B . A. Major Dissertation Presented for B.A. Degree

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MUNSTER VALES STRATEGIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN November 2020

Strategic Tourism Development Plan 2020-2025 Developing the TOURISM POTENTIAL of the Munster Vales munster vales 2 munster vales 3 Strategic Tourism Development Plan Strategic Tourism Development Plan CONTENTS Executive Summary Introduction 1 Destination Context 5 Consultation Summary 19 Case Studies 29 Economic Assessment 39 Strategic Issues Summary 49 Vision, Recommendations and Action Plan 55 Appendicies 85 Munster Vales acknowledge the funding received from Tipperary Local Community Development Committee and the EU under the Rural Development Programme 2014- 2020. “The European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development: Europe investing in rural areas.” Prepared by: munster vales 4 munster vales 5 Strategic Tourism Development Plan Strategic Tourism Development Plan MUNSTER VALES STRATEGIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN November 2020 Prepared by: KPMG Future Analytics and Lorraine Grainger Design by: KPMG Future Analytics munster vales i munster vales ii Strategic Tourism Development Plan Strategic Tourism Development Plan The context for this strategy is discussed in Part Two. To further raise the profile of Munster Vales, enhance the This includes an overview of progress which highlights the cohesiveness of the destination, and to maximise the opportunity following achievements since the launch of Munster Vales in presented by four local authorities working in partnership, this 2017: strategy was tasked with identifying a small number of ambitious products that could be developed and led by Munster Vales ■ Acted as an umbrella destination brand -

History and Explanation of the House Crests

History and Explanation of the House Crests In August 2014, the first team of House student leaders and House Deans created the original House crests. The crests reveal each House’s unique identity, and represent important aspects in the life of Blessed Edmund Rice, founder of the Christian Brothers. Members of the Edmund Rice Christian Brothers founded O’Dea High School in 1923. These crests help keep the charism of Blessed Edmund Rice alive at O’Dea. Edmund Rice founded some of the earliest Christian Brother Schools in County Dublin. By 1907, there were ten Christian Brother school communities throughout the county. Dublin’s crest’s cross is off centered like the shield of St. John. Blue represents the Virgin Mother and yellow represents Christ’s triumph over death on the cross. Dublin’s motto “Trean-Dilis” is Gaelic for “strength and faithfulness.” The dragon represents strength; the Gaelic knot represents brotherhood; the cross represents our faith and religious identity; and the hand over heart represents diversity. County Limerick was home to some of the earliest Christian Brother Schools, beginning in 1816. Limerick’s crest boasts five main symbols. The River Shannon runs through the center. The flame on the crest stands for excellence. The Irish knot symbolizes the brotherhood, exemplified by Limerick’s caring and supportive relationships. The Irish elk, a giant extinct deer, symbolizes both strength and courage. Limerick’s final symbol is a multicolored shamrock representing O’Dea’s four houses. Limerick’s motto is “Strength in Unity.” County Kilkenny is known as the birthplace of Edmund Rice. -

Waterford Industrial Archaeology Report

Pre-1923 Survey of the Industrial Archaeological Heritage of the County of Waterford Dublin Civic Trust April 2008 SURVEY OF PRE-1923 COUNTY WATERFORD INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE April 2008 CONTENTS 1. Introduction 1 2. Executive Summary 1 3. Methodology 3 4. Industrial Archaeology in Ireland 6 - Industrial Archaeology in Context 6 - Significance of Co. Waterford Survey 7 - Legal Status of Sites 9 5. Industrial Archaeology in Waterford 12 6. Description of Typologies & Significance 15 7. Issues in Promoting Regeneration 20 8. Conclusions & Future Research 27 Bibliography 30 Inventory List 33 Inventory of Industrial Archaeological Sites 36 Knockmahon Mines, Copper Coast, Co. Waterford SURVEY OF PRE-1923 COUNTY WATERFORD INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE 1. INTRODUCTION Waterford County Council, supported by the Heritage Council, commissioned Dublin Civic Trust in July 2007 to compile an inventory of the extant pre-1923 industrial heritage structures within Waterford County. This inventory excludes Waterford City from the perimeters of study, as it is not within the jurisdiction of Waterford County Council. This survey comes from a specific objective in the Waterford County Heritage Plan 2006 – 2011, Section 1.1.17 which requests “…a database (sic) the industrial and engineering heritage of County Waterford”. The aim of the report, as discussed with Waterford County Council, is not only to record an inventory of industrial archaeological heritage but to contextualise its significance. It was also anticipated that recommendations be made as to the future re-use of such heritage assets and any unexplored areas be highlighted. Mary Teehan buildings archaeologist, and Ronan Olwill conservation planner, for Dublin Civic Trust, Nicki Matthews conservation architect and Daniel Noonan consultant archaeologist were the project team. -

