The Search for Talent by Lee Kuan Yew, Prime Minister

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interview NTD Full Transcript.Pdf

INTERVIEW Mr Ngiam Tong Dow Singapore – International Medical Centre: A Missed Opportunity, or Not Too Late? By Dr Toh Han Chong, Editor The Singapore healthcare sector has been in flux and yet also in transformation. While well regarded internationally to be robust and reputable, it will continue to face imminent challenges. The speaker for this year’s SMA Lecture, Mr Ngiam Tong Dow, taps on his deep and wide experience in various ministries to offer insights and wisdom on many issues: Singapore as an international medical centre, the possibility of supplier-induced demand in healthcare, as well as his political vision and opinion on Hainanese chicken rice. This is the full version of the SMA News interview with Mr Ngiam. The contents of this interview are not to be printed in whole or in part without prior approval of the Editor (email [email protected]). (For the version published in our September 2013 issue, please see http://goo.gl/DDAcyd.) SMA Lecture 2013 Dr Toh Han Chong – THC: The upcoming SMA Lecture is titled Developing Singapore as an International Medical Centre. Why did you choose this topic? Mr Ngiam Tong Dow – NTD: In Economics, there are two types of economies – production-based and knowledge-based. The former depends on land, labour and capital, but it is the latter that Singapore really needed. This was clear to me as Chairman of Economic Development Board (EDB) in the 1980s. We could not offer cheap labour and cheap land for long. We needed to have a significant niche. At that time, we identified two key areas. -

The Enduring Ideas of Lee Kuan Yew

THE STRAITS TIMES By Invitation The enduring ideas of Lee Kuan Yew Kishore Mahbubani (mailto:[email protected]) PUBLISHED MAR 12, 2016, 5:00 AM SGT Integrity, institutions and independence - these are three ideas the writer hopes will endure for Singapore. March 23 will mark the first anniversary of the passing of Mr Lee Kuan Yew. On that day, the National University of Singapore (NUS) and the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy will be organising a forum, The Enduring Ideas of Lee Kuan Yew. The provost of NUS, Professor Tan Eng Chye, will open the forum. The four distinguished panellists will be Ambassador-at-Large Chan Heng Chee, Foreign Secretary of India S. Jaishankar, Dr Shashi Jayakumar and Mr Zainul Abidin Rasheed. This forum will undoubtedly produce a long list of enduring ideas, although only time will tell which ideas will really endure. History is unpredictable. It does not move in a straight line. Towards the end of their terms, leaders such as Mr Jawaharlal Nehru, Mr Ronald Reagan and Mrs Margaret Thatcher were heavily criticised. Yet, all three are acknowledged today to be among the great leaders of the 20th century. It is always difficult to anticipate the judgment of history. ST ILLUSTRATION : MIEL If I were to hazard a guess, I would suggest that three big ideas of Mr Lee that will stand the test of time are integrity, institutions and the independence of Singapore. I believe that these three ideas have been hardwired into the Singapore body politic and will last. INTEGRITY The culture of honesty and integrity that Mr Lee and his fellow founding fathers created is truly a major gift to Singapore. -

