Open Aparna Parikh Thesis.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRAMPED for ROOM Mumbai’S Land Woes

CRAMPED FOR ROOM Mumbai’s land woes A PICTURE OF CONGESTION I n T h i s I s s u e The Brabourne Stadium, and in the background the Ambassador About a City Hotel, seen from atop the Hilton 2 Towers at Nariman Point. The story of Mumbai, its journey from seven sparsely inhabited islands to a thriving urban metropolis home to 14 million people, traced over a thousand years. Land Reclamation – Modes & Methods 12 A description of the various reclamation techniques COVER PAGE currently in use. Land Mafia In the absence of open maidans 16 in which to play, gully cricket Why land in Mumbai is more expensive than anywhere SUMAN SAURABH seems to have become Mumbai’s in the world. favourite sport. The Way Out 20 Where Mumbai is headed, a pointer to the future. PHOTOGRAPHS BY ARTICLES AND DESIGN BY AKSHAY VIJ THE GATEWAY OF INDIA, AND IN THE BACKGROUND BOMBAY PORT. About a City THE STORY OF MUMBAI Seven islands. Septuplets - seven unborn babies, waddling in a womb. A womb that we know more ordinarily as the Arabian Sea. Tied by a thin vestige of earth and rock – an umbilical cord of sorts – to the motherland. A kind mother. A cruel mother. A mother that has indulged as much as it has denied. A mother that has typically left the identity of the father in doubt. Like a whore. To speak of fathers who have fought for the right to sire: with each new pretender has come a new name. The babies have juggled many monikers, reflected in the schizophrenia the city seems to suffer from. -

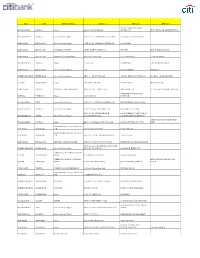

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

Frankenstein's Avatars: Posthuman Monstrosity in Enthiran/Robot

Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities (ISSN 0975-2935), Vol. 10, No. 2, 2018 [Indexed by Web of Science, Scopus & approved by UGC] DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v10n2.23 Full Text: http://rupkatha.com/V10/n2/v10n223.pdf Frankenstein’s Avatars: Posthuman Monstrosity in Enthiran/Robot Abhishek V. Lakkad Doctoral Research Candidate, Centre for Studies in Science, Technology and Innovation Policy (CSSTIP), School of Social Sciences, Central University of Gujarat, Gujarat. ORCID ID: 0000-0002-0330-0661. Email: [email protected] Received January 31, 2018; Revised April 22, 2018; Accepted May 19, 2018; Published May 26, 2018. Abstract This paper engages with ‘Frankenstein’ as a narrative structure in Indian popular cinema, in the context of posthumanism. Scholarship pertaining to monsters/monstrosity in Indian films has generally been addressed within the horror genre. However, the present paper aspires to understand monstrosity/monsters as a repercussion of science and technology (S&T) through the cinematic depiction of Frankenstein-like characters, thus shifting the locus of examining monstrosity from the usual confines of horror to the domain of science fiction. The paper contends Enthiran/Robot (Shankar 2010 Tamil/Hindi) as an emblematic instance of posthuman monstrosity that employs a Frankenstein narrative. The paper hopes to bring out the significance of cinematic imagination concerning posthuman monstrosity, to engage with collective social fears and anxieties about various cutting-edge technologies as well as other socio-cultural concerns and desires at the interface of S&T, embodiment and the society/nation. Keywords: Posthumanism, Monstrosity, Frankenstein, Indian popular cinema, Science Fiction, Enthiran/Robot The Frankenstein narrative and Posthuman Monstrosity It has been argued that in contemporary techno-culture Science Fiction (hereafter SF) performs the role of “modern myth(s)” (Klein, 2010, p.137). -

