First Nations Environmental Water Guidance Project MLDRIN Member Nations 2020-21 Priorities Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 8. Aboriginal Water Values and Uses

Chapter 8. Aboriginal water values and uses Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning 8. Aboriginal water values and uses The Murray-Darling Basin Plan requires Basin states to identify objectives and outcomes of water, based on Aboriginal values and uses of water, and have regard to the views of Traditional Owners on matters identified by the Basin Plan. Victoria engaged with Traditional Owner groups in the Water Resource Plan for the northern Victoria area to: • outline the purpose, scope and opportunity for providing water to meet Traditional Owner water objectives and outcomes through the Murray-Darling Basin Plan • define the role of the water resource plans in the Basin, including but not limited to the requirements of the Basin Plan (Chapter 10, Part 14) • provide the timeline for the development and accreditation of the Northern Victoria Water Resource Plan • determine each Traditional Owner group’s preferred means of engagement and involvement in the development of the Northern Victoria Water Resource Plan • continue to liaise and collaborate with Traditional Owner groups to integrate specific concerns and opportunities regarding the water planning and management framework. • identify Aboriginal water objectives for each Traditional Owner group, and desired outcomes The Water Resource Plan for the Northern Victoria water resource plan area, the Victorian Murray water resource plan area and the Goulburn-Murray water resource plan area is formally titled Victoria’s North and Murray Water Resource Plan for the purposes of accreditation. When engaging with Traditional Owners this plan has been referred to as the Northern Victoria Water Resource Plan and is so called in Chapter 8 of the Comprehensive Report. -

Lake Victoria Annual Report 2008-09 Murray–Darling Basin Authority Lake Victoria Annual Report 2008-09

MURRAY-DARLING BASIN AUTHORITY Lake Victoria Annual Report 2008-09 Murray–Darling Basin Authority Lake Victoria Annual Report 2008-09 Published by Murray-Darling Basin Authority Postal Address GPO Box 1801, Canberra ACT 2601 Office location Level 4, 51 Allara Street, Canberra City Australian Capital Territory Telephone (02) 6279 0100 international + 61 2 6279 0100 Facsimile (02) 6248 8053 international + 61 2 6248 8053 E-Mail [email protected] Internet http://www.mdba.gov.au For further information contact the Murray-Darling Basin Authority office on (02) 6279 0100 This report may be cited as: Lake Victoria Annual Report 2008-09. MDBA Publication No. 50/09 ISBN: 978-1-921557-56-9 (on-line) ISBN: 978-1-921557-57-6 (print) © Copyright Murray-Darling Basin Authority (MDBA), on behalf of the Commonwealth of Australia 2009. This work is copyright. With the exception of photographs, any logo or emblem, and any trademarks, the work may be stored, retrieved and reproduced in whole or in part, provided that it is not sold or used in any way for commercial benefit, and that the source and author of any material used is acknowledged. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 or above, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Attorney General’s Department, National Circuit, Barton ACT 2600 or posted at http://www.ag.gov.au/cca. The views, opinions and conclusions expressed by the authors in this publication are not necessarily those of MDBA or the Commonwealth. -

The Archaeology of Mootwingee, Western New South Wales

AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS McCarthy, Frederick D., and N. W. G. Macintosh, 1962. The archaeology of Mootwingee, western New South Wales. Records of the Australian Museum 25(13): 249–298, plates 19–27. [3 December 1962]. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.25.1962.665 ISSN 0067-1975 Published by the Australian Museum, Sydney nature culture discover Australian Museum science is freely accessible online at http://publications.australianmuseum.net.au 6 College Street, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia VOL. XXV, No. 13 SYDNEY, 3 DECEMBER, 1962 RECORDS of The Australian Museulll (World List abbreviation: Rec. Au.t. Mu •• ) Printed by order of the Trustees Edited by the Director, J. W. EVANS, Sc.D. The Archaeology of Mootwingee, Western New South Wales By F. D. McCARTHY and N. W. G. MACINTOSH Pages 249-298. Plates XIX·XXVII Figs. 1-9 Registered at the General Post Office. Sydney, for transmiRsion by post as a periodical G 316QO 249 The Archaeology of Mootwingee, Western New South Wales BY F. D. McCarthy, Australian Museum and N. W. G. Macintosh, University of Sydney (Figs. 1-9) (Plates XIX-XXVII) Manuscript received 20.9.61 PREVIOUS LITERATURE The rock engravings in the main gallery, and the paintings in the" Big Cave", have been described briefly, and some of the main carvings and paintings illustrated, by Pulleine (1926), Riddell (1928), Barrett (1929 and 1943), Davidson (1936), Black (1943 and 1949), and McCarthy (1957 and 1958). Pulleine's claim (op. cit. 80) that he recorded all of the motifs at Mootwingee is far from being the case. These papers indicated that Mootwingee was an important comparative site on the eastern extremity of the full intaglio pecking technique, and a complete recording was therefore decided upon. -