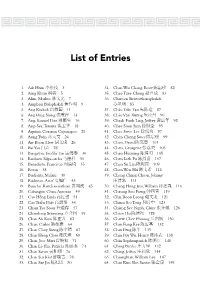

List of Entries

List of Entries 1. Aik Htun 3 34. Chan Wai Chang, Rose 82 2. Aing Khun 5 35. Chao Tzee Cheng 83 3. Alim, Markus 7 36. Charoen Siriwatthanaphakdi 4. Amphon Bulaphakdi 9 85 5. Ang Kiukok 11 37. Châu Traàn Taïo 87 6. Ang Peng Siong 14 38. Châu Vaên Xöông 90 7. Ang, Samuel Dee 16 39. Cheah Fook Ling, Jeffrey 92 8. Ang-See, Teresita 18 40. Chee Soon Juan 95 9. Aquino, Corazon Cojuangco 21 41. Chee Swee Lee 97 10. Aung Twin 24 42. Chen Chong Swee 99 11. Aw Boon Haw 26 43. Chen, David 101 12. Bai Yao 28 44. Chen, Georgette 103 13. Bangayan, Teofilo Tan 30 45. Chen Huiming 105 14. Banharn Silpa-archa 33 46. Chen Lieh Fu 107 15. Benedicto, Francisco 35 47. Chen Su Lan 109 16. Botan 38 48. Chen Wen Hsi 111 17. Budianta, Melani 40 49. Cheng Ching Chuan, Johnny 18. Budiman, Arief 43 113 19. Bunchu Rotchanasathian 45 50. Cheng Heng Jem, William 116 20. Cabangon Chua, Antonio 49 51. Cheong Soo Pieng 119 21. Cao Hoàng Laõnh 51 52. Chia Boon Leong 121 22. Cao Trieàu Phát 54 53. Chiam See Tong 123 23. Cham Tao Soon 57 54. Chiang See Ngoh, Claire 126 24. Chamlong Srimuang 59 55. Chien Ho 128 25. Chan Ah Kow 62 56. Chiew Chee Phoong 130 26. Chan, Carlos 64 57. Chin Fung Kee 132 27. Chan Choy Siong 67 58. Chin Peng 135 28. Chan Heng Chee 69 59. Chin Poy Wu, Henry 138 29. Chan, Jose Mari 71 60. -

Induction Comitia & Gordon Arthur Ransome Oration Programme Book

INDUCTION COMITIA 2013 & 21ST21ST GORDON GORDON ARTHUR ARTHUR RANSOME RANSOME ORATION ORATION 1 INDUCTION COMITIA 2013 & 21ST GORDON ARTHUR RANSOME ORATION Master of Ceremonies: Dr Sophia Ang College of Anaesthesiologists, Singapore PROGRAMME 5:50 pm Guests to be seated 6:00 pm Arrival of Guest-of-Honour, His Excellency Dr Tony Tan Keng Yam President of the Republic of Singapore Patron, Academy of Medicine, Singapore 6:15 pm Procession of Stage Party 6:20 pm Addresses Dr Lim Shih Hui Master, Academy of Medicine, Singapore Dr Chang Keng Wee Master, Academy of Medicine of Malaysia Dr Donald K T Li President, Hong Kong Academy of Medicine 6:30 pm Conferment of Honorary Fellowship on Mr Tharman Shanmugaratnam Deputy Prime Minister & Minister for Finance, Republic of Singapore 21st Gordon Arthur Ransome Orator 6:40 pm Conferment of Fellowships • Presidents of Overseas Colleges • New Fellows, Academy of Medicine, Singapore 7:10 pm Inductees’ Pledge Chief Inductee: Dr Alex Sia College of Anaesthesiologists, Singapore 7:15 pm Presentation of Certifi cates for Staff Registrar Scheme Diplomas 7:20 pm 21st Gordon Arthur Ransome Oration by Mr Tharman Shanmugaratnam “A Fair and Just Society: What Stays, What Changes?” 8:00 pm Dinner Reception 9:00 pm End of Programme INDUCTION COMITIA 2013 & 2 21ST GORDON ARTHUR RANSOME ORATION Guest-Of-Honour GUEST-OF-HONOUR His Excellency DR TONY TAN KENG YAM President of the Republic of Singapore and Patron of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore INDUCTION COMITIA 2013 & 21ST GORDON ARTHUR RANSOME ORATION 1 Master, -

I N T H E S P I R I T O F S E R V I

The Old Frees’ AssOCIatION, SINGAPORE Registered 1962 Live Free IN THE SPIRIT OF SERVING Penang Free School 1816-2016 Penang Free School in August 2015. The Old Frees’ AssOCIatION, SINGAPORE Registered 1962 www.ofa.sg Live Free IN THE SPIRIT OF SERVING AUTHOR Tan Chung Lee PUBLISHER The Old Frees’ Association, Singapore PUBLISHER The Old Frees’ Association, Singapore 3 Mount Elizabeth #11-07, Mount Elizabeth Medical Centre Singapore 228510 AUTHOR Tan Chung Lee OFAS COFFEE-TABLE BOOK ADJUDICATION PANEL John Lim Kok Min (co-chairman) Tan Yew Oo (co-chairman) Kok Weng On Lee Eng Hin Lee Seng Teik Malcolm Tan Ban Hoe OFAS COFFEE-TABLE BOOK WORKGROUP Alex KH Ooi Cheah Hock Leong The OFAS Management Committee would like to thank Gabriel Teh Choo Thok Editorial Consultant: Tan Chung Lee the family of the late Chan U Seek and OFA Life Members Graphic Design: ST Leng Production: Inkworks Media & Communications for their donations towards the publication of this book. Printer: The Phoenix Press Sdn Bhd 6, Lebuh Gereja, 10200 Penang, Malaysia The committee would also like to acknowledge all others who PHOTOGRAPH COPYRIGHT have contributed to and assisted in the production of this Penang Free School Archives Lee Huat Hin aka Haha Lee, Chapter 8 book; it apologises if it has inadvertently omitted anyone. Supreme Court of Singapore (Judiciary) Family of Dr Wu Lien-Teh, Chapter 7 Tan Chung Lee Copyright © 2016 The Old Frees’ Association, Singapore All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be produced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of The Old Frees’ Association, Singapore. -

