Chapter 5 Safety

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rural Expressway Intersection Synthesis of Practice and Crash Analysis

RURAL EXPRESSWAY INTERSECTION SYNTHESIS OF PRACTICE AND CRASH ANALYSIS Sponsored by the Iowa Department of Transportation (CTRE Project 03-157) Final Report October 2004 Disclaimer Notice The opinions, fi ndings, and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Iowa Department of Transportation. The sponsor(s) assume no liability for the contents or use of the information contained in this document. This report does not constitute a standard, specifi cation, or regulation. The sponsor(s) do not endorse products or manufacturers. About CTRE/ISU The mission of the Center for Transportation Research and Education (CTRE) at Iowa State Uni- versity is to develop and implement innovative methods, materials, and technologies for improv- ing transportation effi ciency, safety, and reliability while improving the learning environment of students, faculty, and staff in transportation-related fi elds. Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. CTRE Project 03-157 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Rural Expressway Intersection Synthesis of Practice and Crash Analysis October 2004 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. T. H. Maze, Neal R. Hawkins, and Garrett Burchett 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Center for Transportation Research and Education Iowa State University 11. Contract or Grant No. 2901 South Loop Drive, Suite 3100 Ames, IA 50010-8634 12. Sponsoring Organization Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Iowa Department of Transportation Final Report 800 Lincoln Way 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Ames, IA 50010 15. -

What Are the Advantages of Roundabouts?

What is a roundabout? A roundabout is an intersection where traffic travels around a Circulatory central island in a counter- Truck Apron Roadway clockwise direction. Vehicles entering or exiting the roundabout must yield to vehicles, bicyclists, and pedestrians. Figure 1 presents the elements of a roundabout. Yield Line Splitter Island Figure 1: Elements of a Roundabout What are the advantages of roundabouts? • Less Traffic Conflict: Figure 2 compares the conflict points between a conventional intersection and a modern roundabout. The lower number of conflict points translates to less potential for accidents. • Greater safety(1): Primarily achieved by slower speeds and elimination of left turns. Design elements of the roundabouts cause drivers to reduce their speeds. • Efficient traffic flow: Up to 50% increase in traffic capacity • Reduced Pollution and fuel usage: Less stops, shorter queues and no left turn storage. • Money saved: No signal equipment to install or maintain, plus savings in electricity use. • Community benefits: Traffic calming and enhanced aesthetics by landscaping. (1) Statistics published by the U.S. Dept. of transportation, Federal Highway Administration shows roundabouts to have the following advantages over conventional intersections: • 90% reduction in fatalities • 76% reduction in injuries • 35% reduction in pedestrian accidents. Signalized Intersection Roundabout Figure 2: Conflict Point Comparison How to Use a Roundabout Driving a car • Slow down as you approach the intersection. • Yield to pedestrians and bicyclists crossing the roadway. • Watch for signs and pavement markings. • Enter the roundabout if gap in traffic is sufficient. • Drive in a counter-clockwise direction around the roundabout until you reach your exit. Do not stop or pass other vehicles. -

Movingforward

FORWARD movingfAll 2010 A quarterly review of news and information about Pennsylvania local roads. When to Use Stop Signs in Alleys A Guide to Understanding the State’s Requirements Related to Traffic-Control Devices at Alley Intersections by Patrick Wright, Pennoni Associates When deciding whether to use stop signs and other An alley is considered a “highway” in the Vehicle traffic-control devices in alleys, municipalities Code because it is a “roadway open to the use of the should be familiar with two major issues. The first public.” Following this logic, the junction of an alley is whether traffic control is even required, and the with another highway (including another alley) is con- second is how to properly place the signs especially sidered an “intersection” under the Vehicle Code, and within the space constraints found in most alleys. thus crosswalks (whether marked or unmarked) exist. Understanding Alleys What Traffic-Control and Intersections Devices Are Required? Alleys are defined separately in both the Now that the definitions of alleys and intersec- Pennsylvania Vehicle Code (Title 75) and the tions have been clarified, the next step is to deter- Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices mine what traffic-control devices are required for (MUTCD). According to the Vehicle Code (Title alleys. As at any intersection, the Vehicle Code does 75, Section 102) as well as the MUTCD, an alley not necessarily require stop signs or other traffic-con- is “a street or highway intended to provide access to trol devices. Instead, the code has specific “rules of the rear or side of lots or buildings in urban districts the road” that govern driving behavior and the right- and not intended for the purpose of through of-way at intersections depending on the situation. -

