School Integration in Massachusetts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Review of Standardized Testing Practices and Perceptions in Maine

A Review of Standardized Testing Practices and Perceptions in Maine Janet Fairman, Ph.D. Amy Johnson, Ph.D. Ian Mette, Ph.D Garry Wickerd, Ph.D. Sharon LaBrie, M.S. April 2018 Maine Education Policy Research Institute Maine Education Policy Research Institute McLellan House, 140 School Street 5766 Shibles Hall, Room 314 Gorham, ME 04038 Orono, ME 04469-5766 207.780.5044 or 1.888.800.5044 207.581.2475 Published by the Maine Education Policy Research Institute in the Center for Education Policy, Applied Research, and Evaluation (CEPARE) in the School of Education and Human Development, University of Southern Maine, and the Maine Education Policy Research Institute in the School of Education and Human Development at the University of Maine at Orono. The Maine Education Policy Research Institute (MEPRI), is jointly funded by the Maine State Legislature and the University of Maine System. This institute was established to conduct studies on Maine education policy and the Maine public education system for the Maine Legislature. Statements and opinions by the authors do not necessarily reflect a position or policy of the Maine Education Policy Research Institute, nor any of its members, and no official endorsement by them should be inferred. The University of Maine System does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, national origin or citizenship status, age, disability, or veteran's status and shall comply with Section 504, Title IX, and the A.D.A in employment, education, and in all other areas of the University. The University provides reasonable accommodations to qualified individuals with disabilities upon request. -

Dual County League

Central (Leslie C) Dual County League: Acton Boxborough Regional High School, Bedford High School, Concord Carlisle High School, Lincoln Sudbury Regional High School, Wayland High School, Weston High School, Westford High School (7 schools) Central League: Advanced Math and Science Academy Auburn High School Assabet Valley Tech Regional High School Baypath Regional Vocational Tech High School Blackstone Valley Tech, Doherty Worcester Public Schools Grafton High School Nipmuc High School Northbridge High School Montachusett Reg Vocational Tech School, Fitchburg Nashoba Valley Tech, Westford, MA St. Bernard High School St. Peter Marion High School Notre Dame Academy Worcester (13 Schools) Mid Wachusett League: Algonquin Regional High School, Bromfield High School, Fitchburg High School, Groton Dunstable High School, Hudson High School, Leominster High School, Littleton High School, Lunenburg High School, Marlborough High School, Nashoba Regional High School, North Middlesex Regional High School, Oakmont Regional High School, Shepherd Hill Regional High School, Shrewsbury High School, Tahanto Regional High School, Tyngsborough Regional High School, Wachusett Regional High School, Westborough High School (18 Schools) Independent Eastern League (IEL): Bancroft School (Worcester), Concord Academy (Concord) (2) Independent School League (ISL): Concord Academy, Cushing Academy, Groton School, Lawrence Academy, Middlesex School, Rivers School, St. Mark’s School (8 Schools) Private School Programs: Applewild School (Fitchburg), Charles River School (Dover), Fay School (Southboro), Nashoba Brooks School (Concord), Meadowbrook School (Weston), Winchendon Academy (Winchendon), Worcester Academy (Worcester) (7 Schools) (55 Schools Total) . -