60 Years of National Development in Singapore

1 GROUND BREAKING 60 Years of National Development in Singapore PROJECT LEADS RESEARCH & EDITING DESIGN Acknowledgements Joanna Tan Alvin Pang Sylvia Sin David Ee Stewart Tan PRINTING This book incorporates contributions Amit Prakash ADVISERS Dominie Press Alvin Chua from MND Family agencies, including: Khoo Teng Chye Pearlwin Koh Lee Kwong Weng Ling Shuyi Michael Koh Nicholas Oh Board of Architects Ong Jie Hui Raynold Toh Building and Construction Authority Michelle Zhu Council for Estate Agencies Housing & Development Board National Parks Board For enquiries, please contact: Professional Engineers Board The Centre for Liveable Cities Urban Redevelopment Authority T +65 6645 9560 E [email protected] Printed on Innotech, an FSC® paper made from 100% virgin pulp. First published in 2019 © 2019 Ministry of National Development Singapore All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Every effort has been made to trace all sources and copyright holders of news articles, figures and information in this book before publication. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, MND will ensure that full credit is given at the earliest opportunity. ISBN 978-981-14-3208-8 (print) ISBN 978-981-14-3209-5 (e-version) Cover image View from the rooftop of the Ministry of National Development building, illustrating various stages in Singapore’s urban development: conserved traditional shophouses (foreground), HDB blocks at Tanjong Pagar Plaza (centre), modern-day public housing development Pinnacle@Duxton (centre back), and commercial buildings (left). -

PRESS RELEASE Media Division, Ministry of Information & the Arts, 36Th Storey

Singapore Government PRESS RELEASE Media Division, Ministry of Information & The Arts, 36th Storey. PSA Building, 460 Alexandra Road, Singapore 0511. Tel 2799794/5 Embargoed Until After Delivery Please Check Against Delivery SPEECH BY PRIME MINISTER IN PARLIAMENT ON TUESDAY. 18 JAN 94 Review of 1993 I look back on 1993 with some satisfaction. Our economy grew strongly. It was the best performance since 1988. 2 We also put in place policies which will sustain our robust growth - going regional, tax reform through the GST, autonomous schools, health care reform, and raising retirement age to 60. 3 We introduced practical schemes to increase Singaporeans' assets - upgrading HDB flats, selling HDB shops to create a new class of commercial property owners, the CPF Share Top-up Scheme, selling Singapore Telecom Group 'A' shares to make Singapore a nation of share-owners. 4 The upgrading of HDB flats and sale of HDB shops are one-off programmes: the recipients benefit only once, although the programmes will be stretched out over a number of years. In contrast, the CPF Share Top-up Scheme and the sale of shares of privatised statutory boards will benefit Singaporeans each time the economy does exceptionally well, and each time we privatise another statutory board. 5 We will periodically top-up Singaporeans' CPF accounts, provided we enjoy good growth and exceptional budget surplus. This will achieve two objectives: one, increase the assets of Singaporeans, and two, bring home the message that our individual prosperity is linked to the collective prosperity of the nation. If all of us work together to increase the wealth of the country, a portion of it will be redistributed to the people in the form of CPF Top-up or shares sold at a discount. -