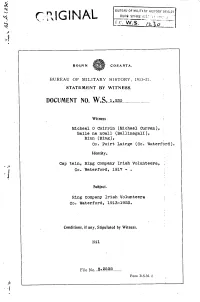

BMH.WS1230.Pdf

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 1,230 Witness Micheal 0 Cuirrin (Michael Curran), Baile na nGall (Ballinagall), Rinn (Ring), Co. Puirt Lairge (Co. Waterford). Identity. Cap tain, Ring Company Irish Volunteers, Co. Waterford, 1917 -. Subject. Ring Company Irish Volunteers Co. Waterford, 1913-1923. Conditions, if any, Stipulated byWitness Nil File No. S.2538 Form B.S.M.2 STATEMENTBY MÍCHEÁL Ó CUIRRÍN, Baile ma nGall, Rinn, Dún Garbháin, Co. Puirt Láirge. I was born in Bails na nGall, Ring, Co. Waterford, in the year 1897. My people were farmers, and native Irish speakers, as I am myself. My first connection with the National Movement was in 1913 when I joined the National Volunteers. We had a Company of about twenty-five men, and, when the split in the Volunteers occurred in 1915, every man of the twenty-five men left the National Volunteers and formed a Company of Irish Volunteers. We had at the time only a few guns, a couple of sporting rifles and a shot-gun or two. We got no advance news of the 1916 Rising and first heard about it when the Insurrection was actually 'on foot'. We got no orders to take any action in our district, and, consequently, took no part in the Rising at all. Following 1916, the Ring Company faded out for a while, but was reorganised in mid 1917 at which time I was in business at Wolfhill, Leix. When the Volunteers were reorganised in that area, the late P.J. -

An Phríomh-Oifig Staidrimh Central Statistics Office

An Phríomh-Oifig Staidrimh Central Statistics Office Published by the Stationery Office, Dublin, Ireland. To be purchased from the: Central Statistics Office, Information Section, Skehard Road, Cork. Government Publications Sales Office, Sun Alliance House, Molesworth Street, Dublin 2, or through any bookseller. Price €5.00 April 2012 © Government of Ireland 2012 Material compiled and presented by the Central Statistics Office. Reproduction is authorised, except for commercial purposes, provided the source is acknowledged. ISBN 978-1-4064-2653-3 Page Contents Foreword 5 Urbanisation across the country 7 We examine the urban/rural divide by county. Ireland’s towns 8 The growth of towns – both large and small. Population density 11 Looking at land area and population density for both urban and rural areas. Birthplace and residence 13 Looking at longer-term internal migration in the context of county of birth. Internal migration 18 People who moved in the year up to April 2011, their age, their destination and their home occupancy status. Statistical tables 26 Appendices 41 Profile 1 – Town and Country Foreword This report is the first of ten Profile reports examining in more detail the definitive results of Census 2011. This is a sister publication to the detailed tables published in Population Classified by Area. It examines topics such as the geographic distribution of the population, population density and internal migration - both longer term migration (in the context of county of birth) and more recent migration (i.e. those who moved in the year leading up to census night in April 2011). Other topics will be covered in further Profile reports to be released throughout 2012, and in two summary publications, This is Ireland – Highlights from Census 2011, Part 1 (published in March 2012) dealing with demographic factors, and This is Ireland – Highlights from Census 2011, Part 2 (due in June 2012) which will cover socio-economic themes. -

