter Sheepdog Affenpinscher English Springer Pomeranian Afghan Hound Spaniel Poodle Airedale Terrier English Toy Spaniel Portuguese Water Dog Akita Field Spaniel Pug Alaskan Malamute Finnish Spitz Puli American Eskimo Dog Flat-Coated Retriever Rhodesian Ridgeback American Foxhound French Bulldog Rottweiler American Staffordshire German Pinscher Saint Bernard Terrier German Shepherd Dog Saluki American Water German Shorthaired Samoyed Spaniel Pointer Schipperke Anatolian Shepherd German Wirehaired Scottish Deerhound Dog Pointer Scottish Terrier Australian Cattle Dog Giant Schnauzer Sealyham Terrier Australian Shepherd Glen of Imaal Terrier Shetland Sheepdog Australian Terrier Golden Retriever Shiba Inu Basenji Gordon Setter Shih Tzu Basset Hound Great Dane Siberian Husky Beagle Great Pyrenees Silky Terrier Bearded Collie Greater Swiss Mountain Skye Terrier Beauceron Dog Smooth Fox Terrier Bedlington Terrier Greyhound Soft Coated Wheaten Belgian Malinois Harrier Terrier Belgian Sheepdog Havanese Spinone Italiano Belgian Tervuren Ibizan Hound Staffordshire Bull Bernese Mountain Dog Irish Setter Terrier Bichon Frise Irish Terrier Standard Schnauzer Black and Tan Irish Water Spaniel Sussex Spaniel Coonhound Irish Wolfhound Swedish Vallhund Black Russian Terrier Italian Greyhound Tibetan Mastiff Bloodhound Japanese Chin Tibetan Spaniel Border Collie Keeshond Tibetan Terrier Border Terrier Kerry Blue Terrier Toy Fox Terrier Borzoi Komondor Vizsla Boston Terrier Kuvasz Weimaraner Bouvier des -

Merseyside Toy Dog Club Open Show 30Th September 2018

MERSEYSIDE TOY DOG CLUB SCHEDULE OF 96 CLASS OPEN SHOW (Unbenched & held under Kennel Club Limited, Rules & Show Regulations) Not Judged on the Group System SPONSORED BY COBBY DOG AT CROXTETH SPORTS CENTRE ALTCROSS ROAD, LIVERPOOL L11 0BS (0ff East Lancashire Road A580/Stonebridge Lane) SUNDAY 30th SEPTEMBER 2018 B.I.S. Judge: Anthony Oakden (Spawood) Show Opens 9.30am Judging Commences 10.00am (prompt) Only undocked dogs and legally docked dogs may be entered at this show. All judges at this show agree to abide by the following statement: “In assessing dogs, judges must penalise any features or exaggeratons which they consider would be detrimental to the soundness, health and well being of the dog”. GUARANTORS TO THE KENNEL CLUB Jane Thomas (Chairman) 49 Bridge Road, Maghull, Merseyside. L31 5LX Sophie Todhunter (Secretary) 76 Hand Lane, Pennington, Leigh Yvonne Olive (Treasurer) 30 Cherry Tree Way, Bolton, BL2 3BS HON VETERINARY SURGEON; (ON CALL) Vets Now Emergency Ltd Woodfall Heath Ave Huyton, Liverpool Tel No. 0151 480 2040 ALL ENTRIES & FEES TO HON. SECRETARY: Sophie Todhunter 76 Hand Lane, Pennington, Leigh, Lancashire. WN7 3NA Tel No. 07850 450272 ENTRIES CLOSE Tuesday 28th August 2018 (POSTMARK) online entries accepted up until midnight 3rd September 2018 at www.arenaprint.co.uk All wins up to and including 21st August 2018 must be counted when entering any classes at this show SPECIAL PRIZES FOR BEST IN SHOW & BEST PUPPY IN SHOW LUCKY RING No. PRIZE DRAW 1ST £30 2ND £20 3RD £10 MERSEYSIDE TOY DOG CLUB PRESIDENT: Mrs. E.A. Houghton VICE PRESIDENT: Mrs. -