The Vulnerability of Global Cities to Climate Hazards

The Vulnerability of Global Cities to Climate Hazards Andrew Schiller*, Alex de SherbininU, Wen-Hua Hsieh*, Alex PulsipherUU * George Perkins Marsh Institute, Clark University U Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN), Columbia University UU Graduate School of Geography, Clark University Abstract Vulnerability is the degree to which a system or unit is likely to expierence harm due to exposure to perturbations or stress. The vulnerability concept emerged from the recognition that a focus on perturbations alone was insufficient for understanding responses of and impacts on the peoples, ecosystems, and places exposed to such perturbations. With vulnerability, it became clear that the ability of a system to attenuate stresses or cope with consequences constituted an important determinant of system response, and ultimately, of system impact. While vulnerability can expand our ability to understand how harm to people and ecosystems emerges and how it can be reduced, to date vulnerability itself has been conceptually hampered. It tends to address single stresses or perturbations on a system, pays inadequate attention to the full range of conditions that may render the system sensitive to perturbations or permit it to cope, accords short shrift to how exposed systems themselves may act to amplify, attenuate, or even create stresses, and does not emphasize the importance of human-environment interactions when defining the system exposed to stresses. An extended framework for vulnerability designed to meet these needs is emerging from a joint research team at Clark University, the Stockholm Environment Institute, Harvard University, and Stanford University, of which several authors on this paper are part. -

Ahmedabad Maninagar Shop No

Ahmedabad Maninagar Shop No - 1/A, 1St Floor, Rudraksh, Nr. Fire Station, Krishnabaug, Kanakaria-Maninagar Road, Pin Code - 380008 Prahlad Nagar- Corporate Road Shop No.2, Ashirwad Paras, Corporate Road, Prahlad Nagar, Pin Code - 380015 Satellite Rd- Gulmohar Mall Shop No.05, Ground Floor, Gulmohar Park Mall, Satellite Road, Pin Code - 380015 Shyamal Cross Rd Shop No G-13, Shangrila Arcade, Nr. Shayamal Cross Road, Satellite, Pin Code - 380015 University Road- Next to CCD Acumen, Ground Floor, University Road, Next To CCD, Pin Code - 380015 Vastrapur- Alpha 1 Mall Hypercity, Alpha One Mall, Vastrapur, Pin Code - 380054 Vastrapur- Himalaya Mall Shop No. 105, Ground Floor, Himalaya Mall, Memnagar, Pin Code - 380059 Bengaluru Bengaluru - Indiranagar Ground Floor, Next To CCD, MSK Plaza, Defense Colony, 100 Ft Road, Indiranagar, HAL 2Nd Stage Pin Code - 560038 Bengaluru - Jaya Nagar Ground Floor, Rajlaxmi Arcade, 9Th Main, 3Rd Block Pin Code - 560011 Blore - Hypercity Meenakshi Mall Inside Hypercity, Royal Meenakshi Mall, Bannerghatta Main Road, Pin Code - 560076 Brooke Field- Hypercity Ground Floor, Hypercity, Embassy Paragon, Kundalahalli Gate, ITPL Road, Whitefield Pin Code - 560037 Mumbai Andheri E- Tandon Mall Shop No. 4, Ground Floor, Tandon Mall, 127, Andheri Kurla Road, Andheri (E), Pin Code - 400049 Andheri W- Four Bungalows Shop No. 1 & 2, Building No. 24, Ashish CHS Ltd, St. Louis Road, Andheri (W), Pin Code - 400053 Andheri W- Lokhandwala 4,5,6 & 7, Silver Springs, Opp. HDFC Bank, Lokhandwala, Andheri (W) Pin Code - 400053 Andheri W- Shoppers Stop Level 4B, Shopper Stop, S.V. Road, Andheri (W) Pin Code - 400058 Bandra - Turner Road Hotel Grand Residency, Junction Of 24Th & 29Th Road, Off Turner Road, Near Tavaa Restaurant, Bandra (W), Pin Code - 400050 Bandra W- Opp Elco Market Soney Apartment, 45, Hill Road, Opp. -