Dungarvan Leader 06 Jun 05.Pdf

MARIO'S MOTOR FACTORS MARY ST., DUNGARVAN hornibrooks Phone 058/42417 Lisrvioree • CAR PARTS • TRACTOR PARTS • TRUCK PARTS FOR mr and SOUTHERN DEMOCRAT NUMBER PLATES—15 mins. OIL FROM £6 GAL. Circulating throughout the County and City of Waterford, South Tipperary and South-East Cork TOYOTA \/„VolDungarvai . 49/IO . No. 2514OE-I/1 . FRIDAYrniriAv , JUN,, ... Er- c5 , 1987. nREGISTEREPOS T OFFICLeadeD E AATS THA ENEWSPAPE GENERALR nDPRIC,prE n25r p .(inc. rVAT) LISMORE HOSPITAL CLOSURE ———————^ .. -> Health Minister To Meet The Lismore District Hospital in Dublin on Monday last (May saga goes on with the an- 25) gave leave to a solicitor COULD BE MAJOR start to his tour with a planned nouncement last week-end that from Lismore to apply within the Minister for Health, Dr FINANCIAL BLOW FOR departure time of 11 p.m. He is 14 days ior a judicial review ol Rory O'Hanlon, had agreed to the Board's resolution of 7th HEALTH BOARD obviously anxious to meet as meet a deputation representing Deputation May, 1987 on the grounds that many local Fine Gael supporters the Lismore Save the Hospital the Board failed to comply with The decision of the President Committee on Thursday of this as possible and a Constituency outlay at th hospital could be Standing Orders and failed also of the District Court, District week to discuss the threatened e in Lismore the C.E.O.'s report to apply the principles of na- meeting has been arranged to closure of the hospital. The de- made in the current year. In- then states: "An exception has Justice Oliver J. -

27612 N9&N10 Waterford Makeup:TEMPALTE

27612 N9&N10 Waterford:TEMPALTE 12/6/08 17:42 Page 1 N9/N10 KILCULLEN TO WATERFORD SCHEME: N9/N10 KILCULLEN TO WATERFORD SCHEME: WATERFORD TO KNOCKTOPHER, WATERFORD TO KNOCKTOPHER, what we found background County Kilkenny County Kilkenny in brief: The N9/N10 Waterford to County Council. A total of 54 previously unknown Some of the findings from the scheme: sites dating from the fourth millennium BC to the 1 Knocktopher road project is 19th century AD were uncovered as a result of this work. Post-excavation analysis of the remains 1. Quern-stone the southernmost part of a discovered on these sites is ongoing. Quern-stone found within pit at Scart. (Photo: VJK Ltd) new national road linking Kilcullen to Carlow, This road is built through varied landscapes commencing with the valley of the River Suir in the Kilkenny and Waterford. south. It crosses over the Walsh Mountains between Mullinavat and Ballyhale and then descends into the 2 2. Cremation site The scheme involves the construction of 23.5 km of central lowlands of Kilkenny at Knocktopher. The dual carriageway between the Waterford City Bypass Cremated human bone on the floor of a cist at archaeological investigations have shown a greater and the town of Knocktopher, Co. Kilkenny. Knockmoylan. density and diversity of sites in lowland areas (Photo: VJK Ltd) compared with upland locations. These discoveries are Archaeological works were carried out by Margaret For more information Gowen & Co. Ltd and Valerie J Keeley Ltd (VJK Ltd) enabling archaeologists and historians to build upon between January 2006 and February 2007 on behalf the existing knowledge of man and the environment please contact: of the National Roads Authority and Kilkenny in this part of Ireland. -

Church Records Census Substitutes Newspapers Gravestone

Irish Roots 2016 Issue 4 on www.findmypast.ie which also and Waterford County Library. The Church Records hosts Griffith’s Valuation, commercial NLI’s sources database collection (http:// sources.nli.ie) is a goldmine of other Catholic baptism and marriage records directories, and other material. local material. It lists 175 rentals from for Waterford are relatively good in Waterford estates including the Boyle comparison to many Irish counties. Newspapers Estate rentals, (from 1691); Rentals of the There are 32 Catholic parishes (7 of The classic information associated Cavendish or Devonshire Estate (from which are within Waterford City) with newspapers are notices of births, 1812); and the Woulfe/Mansfield estate and 10 of these have records starting marriages and death. However, until papers (NLI Ms. 9632). An example of a in the 18th century (including all of relatively recent times these notices rental from the latter can be seen at www. the City parishes). The earliest register are restricted to the more prominent ancestornetwork.ie/small-sources-18. (St. John’s in Waterford City) starts in members of the community. However, 1710. The factors which affected the many others are mentioned because of start date of these records are detailed appearances in court or in local incidents. Local and Family Histories in ‘Irish Church Records’ (Flyleaf Press, Local newspapers also publish lists of Awareness of local history and culture 2001). The Catholic Church registers persons attending meetings, signing is helpful in revealing useful sources of are available online and free to access on petitions, or making donations to local information. -

