Job Hazard Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tag out a Shipyard Hazard Prevention Course

Workshop Objectives At the completion of this workshop it is expected that all trainees will pass a quiz, have the ability to identify energy hazards and follow both OSHA and NAVSEA safety procedures associated with: Electrical Hazards Non-Electrical Energy Hazards Lockout - Tag out 11 OSHA 1915.89 SUBPART F Control of Hazardous Energy -Lock-out/ Tags Plus This CFR allows specific exemptions for shipboard tag-outs when Navy Ship’s Force personnel serve as the lockout/tags-plus coordinator and maintain control of the machinery per the Navy’s Tag Out User Manual (TUM). Note to paragraph (c)(4) of this section: When the Navy ship's force maintains control of the machinery, equipment, or systems on a vessel and has implemented such additional measures it determines are necessary, the provisions of paragraph (c)(4)(ii) of this section shall not apply, provided that the employer complies with the verification procedures in paragraph (g) of this section. Note to paragraph (c)(7) of this section: When the Navy ship's force serves as the lockout/tags-plus coordinator and maintains control of the lockout/tags-plus log, the employer will be in compliance with the requirements in paragraph (c)(7) of this section when coordination between the ship's force and the employer occurs to ensure that applicable lockout/tags-plus procedures are followed and documented. 2 Note to paragraph (e) of this section: When the Navy ship's force shuts down any machinery, equipment, or system, and relieves, disconnects, restrains, or otherwise renders safe all potentially hazardous energy that is connected to the machinery, equipment, or system, the employer will be in compliance with the requirements in paragraph (e) of this section when the employer's authorized employee verifies that the machinery, equipment, or system being serviced has been properly shut down, isolated, and deenergized. -

1. Identification

SAFETY DATA SHEET Issuing Date: 13-Aug-2020 Revision date 13-Aug-2020 Revision Number 1 1. IDENTIFICATION Product Name Tide PODS Spring Meadow Product Identifier 91943772_RET_NG Product Type: Finished Product - Retail Recommended use Detergent. Restrictions on use Use only as directed on label. Synonyms C-91943772-005 Details of the supplier of the safety PROCTER & GAMBLE - Fabric and Home Care Division data sheet Ivorydale Technical Centre 5289 Spring Grove Avenue Cincinnati, Ohio 45217-1087 USA Procter & Gamble Inc. P.O. Box 355, Station A Toronto, ON M5W 1C5 1-800-331-3774 E-mail Address [email protected] Emergency Telephone Transportation (24 HR) CHEMTREC - 1-800-424-9300 (U.S./ Canada) or 1-703-527-3887 Mexico toll free in country: 800-681-9531 2. HAZARD IDENTIFICATION "Consumer Products", as defined by the US Consumer Product Safety Act and which are used as intended (typical consumer duration and frequency), are exempt from the OSHA Hazard Communication Standard (29 CFR 1910.1200). This SDS is being provided as a courtesy to help assist in the safe handling and proper use of the product. This product is classified under 29CFR 1910.1200(d) and the Canadian Hazardous Products Regulation as follows:. Hazard Category Acute toxicity - Oral Category 4 Eye Damage / Irritation Category 2B Signal word Warning Hazard statements Harmful if swallowed Causes eye irritation Hazard pictograms 91943772_RET_NG - Tide PODS Spring Meadow Revision date 13-Aug-2020 Precautionary Statements Keep container tightly closed Keep away from heat/sparks/open flames/hot surfaces. — No smoking Wash hands thoroughly after handling Precautionary Statements - In case of fire: Use water, CO2, dry chemical, or foam for extinction Response IF IN EYES: Rinse cautiously with water for several minutes. -

Acute Incidents During Anaesthesia a Small Percentage of Apparently Routine Anaesthetics Will End in an Anticipated Or Unforeseen Acute Incident