9. Environmental and Social Impact Assessment

TECHNO-ECONOMIC SURVEY AND PREPARATION OF DPR FOR PANVEL-DIVA-VASAI-VIRAR CORRIDOR 9. ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT 9.1 ENVIRONMENTAL BASELINE DATA The main aim of the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) study is to ascertain the existing baseline conditions and to assess the impacts of all the factors as a result of the proposed New Sub-urban corridor on Virar-Vasai Road-Diva-Panvel section. The changes likely to occur in different components of the environment viz. Natural Physical Resources, Natural Ecological (or Biological) Resources, Human/Economic Development Resources (Human use values), Quality of life values (socio-economic), would be studied and assessed to a reasonable accuracy. The environment includes Water Quality, Air Quality, Soils, Noise, Ecology, Socio-economic issues, Archaeological /historical monuments etc. The information presented in this section stems from various sources such as reports, field surveys and monitoring. Majority of data on soil, water quality, air and noise quality, flora and fauna were collected during field studies. This data have been further utilized to assess the incremental impact, if any, due to the project. The development/compilation of environmental baseline data is essential to assess the impact on environment due to the project. The proposed new suburban corridor from Panvel to Virar is to run along the existing Panvel-Diva-Vasai line of Central Railway and then Vasai Road to Virar to Western Railway.The corridor is 69.50 km having 24 stations on Panvel-Virar section. Land Environment The project area is situated in Mumbai, the commercial capital of India. The average elevation of Mumbai plains is 14 m above the mean sea level. -

Factors Affecting Residential Satisfaction in Slum Rehabilitation Housing in Mumbai (As Shown in Table 1)

sustainability Article Factors Affecting Residential Satisfaction in Slum Rehabilitation Housing in Mumbai Bangkim Kshetrimayum 1,2 , Ronita Bardhan 1,3,* and Tetsu Kubota 2 1 Centre for Urban Science and Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, Powai, Mumbai 400076, India; [email protected] 2 Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation, Hiroshima University, 1-5-1 Kagamiyama, Higashi-Hiroshima, Hiroshima 739-8529, Japan; [email protected] 3 Department of Architecture, University of Cambridge, 1-5 Scroope Terrace, Cambridge CB2 1PX, UK * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: 01223-332969 Received: 1 February 2020; Accepted: 12 March 2020; Published: 17 March 2020 Abstract: Affordable housing for the low-income population, who mostly live in slums, is an endemic challenge for cities in developing countries. As a remedy for the slum-free city, most of the major metropolis are resorting to slum rehabilitation housing. Rehabilitation connotes the improved quality of life that provides contentment, yet what entails residential satisfaction in such low-income situations remains a blind spot in literature. The study aims to examine the factors affecting residential satisfaction of slum rehabilitation housing in Mumbai, India. Here, the moderation effects of sociodemographic characteristics between residential satisfaction and its predictors are elaborated using a causal model. Data on residents’ perception of the residential environment were collected from 981 households in three different slum rehabilitation housing areas spatially spread across Mumbai. The causal model indicated that residential satisfaction was significantly determined by internal conditions of dwelling resulting from design, community environment and access to facilities. Gender, age, mother tongue, presence of children, senior citizens in the family, and education moderate the relationship between residential satisfaction and its predictors. -

From Bombay to Mumbai

Travelogue Armchair travels From Bombay to Mumbai This learning reminiscence discussion with six senior citizens from Eudora, Missouri, explores a different travel destination each month with things to learn, questions to answer, and a whole lot of fun along the way. This month they are traveling to Mumbai, India, to immerse themselves in the Indian culture. Traveling How-To’s & Tips • This is a copy of the complete trip for the facilitator to use. This activity can be acted out or read aloud in a skit-like manner by participants representing the six different Front Porch characters using this large-print dialogue. • Check out the links in the article for additional information to bring to the activity. • This PDF slide presentation may be better suited as a stand-alone activity for some audiences. The presenter can refer to the facilitator copy of the complete trip for links and more information to add as the slides are reviewed. • Post a sign announcing the trip. • If your group isn’t familiar with the Front Porch Travelers, have them Meet the McGivers (and friends). A Travel Advisory from Nell and Truman: If using all the information in Travelogue seems too complex for your group, trim it back and just present sections—such as showing and discussing the slide show or copies of the pictures, reading and discussing trivia points, or asking and discussing questions from the Discussion Starters. From Bombay to Mumbai Introduction India is a land of mystery and intrigue—so many sights, sounds, and smells (some good and some not so good). -

