Kol Nidre 5775

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE MUSICAL FEATURES of 2015'S TOP-RANKED COUNTRY SONGS

THE MUSICAL FEATURES OF 2015’s TOP-RANKED COUNTRY SONGS By Mason Taylor Allen Senior Honors Thesis Department of Music University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill April 22, 2016 Approved: Dr. Jocelyn R. Neal, Thesis Advisor Dr. Allen Anderson, Reader Dr. Andrea Bohlman, Reader © 2016 Mason Taylor Allen ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Mason Taylor Allen: The Musical Features of 2015’s Top-Ranked Country Songs Under the direction of Dr. Jocelyn R. Neal The 2015 top-ten country songs analyzed in this study are characterized by the various formats of their song form, harmonies, and lyrics. This thesis presents a comprehensive study of the structure and narratives in sixty-seven songs that summarizes the distinctive features within those domains of contemporary commercial country music. A detailed description of the norm along with identifiable trends emerges. The song form that features most prominently in this repertory includes a verse-chorus-bridge form with three iterations of the chorus, an intro and outro section, and instrumental sections immediately following each chorus. The top-ten country songs have varying degrees of departure from this typical model. Primary features of the harmonies of these top songs include the frequent use of a double-tonic complex, the absence of a 5-1 authentic cadence, the same chord progression throughout the verse, chorus, and bridge, and the use of only two chords throughout the song. Lyrical analyses show that 2015 songs are continuing the traditional themes about romantic attraction, love, heartache, good times and partying, home, family, nostalgia, religion, and inspiration, within the context of small-town country life that this genre has used for years. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

It Starts with "F": a Collection of Short Stories

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 2018 It starts with "F": A collection of short stories Arielle Irvine University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2018 Arielle Irvine Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Irvine, Arielle, "It starts with "F": A collection of short stories" (2018). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 526. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/526 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright by ARIELLE IRVINE 2018 All Rights Reserved IT STARTS WITH “F”: A COLLECTION OF SHORT FICTION An Abstract of a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Arielle Irvine University of Northern Iowa May 2018 ABSTRACT It Starts with “F”: A Collection of Short Fiction consists of five short stories that share a family-centered theme while tackling tough topics such as death, separation, adoption, and personal fulfillment. IT STARTS WITH “F”: A COLLECTION OF SHORT STORIES A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Arielle Irvine University of Northern Iowa May 2018 ii This Study by: Arielle Irvine Entitled: It Starts with “F”: A Collection of Short Stories has been approved as meeting the thesis requirement for the Degree of Master of Arts ___________ __________________________________________________ Date Dr. -

Plug in Lotusland

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-13-2016 (un)plug in lotusland Laurin D. Jefferson University of New Orleans, New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Jefferson, Laurin D., "(un)plug in lotusland" (2016). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 2161. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/2161 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (un)plug in lotusland A Thesis Submitted to the graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing Poetry by Laurin DeChae Jefferson B.S. Indiana University of Pennsylvania, 2013 May, 2016 Table of Contents Preface: The Pain of Space & Proofs for Science Fiction ............................................................... 1 PROLOGUE ......................................................................................................................................... 13 i/I, you/You ........................................................................................................................................... 20 hemispheres ........................................................................................................................................... -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Julia Bryant(JB)