Acute incidents during anaesthesia A small percentage of apparently routine anaesthetics will end in an anticipated or unforeseen acute incident. Edwin W Turton, MB ChB, Dip Pec (SA), DA (SA), MMed Anes, FCA (SA) Head of Cardiothoracic Anaesthesia, Bloemfontein Hospitals Complex, Department of Anaesthesiology, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein Dr Edwin Turton worked as a clinical fellow in cardiac anaesthesia at Glenfield Hospital, Leicester, UK, in 2009. His current fields of interest are adult and paediatric cardiac anaesthesia and peri-operative echocardiography, and focussed assessment through echocardiography in emergency care. Correspondence to: E W Turton ([email protected]) Anaesthesia is uneventful in the majority Although anaesthesia is a very well- • Antibiotics (2.6%) of cases but in a small percentage of controlled and governed discipline, acute • Benzodiazepines (2%) routine and emergency cases there will incidents do occur. Incidents can occur • Opioids (1.7%) be an anticipated or an unforeseen acute during induction, maintenance and • Other agents (e.g. radio contrast media) incident. These incidents need immediate emergence from anaesthesia. (2.5%). theoretical knowledge and clinical skills to be managed effectively and to The following acute critical incidents are Treatment and management prevent further morbidity and mortality. discussed in this article: • Stop administration of all suspected Therefore all providers of anaesthesia, • Anaphylaxis agents. at different levels of experience, should • Aspiration • Call for help. be able to provide basic and advanced • Laryngospasm • Airway must be secured and 100% cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).1 • High or total (complete) spinal blocks in oxygen given, and ensure adequate obstetric anaesthesia. ventilation. The first death associated with an anaesthetic • Intravenous or intramuscular adrenaline was reported in 1848 in the USA. -

A Model for Mandatory Job Safety Analysis Embedded in the Premit-To-Work System >

International Gas Union Research Conference 2011 <A MODEL FOR MANDATORY JOB SAFETY ANALYSIS EMBEDDED IN THE PREMIT-TO-WORK SYSTEM > Main author I. K. Yoon KOREA ABSTRACT Permit to Work (PTW) systems is defined as "a formal documented system used to control the certain types of work that are potentially hazardous". Generally, PTW system should be designed to specify the work to be done safely and the precaution to be taken as well as approval, responsibility, permissions of work. For this reason, PTW is regarded as one of the most important safety management system to control the risk of maintenance that causes 30% of the accident in chemical industries. In the early days, PTW was based on paper based system. But recently has continued to evolve into a computer based system. And these advanced systems has been applied to 80% of oil industry in North Sea and upgraded with providing the hazard information as well as supporting documentation. Usually, the hazard information is provided in the form of hazard checklist or attached risk assessment report such as JSA sheet. But when we consider the various types of work, place and environment, all the potential work related hazard cannot be reviewed in the form of prescribed checklist or certain attachment. To review the potential hazard perfectly, the work permit should be supported by Job Safety Analysis (JSA). But it has rarely been seen that company have a rule to require the mandatory JSA whenever permit to work is accomplished. Despite a relatively simple analysis structure, it is time-consuming and person-consuming methodology to complete all the procedure. -

Personal Protective Equipment Hazard Assessment

WORKER HEALTH AND SAFETY Personal Protective Equipment Hazard Assessment Oregon OSHA Personal Protective Equipment Hazard Assessment About this guide “Personal Protective Equipment Hazard Assessment” is an Oregon OSHA Standards and Technical Resources Section publication. Piracy notice Reprinting, excerpting, or plagiarizing this publication is fine with us as long as it’s not for profit! Please inform Oregon OSHA of your intention as a courtesy. Table of contents What is a PPE hazard assessment ............................................... 2 Why should you do a PPE hazard assessment? .................................. 2 What are Oregon OSHA’s requirements for PPE hazard assessments? ........... 3 Oregon OSHA’s hazard assessment rules ....................................... 3 When is PPE necessary? ........................................................ 4 What types of PPE may be necessary? .......................................... 5 Table 1: Types of PPE ........................................................... 5 How to do a PPE hazard assessment ............................................ 8 Do a baseline survey to identify workplace hazards. 8 Evaluate your employees’ exposures to each hazard identified in the baseline survey ...............................................9 Document your hazard assessment ...................................................10 Do regular workplace inspections ....................................................11 What is a PPE hazard assessment A personal protective equipment (PPE) hazard assessment -

Permits-To-Work in the Process Industries

SYMPOSIUM SERIES NO. 151 # 2006 IChemE PERMITS-TO-WORK IN THE PROCESS INDUSTRIES John Gould Environmental Resources Management, Suite 8.01, 8 Exchange Quay, Manchester M5 3EJ; [email protected] The paper presents the collective results from a number of Safety Management System audits. The audit protocol is based on the Health and Safety Executive pub- lication ‘Successful health and safety management’ and takes into account formal (written) and informal procedures as well as their implementation. Focused on permit-to-work systems, these have shown a number of common failings. The most common failure in implementing a permit-to-work system is the issue of too many permits. However, the audit protocol considers the whole risk control system. The failure to ‘close’ the management loop with an effective regular review process is the largest obstacle to an effective permit system. INTRODUCTION ‘Permits save lives – give them proper attention’. This is a startling statement made by the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) in its free leaflet IND(G) 98 (Rev 3) PTW systems. The leaflet goes on to state that two thirds of all accidents in the chemical industry are main- tenance related, with the permit-to-work (PTW) failures being the largest single cause. Given these facts, it comes as no surprise that PTW systems are a key part in the provision of a safe working environment. Over the past four years Environmental Resources Management (ERM) has been auditing PTW systems as part of its key risk control systems audits. Numerous systems have been evaluated from a wide rage of industries, covering personal care products man- ufacturing to refinery operations. -