Mumbai Street Shopping

Shops Mumbai Street Shopping Colaba Causeway: The everyday carnival that is the Colaba Causeway market is a shopping experience like no other in Mumbai. Geared especially towards tourists, that infamous Indian saying of "sab kuch milega" (you'll get everything) certainly applies at this market. Dodge persistent balloon and map sellers, as you meander along the sidewalk and peruse the stalls. Want your name written on a grain of rice? That's possible too. If you need a break from shopping, pop into Leopold's Cafe or Cafe Mondegar, two well-known Mumbai hangouts. Location: Colaba Causeway, Colaba, south Mumbai. Opening Hours: Daily from morning until night. What to Buy: Handicrafts, books, jewelry, crystals, brass items, incense, clothes. Chor Bazar: Navigate your way through crowded streets and crumbling buildings, and you'll find Chor Bazaar, nestled in the heart of Muslim Mumbai. This fascinating market has a history spanning more than 150 years. Its name means "thieves market", but this was derived from the British mispronunciation of its original name of Shor Bazaar, "noisy market". Eventually stolen goods started finding their way into the market, resulting in it living up to its new name! Location: Mutton Street, between S V Patel and Moulana Shaukat Ali Roads, near Mohammad Ali Road in south Mumbai. Opening Hours: Daily 11 a.m. until 7.30 p.m., except Friday. The Juma Market is held there on Fridays. What to Buy: Antiques, bronze items, vintage items, trash & treasure, electronics item. Linking Road: A fusion of modern and traditional, and East meets West, in one of Mumbai’s hippest suburbs. -

ATRIA the Millennium Mall

https://www.propertywala.com/atria-the-millennium-mall-mumbai ATRIA The Millennium Mall - Worli, Mumbai Commercial Showrooms ATRIA,The Millennium Mall is a shopper's destination, situated next to Nehru Planetarium in the heart of Mumbai City on Dr. Annie Beasant road, Worli. Project ID : J919076951 Builder: ATRIA Properties: Shops, Showrooms Location: ATRIA The Millennium Mall, Worli, Mumbai (Maharashtra) Completion Date: Aug, 2009 Status: Completed Description ATRIA,The Millennium Mall is a shopper's destination, situated next to Nehru Planetarium in the heart of Mumbai City on Dr. Annie Beasant road, Worli. The proposed Bandra-Worli sea link expressway integrates into main traffic at this location offering the project maximum visibility and connectivity. The Mall is a five level complex consisting of Shopping, Entertainment, Food & Leisure catering to the needs of both middle & upper middle class of urban people consisting of various choices of retail outlets and showrooms that will offer an exclusive array of products.The Ground, I, II & III levels will consist of Large Showrooms, Departmental Stores with a variety of national and international brands. While on IVth level of the complex is Entertainment with Video Games, Pool, Bowling alley and the Food Court right below the sky light. Features: 330 Feet expanse and 24 feet high clear glass frontage for showrooms Full height Granite / Marble / Glass in and around entrance and lift lobbies High capacity surround glass elevators & escalators High performance tinted and glass facade Restaurant Discotheque Ideal floor to floor height Permanent stone cladding on external envelope Flame finish granite on external paving Entertainment Zone Separate service lifts 1,00,000 sq. -

State City Store Front Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI Imagine 001-002, KOTIA NIRMAN, NEXT to MERCEDEZ