103 i .' BIOGRAPHICA~ SUMMARY: JULIA BRYANT, nurse Ju1 i a Bryant, ~awa:fi;an"'Po'ttugues.e, was born September 2, 1903 in Honolulu. She was raised by an aunt and her maternal grandparents in the Ka1ihi area and attended elementary schools there. Later she went to Sacred Heart's Convent in Kaimuki. She entered nurses training atQli,een'.-s Hospital ~nd graduated in 1926. After graduati on and -;t'fermarr:tage, "she: Md": private dtJ.t;Y-9ntJl~s,ffi:rig1or awhile. In 1931, she went to work in the Leprosy Hospital at Ka1ihi which was later moved to Pearl City. At times, she chaperoned. patients who were sent by plane to Kalaupapa. 1",; the early 1950's, she moved to Nanaku1i. Her hobbies are garden- ing and reading. Since her husband's death, she has taken classes and become actively involved with~a Hawaiian liHl9qa~e -group;~, 104 Tape: No.~. 2-3-1-77 ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW with Julia Bryant (JB) March 5, 1977 Waianae, Oahu, Hawaii BY: June Gutmanis (JG) JG: Did anyone wake up the family in the 'morning? JB: Usually G.randma. Only the children going school. JG:How did she wake you up? ·Did she come and shake you? .JR: Yeah, she come and ca 11 . JG; Shedidn't chant to you or sing to you, or... JB: No, no, no, no. JG: How did you go to school? JB :Walk. When I went to Kal i hiwaena Schoo1, Iwalkedite s6b0Ji>;~~,:.. , ." ....... :.... -.~ ~. JG: .What kind of lunches did you or yOur friends take to school? JB: Well, to te11 you the true fact we .hardly had butter. -

Z. Muth © 2009)

You Only Believe Me When I’m Lying (Z. Muth © 2009) I play it cool and act as cold as ice It’s the only way I know to make you look twice ‘cause you only believe me when I’m lying I slam the door but I watch what I say I know it’s just your jealous heart that’s making you stay Where you only believe me when I’m lying And I’m not gonna send you no love letters ‘cause you’ll just shake your head at the proof that I want you and that’s the honest truth I’ve been talking to this fella next door Been giving him the eye, but he’s asking for more ‘cause you only believe me when I’m lying It’s hard to say exactly when I knew That I was on the outside looking in at you You only believe me when I’m lying And I’m not gonna send you no love letters Cause you’ll just shake your head at the proof That I want you and that’s the honest truth Hey Little Darlin’ (Z. Muth © 2009) Chorus: Hey little darlin’ I’ve been callin’ but you don’t seem to hear I’ve been waitin’ I’ve been hesitatin’ but I have waited my share I’ve been hot and I’ve been cold, been carrying a heavy load Trying to lift myself above this old life If I’m here or if I’m there, I can tell that you don’t care ‘Cause you’ve got a heart like a bucket full of ice Chorus: Well the old folks back home, they wonder why I roam And chase the crooked and cold hearted men like you They tried to teach me well but you have cast some kind of spell And I am bound to fall until my days are through And I tell myself no, but you know in the end I’ll always go Back down to the bar to look for you Then I’m right back where I started, all alone and broken hearted Hey, what’s a girl like me supposed to do? Then you ask me how I’ve been I said I came out on top but you could hardly call it winnin’ With that hard look in your eyes Well I know now it ain’t no disguise Ain’t no disguise Chorus: I Used to Call My Heart a Home (Z. -

2013 Update by Artist

2013 UPDATE BY ARTIST ARTIST TITLE DISC # Aldean, Jason 1994 ASK1303B 1 Aldean, Jason 1994 SSC423 1 Aldean, Jason I Don't Do Lonely Well SSC422 2 Aldean, Jason Night Train SSC427 7 Aldean, Jason Night Train ASK2013-1 12 Aldean, Jason & Luke Bryan & Eric Church The Only Way I Know SSC421 7 Allan, Gary Every Storm (Runs Out Of Rain) SSC421 3 Allan, Gary Pieces SSC424 6 Allen, Lily Hard Out Here ZM2013-3 17 Allen, Lily Somewhere Only We Know ZM2013-3 18 Aplin, Gabrielle Please Don't Say You Love Me ZM2013-2 8 Arthur, James Your Nobody Til Somebody Loves You ZM2013-2 12 Avicii Hey Brother ZM2013-1 2 Avicii I Could Be The One ZM2013-1 5 Avicii Wake Me Up ZM2013-1 4 Avicii You Make Me ZM2013-1 3 Band Perry Better Dig Two SSC421 1 Band Perry, The Chainsaw SSC426 2 Band Perry, The Done ASK1303A 5 Barlow, Gary Let Me Go ZM2013-2 10 Bastille Of The Night ZM2013-1 6 Bastille Pompeli ZM2013-1 7 Bentley, Dierks Tip It On Back SSC421 8 Bieber, Justin Heartbreaker ZM2013-3 6 Blunt, James Bonfire Heart ZM2013-2 13 Boyzone Love Will Save The Day ZM2013-1 8 Bradbery, Danielle Heart of Dixie, The SSC426 8 Brice, Lee I Drive Your Truck ASK1301A 3 Brice, Lee I Drive Your Truck SSC422 3 Brice, Lee Parking Lot Party ASK2013-2 4 Brice, Lee Parking Lot Party SSC426 5 Brown, Miss Willie You're All That Matters To Me ASK1301A 9 Bryan, Luke Been There Done That SSC420 1 Bryan, Luke Buzzkill ASK1303A 3 Bryan, Luke Buzzkill SSC423 3 Bryan, Luke Crash My Party ASK2013-1 2 Bryan, Luke Crash My Party SSC424 2 Bryan, Luke Drink A Beer SSC429 1 Bryan, Luke That's My Kind -