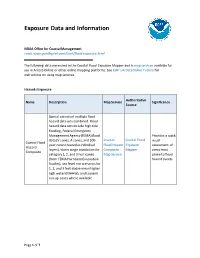

Data and Information

Exposure Data and Information NOAA Office for Coastal Management coast.noaa.gov/digitalcoast/tools/flood-exposure.html The following data were used in the Coastal Flood Exposure Mapper and in map services available for use in ArcGIS Online or other online mapping platforms. See ESRI’s ArcGIS Online Tutorial for instructions on using map services. Hazards Exposure Authoritative Name Description Map Service Significance Source Spatial extents of multiple flood hazard data sets combined. Flood hazard data sets include high tide flooding, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) flood Provides a quick data (V zones, A zones, and 500- Coastal Coastal Flood visual Coastal Flood year zones treated as individual Flood Hazard Exposure assessment of Hazard layers), storm surge inundation for Composite Mapper areas most Composite category 1, 2, and 3 hurricanes Map Service prone to flood (from FEMA Hurricane Evacuation hazard events. Studies), sea level rise scenarios for 1, 2, and 3 feet above mean higher high water (MHHW), and tsunami run-up zones where available. Page 1 of 7 Authoritative Name Description Map Service Significance Source Areas that flood when coastal flood warning thresholds are exceeded. Derived from the flood frequency layer within the Sea Level Rise and Coastal Flooding Impacts Viewer. High Tide Sea Level Rise Areas subject to High Tide Flooding Viewer high tide Flooding For islands in the Caribbean and Map Service flooding. Pacific, the high tide flooding zones were mapped based on statistical analysis of water level observations at tidal stations in those areas. Digital FEMA flood data. The data represent the digital riverine and coastal flood zones available as of FEMA Flood FEMA’s Map FEMA Flood Areas at risk October 2017 and are a Zones Map Service Center Zones from flooding. -

Conducting a Job Safety Analysis to Eliminate Hazards

Practical Tips CONDUCTING A JOB SAFETY ANALYSIS TO ELIMINATE HAZARDS What is Job Safety Analysis? A job safety analysis (JSA) is a method for making your job safer. In a JSA, you do three things: 1. Observe step-by-step how a worker does an on-the-job task. 2. Look for possible hazards in each step of the task. 3. Suggest ways to eliminate or reduce each hazard so each step of the task is safer. A supervisor and typically two to three employees who know many steps involved in a job usually make up a JSA team. This number can vary depending on the complexity of the equipment or process. One employee can actually do the steps of the task. The others watch and write down on a JSA worksheet what they see. Performing the Job Safety Analysis Listing the Steps in the Task While one employee performs the task, the others watch and write down each step of the task. Keep the following tips in mind as you make the list in the first column of the JSA form: • List from 8 to 10 task steps that you can see. • Number each step. • List the steps in the order in which they are performed. • Use actions words such as "turn on," "load," "steer," or "unload." • Ask yourself, "What step starts this task?" List the first step, such as "put on PPE." • Then ask yourself, "What is the next basic step?" • List the next steps, such as "check that power is OFF" or "get into the operator's seat." • Tell completely but briefly what is done in each step, such as "lift the load and back out." Do not tell how the step is done, "lift the load with the fork slightly raised and back out slowly." • Continue in this way until you have listed every basic step in the task. -

Hazards Analysis Report

PROJECT MANAGEMENT Doc. No. LUSI SUB-SYSTEM DOCUMENT PM-391-001-34 R0 1.1 Management Hazards Analysis Report Technical Contact: Nadine Kurita LUSI Chief Engineer Signature Date Approved by: Tom Fornek LUSI Project Manager Signature Date Approved by: John Galayda LCLS Project Director Signature Date Rev Description Date 0 Initial Release July 8, 2008 PM-391-001-34 R0 Verify that this is the latest revision. 1 of 34 Check for change orders or requests TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction............................................................................................................. 3 1.1 Purpose and Scope .............................................................................................. 3 1.2 Environment, Worker and Public Safety ............................................................ 3 2. Summary................................................................................................................. 4 2.1 Overview of Hazards .......................................................................................... 4 2.2 Comprehensiveness of the Safety Analysis ........................................................ 5 2.3 Appropriateness of the Accelerator Safety Envelope ......................................... 5 3. Project Description..................................................................................................5 3.1 X-Ray Pump/Probe Diffraction Instrument........................................................ 6 3.2 Coherent X-ray Imaging Instrument.................................................................. -