BLSA Begins Alumni Speaker Series BPS Suspends Admissions For

Volume LXIII THEARGO MARCH 2021 THE OFFICIAL NEWSPAPER OF THE BOSTON LATIN SCHOOL BPS Suspends Admissions for AWC By Elyssa Cabey (III) While some agree with the & Kevin Zhong (IV) plan to establish a temporary hi- atus for the AWC admissions re- Staff Writers quirement, others have expressed concerns about the exam’s sus- On February 3, the Boston pension. Some members of the School Committee voted to tem- Boston Latin School communi- porarily suspend the admissions ty believe that limiting access to test for the Boston Public Schools AWC may hinder younger stu- (BPS) Advanced Work Class dents’ learning and negatively af- (AWC) program set to take place fect their preparation for entrance during the 2021-2022 school into exam schools. year. Ms. Monica Gribaudo, a BLS The AWC program provides Algebra teacher, believes that the an accelerated academic curricu- AWC program should be expand- lum for fourth- to sixth-grade stu- ed to more students who wish to dents in BPS. In previous years, challenge themselves, without students were admitted to the pro- isolating a select group for the ac- gram based on their performance celerated coursework. on the TerraNova exam, which is “I really don’t like seeing administered to third-grade stu- a child bored in the classroom. dents throughout the district. Stu- I think that if there’s a group of dents who earned a benchmark them that could go at a little faster score on the exam would then be pace and don’t need to have things picked via a lottery system to de- repeated to them 18 times, then termine admission into the AWC Kelly Kate sure, put those kids together. -

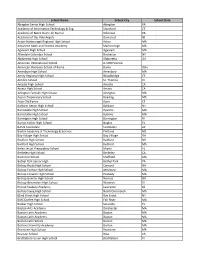

Participating School List 2018-2019

School Name School City School State Abington Senior High School Abington PA Academy of Information Technology & Eng. Stamford CT Academy of Notre Dame de Namur Villanova PA Academy of the Holy Angels Demarest NJ Acton-Boxborough Regional High School Acton MA Advanced Math and Science Academy Marlborough MA Agawam High School Agawam MA Allendale Columbia School Rochester NY Alpharetta High School Alpharetta GA American International School A-1090 Vienna American Overseas School of Rome Rome Italy Amesbury High School Amesbury MA Amity Regional High School Woodbridge CT Antilles School St. Thomas VI Arcadia High School Arcadia CA Arcata High School Arcata CA Arlington Catholic High School Arlington MA Austin Preparatory School Reading MA Avon Old Farms Avon CT Baldwin Senior High School Baldwin NY Barnstable High School Hyannis MA Barnstable High School Hyannis MA Barrington High School Barrington RI Barron Collier High School Naples FL BASIS Scottsdale Scottsdale AZ Baxter Academy of Technology & Science Portland ME Bay Village High School Bay Village OH Bedford High School Bedford NH Bedford High School Bedford MA Belen Jesuit Preparatory School Miami FL Berkeley High School Berkeley CA Berkshire School Sheffield MA Bethel Park Senior High Bethel Park PA Bishop Brady High School Concord NH Bishop Feehan High School Attleboro MA Bishop Fenwick High School Peabody MA Bishop Guertin High School Nashua NH Bishop Hendricken High School Warwick RI Bishop Seabury Academy Lawrence KS Bishop Stang High School North Dartmouth MA Blind Brook High -

Nine Facts About the SAT That Might Surprise You

Nine Facts About the SAT That Might Surprise You By Lynn Letukas COLLEGE BOARD RESEARCH Statistical Report RESEARCH Executive Summary The purpose of this document is to identify and dispel rumors that are frequently cited about the SAT. The following is a compilation of nine popular rumors organized into three areas: Student Demographics, Test Preparation/Test Prediction, and Test Utilization. Student Demographics Student demographics claims are those that primarily center around a specific demographic group that is said to over-/underperform on the SAT. Presumably, it is reasoned, if the SAT were a fair test, no student demographic characteristics would matter, as average scores would be similar across groups. Therefore, some people assume that any difference in SAT performance by demographics must indicate test bias for/against a demographic group. Rumor 1: The SAT Is a Wealth Test. According to Peter Sacks, author of Standardized Minds, “one can make a good guess about a child’s standardized test scores simply by looking at how many degrees her parents have and what kind of car they drive.”1 This comment is illustrative of frequent criticism that the SAT is merely a “wealth test” because there is a correlation between student scores and socioeconomic status (i.e., parental income and educational attainment). Proponents of this claim often support their arguments by stating that the SAT only covers content that is learned by wealthy students, rather than material covered in high school.2 Fact: Rigorous Course Taking in High School Better Explains Why Students Do Well (or Not) on the SAT. While SAT scores may be correlated with socioeconomic status (parental income and education), correlation does not mean two phenomena are causally related (e.g., parental income causes students to do well on the SAT). -