Arlington County Pavement Marking Specifications

DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES ARLINGTON COUNTY PAVEMENT MARKING SPECIFICATIONS MAY 2017 T-1.1 PAVEMENT MARKINGS Table of Contents 1. General ................................................................................................................................................ 2 2. Design Criteria ...................................................................................................................................... 3 3. Marking Plan Preparation ..................................................................................................................... 4 Exhibits ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 MK – 1 Typical Crosswalk ......................................................................................................................... 5 MK – 1a Typical Crosswalk Details .............................................................................................................. 6 MK – 2 Typical Cross Section ..................................................................................................................... 7 MK – 3 Typical Speed Hump Markings ...................................................................................................... 8 MK – 4 Typical Speed Table ...................................................................................................................... 9 MK – 4a Typical Speed Hump Details ....................................................................................................... -

Access Control

Access Control Appendix D US 54 /400 Study Area Proposed Access Management Code City of Andover, KS D1 Table of Contents Section 1: Purpose D3 Section 2: Applicability D4 Section 3: Conformance with Plans, Regulations, and Statutes D5 Section 4: Conflicts and Revisions D5 Section 5: Functional Classification for Access Management D5 Section 6: Access Control Recommendations D8 Section 7: Medians D12 Section 8: Street and Connection Spacing Requirements D13 Section 9: Auxiliary Lanes D14 Section 10: Land Development Access Guidelines D16 Section 11: Circulation and Unified Access D17 Section 12: Driveway Connection Geometry D18 Section 13: Outparcels and Shopping Center Access D22 Section 14: Redevelopment Application D23 Section 15: Traffic Impact Study Requirements D23 Section 16: Review / Exceptions Process D29 Section 17: Glossary D31 D2 Section 1: Purpose The Transportation Research Board Access Management Manual 2003 defines access management as “the systematic control of the location, spacing, design, and operations of driveways, median opening, interchanges, and street connections to a roadway.” Along the US 54/US-400 Corridor, access management techniques are recommended to plan for appropriate access located along future roadways and undeveloped areas. When properly executed, good access management techniques help preserve transportation systems by reducing the number of access points in developed or undeveloped areas while still providing “reasonable access”. Common access related issues which could degrade the street system are: • Driveways or side streets in close proximity to major intersections • Driveways or side streets spaced too close together • Lack of left-turn lanes to store turning vehicles • Deceleration of turning traffic in through lanes • Traffic signals too close together Why Access Management Is Important Access management balances traffic safety and efficiency with reasonable property access. -

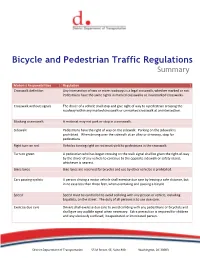

DC Bicycle and Pedestrian Traffic Regulations Summary

Bicycle and Pedestrian Traffic Regulations Summary Motorist Responsibilities Regulation Crosswalk definition Any intersection of two or more roadways is a legal crosswalk, whether marked or not. Pedestrians have the same rights in marked crosswalks as in unmarked crosswalks. Crosswalk without signals The driver of a vehicle shall stop and give right of way to a pedestrian crossing the roadway within any marked crosswalk or unmarked crosswalk at an intersection. Blocking a crosswalk A motorist may not park or stop in a crosswalk. Sidewalk Pedestrians have the right of way on the sidewalk. Parking on the sidewalk is prohibited. When driving over the sidewalk at an alley or driveway, stop for pedestrians. Right turn on red Vehicles turning right on red must yield to pedestrians in the crosswalk Turn on green A pedestrian who has begun crossing on the walk signal shall be given the right-of-way by the driver of any vehicle to continue to the opposite sidewalk or safety island, whichever is nearest. Bikes lanes Bike lanes are reserved for bicycles and use by other vehicles is prohibited. Cars passing cyclists A person driving a motor vehicle shall exercise due care by leaving a safe distance, but in no case less than three feet, when overtaking and passing a bicycle Speed Speed must be controlled to avoid colliding with any person or vehicle, including bicyclists, on the street. The duty of all persons is to use due care. Exercise due care Drivers shall exercise due care to avoid colliding with any pedestrians or bicyclists and shall give any audible signal when necessary. -