Personal Protective Equipment/Job Hazard Analysis Program

SALISBURY UNIVERSITY PPE/JOB HAZARD ANALYSIS STANDARD PRACTICE INSTRUCTION DATE: January 15, 2019 SUBJECT: Personal Protective Equipment/Job Hazard Analysis Program REGULATORY STANDARD: 29 CFR §1910.132-138. I. PURPOSE: The purpose of this program is to establish procedures for wearing Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) by all Salisbury University employees, contractors and visitors on campus. This program supports compliance with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) standards that cover PPE, specifically, 29 CFR 1910.132, .133, .135, .136 and .138. This program applies to all University employees, contractors and visitors who work in areas that contain hazards to the eyes, face, head, hands and feet. Respiratory and noise hazards are covered in the S0U Respiratory Protection Program and the SU Hearing Conservation Program. II. DEFINITIONS: ANSI (American National Standards Institute): A nonprofit organization that approves national safety standards. Ophthalmologist: A physician/surgeon who specializes in diagnosing and treating eye diseases and disorders. Optician: A skilled technician who, when given a medical prescription, is qualified to make, fit and dispense eyeglasses and contact lenses, either in an optical laboratory or for retail sale to the public; opticians do not examine patients or write prescriptions. Optometrist: A licensed primary eye-care provider who performs eye examinations, prescribes and dispenses eyeglasses and contact lenses and performs some diagnostic work, such as screening for glaucoma or cataracts. Plano: A common term for nonprescription safety glasses. PPE: Personal Protective Equipment III. RESPONSIBILITIES: A. The Program Administrator The SU PPE Program Administrator is the Director of Sustainability & Environmental Safety. Responsibilities include: Modify only under the supervision of the Safety Manager. -

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Guide

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Guide Volume 1: General PPE February 2003 F417-207-000 This guide is designed to be used by supervisors, lead workers, managers, employers, and anyone responsible for the safety and health of employees. Employees are also encouraged to use information in this guide to analyze their own jobs, be aware of work place hazards, and take active responsibility for their own safety. Photos and graphic illustrations contained within this document were provided courtesy of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), Oregon OSHA, United States Coast Guard, EnviroWin Safety, Microsoft Clip Gallery (Online), and the Washington State Department of Labor and Industries. TABLE OF CONTENTS (If viewing this pdf document on the computer, you can place the cursor over the section headings below until a hand appears and then click. You can also use the Adobe Acrobat Navigation Pane to jump directly to the sections.) How To Use This Guide.......................................................................................... 4 A. Introduction.........................................................................................6 B. What you are required to do ..............................................................8 1. Do a Hazard Assessment for PPE and document it ........................................... 8 2. Select and provide appropriate PPE to your employees................................... 10 3. Provide training to your employees and document it ........................................ 11 -

The Bullying of Teachers Is Slowly Entering the National Spotlight. How Will Your School Respond?

UNDER ATTACK The bullying of teachers is slowly entering the national spotlight. How will your school respond? BY ADRIENNE VAN DER VALK ON NOVEMBER !, "#!$, Teaching Tolerance (TT) posted a blog by an anonymous contributor titled “Teachers Can Be Bullied Too.” The author describes being screamed at by her department head in front of colleagues and kids and having her employment repeatedly threatened. She also tells of the depres- sion and anxiety that plagued her fol- lowing each incident. To be honest, we debated posting it. “Was this really a TT issue?” we asked ourselves. Would our readers care about the misfortune of one teacher? How common was this experience anyway? The answer became apparent the next day when the comments section exploded. A popular TT blog might elicit a dozen or so total comments; readers of this blog left dozens upon dozens of long, personal comments every day—and they contin- ued to do so. “It happened to me,” “It’s !"!TEACHING TOLERANCE ILLUSTRATION BY BYRON EGGENSCHWILER happening to me,” “It’s happening in my for the Prevention of Teacher Abuse repeatedly videotaping the target’s class department. I don’t know how to stop it.” (NAPTA). Based on over a decade of without explanation and suspending the This outpouring was a surprise, but it work supporting bullied teachers, she target for insubordination if she attempts shouldn’t have been. A quick Web search asserts that the motives behind teacher to report the situation. revealed that educators report being abuse fall into two camps. Another strong theme among work- bullied at higher rates than profession- “[Some people] are doing it because place bullying experts is the acute need als in almost any other field.