Conserving Our Natural Heritage County Waterford Local Biodiversity

19786_WCC_Cover:WCC_BiodiversityCover 14/08/2008 12:45 Page 1 Waterford County Council, Comhairle Contae Phort Láirge, Civic Offices, Oifgí Cathartha, Dungarvan, Dún Garbhán, Conserving our Natural Heritage Co. Waterford. Co. Phort Láirge. Telephone: 058 22000 Guthán: 058 22000 County Waterford Local Biodiversity Action Plan Fax: 058 42911 Faics: 058 42911 www.waterfordcoco.ie Ag Sabháil ár nOidhreacht Nadúrtha Plean Bithéagsúlachta Chontae Phort Láirge ISBN 978-0-9532022-6-3 2008 - 2013 19786_WCC_Cover:WCC_BiodiversityCover 14/08/2008 12:45 Page 2 Acknowledgements Waterford County Council wishes to acknowledge the generous support of the Heritage Council in the preparation of the plan and also for provision of funding for the implementation of the Biodiversity Action Plan in 2008. Publication compiled by Mieke Mullyaert and Dominic Berridge (former Heritage Officer) and edited by Bernadette Guest, Heritage Officer Use of images kindly permitted by Andrew Kelly, Mike Trewby, Brian White, Dr. Liam Lysaght, Dr. Peter Turner, Dr. Shelia Donegan, Dominic Berridge, Andrew Byrne, Catherine Keena, and Will Woodrow. Publication designed and produced by Intacta Print Ltd . For further information on the Waterford Biodiversity Plan and Biodiversity projects contact the heritage officer at [email protected] or www.waterfordcoco.ie/heritage Cover photographs: Pair of Chough, Pine Marten (Andrew Kelly) Red Squirrel (Brian White), Coastal earth bank (Mike Trewby) Back cover photograph: Panorama of Dungarvan Bay (Bernadette Guest) 19786_WCCBio_Bro:WCC 14/08/2008 12:42 Page 1 Contents A vision for biodiversity in County Waterford 4 1. Introduction 5 The landscape of County Waterford 5 What is biodiversity? 5 Why is biodiversity important? 5 Why a biodiversity action plan? 6 The process by which the plan was developed 7 Plan structure 7 Who is the plan for? 7 2. -

Lismore Castle Papers Descriptive List Waterford County Archives

Lismore Castle Papers LISMORE CASTLE PAPERS DESCRIPTIVE LIST WATERFORD COUNTY ARCHIVES IE/WCA/PP/LISM 1 Lismore Castle Papers Repository Repository Name: Waterford County Archives Identity Statement Reference Code: IE WCA PP LISM Titles: Lismore Castle Estate Papers Dates: [1750]-31 December 1969 Level of Description: Fonds Extent: 208 boxes Creator Creators: Lismore Estate, Irish Estates of the Dukes of Devonshire Administrative History: Lismore Castle was the seat of the Dukes of Devonshire in Ireland. William, the 4th Duke of Devonshire (1720-1764) married Lady Charlotte Boyle (1731-1754), heiress of the 3rd Earl of Burlington and through this marriage the Irish estate mainly situated in counties Waterford and Cork became part of the estates of the Dukes of Devonshire. The Irish estates were administered from Lismore Castle, Lismore, County Waterford by agents living and working from Lismore Castle and responsible for all the Irish estates of the Dukes of Devonshire with a sub-agent located in Bandon to administer the lands and properties located in the areas surrounding Bandon in county Cork. The seat of the Dukes of Devonshire is Chatsworth in Derbyshire, England. The Dukes visited Lismore on occasion, in particular, to hunt and fish but were not permanent residents of Lismore Castle. Instead, the estate was administered by agents who were closely supervised by the Dukes of Devonshire through a series of detailed and, in some cases, daily, correspondence. During the period covered by these papers there were a number of holders of the title of Duke of Devonshire who held the Lismore estates. William Cavendish, 5th Duke of Devonshire (1748-1811) who married Lady Georgiana Spencer; William Spencer Cavendish, the 6th Duke (1790-1858), 2 Lismore Castle Papers known as the “Bachelor Duke”, who extensively remodeled Lismore Castle. -