Songs by Artist

YouStarKaraoke.com Songs by Artist 602-752-0274 Title Title Title 1 Giant Leap 1975 3 Doors Down My Culture City Let Me Be Myself (Wvocal) 10 Years 1985 Let Me Go Beautiful Bowling For Soup Live For Today Through The Iris 1999 Man United Squad Loser Through The Iris (Wvocal) Lift It High (All About Belief) Road I'm On Wasteland 2 Live Crew The Road I'm On 10,000 MANIACS Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I M Gone Candy Everybody Wants Doo Wah Diddy When I'm Gone Like The Weather Me So Horny When You're Young More Than This We Want Some PUSSY When You're Young (Wvocal) These Are The Days 2 Pac 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Trouble Me California Love Landing In London 100 Proof Aged In Soul Changes 3 Doors Down Wvocal Somebody's Been Sleeping Dear Mama Every Time You Go (Wvocal) 100 Years How Do You Want It When You're Young (Wvocal) Five For Fighting Thugz Mansion 3 Doors Down 10000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Road I'm On Because The Night 2 Pac & Eminem Road I'm On, The 101 Dalmations One Day At A Time 3 LW Cruella De Vil 2 Pac & Eric Will No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) 10CC Do For Love 3 Of A Kind Donna 2 Unlimited Baby Cakes Dreadlock Holiday No Limits 3 Of Hearts I'm Mandy 20 Fingers Arizona Rain I'm Not In Love Short Dick Man Christmas Shoes Rubber Bullets 21St Century Girls Love Is Enough Things We Do For Love, The 21St Century Girls 3 Oh! 3 Wall Street Shuffle 2Pac Don't Trust Me We Do For Love California Love (Original 3 Sl 10CCC Version) Take It Easy I'm Not In Love 3 Colours Red 3 Three Doors Down 112 Beautiful Day Here Without You Come See Me -

David Lee Murphy Bio with Picture 2018

Million-selling singer-songwriter David Lee Murphy had no plans to make a new record until a country superstar made them for him. “I’ve been friends and written songs with Kenny (Chesney) for years,” Murphy reflects. “I sent him some songs for one of his albums a couple of years ago, and he called me up. He goes, ‘Man, you need to be making a record. I could produce it with Buddy Cannon, and I think people would love it.’ It’s hard to say no to Kenny Chesney when he comes up with an idea like that.” Murphy, whose songs “Dust on the Bottle and “Party Crowd” continue to be staples at country radio, could have easily filled the album with hits he’s written for Chesney (“’Til It’s Gone,” “Living in Fast Forward,” “Live a Little”), Jason Aldean (“Big Green Tractor,” “The Only Way I Know How”), Thompson Square (GRAMMY-nominated “Are You Gonna Kiss Me Or Not”), Jake Owen (“Anywhere With You”), or Blake Shelton (“The More I Drink”). But, Chesney had other ideas. “Kenny was really influential in the songs that we picked,” says Murphy. “Over the course of the next year or so, we got together, talked about it and picked out songs. I wanted to record songs of mine that people haven’t heard before, that are new. We wanted to make the kind of album that you would listen to if you were camping or out on a lake, fishing. Or sitting anywhere, just having a good time.” Titled No Zip Code, the new David Lee Murphy collection has already yielded a hit single and duet with Chesney, “Everything’s Gonna Be Alright.” The collection also contains such good-time, party-hearty anthems as “Get Go,” “Haywire” and “That’s Alright.” The rocking “Way Gone” is a female-empowerment barn burner. -