FPA Legislation Committee Tabled Docu~Ent No. \

FPA Legislation Committee Tabled Docu~ent No. \, By: Mr~ C'-tn~:S AOlSC, Date: b IV\a,c<J..-. J,od.D , e,. t\-40.M I ---------- - ~ -- Australian Government National IndigeJrums Australlfans Agency OFFICIAL Chief Executive Officer Ray Griggs AO, CSC Reference: EC20~000257 Senator Tim Ayres Labor Senator for New South Wales Deputy Chair, Senate Finance and Public Administration Committee 6 March 2020 Re: Additional Estimates 2019-2020 Dear Senatafyres ~l Thank you for your letter dated 25 February 2020 requesting information about Indigenous Advancement Strategy (IAS) and Aboriginals Benefit Account (ABA) grants and unsuccessful applications for the periods 1 January- 30 June 2019 and 1 July 2019 (Agency establishment) - 25 February 2020. The National Indigenous Australians Agency has prepared the attached information; due to reporting cycles, we have provided the requested information for the period 1 January 2019 - 31 January 2020. However we can provide the information for the additional period if required. As requested, assessment scores are provided for the merit-based grant rounds: NAIDOC and ABA. Assessment scores for NAIDOC and ABA are not comparable, as NAIDOC is scored out of 20 and ABA is scored out of 15. Please note as there were no NAIDOC or ABA grants/ unsuccessful applications between 1 July 2019 and 31 January 2020, Attachments Band D do not include assessment scores. Please also note the physical location of unsuccessful applicants has been included, while the service delivery locations is provided for funded grants. In relation to ABA grants, we have included the then Department's recommendations to the Minister, as requested. -

Yuranga Aboriginal Network Mildura Local Aboriginal Network

YURANGA ABORIGINAL NETWORK MILDURA LOCAL ABORIGINAL NETWORK COMMUNITY PLAN 2020 OFFICIAL ACKNOWLEDGEMENT AND RESPECT TELKI NGAWINGI (Latji Latji for Good Day) We would like to take this opportunity to acknowledge the traditional owners of this Country and the Elders who have passed into the Dreaming and Elders present today who have survived the impacts of Colonisation. Our Elders are the Cornerstone of our communities and we pay our Respect to them, their journeys, their strength and their Resilience. If it were not for them, we would not be here. OFFICIAL The Yuranga Local Aboriginal Network in Mildura was established in 2008, as part of the then Victorian Government’s New Representative Arrangement for Aboriginal People living in Victoria. The LAN’s original Community Plan was Titled: “The Mildura Local Indigenous Network – The Yuranga Aboriginal Committee, Community Plan.” It’s overarching framework was the VIAF of the time. Local Aboriginal Networks (LANs) bring Aboriginal people together to set priorities develop community plans and improve social connection. Our Mildura LAN has an Aboriginal name, which means “bend in the river.” The LAN in Mildura has been active within the Mildura community and over the years has held a number of Projects and supported others, however we have worked with the local Mildura Rural City Council and have produced a video that sits on the AV Website. MRCC have endorsed our Community Plan and it also sits on their Website along with all of the Geographical Community Plans, as the Municipality’s first Cultural Plan. Our LAN now has approximately 212 participants and there are 39 LANs in the State of Victoria. -