Txdot Railroad Crossing Design Guidelines

THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Railroad Crossing Design Guidelines Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS A. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................A-1 B. ACTIVE DEVICE CONFIGURATIONS................................................................B-1 C. RAILROAD CROSSINGS ADJACENT TO TRAFFIC SIGNALS.....................C-1 D. RAILROAD CROSSING CLOSURES AND CONSOLIDATIONS....................D-1 TxDOT TOC-1 2016 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Railroad Crossing Design Guidelines Introduction A - INTRODUCTION The following design guidelines are intended to assist project designers with roadway design at railroad crossings and supplement the TxDOT Railroad Crossing Detail Standards Sheets (RCD) which contain standards for device placement distances, gate lengths, and crossing panel sizes. These guidelines are not standards, and are intended as examples for various rail-highway configurations. A diagnostic inspection team will determine the ultimate design for each railroad crossing project. The ultimate design shall be compliant with the Texas Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (TMUTCD) and American Railway Engineering and Maintenance-of-Way Association (AREMA) standards. The guidelines are broken down into 3 main categories: ♦ Design of Active Device Configurations ♦ Design of Railroad Crossings Adjacent to Traffic Signals ♦ Design of Railroad Crossing Closures and Consolidations Guidelines are subject to change. TxDOT A-1 2016 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Railroad Crossing Design Guidelines Active Device Configurations B - ACTIVE DEVICE CONFIGURATIONS LEGEND Cantilever Gate Assembly I-13 (9”x15”) Mast Flasher R15-1 48"X9" ACTIVE DEVICES NOTES R15-2P 1. EMERGENCY NOTIFICATION (I-13), one sign installed 27"X18" with active device on each approach to the crossing. 2. Gate distance above ground when lowered measured from bottom of gate to top of mast foundation. -

Access Management in the Vicinity of Intersections

Technical Summary Access Management in the Vicinity of Intersections FHWA-SA-10-002 Foreword This technical summary is designed as a reference for State and local transportation officials, Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) Division Safety Engineers, and other professionals involved in the design, selection, and implementation of access management near traditional intersections (e.g., signalized, unsignalized and stop controlled intersections). Its purpose is to provide an overview of safety considerations in the design, implementation, and management of driveways near traditional intersections in urban, suburban, and rural environments where design considerations can vary as a function of land uses, travel speeds, volumes of traffic by mode (e.g., car, pedestrian, or bicycle), and many other variables. The technical summary does not include any discussion on roundabout intersections. More information about roundabouts is available in Roundabouts: An Informational Guide, published by the FHWA [1]. Section 1 of this technical summary presents an overview of access management factors that should be considered for improving safety near intersections in any setting. Section 2 presents access management considerations and treatments to improve safety near traditional intersections in suburban, urban, and rural settings. This section features a case study of an access management retrofit project in a suburban area. Section 3 points the reader to additional resources. This publication does not supersede any publication; and is a Final version. Disclaimer and Quality Assurance Statement Notice This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The U.S. Government assumes no liability for the use of the information contained in this document. -

Chart of Moving Violations

CHART OF MOVING VIOLATIONS The following chart lists the moving violations that are designated by the Texas Department of Public Safety pursuant to statutory authority. The violations listed are subject to assessment of points under the Driver Responsibility Program contained in Subchapter B, Chapter 708, Texas Transportation Code. Not all of these violations apply to Habitual Violator action under § 521.292(a)(3), Transportation Code. EFFECTIVE June 22, 2004 Driver Arrest Title* Responsibility Points Aggravated assault with motor vehicle Yes ALR CMV .04 - ADM No ALR CMV HZMT .04 - ADM No ALR-CMV HZMT REF-ADM No ALR-CMV REFUSAL-ADM No Backed up on shoulder (or roadway) of controlled access highway Yes Bus driver failed to activate warning signal/equipment Yes Bus failed to stop at RR crossing Yes Bus shifting gears while crossing RR tracks Yes Changed lane when unsafe Yes Coasting Yes Coasting (truck, truck tractor or bus, specify) with clutch disengaged Yes Consume alcohol while driving Yes Criminal negligent homicide with motor vehicle - 1st or 2nd degree Yes Crossed RR with heavy equipment without notice Yes Crossed RR with heavy equipment without stop (or safety) Yes Crossing fire hose without permission Yes Crossing physical barrier Yes Cut across driveway to make turn Yes Cut corner left turn Yes Cut in after passing Yes Did not use designated lane or direction Yes Disregard solid green turn signal arrow Yes Disregarded flashing red signal (at stop sign, etc.) Yes Disregarded flashing yellow signal Yes Disregarded lane control signal -