WATERFORD Service Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Town County Registered Provider Telephone Number Service Type Conditions of Service Attached

Early Years Services WATERFORD Service Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Town County Registered Provider Telephone Number Service Type Conditions of Service Attached Stepping Stones Pre-School Main Street Ardmore Waterford Jane O'Sullivan 087 6221560 Sessional Butterflies Community St. Michael’s Hall Ballyduff Upper Waterford Claire Nicolls 058 60390 Sessional Playgroup Ballymacarbry Ballymacarbry Montessori Ballymacarbry Waterford Clodagh Burke 086 1081784 Sessional Community Centre Regulation 23 - Safeguarding Fr Rufus Halley Butlerstown Playschool Old National School Butlerstown Waterford Denise Doherty 051 373560 Part Time Health, Centre Safety and Welfare of Child Little Einsteins Pre-school Kilronan Butlerstown Waterford Susan Molloy 051 399953 Sessional Cappoquin Community Twig Bog Cappoquin Waterford Orla Nicholson 058 52746 Full Day Childcare Facility Shirley's Childcare The Crossroads Russian Side Cheekpoint Waterford Shirley Ferguson 089 4781113 Sessional Coill Mhic Naíonra Choill Mhic Thomáisín Graigseoinín Waterford Maire Uí Chéitinn 051 294818 Sessional Thomáísín Naionra Na Rinne Halla Pobail Maoil a' Chóirne An Rinn Dún Garbhán Waterford Breege Uí Mhurchadha 058 46933 Sessional Naionra Na Tsean Phobail Lios na Síog An Sean Phobal Dún Garbhán Waterford Joanne Ní Mhuiríosa 058 46622 Sessional Ballinroad Pre-School St. Laurence's Hall Ballinroad Dungarvan Waterford Patricia Collins 087 1234004 Sessional Bright Stars Clonea Clonea Stand Hotel Clonea Dungarvan Waterford Yvonne Kelly Part Time Regulation Brightstars Cruachan -

Waterford Archaeologi & Historical Society

WATERFORD ARCHAEOLOGI & HISTORICAL SOCIETY No. 55 1999 Irisleabhar Cumann Seandiilaiochta agus Staire Phort Liiirge I BARDAS PHORT LAIRGE WATERFORD CORPORATION The WarcrSord Archaeological md Historical Society and thc ctlitor of DECIES gratefully acknowlcdgc thc gencrous sponsorship of Watcrl.orc1 Corporation low~u-clsthc publication costs of thi\ joi11m1. Ilecirs 55, 1990 ISSN 1393-3 1 16 Publishcd by Thc Waterford Archacolog~c~aland Historical Socicry Psintccl by Lcinster Leader Ltd. Nx~s.Co. Kildarc. I Decies 55 Decies 55 CONTENTS PAGE Message from the Chairman ........ v ... List of Contributors ............................ \'I11 Medieval Undercrofts EIucidated: 0.Scully ............................... ................................ Waterford men irt the Inwlides, paris, 1690- 177 1: E 6 Hannrachdin ............................................................................... As others saw us: a French visitor's impression of Waterford in 1784: B. Payet & D. 6 Ceallachdin ............................................................ Some aspecls of Lemuel Cox's bridge: P. Grogan ...................................................................................................................... 27 From County Waterford to Australia in 1823: John Uniacke's personal chronicle of migra- tion and exploration: S. RiviPw .......................................... Mount Melleray Seminary: Fr U. d Maidin ............................................................................. List of County Waterford Soldiers who died in Wol Id War