Public School Admissions and the Myth of Meritocracy: How and Why Screened Public School Admissions Promote Segregation

BUERY_FIN.DOCX(DO NOT DELETE) 4/14/20 8:46 PM PUBLIC SCHOOL ADMISSIONS AND THE MYTH OF MERITOCRACY: HOW AND WHY SCREENED PUBLIC SCHOOL ADMISSIONS PROMOTE SEGREGATION RICHARD R. BUERY, JR.* Public schools in America remain deeply segregated by race, with devastating effects for Black and Latinx students. While residential segregation is a critical driver of school segregation, the prevalence of screened admissions practices can also play a devastating role in driving racial segregation in public schools. New York City, one of the most segregated school systems in America, is unique in its extensive reliance on screened admissions practices, including the use of standardized tests, to assign students to sought-after public schools. These screens persist despite their segregative impact in part because they appeal to America’s embrace of the idea of meritocracy. This Article argues that Americans embrace three conceptions of merit which shield these screens from proper scrutiny. The first is individual merit—the idea that students with greater ability or achievement deserve access to better schools. The second is systems merit—the idea that poor student performance on an assessment is a failure of the system that prepared the student for the assessment. The third is group merit—the idea that members of some groups simply possess less ability. Each of these ideas has a pernicious impact on perpetuating racial inequality in public education. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 102 I. THE APPEAL OF THREE DIMENSIONS OF MERIT .................... 104 A. Merit of the Individual .................................................... 104 B. Merit of the System ......................................................... 107 C. Merit of the Group .......................................................... 109 II. THE MYTH OF MERITOCRACY IN K12 ADMISSIONS ............. -

Rethinking School Accountability: Opportunities for Massachusetts

RETHINKING SCHOOL ACCOUNTABILITY OPPORTUNITIES FOR MASSACHUSETTS UNDER THE EVERY STUDENT SUCCEEDS ACT Senator Patricia D. Jehlen, Chair Senate Sub-committee to the Joint Committee on Education May 2018 The special Senate Subcommittee to the Joint Committee on Education was established per order of the Massachusetts State Senate in February, 2017: Ms. Chang-Díaz presented the following order, to wit: Ordered, That there shall be a special Senate sub-committee to the Joint Committee on Education, to consist of five members from the current Senate membership on the Joint Committee on Education, chaired by the Senate vice chair of the Joint Committee on Education, for the purpose of making an investigation and study of the Commonwealth’s alignment with and opportunities presented by the Every Student Succeeds (ESSA) Act, Public Law 114-95. The subcommittee shall submit its report and related legislation, if any, to the joint committee on Education once its report is completed. Senate Sub-committee chair and report author Senator Patricia D. Jehlen, with gratitude to those who contributed ideas, data, and comments Senate Sub-committee Members: Senator Michael J. Barrett Senator Jason M. Lewis Senator Barbara A. L'Italien Senator Patrick M. O'Connor Staff: Victoria Halal, Matthew Hartman, Emily Wilson, Kat Cline, Dennis Burke, Erin Riley, Sam Anderson, Daria Afshar Sponsored Events: (6/13/17) Panel Discussion: Life & Learning in MA Turnaround Schools https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KbErK6rLQAY&t=2s (12/12/17) Mildred Avenue School Site Visit -