World Bank Document

PW -ZM/fl.\-. ' ' ttl'lF. U Y Q I A tt?blsD1^ ffR E ST R IC TE D Report No. DB-55a Public Disclosure Authorized This report was prepared for use within the Bank and its affiliated organizations. They do not accept responsibHftv fnr its ntrorvn r rnmnpltenes The report may not be published nor may it be quoted as representing their views. TMTVPMATT(hNAT&L BANK PC)R RECONSTRUCITION AND DTlVP.T.CPMVNT INTPRNATTCONAT DEVELOPMENT ASSOCTATION Public Disclosure Authorized APPRAISAL OF DEVELOPMENT BANKC OF SINGAPORE LTD. Public Disclosure Authorized December 29, 1969 Public Disclosure Authorized Development Finance Companies Department Currency Equivalents 3$ 1 US$ C).327 US$ 1 ,S$ 3.06 S$ 1 million = US$327,000 APPRAISAL OF DEVELOPMENT BANK OF SINGAPORE LTD. CONTENTS Page Paragrc+h SUTPINARY i - ii i - vi.i I. 2ITRODUCTION 1 - 2 1 - 2 II. ENVEIRONMENT 1 - 5 3 - 21 Recent Economic Growth 2 4 Industrial Expansion 2 - 5 - 8 Industrial Finance 2 - 9 9 - 21 III. ESTABLISHIDENT OF DBS 5 - 9 22 - 38 Formation 5 22 - 24 Scope of Operations 5 - 6 25 - 26 Ownership 6 - 7 27 - 30 Board of. Directors 7 31 Executive Committee 7 - 8 32 - 33 MlaInagement and Staff .8 - , 3) = 3 vT. RESOURCES ldrID PFOOR`TFOLIO -l 1 1 39l GP Resources 9 - 39 - 4 Loan Portfolio taken over from 7B 10 - 11 42 - 46 Undisbursed EDB Commitments 11 47 EDBis Equity Portfolio 11 48 V. POLICIES AhD PROCEDuRES 12 - i4 49 - 58 Policies 12 - 13 49 53 Procedures 13 - 1 5 - 58 VI. DBS'S OPERATIONS l - 18 59 - 67 Summary of Operations 14 59 - 60 Long-term Lending Operations 15 - 16 61 Light lndustries Loans 16 62 Equity Investments 17 63 Conmercial Banlcing Operations 17 6L Guarantees 17 65 Underwriting Activities 17 66 Real Estate Operations 17 - 18 67 Page Paragraph VII. -

Anti-Corruption Agencies in Four Asian Countries: a Comparative Analysis*

ANTI-CORRUPTION AGENCIES IN FOUR ASIAN COUNTRIES: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS Jon S.T. Quah ABSTRACT To be effective, anti-corruption agencies (ACAs) must satisfy these six preconditions: (1) they must be incorruptible; (2) they must be independent from the police and from political control; (3) there must be comprehensive anti-corruption legislation; (4) they must be adequately staffed and funded; (5) they must enforce the anti-corruption laws impartially; and (6) their governments must be committed to curbing corruption in their countries. This article assesses the effectiveness of the ACAs in Singapore, Hong Kong, Thailand and South Korea in terms of these preconditions. It concludes that the ACAs in Hong Kong and Singapore are more effective than their counterparts in South Korea and Thailand because of the political will of their governments, which is reflected in the provision of adequate staff and budget to Hong Kong’s Independent Commission Against Corruption and Singapore’s Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau, and the impartial enforcement of the comprehensive anti-corruption laws in both city-states. INTRODUCTION Corruption is a serious problem in many Asian countries, judging from their ranking and scores on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI). To combat corruption these countries have relied on three patterns of corruption control. The first pattern relies on the enactment of anti-corruption laws without a specific agency to enforce these laws. For example in Mongolia, the Law on Anti-Corruption that was introduced in April 1996 is jointly implemented by the police, the General Prosecutor’s Office, and the Courts (Quah, 2003a, p. -

PRIME MINISTER's TRIBUTE to the LATE PRESIDENT, DR BENJAMIN HENRY SHEARES, in PARLIAMENT on 12 JUNE 1981 Mr Deputy Speaker