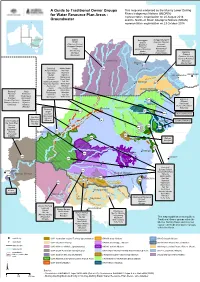

A Guide to Traditional Owner Groups For

A Guide to Traditional Owner Groups Th is m ap w as e nd orse d by th e Murray Low e r Darling Rive rs Ind ige nous Nations (MLDRIN) for Water Resource Plan Areas - re pre se ntative organisation on 20 August 2018 Groundwater and th e North e rn Basin Aboriginal Nations (NBAN) re pre se ntative organisation on 23 Octobe r 2018 Bidjara Barunggam Gunggari/Kungarri Budjiti Bidjara Guwamu (Kooma) Guwamu (Kooma) Bigambul Jarowair Gunggari/Kungarri Euahlayi Kambuwal Kunja Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Mandandanji Mandandanji Murrawarri Giabel Bigambul Mardigan Githabul Wakka Wakka Murrawarri Githabul Guwamu (Kooma) M Gomeroi/Kamilaroi a r a Kambuwal !(Charleville n o Ro!(ma Mandandanji a GW21 R i «¬ v Barkandji Mutthi Mutthi GW22 e ne R r i i «¬ am ver Barapa Barapa Nari Nari d on Bigambul Ngarabal C BRISBANE Budjiti Ngemba k r e Toowoomba )" e !( Euahlayi Ngiyampaa e v r er i ie Riv C oon Githabul Nyeri Nyeri R M e o r Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Tati Tati n o e i St George r !( v b GW19 i Guwamu (Kooma) Wadi Wadi a e P R «¬ Kambuwal Wailwan N o Wemba Wemba g Kunja e r r e !( Kwiambul Weki Weki r iv Goondiwindi a R Barkandji Kunja e GW18 Maljangapa Wiradjuri W n r on ¬ Bigambul e « Kwiambul l Maraura Yita Yita v a r i B ve Budjiti Maljangapa R i Murrawarri Yorta Yorta a R Euahlayi o n M Murrawarri g a a l rr GW15 c Bigambul Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Ngarabal u a int C N «¬!( yre Githabul R Guwamu (Kooma) Ngemba iv er Kambuwal Kambuwal Wailwan N MoreeG am w Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Wiradjuri o yd Barwon River i R ir R Kwiambul !(Bourke iv iv Barkandji e er GW13 C r GW14 Budjiti -

Aboriginal Community Profile Series BULOKE Local Government Area

Aboriginal community profile series BULOKE Local Government Area Overview Population in 2011 35 19 Aboriginal people Median age 6,170 48 non-Aboriginal people Median age Aboriginal organisations Known Traditional Owners Barengi Gadjin Land Council Aboriginal Corporation# Dja Dja Wurrung Clans Aboriginal Corporation# The Life Course Approach Wadi Wadi Wemba Wamba Barapa Barapa First Nations to Aboriginal Affairs in Victoria Aboriginal Corporation Key community groups The Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework 2013-2018 Northern Loddon Mallee Indigenous Family Violence is the Government’s plan for closing the gap in Victoria Regional Action Group by 2031, working in partnership with Aboriginal Loddon Mallee Regional Aboriginal Justice Advisory communities, service providers and the business sector. Committee As the Aboriginal population in the Buloke Local Loddon Mallee Closing the Health Gap Advisory Government Area (LGA) comprises less than 50 Committee people, this profile is limited to acknowledging Please refer to “Victoria” profile for a list of statewide Aboriginal Aboriginal organisations in the area and organisations, as these may be active in this LGA. Also note there cultural heritage. may be other Aboriginal organisations and community groups which operate in this area. The profile is intended to support conversations #Registered Aboriginal Party covering a specific area within the LGA. between communities, service providers, governments and other key stakeholders. The information can help inform approaches and action at the local level to better meet the needs of Aboriginal people and deliver improved health, education, and employment outcomes. Cultural heritage Buloke LGA Aboriginal people have a deep and continuous connection to the place now called Victoria, evidenced by the number of statewide cultural heritage places. -

Groundwater) Groundwater Water Resource Plan Area Nations Groundwater Water Resource Plan Area Nations GW1 Ngunnawal/Ngunawal GW11 Cont