How and Why Standardized Tests Systematically Underestimate

St. John's Law Review Volume 80 Number 1 Volume 80, Winter 2006, Number 1 Article 7 How and Why Standardized Tests Systematically Underestimate African-Americans' True Verbal Ability and What to Do About It: Towards the Promotion of Two New Theories with Practical Applications Dr. Roy Freedle Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/lawreview This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in St. John's Law Review by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RONALD H. BROWN CENTER FOR CIVIL RIGHTS AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT SYMPOSIUM HOW AND WHY STANDARDIZED TESTS SYSTEMATICALLY UNDERESTIMATE AFRICAN-AMERICANS' TRUE VERBAL ABILITY AND WHAT TO DO ABOUT IT: TOWARDS THE PROMOTION OF TWO NEW THEORIES WITH PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS DR. ROY FREEDLEt INTRODUCTION In this Article, I want to raise a number of issues, both theoretical and practical, concerning the need for a total reassessment of especially the verbal intelligence of minority individuals. The issues to be raised amount to a critical reappraisal of standardized multiple-choice tests of verbal intelligence, such as the Law School Admissions Test ("LSAT"). I want to probe very deeply into why such standardized tests systematically underestimate verbal intelligence. This leads me first to review the prospects for a new standardized test of verbal intelligence associated with the studies of Joseph Fagan and Cynthia Holland.1 These studies show us that the races are equal; this result leads us to question the construct validity of many current standardized tests of verbal aptitude. -

Program Time Line for the M.I.A.A

Girls Swimming & Diving North Sectionals Program Time Line for the M.I.A.A. Winter Girls North Sectional Swim & Dive Championships Al and Barrie Zesiger Sports & Fitness Center @ MIT M.I.A.A. Sportsmanship guidelines and behavioral expectations will be strictly enforced throughout the meet. These guidelines specifically prohibit all noisemakers and signs. Shirts must be worn in the spectator gallery at all times and body painting is not allowed. Only school or team banners are allowed and these must be hung by meet staff. Only participants and team staff listed on the roster may be on deck during the meet. 2:45 Swimmers & Coaches check-in at Entrance Hall Lobby to the left of the Balcony Stairs 3:00 Warm-ups begin in the Competition Pool and the Diving Lap Pool. Feet first entries only. TBA Sprint Lanes (One Length). Time and lanes will be announced by the meet referee. 3:15 Balcony open for Spectators 3:15 Officials meeting with divers and dive coaches – beneath the platform diving boards 3:20 – 3:40 Coaches’ Meeting - in the DuPont Entry Hall lobby behind the Diving Board Complex Meet Information, medley relay declarations, scratches, declared false starts, etc. 3:45 Timers meeting. Zesiger Sports Center Lobby. Timers report with watches 4:05 Warm-up Ends. Diving Lap Pool Open. 4:05 Senior introductions (gather at awards area near lane 1). Sportsmanship award presentations. Moment of Silence followed by the National Anthem. 4:15 Winter North Sectional Championship in Swimming & Diving begin - 8 Lane Swimming ----- 15 minute Swim Break in lieu of Diving. -

MASSACHUSETTS- Other Indentified Schools (PDF)

State Name LEA Name LEA NCES ID School Name School NCES ID Reading Proficiency Target Reading Participation Target Math Proficiency Target Math Participation Target Elementary/ Middle School Other Academic Indicator Target Graduation Rate Target State Defined School Improvement Status Title I School MASSACHUSETTS Quabbin 2500001 Quabbin Regional Middle School 250000102003 All All Status 2 Not a Title I school MASSACHUSETTS Quabbin 2500001 Hardwick Elementary 250000102398 All All Status 2 Title I targeted assistance school MASSACHUSETTS Quabbin 2500001 Hubbardston Center 250000102399 All All Status 2 Not a Title I school MASSACHUSETTS Quabbin 2500001 Oakham Center 250000102402 All All Status 2 Not a Title I school MASSACHUSETTS Quabbin 2500001 Ruggles Lane 250000102403 All All Status 2 Title I targeted assistance school MASSACHUSETTS Spencer-E Brookfield 2500002 Wire Village School 250000201859 All All Status 2 Title I targeted assistance school MASSACHUSETTS Southwick-Tolland-Granville Regional School District 2500013 Southwick-Tolland Regional High 250001301782 All All All Status 1 Not a Title I school MASSACHUSETTS Southwick-Tolland-Granville Regional School District 2500013 Woodland Elementary 250001301783 All All Status 2 Title I targeted assistance school MASSACHUSETTS Chesterfield-Goshen 2500014 New Hingham Regional Elementary 250001401275 All All Status 2 Not a Title I school MASSACHUSETTS Academy Of the Pacific Rim Charter Public (District) 2500021 Academy Of the Pacific Rim Charter Public School 250002100511 All All All Status -