1 PRIME MINISTER’S TRIBUTE TO THE LATE PRESIDENT, DR BENJAMIN HENRY SHEARES, IN PARLIAMENT ON 12 JUNE 1981 Mr Deputy Speaker, I rise to speak in memory of the late President Dr Benjamin Henry Sheares. He was born on 12 August 1907 in Singapore, the son of a former Public Works Department technical supervisor. He was educated at the Methodist Girls’ School, Raffles Institution and the King Edward VII College of Medicine. I first knew him 41 years ago in 1940 when he moved into a house diagonally opposite where I was living in Norfolk Road. He was a rising gynaecologist at Kandang Kerbau Hospital. He had won a Queen’s Fellowship for two years post-graduate study in Britain. He could not go because of the outbreak of World War II. During the Japanese occupation, he was to become Head of the Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology at Kandang Kerbau Hospital and Medical Superintendent of a hospital for the local patients section, in other words in charge of all other than Japanese patients. lky/1981/lky0612.doc 2 I moved from Norfolk Road in 1944. In those 3 ½ years we lived opposite each other, we were not close friends. I was 15 years his junior; but we knew each other. At the end of 1970, when our first President, Yusof Ishak, died, the Cabinet considered several persons for a successor. Dr Benjamin Sheares was the most eminent. He was so obviously a suitable choice. The Cabinet agreed that I approached him. He was surprised, delighted, and, at the same time, apprehensive. -

From Colonial Segregation to Postcolonial ‘Integration’ – Constructing Ethnic Difference Through Singapore’S Little India and the Singapore ‘Indian’

FROM COLONIAL SEGREGATION TO POSTCOLONIAL ‘INTEGRATION’ – CONSTRUCTING ETHNIC DIFFERENCE THROUGH SINGAPORE’S LITTLE INDIA AND THE SINGAPORE ‘INDIAN’ ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy IN THE UNIVERSITY OF CANTERBURY BY SUBRAMANIAM AIYER UNIVERSITY OF CANTERBURY 2006 ---------- Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION 3 Thesis Argument 3 Research Methodology and Fieldwork Experiences 6 Theoretical Perspectives 16 Social Production of Space and Social Construction of Space 16 Hegemony 18 Thesis Structure 30 PART I - SEGREGATION, ‘RACE’ AND THE COLONIAL CITY Chapter 1 COLONIAL ORIGINS TO NATION STATE – A PREVIEW 34 1.1 Singapore – The Colonial City 34 1.1.1 History and Politics 34 1.1.2 Society 38 1.1.3 Urban Political Economy 39 1.2 Singapore – The Nation State 44 1.3 Conclusion 47 2 INDIAN MIGRATION 49 2.1 Indian migration to the British colonies, including Southeast Asia 49 2.2 Indian Migration to Singapore 51 2.3 Gathering Grounds of Early Indian Migrants in Singapore 59 2.4 The Ethnic Signification of Little India 63 2.5 Conclusion 65 3 THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE COLONIAL NARRATIVE IN SINGAPORE – AN IDEOLOGY OF RACIAL ZONING AND SEGREGATION 67 3.1 The Construction of the Colonial Narrative in Singapore 67 3.2 Racial Zoning and Segregation 71 3.3 Street Naming 79 3.4 Urban built forms 84 3.5 Conclusion 85 PART II - ‘INTEGRATION’, ‘RACE’ AND ETHNICITY IN THE NATION STATE Chapter -

Lee Kuan Yew Continue to flow As Life Returns to Normal at a Market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, Three Days After the State Funeral Service

TODAYONLINE.COM WE SET YOU THINKING SUNDAY, 5 APRIL 2015 SPECIAL EDITION MCI (P) 088/09/2014 The tributes to the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew continue to flow as life returns to normal at a market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, three days after the State Funeral Service. PHOTO: WEE TECK HIAN REMEMBERING MR LEE KUAN YEW SPECIAL ISSUE 2 REMEMBERING LEE KUAN YEW Tribute cards for the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew by the PCF Sparkletots Preschool (Bukit Gombak Branch) teachers and students displayed at the Chua Chu Kang tribute centre. PHOTO: KOH MUI FONG COMMENTARY Where does Singapore go from here? died a few hours earlier, he said: “I am for some, more bearable. Servicemen the funeral of a loved one can tell you, CARL SKADIAN grieved beyond words at the passing of and other volunteers went about their the hardest part comes next, when the DEPUTY EDITOR Mr Lee Kuan Yew. I know that we all duties quietly, eiciently, even as oi- frenzy of activity that has kept the mind feel the same way.” cials worked to revise plans that had busy is over. I think the Prime Minister expected to be adjusted after their irst contact Alone, without the necessary and his past week, things have been, many Singaporeans to mourn the loss, with a grieving nation. fortifying distractions of a period of T how shall we say … diferent but even he must have been surprised Last Sunday, about 100,000 people mourning in the company of others, in Singapore. by just how many did.