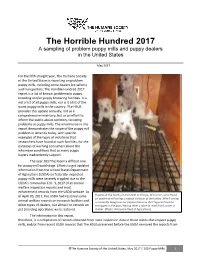

2017 Horrible Hundred Report

The Horrible Hundred 2017 A sampling of problem puppy mills and puppy dealers in the United States May 2017 For the fifth straight year, The Humane Society of the United States is reporting on problem puppy mills, including some dealers (re-sellers) and transporters. The Horrible Hundred 2017 report is a list of known, problematic puppy breeding and/or puppy brokering facilities. It is not a list of all puppy mills, nor is it a list of the worst puppy mills in the country. The HSUS provides this update annually, not as a comprehensive inventory, but as an effort to inform the public about common, recurring problems at puppy mills. The information in this report demonstrates the scope of the puppy mill problem in America today, with specific examples of the types of violations that researchers have found at such facilities, for the purposes of warning consumers about the inhumane conditions that so many puppy buyers inadvertently support. The year 2017 has been a difficult one for puppy mill watchdogs. Efforts to get updated information from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) on federally-inspected puppy mills were severely crippled due to the USDA’s removal on Feb. 3, 2017 of all animal welfare inspection reports and most enforcement records from the USDA website. As of April 20, 2017, the USDA had restored some Puppies at the facility of Alvin Nolt in Thorpe, Wisconsin, were found on unsafe wire flooring, a repeat violation at the facility. Wire flooring animal welfare records on research facilities and is especially dangerous for puppies because their legs can become other types of dealers, but almost no records on entrapped in the gaps, leaving them unable to reach food, water or pet breeding operations were restored. -

Is There a Difference Between Fawn and Black Pugs? Aside from the Color, There Is No Difference Between the Two

What is the origin of the Pug? The Pug is considered an Oriental breed with ancestral ties to the Pekingese and perhaps the Shih Tzu. There is no clear date of introduction of the Pug and many people disagree due to the lack of records available. The Pug was introduced to America just after the Civil War and was recognized by the American Kennel Club in the mid-1880’s. Is there a difference between fawn and black Pugs? Aside from the color, there is no difference between the two. On average, Pugs live about 12 years, but they’ve been known to live well beyond their average life span with proper care, nutrition and of course some good luck. Are Pugs easy to train? Pugs are moderately easy to train, making them neither easy to train, nor difficult. They maintain a stubborn streak, which can present occasional problems. Fortunately, though, a Pug is a people dog who is eager to please and receive attention. And they’re lovers of all things edible with the possible exception of lettuce and thus can be bribed to do what you want them to do rather easily. Are Pugs good apartment dogs? Absolutely! Pugs are small indoor dogs who don’t require a lot of room to run inside or outside, making them ideal for apartment dwellers. An apartment Pug needs consistent outdoor time in order to thrive in that setting. Are Pugs good with children? Yes, yes. A thousand times yes! Pugs are among the most gentle and passive breeds of all. -

The Caversham Pekingese Tony Rosato (Morningstar)

Footprints in the Breed: The Caversham Pekingese Tony Rosato (Morningstar) As we all know, many breeds have evolved considerably over time, though certainly not all. The Japanese Chin, for example, has changed very little over a period of centuries. Yet it is a close cousin to the Pekingese and both were classified as the same breed in England in 1898. It’s noteworthy to compare how the two breeds that were once so similar ended up looking so different because the Peke changed so radically. If you want to have a clearer picture, there is a beautiful Chin from 1903 preserved in the Walter Rothschild Zoological Museum in Tring i that could win in the show ring today. Japanese Spaniel of the early 1900's, Ch. Kiku of Nagoya. But you certainly couldn’t say that about “Ah Cum” (see photograph below), one of the first Pekingese champions from 1904 and an important sire, whose stuffed remains share that museum’s cabinet space with the same preserved Chin. With his protruding muzzle, long legs, short back and short dark red coat, Ah Cum would be considered someone’s nice house pet today or perhaps another breed altogether . The stuffed remains of the Pekingese founding sire of the breed, Ah Cum, in the Walter Rothschild Zoological Museum in Tring, England. Bred in the Imperial Palace in China and imported by Mrs. Douglas Murray about 1896. Ch. Goodwood Lo Improvements in Pekingese conformation came gradually of course, and you can track the progression and note which kennels were responsible for the most progress.