State City Store Front Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 NEXT TO MERCEDEZ BENZ MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI iMagine 001-002, KOTIA NIRMAN, SHOWROOM NEW LINK ROAD, ANDHERI WEST, MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI iStore by Reliance Digital SHOP NO G 37, GF,R CITY CENTER MALL, LBS MARG, GHATKOPAR (W), KARNATAKA BENGALURU iStore by Reliance Digital 46TH CROSS, 11TH MAIN, 5TH BLOCK, JAYANAGAR KARNATAKA BENGALURU IMAGINE @ U.B.CITY LEVEL 2 THE COLLECTION U.B. CITY, VITTAL MALLYA ROAD KARNATAKA BENGALURU IMAGINE @ FORUM MALL #210, SECOND FLOOR THE FORUM MALL 21 HOSUR ROAD MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI iMagine F-58,LEVEL 1, INORBIT MALL LINK ROAD, MALAD (W) KARNATAKA BENGALURU iStore by Reliance Digital #87, ALMAS CENTER MG ROAD ANDHRA PRADESH HYDERABAD iStore by Reliance Digital SHOP # 1, GROUND FLOOR ASHOKA METROPOLITAN MALL ROAD NO 1, BANJARA HILLS GUJARAT AHMEDABAD iMagine 104,HIMALAYA MALL, NEAR GURUKUL DRIVE-IN ROAD TAMIL NADU CHENNAI IMAGINE @ AMPA SKYWALK SHOP NO. 101A, FIRST FLOOR AMPA SKYWALK NO. 1, NELSON MANICKAM ROAD, MGF METROPOLITAN MALL HARYANA GURGAON iMagine 36-37,II FLOOR, ,M.G.ROAD MAHARASHTRA PUNE iStore by Reliance Digital SHOP NO G 3, UPPER GROUND FLOOR, MILLENNIUM PLAZA,FC ROAD, MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI iStore by Reliance Digital SHOP NO S 12B, SECOND FLOOR, HIGH STREET PHOENIX, SHOP NO UG 2,UPPER GROUND NEAR CADBURY COMPOUND,OFF MAHARASHTRA THANE iStore by Reliance Digital FLOOR,KORUM MALL, EASTERN EXPRESS HIGHWAY, LINKING ROAD,T P S III, BANDRA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI Maple SHOP NO. SB0102 & C2,PLOT NO. 284, KAMAL APT,( BELOW C.C.D.), WEST IWORLD BUSINESS SOLUTIONS PVT NEW DELHI NEW DELHI LTD UB-2 BUNGLOW ROAD, KAMLA NAGAR IWORLD BUSINESS SOLUTIONS PVT NEW DELHI NEW DELHI LTD SHOP NO. -

Tamil Blu Ray Video Songs 1080P Hd 51

1 / 2 Tamil Blu Ray Video Songs 1080p Hd 5.1 Eyes Wide Shut is a 1999 erotic mystery psychological drama film directed, produced and ... The uncut version has since been released in DVD, HD DVD and Blu-ray Disc ... Kubrick invited his friend Michael Herr, who helped write Full Metal Jacket, ... Another track in the orgy, "Migrations", features a Tamil song sung by .... Ip Man: Kung Fu Master 2020 English 720p BluRay ESubs 798MB | 260MB Download. ... IMDB Ratings: 5.1/10. Directed: ... Movie Quality: 720p BluRay ... Torbaaz 2020 Hindi 1080p NF HDRip ESubs 1950MB Download ... Ameesha Fashion Shoot 2020 EightShots Originals Hindi Video 720p HDRip 68MB .... Endhiran Irumbile oru Idhaiyam -1080p- Bluray-Full HD video song - 5.1.mkv. By Ruthra . 1080p HD 5k Video Songs DownloaD Tamil MN .... (1,311)IMDb 8.82h 29min2020X-RayUHD16+. Inspired by ... Story is full of false facts. Back in ... APARNA BALAMURALI, No one could say her first Tamil movie.. Telugu Hd Video Songs 1080p Blu Ray 5.1 Dts Free Download. 1 / 3 ... 3D 1080P HD Blu Ray Movies Free Download in Tamil, Telugu, Hindi,.. Tags: Tamil Bluray Songs 1080p Hd 5.1 Full Movie download, Tamil Bluray Songs ... Download tamil hd video songs 1080p blu ray latest 5.1 2014 MP3 and . hd .... Endhiran irumbile oru idhaiyam bluray full hd video song 5 1 mkv songs sung by ... Tamil blu ray video songs DTS 5.1 Surround Sound MS CREATIONS HD ... Tamil Hd Video Songs 1080p Blu Ray Latest 5.1 2015 Calendar >> . Free Tamil Bluray Video Songs 1080p Mkv Download mp3 .