Intersection Geometric Design

Intersection Geometric Design Course No: C04-033 Credit: 4 PDH Gregory J. Taylor, P.E. Continuing Education and Development, Inc. 22 Stonewall Court Woodcliff Lake, NJ 07677 P: (877) 322-5800 [email protected] Intersection Geometric Design INTRODUCTION This course summarizes and highlights the geometric design process for modern roadway intersections. The contents of this document are intended to serve as guidance and not as an absolute standard or rule. When you complete this course, you should be familiar with the general guidelines for at-grade intersection design. The course objective is to give engineers and designers an in-depth look at the principles to be considered when selecting and designing intersections. Subjects include: 1. General design considerations – function, objectives, capacity 2. Alignment and profile 3. Sight distance – sight triangles, skew 4. Turning roadways – channelization, islands, superelevation 5. Auxiliary lanes 6. Median openings – control radii, lengths, skew 7. Left turns and U-turns 8. Roundabouts 9. Miscellaneous considerations – pedestrians, traffic control, frontage roads 10. Railroad crossings – alignments, sight distance For this course, Chapter 9 of A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets (also known as the “Green Book”) published by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) will be used primarily for fundamental geometric design principles. This text is considered to be the primary guidance for U.S. roadway geometric design. Copyright 2015 Gregory J. Taylor, P.E. Page 2 of 56 Intersection Geometric Design This document is intended to explain some principles of good roadway design and show the potential trade-offs that the designer may have to face in a variety of situations, including cost of construction, maintenance requirements, compatibility with adjacent land uses, operational and safety impacts, environmental sensitivity, and compatibility with infrastructure needs. -

How to Drive Near Trains Approximate Facilitation Time: 20-30 Minutes

How to Drive Near Trains Approximate facilitation time: 20-30 minutes Materials ● How to Drive Safely Near Trains Video ● Test Your Train Safety Savvy Worksheets - enough copies for all students (& Master for your reference) ● Rail Safety Scenarios Master document for your reference Learning Objectives At the conclusion of the lesson, the learner/student will be able to: ● Identify the names and meanings of signs and signals around railroad tracks: ● Explain how to safely drive across train tracks ● Describe why not to walk near or on railroad tracks ● Explain how to safely drive around light rail FLOW Introduction Begin with a brief class reflection about students’ personal experience with trains and railroad crossings: ● Are there any train tracks you cross regularly? Where? Picture this in your mind’s eye: What do you notice? What signage is present? What is different about crossing a railroad track from crossing another street at an automotive intersection? What is similar? Watch Video How to Drive Near Trains [10:53] Ask the class to reflect on what information in the video really stood out for them and/or they found surprising. Student Worksheet: Test Your Train Safety Savvy Have students complete the worksheet, Test Your Train Safety Savvy, then review the correct answers as a class, using the Test Your Train Safety Savvy Master. Scenarios (Optional Extension) If time allows, you may wish to discuss one or more of the scenarios from The Rail Safety Scenarios Master as a class. Test Your Train Safety Savvy - MASTER 1. At which of the following signs should you Yield? a) Crossbuck b) Crossbuck w/Yield c) Crossbuck w/Stop Answer: a + b. -

Superstreets SUPERSTREETS

System Modification Geometric Design Superstreets SUPERSTREETS Description A "superstreet" has intersections in which the minor cross-street traffic is prohibited from going straight through or left at a divided highway intersection. The minor cross street traffic must turn right but can then access a U- turn located in the median to proceed in the desired direction. Doing this reduces the number of traffic signal phases required to move traffic through the intersection thereby allowing for longer green times on the major roadway and Alamo RMA thus reducing congestion caused by the signals. Superstreets are best for an arterial intersection Cost: with a low-volume cross-street and a need to Time: Moderate maintain large throughputs on the major road. Impact: Corridor Target Market Who: State & Local Arterials with Heavy Delays at Intersection Hurdles: Right-of-Way, Signalized intersections commonly cause major Public Acceptance delays and congestion on corridors due to the time required for each phase. The delays can be . Superstreets can reduce delay, improve reduced if multiple phases run at the same time traffic flow, and simplify signal timing at and the through traffic on the minor street is the main intersection. Eliminating left redirected. turns and allowing multiple signal phases can simplify and improve the Arterial Intersections with Large Left Turn intersection. Volumes Left turns are a cause of major delay, as they . Superstreets can maintain existing interfere with opposing traffic and can also commercial access. The superstreet require their own signal at certain intersections. concept can work well with existing Congestion can be reduced if the left-turn access management plans to allow easy movements are removed from the main access to commercial areas, limiting the intersection and are made at a location away traffic effects on local businesses and from that area.