A Guide to Traditional Owner Groups for Water Resource Plan Areas (Groundwater) Groundwater Water Resource Plan Area Nations Groundwater Water Resource Plan Area Nations GW1 Ngunnawal/Ngunawal GW11 cont. Kunja Australian Capital Territory (groundwater) Wolgalu Kwiambul Ngambri Maljangapa Ngarigu Maraura GW2 Dhudhuroa Murrawarri Goulburn-Murray Dja Dja Wurrung Mutthi Mutthi Taungurung Nari Nari Waywurru Ngarabal Yaithmathang Ngemba Yorta Yorta Ngiyampaa GW3 Dja Dja Wurrung Nyeri Nyeri Wimmera-Mallee (groundwater) Latji Latji Tati Tati Ngintait Wadi Wadi Tati Tati Wailwan Wemba Wemba Wemba Wemba Watjobaluk Weki Weki Wergaia Wiradjuri GW4 First Peoples of the South East Yita Yita South Australian Murray Region Maraura Yorta Yorta Ngaduri GW12 Wailwan Ngarrindjeri Macquarie-Castlereagh Alluvium Wiradjuri Ngintait G13 Barkandji Peramangk NSW Great Artesian Basin Shallow Bigambul RMMAC Budjiti GW5 Kaurna Euahlayi Eastern Mount Lofty Ranges Peramangk Gomeroi/Kamilaroi GW6 Barkandji Guwamu (Kooma) NSW Murray-Darling Basin Porous Rock Barapa Barapa Kambuwal Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Kunja Maraura Kwiambul Mutthi Mutthi Maljangapa Nari Nari Murrawarri Ngarabal Ngarabal Ngiyampaa Ngemba Nyeri Nyeri Wailwan Tati Tati Wiradjuri Wadi Wadi GW14 Namoi Alluvium Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Wemba Wemba GW15 Gwydir Alluvium Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Weki Weki GW18 Bigambul Wiradjuri NSW Border Rivers Alluvium Githabul Yorta Yorta Kambuwal GW7 Barkandji Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Darling Alluvium Budjiti Kwiambul Euahlayi GW19 Bigambul Murrawarri Queensland Border Rivers - Moonie Githabul -

Meeting Update Murray Lower Darling Rivers Indigenous Nations

Meeting Update Murray Lower Darling Rivers Indigenous Nations Meeting Details: MLDRIN and NBAN Joint Meeting Date: 15th and 16th March 2018 Venue: Commercial Hotel, Dubbo NSW Attendance Members: Kingsley Abdulla, Gary Abdulla (Maraura), Stephen Atkinson (Wadi Wadi), Wayne Carr, Coral Peckham, Peter Ingram (Wiradjuri), Janice Freeman-Williams, Alice Williams (Wolgalu), Bella Kennedy, Stewart Taylor (Wamba Wamba), Brendan Kennedy (Tati Tati), Badger Bates, Warren Clarke (Barkandji), Ricky Kirby (Muthi Muthi), Monica Morgan, Lance James (Yorta Yorta), Grant Rigney (Ngarrindjeri), Neville Whyman (Barapa Barapa), Rene Woods, Ian Woods (Nari Nari), Observers: Jason Johnson, Christine Abdulla (River Murray and Mallee Aboriginal Corporation), Lavinus Ingram (Wadi Wadi), Jenny Munroe (Wiradjuri), Damein Bell (Gunditjmara – Facilitator) Key issues discussed: • The key purpose of the meeting was to review three reports arising from the National Cultural Flows Research Project. These reports are the product of over five years of work by First Nations, in partnership with hydrologists, water planners and legal academics . • The combined MLDRIN/NBAN group reviewed three reports: 1) The final summary report for the project: Dungala Baake, re-thinking the Future of Water Management in Australia, 2) A summary report on the options for legal and policy reform to give effect to Cultural Flows, A Pathway to Cultural Flows in Australia and 3) Cultural Flows, a Guide for Community. • Delegates expressed a wish to undertake further consultation within the Nation groups about the draft reports. Extensive discussions were held about the content and key feedback was captured. Delegates agreed to a process for progressing final amendments to the drafts (see below). • The Cultural Flows reports are a major contribution to Water Reform in Australia, working towards a future where Aboriginal water rights are embedded in Australia’s water entitlement and management framework. -