Diary of a Boozer Off the Booze

diary of a boozer (off the booze) By Jeff Hughes General Note on the Diary. Each diary entry will be written on the date specified. It will be edited for grammar at the end of this eight-week dry run but the thoughts will not be altered in any way. How I feel at the moment of writing is how I feel. January 23, 2017 I drink. But what I’ve done over the last decade plus is more than just drinking. I’ve made bars a central preoccupation of my life. Hard day’s work? Edge offers at 5 o’clock. Traveling to Spiddal, Ireland…Dinan, France…Groveland, California? Pints in the oldest bar a must and texts to my uncle will follow. (Can’t go wrong with Tigh Hughes, Saint-Saveur and Iron Door respectively.) Theatre tickets? Drinks before. If it’s good or really bad, way more drinks after. Bears game on? Josie Woods for endless Coors Lights. Most of the great stories of my life have occurred with a drink in my hand. Since 2003 there have probably been three weeks where I didn’t have a single drink. Two of which involved devil viruses that left me sweating through tee-shirts on a dirty couch, coming to-and-fro consciousness during random episodes of the Twilight Zone. The other just wrapped. It is the first of eight intended weeks without a drop of alcohol. Why? Because I’m hitting the reset button on my drinking life. I never wanted booze to become routine. I never wanted to lose the enjoyment of that first sip of Guinness. -

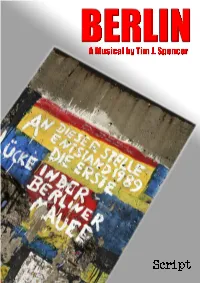

BERLIN by Tim J

1 BERLIN By Tim J. Spencer List of main characters Gustav Muller – ages between 26 & 49 Elin Muller – 24 & 47, Gustav’s wife Beppo Fischer – 26 – Gustav’s best friend Lutz Templin – 28 & 51 – another friend / IM Hans Fischer – 36 & 59 Jailer at Bautzen Prison Marietta Fischer – 33 & 56 His wife Paul Freidrich – 45 & 68 Deputy of Arbeitsgruppe 6 Joshua Fischer/Muller – son of Elin - 23 List of sub characters Rando Stiller – West Berliner – 40-63 Olga Stiller – Rando’s wife – 38-61 Cabaret Singer – ageless + A Chorus Place The city of Berlin, Germany The action takes place in two times The First Act during the period March 18th – October 18th 1966 The Second during the period October 18th – November 9th 1989 culminating in the climax on the night the Berlin Wall was freed. The Green Panda Music Company www.greenpandatheatre.co.uk – [email protected] 2 BERLIN Act One 1966 PROLOGUE Music 1 Overture [PROJECTION ON SCREEN] [We see a rebuilding of Berlin after the Second World War and then we see the building of the Berlin Wall from 1961] [SEVERAL CAST ENTER AND CREATE TABLEAU of Elin and Gustav’s wedding where Gustav is flanked by Beppo, also at the scene is Lutz – these must be defined characters visible to the audience as the later players in the show. The Wall theme breaks in and we see the Berlin Wall for the first time,, Beppo now becomes the central character as we move into first scene on the streets of Berlin in front of the Wall, Lutz also must be still on stage as he is in the first scene, the rest of the cast exit] ACT ONE – SCENE ONE Berlin Street and Wall [Beppo is now lit in a follow spotlight as he sings the opening part of this number.