2018 Field Hockey Program Cover and Back.Pub

2018 State Field Hockey Division 1 Division 2 Whitman-Hanson Greenfield Regional High School High School Award History 2017 – Division 1 Amherst Pelham Regional High School 2017 – Division 2 Sutton High School 2016 – Division 1 North Middlesex Regional High School 2016 – Division 2 Hull High School 2015 – Division 2 Old Rochester Regional High School 2014 - Division 1 Nashoba Regional High School 2013 – Division 1 Central Catholic High School 2013 – Division 2 David Prouty High School 2011 – Division 1 Springfield Central High School 2010 – Division 1 Oliver Ames High School 2010 – Division 2 Hopedale Jr/Sr High School 2008 – Division 1 Malden High School 2008 – Division 2 Hanover High School 2007 – Division 1 Agawam High School 2007 – Division 2 Littleton High School 2006 – Division 1 Agawam High School 2006 – Division 2 Douglas High School 2005 – Division 1 Stoughton High School 2005 – Division 2 North Reading High School 2004 – Division 1 Shrewsbury High School 2004 – Division 2 Hamilton-Wenham Regional High School 2003 – Division 1 Nashoba Regional High School 2003 – Division 2 North Andover High School 2002 – Division 1 Lawrence High School 2002 – Division 2 R.C. Mahar Regional School The 2018 MIAA Sportsmanship Essay Contest "How do I model sportsmanship and how will it support my future success in today’s world? SECOND PLACE Eryn Flynn Ashland High School Sportsmanship and Success What constitutes a good player is not only talent, but sportsmanship as well. Players who embody sportsmanship play with integrity and have empathy for their opponents and teammates alike. I believe that I model these virtues and that they will lead to my future success by treating others with respect and handling adversity with poise. -

Sanctioned Cheer Teams - 2018-19 Activity SCHOOL Mailcity Coed Fall Cheer Abington High School Abington Acton-Boxborough Reg H.S

Sanctioned Cheer Teams - 2018-19 Activity SCHOOL MailCITY Coed Fall Cheer Abington High School Abington Acton-Boxborough Reg H.S. Acton Agawam High School Agawam Algonquin Reg. High School Northborough Amesbury High School Amesbury Andover High School Andover Apponequet Regional H.S. Lakeville Archbishop Williams High School Braintree Arlington High School Arlington Ashland High School Ashland Assabet Valley Reg Tech HS Marlboro Attleboro High School Attleboro Auburn High School Auburn Austin Preparatory School Reading Barnstable High School Hyannis Bartlett Jr./Sr. H.S. Webster Bay Path RVT High School Charlton Bedford High School Bedford Bellingham High School Bellingham Belmont High School Belmont Beverly High School Beverly Billerica Memorial High School Billerica Bishop Feehan High School Attleboro Blackstone-Millville Reg HS Blackstone Boston Latin School Boston Braintree High School Braintree Bridgewater-Raynham Reg High School Bridgewater Bristol-Plymouth Reg Voc Tech Taunton Brookline High School Brookline Burlington High School Burlington Canton High School Canton Carver Middle/High School Carver Central Catholic High School Lawrence Chelmsford High School North Chelmsford Chicopee Comprehensive HS Chicopee Clinton High School Clinton Cohasset Middle-High School Cohasset Concord-Carlisle High School Concord Tuesday, January 22, 2019 Sanctioned Cheer Teams - 2018-19 Activity SCHOOL MailCITY Coed Fall Cheer Coyle & Cassidy High School Taunton Danvers High School Danvers Dartmouth High School South Dartmouth David Prouty High School