Indigenous Knowledge in the Built Environment a Guide for Tertiary Educators

Indigenous Knowledge in The Built Environment A Guide for Tertiary Educators David S Jones, Darryl Low Choy, Richard Tucker, Scott Heyes, Grant Revell & Susan Bird Support for the production of this publication has been 2018 provided by the Australian Government Department of Education and Training. The views expressed in this report do ISBN not necessarily reflect the views of the Australian Government 978-1-76051-164-7 [PRINT], Department of Education and Training. 978-1-76051-165-4 [PDF], With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and 978-1-76051-166-1 [DOCX] where otherwise noted, all material presented in this document is provided under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 Citation: International License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Jones, DS, D Low Choy, R Tucker, SA Heyes, G Revell & S Bird by-sa/4.0/ (2018), Indigenous Knowledge in the Built Environment: A Guide The details of the relevant licence conditions are available on for Tertiary Educators. Canberra, ACT: Australian Government the Creative Commons website (accessible using the links Department of Education and Training. provided) as is the full legal code for the Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike 4.0 International License http:// Warning: creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are warned that the following document may contain images and names of Requests and inquiries concerning these rights should be deceased persons. addressed to: Office for Learning and Teaching A Note on the Project’s Peer Review Process: Department of Education The content of this teaching guide has been independently GPO Box 9880, peer reviewed by five Australian academics that specialise Location code N255EL10 in the teaching of Indigenous knowledge systems within the Sydney NSW 2001 built environment professions, two of which are Aboriginal [email protected] academics and practitioners. -

Respecting Country

Respecting Country At PeeKdesigns we have had the privilege to work on several education and community projects involving First Peoples / Aboriginal culture. We are extremely passionate about helping local Indigenous communities engage the general public and believe that as part of reconciliation, learning about Australia’s First Peoples’ should be a priority in all Australian schools. The cultural resources we create are undertaken in partnership with the Traditional Owners, Elders, educators and co-management committees of the local region. Understanding that Aboriginal culture is a complex society based around respect and the responsibilities that entails, helps us create resources that embrace the ideology of the local communities. • Respect for Country and the mother who provides for the peoples needs. • Respect for the ancestors, the Dreaming and the creator/s. • Respect for the Elders, both past and present. • Respect for people including family, others and oneself. • Respect for knowledge, culture, traditions and social structure including kinship. Some of the Aboriginal communities we have had the privilege to work with through our various employments include: the Gamilaroi, Uallaroi, Wiradjuri, Ngarigo, Bangerang, Wamba Wamba and Barapa Barapa people of New South Wales; the Warumungu, Alyawarre and Warlpiri people from the Northern Territory; the Gunaikurnai and Taungurung people of Victoria; the Pitjantjatjara people of South Australia; and the Noongar people of Western Australia. www.peekdesigns.com.au Publications Published Coleman, K. McKemey, M. and Coleman, P. (2017) Narran Lake Nature Reserve Education Package. Narran Lake Nature Reserve Co-Management Committee in partnership with NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. Coleman, K. (2017) Sculptures in the Scrub Education Package. -

BCAC Reasons for Decision 15 June 2021 Pdf 427.42 KB

STATEMENT OF REASONS FOR THE DECISION OF THE VICTORIAN ABORIGINAL HERITAGE COUNCIL IN RELATION TO AN APPLICATION BY BARAPA COUNTRY ABORIGINAL CORPORATION DATE OF DECISION: 15 June 2021 1. Decision The Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council (Council) has declined the application of the Barapa Country Aboriginal Corporation (BCAC), to be a Registered Aboriginal Party (RAP) under the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006 (Act). 2. Decision Area The attached map (Attachment 1) depicts the area that BCAC sought to be a RAP over (Decision Area). The area extends from Fish Point (on the Murray river to the north), extending along the Murray River to Robertson’s Bend to the east of Cohuna, across to Cohuna. The boundary follows the western side of Know Swamp to Kotta, heads west to Lake Marmal (excluding Boort), continues west to just beyond the Avoca River, then north towards Lake Boga (although excluding it) and Fish Point. The Decision Area borders with two neighbouring RAPs – the Yorta Yorta to the East and Dja Dja Wurrung to the South. 3. Findings of Fact and Evidence Part 10 of the Act requires that Council consider a number of matters in making a decision. Council considered the application in light of these matters. In relation to the Decision Area, Council made the following findings of fact, based on the evidence and other material detailed below. a. Native Title (s 151(2) of the Act) Council noted BCAC is not a registered native title holder for the Decision Area. Council also noted there is no other registered native title holder for the Decision Area.